The Astadhyayi of Panini (A Brief Exposition)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAJ958 |

| Author: | J.A. F. Roodbergen |

| Publisher: | Vaidika Samshodhana Mandala, Pune |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| Pages: | 88 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 220 gm |

Book Description

Foreword

The Vaidika Samshodhana Mandala (Adarsh Sanskrit Shodha Samstha), Pune feels proud in announcing the publication of this scholarly work, 'THE ASTADHYAYI OF PANINI A BRIEF EXPOSITION' by J. A. F. ROODBERGEN, University of Amsterdam (retd). We are very much sure that this work will receive a warm welcome from scholars, researchers and students of grammar in general and of Panini ill particular:

The volumes of the 'THE ASTADHYAYI OF PANINI' jointly edited by Prof. Dr. S. D. Joshi and J.A.F. Roodbergen were published by the Sahitya Academi, one volume on P.4.l.1 - P. 4.1.75 was published by us last year.

These volumes no doubt deal with the Astadhyayi very elaborately, thoroughly. Despite of this scholarly treatment there remain need of such compact work to know what Panini is, this work exposes the methodology of this brilliant grammarian. The integrated approach of the author helps to understand clearly the structure of the Astadhyayi. We specially acknowledge the sumptuous donation we received for the publication of this book. The donoris sincere lover and serious scholar of Panini.

We sincerely express our deep sense of gratitude towards the authorities of The Rashtriya Samskrit Samsthan, New Delhi for substantially funding the entire scheme of Adarsha Sanskrit Shodha Samstha. I sincerely thank Prof. Dr. S.D. Joshi who despite of his ill health solved my difficulties and clarified the doubts while finalizing the press draft.

We are grateful to Ms. Aditi Pandit for prompt and perfect typesetting. Our sincere thanks are also due to Mr. Rahul Marulkar of Mandar Printers, Pune for speedy printing.

Preface

The initial idea conceived in 2011 was to write a small-size book on Panini's Astadhyayi, like a pocket- book, which could serve as a short introduction for an interested non-specialist, non-linguist reader. So the question was, with that in view, what to include and what to leave out from the mass of technical information required for understanding. A selection of bare essentials has been made. But whether that will satisfy or even interest a non-specialist, non-linguist reader remains doubtful, because of the technicalities still involved in explaining and understanding. So what resulted is a short work of which it is hoped that it will be useful as a vade mecum for specialists, a linguist or student of Sanskrit in that branch of science which is called vyakarana in India.

I express my thanks to Dr. S. D. Joshi for many helpful suggestions.

I thank Dr. Mrs. Bhagyalata Pataskar, Director of (Vaidika Samshodhana Mandala (Adarsh Sanskrit Shodha Samstha.), for assistance in proof-reading. She also has suggested improvements in the text of the work which I have gratefully accepted.

Introduction

1. Language and speech

Language is a separate domain, aspect, of human experience, constituted by rules of its own, not reducible to those of other domains of human experience, like the ones studied by psychology, logic, history or sociology. Language cannot be subsumed under behaviour or communication, because these are unspecified concepts and need to be specified again by language. Language manifests itself originally in speech by which the totality, of individual speech-acts is meant. Speech presupposes a human speaker and a listener, and takes place with the help of speech-sounds which are intelligible for other. These sounds are typically different from other sounds, like the blowing of conches, or the sounding of horns.

In speech we talk about things, anything, including the notions we have of things and language itself. In talking about things we refer to those things in the manner of language by using words and structured complexes of words as signs for what we speak about. Signs have meaning in the sense that they stand for the things they signify, the things-meant. To convey meaning by means of words is the essence of language. Signs are different from signals, because the latter depend on previously made, ad hoc conventions for their meaning. Otherwise they cannot be understood. Words used in ordinary, daily, non-technical language do not depend on previously made ad hoc conventions in order to be understood. They are freely usable by any speaker, and they can be understood without a previously made convention (samketa) regarding their meaning.

