Chinese Sources of South Asian History in Translation- Data for Study of India-China Relations Through Ages (Vol-II)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAV333 |

| Author: | Haraprasad Ray |

| Publisher: | THE ASIATIC SOCIETY |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2006 |

| Pages: | 148 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 270 gm |

Book Description

This is the second volume of the series Chinese Sources of South Asian History in Translation. Entitled "Chinese Sources on Ancient Indian Geography", it comprises two texts on Historical Geography. The author has translated and annotated exhaustively the latest collated versions of the texts which will help the students of ancient Indian History and Geography in exploring some of the hitherto unexplored domains of ancient India. The first work, Kang Tai's Notices on Foreign Countries during the Wu Dynasty (AD 220-280) is a collated text of all available notices that go in the names of Kang Tai and other envoys and travellers whose writings are no more extant but are scattered in other collectanea. Collected over a number of years they give a coherent idea about the all-sea route passing through the Malacca Straits touching Ge-ying and Jia-na-Tiao (Ganadvipa), and reaching the Eastern and Southern India and may be the Asia Minor (Daqin).

The second work, The Commentary on the Water Classic (5th- 6th cent. A.D.) does not only record the geography of Central Asia, but also acquaints us with profuse information on the countries nearby, and India, Afghanistan and other areas outside China. The author shows knowledge of many Indian cities of North, South and Eastern India, and gives the impression that to the Chinese the entire Indian continent constituted one geographical and political concept.

Both the works are important additions to the libraries of bibliophiles and will prove to be sine qua non for the Indian orientalists researching for data on our past.

The two texts on historical geography translated in this volume are rare works and were procured with the good wishes and efforts of various friends. The first one, the Kang Tai Wushi Waiguo Zhuan Jizhu, is a collated and annotated version of all available notices that go in the names of Kang Tai and other authors whose writings are no more extant and are available only from other collectanea. These scattered quotations were collected over a long period by the late Professor Xu Yunqiao (Hsu Yunts'iao) and published by the Institute of South-east Asian Studies, Singapore. Professor Xu had also added notes wherever possible. In my translation I have updated them and added additional notes. This work was collected for me by my ex-student Mr. S.R. Lamba, former Assistant Director of the A.I.R.

As for the second work, the Shuijing Zhu, Professor Geng Yinzeng who used a Qing dynasty edition has omitted in her Collection some of the portions from the chapters on India (j.1 & 2) and the adjoining areas. But I did not think it worthwhile to embark on translation without having before me the entire texts of both the juans. After a long search I could lay hands on the entire work through the efforts of my young friend, Dr. R.K. Rana of the Department of Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi. Dr. Rana procured from Taipei the present rare version, a critical edition collated by the late scholar Mr. Wang Guowei. Although not properly punctuated, this version titled Shuijing Zhu Jiao is important for getting at the correct readings since the editor has given other readings also. L. Petech's Northern India according to the Shuiching-chu has also been of considerable help for explanation of some of the nearly undecipherable expressions.

For a better appreciation of the importance of these two works we have added introductory notes to each of them with their translations.

This volume contains a detailed explanation of the geographical data found in the ancient Chinese texts named Kang Tai Wushi Waiguo Zhuan Jizhu and Suijing Zhu, the first of which was collected and collated from scattered sources by the late Professor Xu Yunqiao and published in Singapore, while the second work, a rare version, was procured from Taipei. Professor Haraprasad Ray, an eminent Sinologist, has made relevant additions to the notes of Professor Xu Yunqiao, and explained many terms used in these two very ancient texts. The work has a Chinese chronology and table of transliteration, which would be useful to the readers. Claudius Ptolemy is venerated as a great astronomer, mathematician, geographer and cartographer of the Roman civilization. The two ancient Chinese texts, mentioned above, make it absolutely evident that in ancient China both geography and, to some extent cartography, were highly developed by inquisitive travellers who, however, did not always mention the difficulties they had to face. This volume would be regarded as a highly significant contribution to the geography of ancient India.

