English and Sanskrit: An Interface

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAJ228 |

| Author: | Harekrishna Satapathy |

| Publisher: | Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha, Tirupati |

| Language: | Sanskrit Text with English Translation |

| Edition: | 2011 |

| Pages: | 142 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 200 gm |

Book Description

Foreword

It is significant to note that the English department of the Vidyapeetha has achieved the task of publishing yet another book, wherein the articles presented in the second seminar conducted in the Vidyapeetha are included.

In the present context of globalisation, the need for studying the multiple aspects of a language as also the comparative natures of various literatures has been on the rise. This speaks of the usefulness of publication of the present volume titled “English and Sanskrit: An Interface”.

Through the courses of study in the Vidyapeetha as well as through the conduct of seminars, it has become possible for the faculty in the department to delve into the deep ocean of English-Sanskrit studies.

More that 10 scholarly papers on comparative themes are being included in this volume which indicate to the range of English-Sanskrit studies. This book reflects the avowed aim to contemporise Sanskrit studies in relation to a modern language like English.

I appreciate Dr. V. Sujatha and Dr. R. Deepta for the attempts made in this direction and wish the department would see many more such activities.

Preface

“No man is an island” goes the famous saying. With ever increasing globalization, it is becoming more and more emphatic that no sphere of human activity let alone literary activity can remain untouched by others. Hence the importance of comparative studies in the present day world. Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha has always been encouraging any attempt made in that direction for which the publication of “Bridging English- Sanskrit Literatures” (the earlier book) stands a testimony. In its exploration into the wide area of comparative studies, the Department of English in the Vidyapeetha conducted a seminar on 30th & 3Pt, January, 2009.

The proceedings of the seminar have taken the shape of a book. The papers included in the book suggest the length and breadth of the comparative studies possible between Sanskrit and English studies.

P.M. Nayak’s “The Indivisible Aesthetic Triad” is an essay in comparative aesthetics. Western critical system dates back to the days of Plato and Aristotle. On the English side, we have a continuous tradition from Sir Phi lip Sidney onwards. The Indian aesthetic system too has a hoary past and a continuous history from the Rigveda down to the contemporary times. Our aestheticians have theorized on the three constituents of literary creation: the author, the audience and art. To quote a short passage from Nayak’s learned paper:

The individual has never been important in Indian thought. Perhaps, therefore, tragedy has never developed in India as it has in the west. The basis of tragedy, which is a dichotomy between man and God, never existed in India. Man here has been a part of the supreme Reality. Individual feelings were always suspect in the eyes of Indian theories ... In Indian aesthetics the ultimate aim of art has always been viewed as the production of bliss or anandam through universalisation ... Thus art has an ontological status, no physical existence.

V. Rangan’s paper “A Note on Lokadharmi and Natyadharmi : Two Practices” is an exemplary paper on the two uses of language in Sanskrit literary compositions. Lokadharmi is usually translated as ‘realism’ and Natyadarmi as ‘artism’. But the English equivalents do not do fully justice to the implications involved in original terms. A play that is simple in plot construction, dealing with characters who exhibit a natural behaviour speaking a language that is commonly spoken by men and women in everyday life belongs to the Lokadarmi type. But the Natyadarmi type involves complex plot construction with multiple layers employing figurative language and poetic diction. Rangan’s learned paper abounds in examples drawn from Shakespeare, Synge, Shaw and other writers from a very wide range of English literature.

S. Ramaswamy’s paper “Kalldasa’s ‘Ritusamharam’ and the ‘Seasons’ in English Poetry” was a veritable literary treat. He took up for a comparative study Kalidasa’s well- known Ritusamharam and ‘Seasons’ in English poetry. Passages from Thomson’s ‘Seasons’, Collins’ “Ode to Evening”, Shelley’s “Summer and Winter”, Keats’ “Ode to Autumn” were subjected to a close scrutiny to prove that there has been a close affinity in the handling of the theme of the seasons in the two traditions, Sanskrit and English.