Words are identifiable by their order of phonemes. Change the order, and a different word results, or a non-word. Being units of sound and meaning, words can independently signify. In that respect a word differs both from its elements and from a word-group 'or an utterance consisting of more than one word. Words also convey meaning, but not all words convey meaning in the same way, depending on the category to which they belong. A broad division may be made between lexical and non-lexical, functional meaning. Use of both meanings is made both for purposes of word-analysis and for the syntactic construction of word-groups and utterances. In the case of lexical meaning 'an: important distinction is made between "literal" and "non-literal, figurative, metaphorical" meaning, in Sanskrit known as abhidhai and laksana respectively.

The unit of speech is the utterance. Its written equivalent is the sentence. An utterance is marked by intonation. Its end is marked by a change of intonation. Thereby also the beginning of a new utterance is known. For Sanskrit the end of an utterance is defined as avasana or virama, that is, a noticed pause in the flow of speech. Thereby also the beginning of a new utterance is known.

Languages are theoretically grouped into families, according to shared distinctive characteristics. One of those languages is Sanskrit. It belongs to a big family, called Indo-European languages. Within this family a smaller group is distinguished, called Indo-Iranian languages. Within this group a still smaller group is known as the Indo-Aryan languages.

The name "Aryan" is derived from the Sanskrit word arya noble which is the accepted self-designation of a conglomerate of nomad clans coming from Central Asia, territories around and between the Caspian Sea and Lake Aral. Looking for pasture lands they moved along the basin of the Oxus river (Amu Darya) and through what is now Afghanistan. They initially settled in the north-west of the sub-continent India, presumably in the first half of the second millennium B.C. From there they moved on further eastward and southward.

Within the Indo-Aryan group a division is made according to a largely presumed age of oral literature. A precise chronology is not possible for lack of early written data. The division is into Old, Middle and New Indo-Aryan. The most archaic Old Indo-Aryan is that of the Vedic Samhitas. Sanskrit also belongs to Old Indo- Aryan, but represents a younger phase, marked by shifts in morphology and vocabulary. Both the Vedic language and Sanskrit are marked by a pitch accent, a rising tone, a falling tone and a combination of both. Middle Indo- Aryan includes the language of inscriptions from the third century B. C. It also includes languages attested in literature and related to Sanskrit. These languages are called Prakrits. The name "Prakrit is derived from the word prakrti ‘origin nature’, and refers to a current form of spoken language used among commoners. It is from these Prakrits that in course of time, noticeable in inscriptions since roughly 1000 A. D., the New Indo- Aryan languages have developed. I mention only Hindi, Bengali, Gujarati and Marathi.

Sanskrit is an inflected language, like Greek and Latin. It has three genders, eight cases, including the vocative. Adjectives are inflected to show agreement with substantives. Verbs are inflected for person, number, tense, mood and voice.

2. The name "Sanskrit"

The name is derived from the (Sanskrit) word sanskrit which means 'polished, that to which· an extra quality is added'. The name is given to that Old Indo-Aryan language which has been analysed in minute detail and codified by Panini. According to Patanjali, a later grammarian, to speak Sanskrit correctly one should listen to the sistas, the learned ones, that is, the grammarians, who live in Aryavarta, literally, the area in which the aryas move about. This is the territory geographically defined as located between the seas at the east-and west-side of the sub- continent, and from the Himalayas to the Vindhyas.

For the language he has analysed in minute detail and then prescribed as standard Panini uses the term bhasa. As the name says, reference is to a spoken language, but spoken by whom? Bhasa is used in distinction from chandas, the language of the Vedic Samhitas and of ritual, but it may also have been used in opposition to what later, become known as Prakrit, the language used in the bazaar, and probably also in homely conversation, by non-learned people. Thus a social, distinction is introduced, according to which Panini declared some" forms to be correct and other forms to be incorrect, non-standard. The name Samskrta first appears as samskrta vak 'the polished 'language' in literature in the Ramayana,(5.2.28), one of the two great Indian epics.