As already explained in the preceding volume (No. 1), my aim under this project is to provide data to the scholars of India-China relations through translation of and annotations to the hitherto known, unknown and little-known records on South Asia in the Chinese writings, mainly historical, and then collating these with the results of studies and archaeological discoveries in India, China, Central Asia and elsewhere. The results of this endeavour will enable the researchers to delve into the political contacts and conflicts, commercial exchanges and cultural intercourse between the countries of this vast area.

With the development of the kingdom and opening up to the outside world through explorations, political contacts and military expeditions, the Chinese gathered extensive knowledge of their neighbours far and near. In one such exploration Zhang Qian the envoy of the Han Emperor Wu (140-87 B.C.) reached the fringe of the then north-west India. At Bactria (Daxia) he heard about India (Shendu). Little did Zhang Qian and his emperor realise that this "hot and humid" country was to influence almost every aspect of Chinese life during the next thousand years or more. Busy traffic across Asia along the Silk Road reached an unprecedented scale. The Han court used to send dozens of missions to the western countries (as the Central and South Asian kingdoms were known to them), and these latter countries like the Roman Orient, Persia (Iran), India, the Arab Empire and those in south-east Asia kept on sending to the Han capital (Luoyang or Changan ) their envoys with the presents of local products.

Knowledge expanded as the Chinese historians and geographers started scouting and surveying their own territory as well as the region beyond and kept on recordings the events and geographical details of the countries seen by their own eyes or heard from the travelers, traders and envoys. Their interest was not only limited to the political, economic and social spheres but also to topography, the mountains the hills and the rivers.

The result was the profusion of writings on China, Central Asia, Persia, Afghanistan, India, as well as the far away Roman Orient on the one hand, and on the other, the emerging kingdoms and the port towns of south-east Asia, and the sea-cum-land and all-sea routes leading to India, Sri Lanka and beyond.