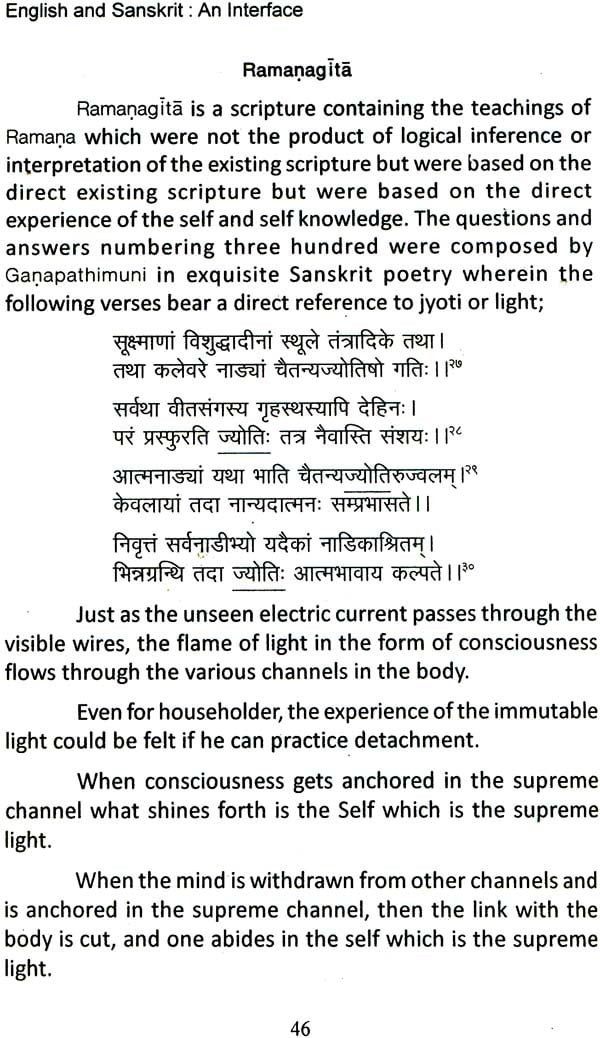

The term ‘light’ is a loaded term, implying several meaning in any culture, it can be a symbol, a metaphor, an archetype. Ranganath explores this term in his paper ‘Light’ in the Light of English and Sanskrit Sources” and shows how this term has been conceptualized by Sanskrit and English poets. Shri Aurobindo, Cardinal Newman, Rabindranath Tagore, Edwin Arnold, among the English and a whole lot of Sanskrit compositions starting from the Vedas, Upanishads, Brahma sutras are the primary sources from which analogies were drawn. The paper elicited a great deal of response from the enthusiastic audience.

Narasimha Rao’s paper “Svabhavokti in English Poetry” was an eye-opener in many respects. Most students and scholars in the domain of English studies had heard of the term ‘vakrokti’ and this was seen in relation to the New critical concepts, irony, ambiguity, paradox, etc. The term ‘vakrokti’ denoted deviant language and hence it was understood as a qualitative term in the context of interpreting texts along the lines suggested by Cleanth Brooks and William Empson. But the term ‘svabhavokti that connotes natural language bereft of any linguistic deviance is equally capable of arousing profound emotions. Poets such as Word worth, Hardy, Auden and Philip Larkin have been followers of this tradition of what might be called ‘the poetry of statements’. “All good poetry is not oblique. Even a natural expression is suitable for good poetry, if it gives an aesthetically satisfying meaning”. Narasimha Rao drew plenty of illustrations from chosen English poets to drive home the meaning of the Sanskrit critical term ‘svabbovokti’.

Myth is supposed to be the greatest falsehood that tells you the greatest truth. A great part of literature be it in poetry or fiction, owes its greatness to the employment of the myth. The incorporation of a simple myth often transforms an otherwise sensational, realistic work to a piece of good art. This is proved in Hari Prasanna’s paper “Creative use of the Myth in R.K. Narayan’s The Man-Eater of Malgudi”. Narayan, in his Columbia University lecture, delivered in 1972 said:

“At some point of one’s writing career one takes a fresh look at the so-called myths and legends and finds a new meaning in them. After writing a number of novels and short stories based on the society around me, some years ago I suddenly came across a theme which struck me as an excellent piece of mythology in modern dress. It was published under the title The Man-Eater of Malgudi. I based this story on a well-known mythical episode, the story of Mohini and Bhasmasura”.