Panini, notes some regional differences indicated : by the genitive words udicam 'of the northerners', and pracam 'of the easterners'. The word dese 'in the region' is to be supplied. The total number of rules in which these words are used is 27 only. Panini is short on theory, but great on grammatical detail. A coherent linguistic theory can only be inferred on the basis of his detailed observations of linguistic data put forth in the form of sutras. The starting point of Panini's analysis is not meaning, or the intention of the speaker, but word-form, as shown in the initial stages of the prakriya.

3. Sanskrit literature

The language used in the epics, the Mahabarata and the Ramayana, deviates from the language standardized by Panini in a number of points. Deviations are noted in practically all parts of grammar, from sandhi to syntax. Classical Sanskrit is the language of poetry, drama, collections of tales -(Pancatantra, Hitopadesa, Kathasaritsagara) and numerous technical treatises in different fields of scholarship (e.g., grammar, ritual, prosody, law, ethics, philosophy, medicine, music.' sculpture, architecture, and commentaries on such works). In short, classical Sanskrit was the language in which the culture of the subcontinent India was expressed, and has been so for a period from roughly about 400 B.C. to far in the nineteenth century. The first recorded appearance of Sanskrit in writing is the Rudravarman inscription from Junagarh, dated around 150 A.D.

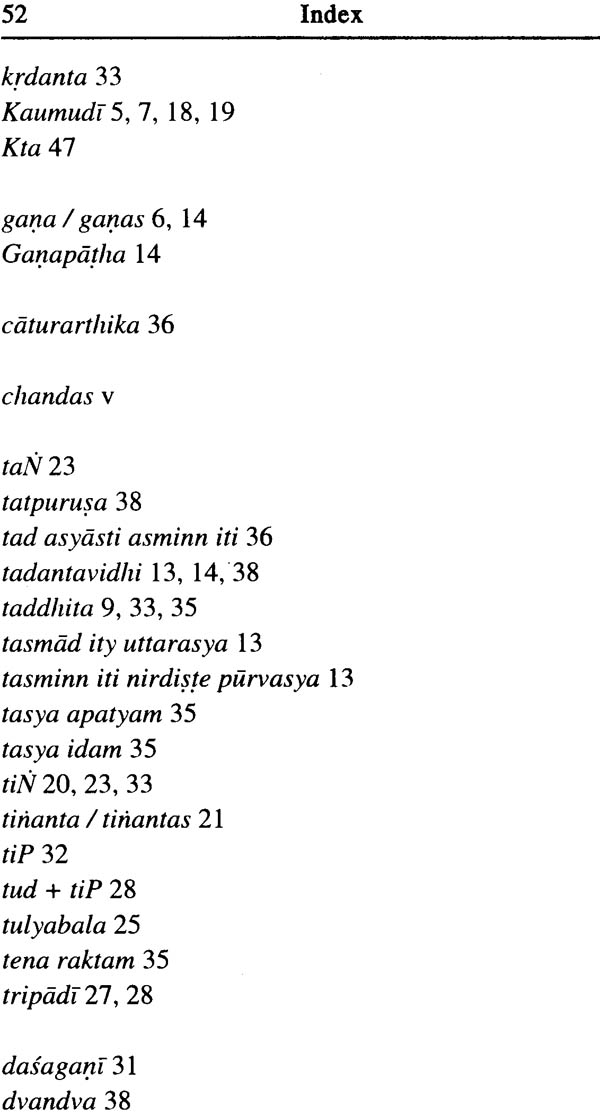

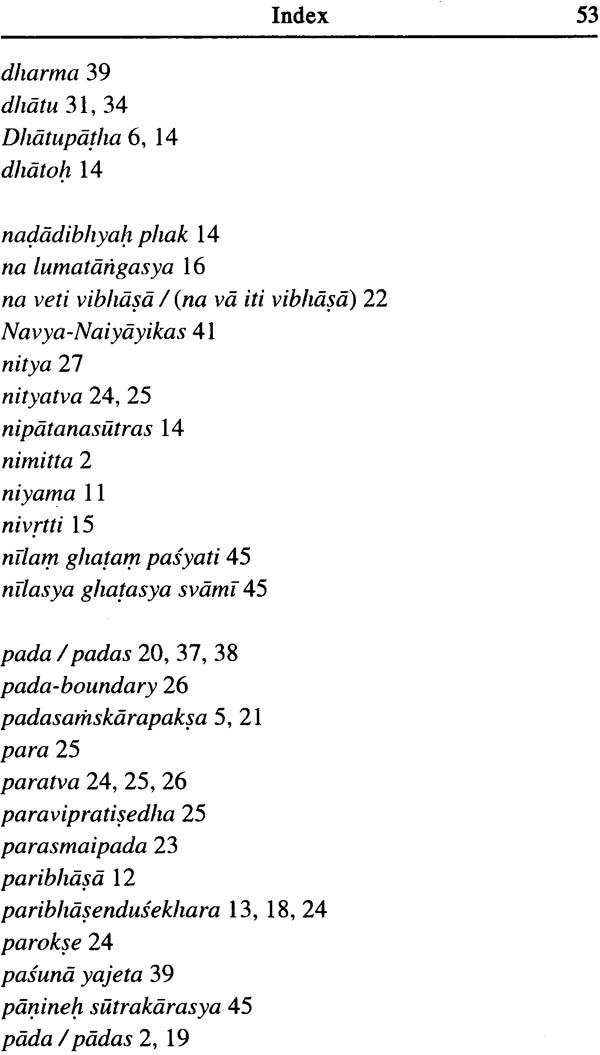

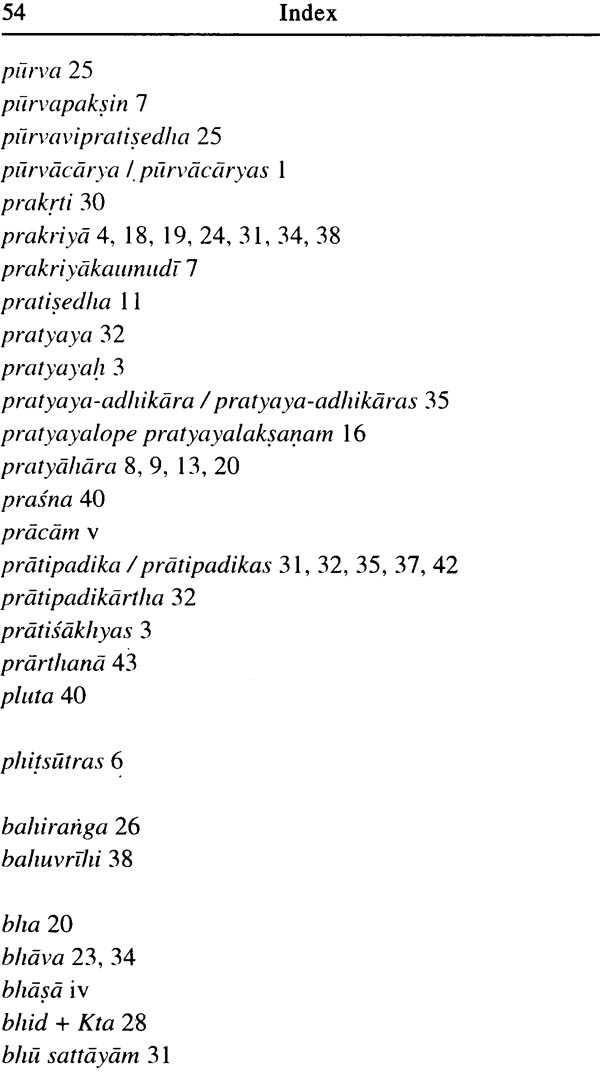

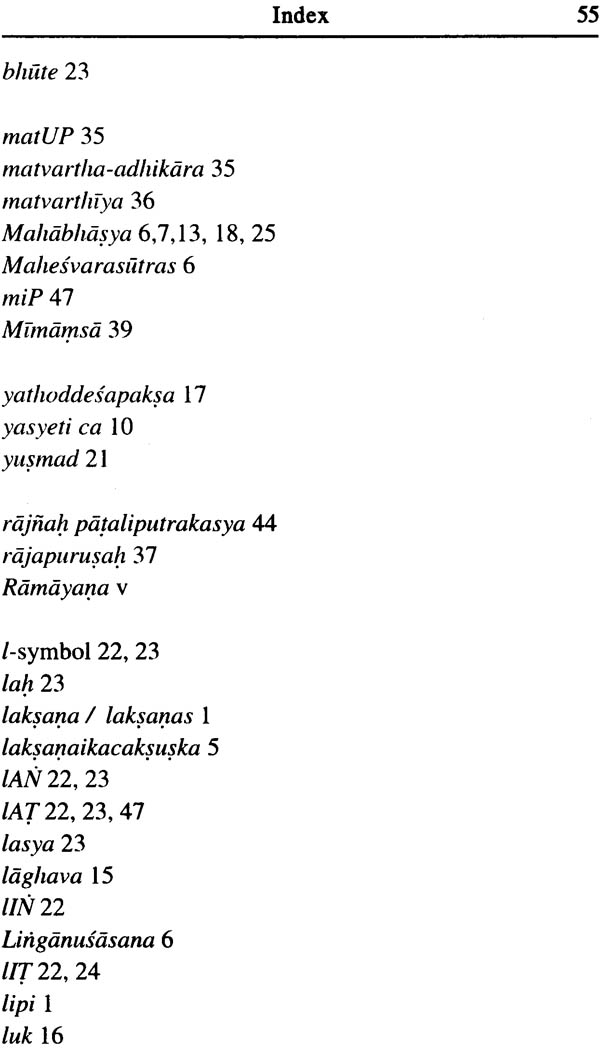

Contents

| | Foreword | |

| | Preface | |

| | Bibliography | |

| | Abbreviations | |

| | Introduction | I-VI |

| | The Astadhyayi | 1- 48 |

| | Index | 49- 58 |

| 1. | The author | 1 |

| 2. | The name of the work | 1 |

| 3. | The composition of the A. | 2 |

| 4. | The character of the A. | 3 |

| 5. | Prakriya | 4 |

| 6. | Texts directly associated | 6 |