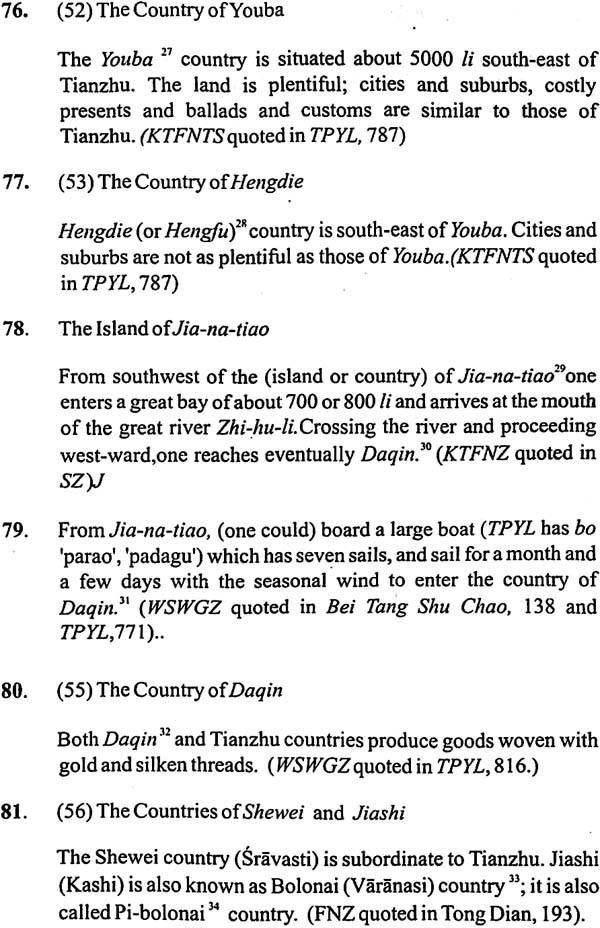

The first of the two works translated here concerns the latter subject and the all-sea route passing via the Malacca straits touching Geying and Jia-na-tiao (Gantavipa?) and reaching both the eastern and southern parts of India and may be the Asia Minor (Daqin). This is what goes in the name of Kang Tai, the official of the Wu Dynasty of the period of Three kingdoms (AD 220-280), who gathered extensive knowledge about India and recorded them. These records are handed down to us only in the various encyclopedias and other collections details of which are given in my introduction to the various compilations that are associated with the name of Kang Tai. Kang Tai's account of the lower Ganga has found place of importance in both the compilations titled Kang Tai Wushi Waiguo Zhuan Jizhu and Shuijing Zhu. Read together with Faxian's account, they shed an interesting sidelight on the 5th century hydrography of Bengal. The Bhagirathi which leaves the Gang a few kilometres below Malda (West Bengal), is responsible for the formation of the Hooghly. It is a river with weak flow now, but in former times its channel was more important than the Padma which now carries the greater part of the waters of the Ganga to the Meghna estuary. For Kang Tai the Bhagirathi was the main channel of the Ganga, since Tamralipti was the port where the Ganga entered the sea. This means that the relative importance of the Bhagirathi and the Padma has been reversed during the last more than 1600 years. In view of the antiquity of our texts roughly dating back to 3'nd century A.D., their significance for the history of the Bengal rivers can not be overlooked.