Visakhadatta’s Mudraraksasa, a Sanskrit play comprises a variety of situations to consider it either as a play of political intrigue or political strategy. Dr. V. Sujatha in her paper “Visakhadatta’s Mudraraksasa - a play of political intrigue or a play of political strategy?” delves into the probalities of such situations, analyses them and supposes that the moves of both Canakya and Rakshasa could better be termed political strategy than political intrigue. This conclusion has been arrived at, she feels, because all the moves of both Canakya and Rakshasa are directed towards not gaining personal profit or advantage for the so called intriguer or manipulator but for the welfare of the Kingdom.

The article “Sanskrit Narrative Tradition and Some Indian Novels in English” by Dr. R. Deepta, discusses how some Indian novels in English have very dexterously combined the narrative traditions of the West from which the genre novel has emerged and the long intellectual and creative tradition of Sanskrit which foregrounds the Indian world view. These novels, the article elaborates are marked by the use of accomodative appreciation of such a creative reinvention of the novel form.

The quest for beauty has always been a preoccupation with poets, critics and thinkers of all time and all persuasions. Does beauty lie in the object or in the eyes of the beholder? Some such searching questions have baffled artists all along. Satyanarayana Acharya’s paper “Eastern and Western Thought on Poetic Beauty” raises some of these issues. Sanskrit aestheticians have excelled most others in their complex approach to the validation of the concept of beauty in the domain of arts. Dandin, Bamaha, Anandavardhana, Panditaraj Jagannath among others have defined beauty in various terms. A disinterested pursuit of beauty, for its own sake, is the best reward for man. Did not Keats conclude his well-known ode with these words: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, - that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”.

Anantha’s paper “Kalidasa and Wordsworth” makes a comparative analysis of the two poets’ attitude to nature. For both of them nature is a benign influence on man. The best thing for man would be to live in close harmony with the forces of nature. All plays of Kalidasa show how nature has been a guiding influence and a guiding star for people when they are in need of some supreme force to show them the right path in life. For Wordsworth too, “One impulse from the vernal wood, /May teach you more of man, /Of moral evil and good/Than all the sages can”.

Krisna Misra’s allegorical play Prabodhacandrodaya is rich in its use of symbolism. Devanathan, in his richly dense paper “Para-Ontology in Prabodhacandrodaya” full of philosophic technical terms, analyses the play as emphasizing the victory of viveka over moha and compassion over anger. The theme of the paper is an enquiry into what constitutes the ontological being that we refer to as purusa.

S. Bhuvaneshwari’s paper “Aesthetic Experience in Performing Art : Abhlnava and Hegel : A Comparative Study” is a detailed analysis of two aesthetic systems, one Indian and the other Western. She restricts the discussion of the paper to natya and drama. After explaining the philosophic bases of the two systems, she verily concludes that both aestheticians are unanimous in their faith that art is the right medium to reach out to the metaphysical ultimate. Hegel appropriates his theory based on the dialectical method of the triads, whereas Abhinava employs the basic tenets of the Saiva philosophy to arrive at the absolute. In this sense they may be categorized as Absolutist Aesthetic-Philosophers. “Both Abhinava and Hegel are of the contention that, one who is in tune with action and emotions portrayed, slips into self-forgetfulness, where all dualities resolve, and there is abidance in the non-dual bliss Self”.

Contents

| Foreword - Vice-Chancellor | ||

| Dean’s Comments | ||

| Preface | ||

| 1. | The Indivisible Aesthetic Triad | 1 |

| 2. | A Note on Lokadharmi and Natyadharmi - two Practices in Drama | 9 |

| 3. | Kalidasa’s ‘Ritusamharam’ and the ‘Seasons’ in English poetry | 25 |

| 4. | ‘Light’ in the light of English and Sanskrit Sources | 37 |

| 5. | Svabhavokti in English Poetry | 53 |

| 6. | Creative use of the Myth in R.K. Narayan’s ‘The Man-Eater of Malgudi’ | 61 |

| 7. | Visakhadatta’s Mudraraksasa- a play of political intrigue or a play of political strategy? | 75 |

| 8. | Sanskrit Narrative Tradition and Some Indian Novels in English | 81 |

| 9. | Eastern and Western thought on Poetic Beauty | 89 |

| 10. | Kalidasa and Wordsworth | 97 |

| 11. | Para-Ontology in Prabodhacandrodaya | 105 |

| 12. | Aesthetic Experience in Performing Art: Abhinava and Hegel - A comparative Study | 1I5 |