| 7. | A supplement, commentaries | 6 |

| 8. | The vocabulary of the sutras : | |

| | Technical and non-technical | 8 |

| 8.1 | The technical (krtrima) vocabulary | 8 |

| 8.2 | The non-technical (laukika) Vocabulary | 9 |

| 9. | The division into separate sutras : | |

| | The function of the particle ca | 10 |

| 10. | Types of rules | 11 |

| 11. | The Ganapatha | 14 |

| 12. | The interpretation of sutras : Anuvrtti and nivrtti | 15 |

| 13. | The notion of option (vikalpa) | 15 |

| 14. | Deletion | 16 |

| 15. | Substitution | 17 |

| 16. | Two methods for studying the A. | 17 |

| 17. | The ordering of sutras | 19 |

| 18. | Boundaries | 19 |

| 19. | The definition of pada | 20 |

| 20. | Sabda and the use of iti in the A. | 22 |

| 21. | The symbol/in the A. | 22 |

| 22. | The order of rule-application | 24 |

| 22.1 | Conflict of designations and rules | 24 |

| 22.1.1 | Conflict of designations | 25 |

| 22.1.2 | Conflict of rules | |

| | Antarangatva and nityatva | 25 |

| 22.2.1.1 | The siddha-asiddha ordering of rule-application | 27 |

| 22.3 | Apavadatva as an all-compassing conflict-solving principle | 29 |

| 23. | Samdhi | 29 |

| 24. | Word-form analysis: Stem and suffix | 30 |

| 24.1 | Stem | 31 |

| 24.1.1 | Dhatu 'verbal base' | 31 |

| 24.1.2 | Pratipadika | 32 |

| 24.1.3 | Anga | 3 2 |