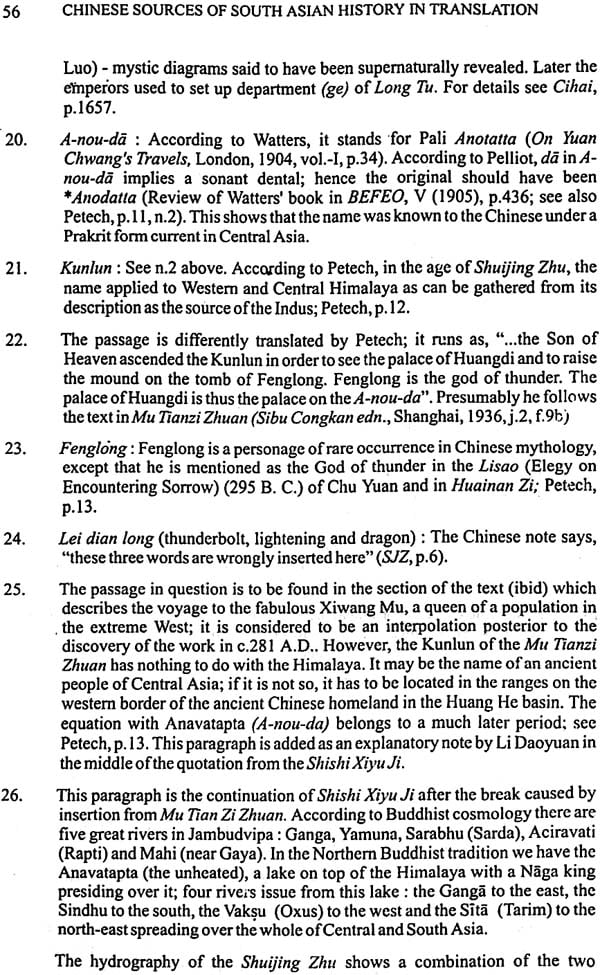

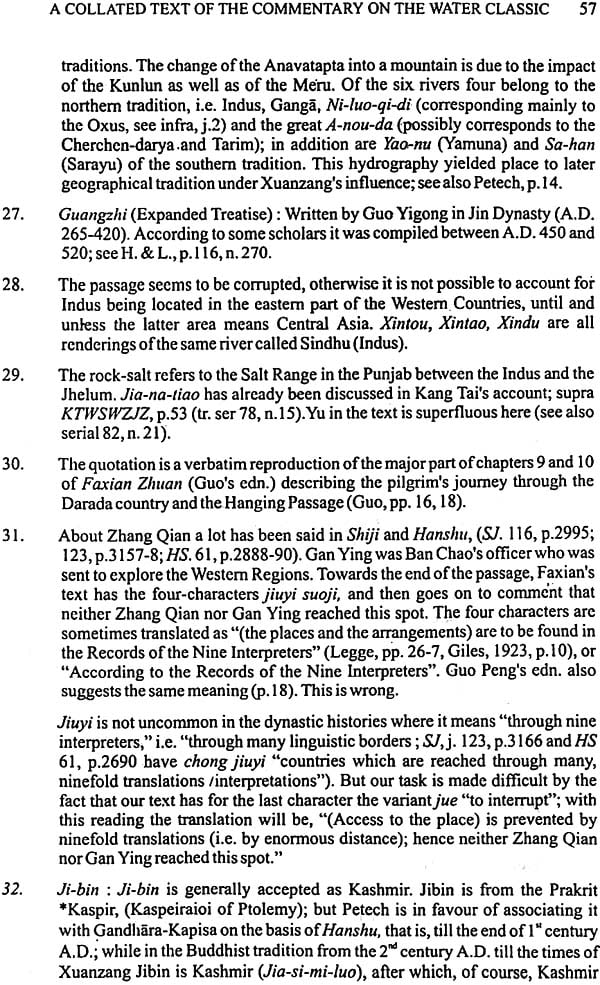

The early centuries of the Christian era are of crucial importance for the history of the Buddhist religion as well as for India-China relations. This period saw the emergence and development of the Mahayana, the effect of which is reflected in the treatment of such a mundane subject as geography. It is necessary to point out that the present treatment of hydrology follows the route of travel trodden by the Buddhist monks like Faxian, and the unidentified Shishi, Zhu Fawei and Fo-tu-tiao.

Shuijing Zhu (SJZ) does not only record the geography of ancient China, it also acquaints us with similar information on the countries nearby, and India, Afghanistan and other areas outside China's territory. The author has sometimes made confused statements like placing Indus (Sindhu) near Mathura; and then making this unique discovery that Madhyades’ a which is identical in its Chinese translation i.e. Zhongguo (Middle Kingdom) is so-called because the food habit and dresses of both these countries are the same; sometimes the bearings are mixed up, as when the Ganga is made to flow north of Vaisali, Saketa and Kapilavastu; on another occasion he chooses to follow the direction of Faxian's travel and thus commits the blunder of making the river flow from the east.

Inspite of these aberrations we must acknowledge it as a source of considerable information. The author of SJZ shows knowledge of many Indian cities, the source for at least half of them being Faxian's travelogue. He mentions the North, the Middle and the South India, an indication that to the Chinese the entire continent constitutes one geographical and political concept. Mathura, Kashmir, Bhera (in Punjab), Gandhara, Sarikol (south of Yarkand), Uddiyana (Wuchang), Kusinagara, Vaisali, Sankisa (in Farukhabad district), Saket (Faizabad, U.P.), Kapilavastu (Nepal), the kingdom of Bimbisara i.e. Rajagrha, Ramagrama (between Magadha and Vriji),Magadha, Kasi (Benaras), Campa (Bhagalpur), Pataliputra (Patna), Puli of the Pali texts (below Campa on the lower Ganga), Tamralipti, , Taksasila, Peshawar and Sri Lanka, all these places find mention here. The author acquaints us with the names and quotations of the now lost works like Waiguoshi, Shishi Xiyu Ji and such writers as Zhu Fawei and Fo-tu-tiao.

The work quotes profusely from the ancient texts that provide us with information on the flora and fauna of India of which mention may be made of Barassus flabellifera (of which bhurja-patra is made), Eugenia jambolana (jambu), Saraca indica (asoka), Vitex Negundo (nyagrodha), Santalum album (sandalwood), Shorea robusta (sala), and so on. Among the fauna 'short stepping' horse of Central Asia, the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) and the vulture of the Grdhrakuta fame, etc. merit mention.

Like Faxian, Li Daoyuan ignores political matters of India and the description of the topography is based entirely on the previous authors, Faxian being the latest, and in this respect the work offers itself as a compilation that incorporates data prior to the fifth century A.D. and offers us the hydrography of India linking it to its Central Asian nexus, albeit largely fictitious.

Both of these works are important in their own way, the first one introducing the readers to the maritime Silk Route, while the SJZ like SJ and HS, leading us over the Pamirs to the Central Asian Land Route, the main Silk Route. SJZ also cites quotations which may help locate the 'penance' tree, the Grdhrakuta hill and some other unidentified sites.

In fine, one can not fail to notice between the lines of the Commentary on the Water Classic (SJZ) deep Chinese devotion towards everything related to the Buddha and Buddhism, more of which will be found in the volume that follows.

**Contents and Sample Pages**