| 25. | Suffix | 33 |

| 25.1 | Krt | 33 |

| 25.2 | tiN | 34 |

| 25.3 | suP | 34 |

| 25.4 | Taddhita-suffixes | 35 |

| 25.5 | Stripratyayas | 37 |

| 26. | Compound – formation | 37 |

| 27. | Vakya | 39 |

| 27.1 | Syntactic relationships | 41 |

| 27.1.1 | Karaka | 42 |

| 27.1.2 | The genitive relationship | 43 |

| 27.1.3 | Samanadikarana | 44 |

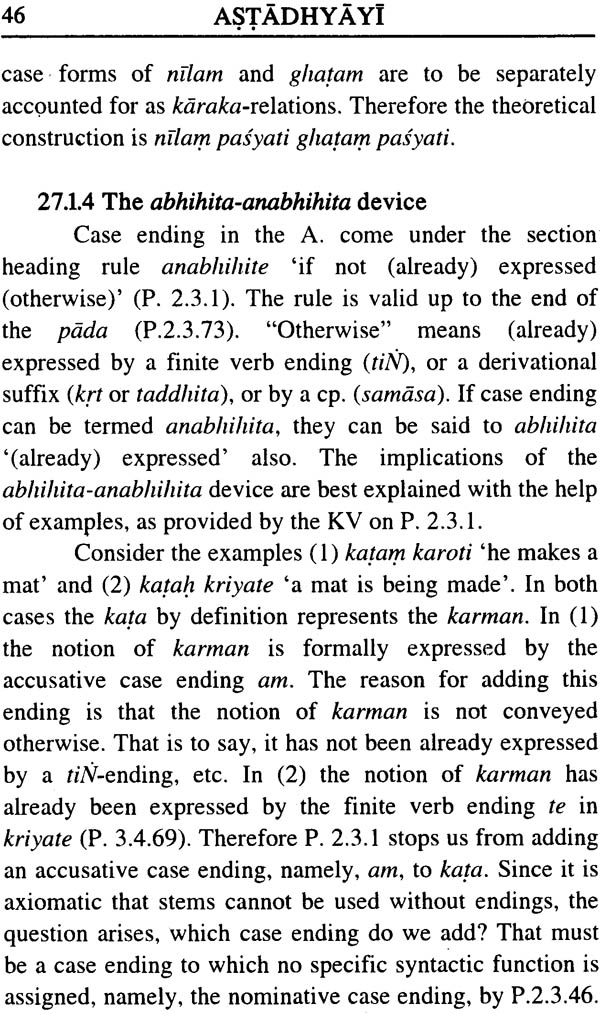

| 27.1.4 | The abhilata-anabhihita device | 46 |

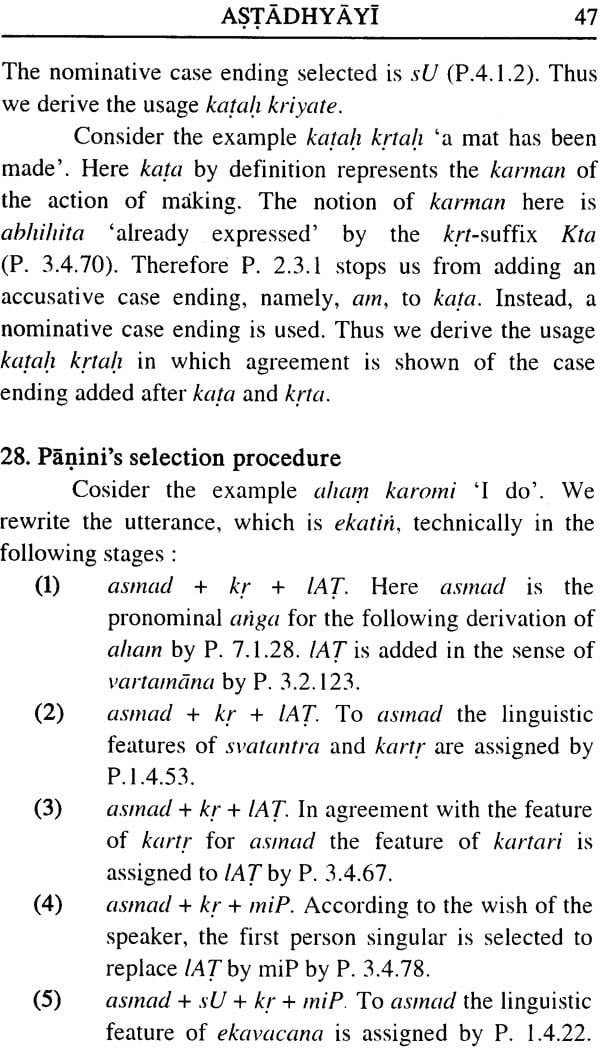

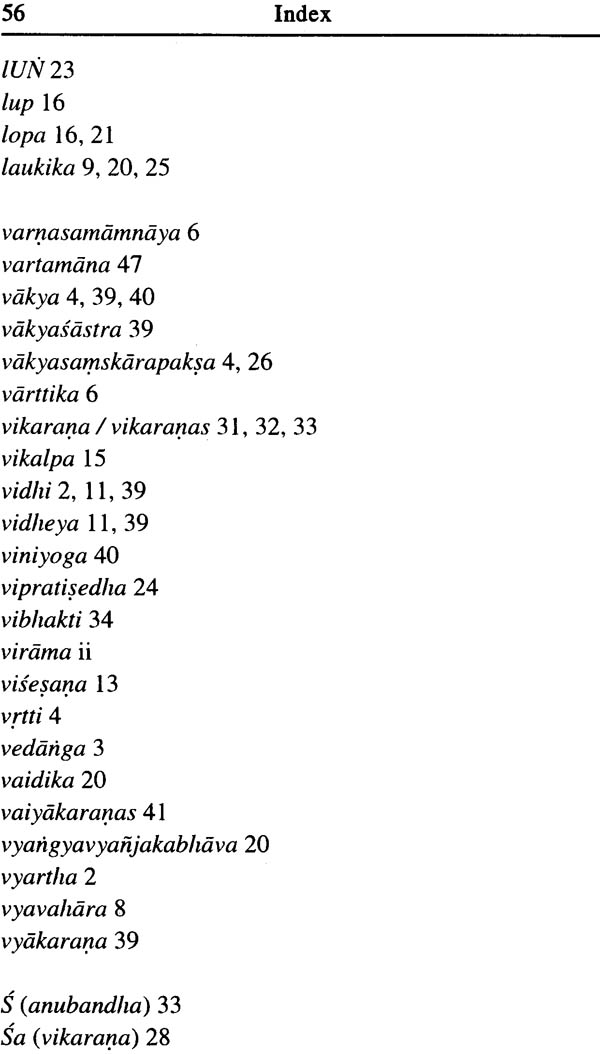

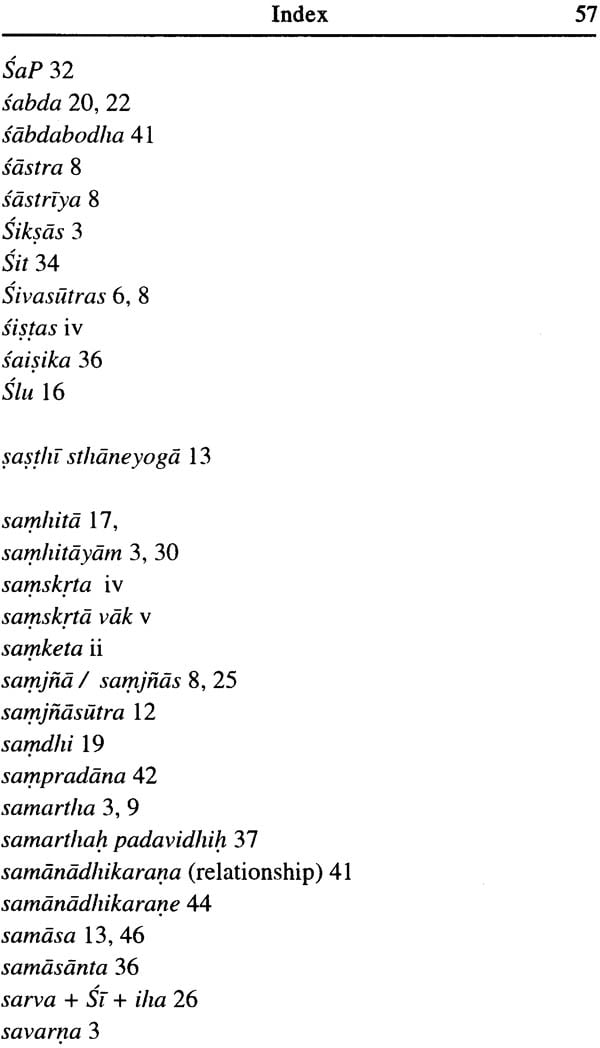

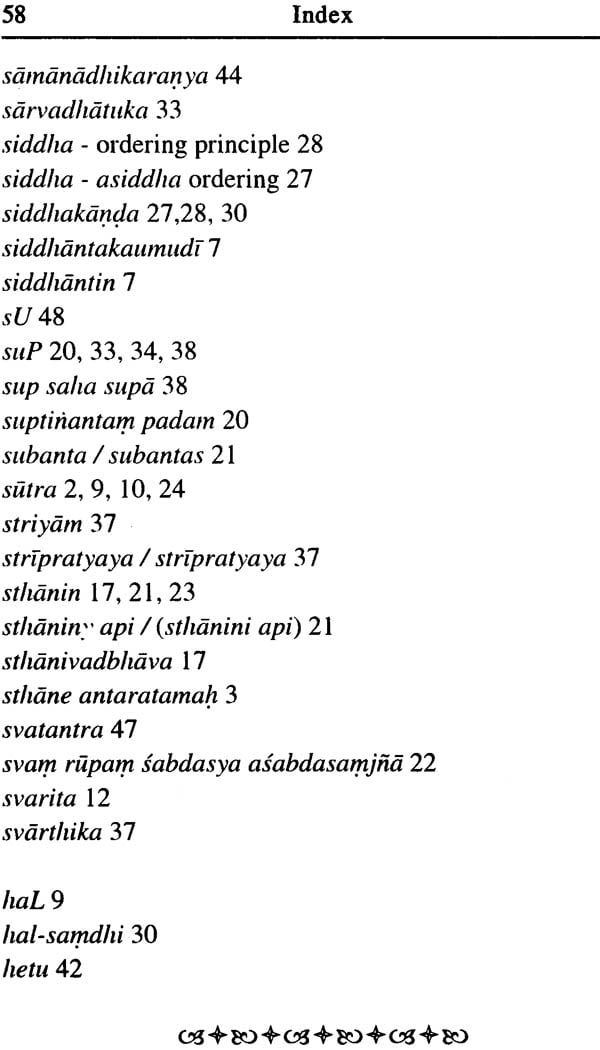

| 28. | Panini' s selection procedure | 47 |