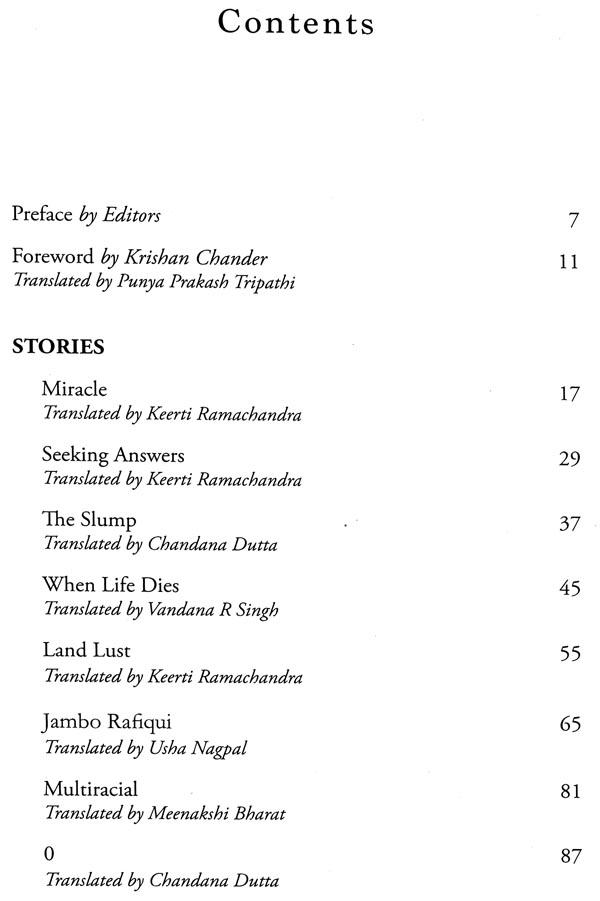

Land Lust ( Short Stories )

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAU191 |

| Author: | Joginder Paul, Sukrita Paul and Vandana R Singh |

| Publisher: | Niyogi Books |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2019 |

| ISBN: | 9789386906809 |

| Pages: | 143 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 300 gm |

Book Description

Evocative and crisp, Joginder Paul's Urdu stories from Dharti ka Kaal are translated into English in Land Lust. His stories offer poignant glimpses of multiracial relations in colonial Kenya and evoke insightful moments of compassion from within harsh xenophobic environs. Paul's characters breathe life into paper and touch readers not just intellectually, but also viscerally. In these stories, we confront Nature and its wildness and see a palpable connection between people and their land. Land Lust attracts empathetic attention to divisive follies of race and colour, and interrogates notions of progress and development. The writer deftly asserts the dignity of black people by including their voices and predicament in these stories.

Joginder Paul

(1925-2016) was born in Sialkot (now in Pakistan). His first story was published in the well-known Urdu journal Saqi in 1945, while his first book of short stories in Urdu, Dharti ka Kaal, was published in 1962. The partition of the country resulted in his migration to Ambala as a refugee. His marriage led to another migration — to Kenya, where he taught English, throughout expressing in his stories the angst of being in exile. Back in India in 1965, he was principal of a college in Aurangabad, Maharashtra, for another fourteen years before coming to settle in Delhi for full-time writing.

Joginder Paul published over thirteen collections of short stories, including Khula, Khodu Baba ka Maqbara and Bastian. Amongst his novels are Ek Boond Lahoo Ki, Nadeed, Paar Pare, and Khwabro. He published four collections of flash fiction (afsaanche), a genre with which he is known to have enriched Urdu fiction significantly. A number of his novels and short stories have been translated into Hindi, English and other languages in India and abroad. His fiction books have been previously published many times in English.

Paul is a recipient of many important literary honours, including the SAARC Lifetime Award, lqbal Samman, Urdu Academy Award, All India Bahadur Shah Zafar Award, Shiromani Award, and Ghalib Award. He was also honoured at Qatar with an international award for contributing to creative writing in Urdu. His fiction has received a lot of critical acclaim, and many Urdu journals in India and Pakistan have published special issues on him. His fiction has been translated into many languages in India and abroad.

Land Lust is a translation of Dharti ka Kaal, Joginder Paul's first collection of short stories in Urdu.

Sukrita Paul Kumar,

, a noted poet and critic, was born and brought up in Kenya. She held the Aruna Asaf Ali Chair at Delhi University till recently. Formerly, a Fellow of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, she is also Fellow of the prestigious International Writing Programme, Iowa (USA) and Hong Kong Baptist University. Honorary faculty at Durrell Centre at Corfu (Greece), she is a recipient of many prestigious fellowships and residencies. She has to her credit several collections of poems in English, many translated into Indian and foreign languages. Her critical writings are mainly on partition, modern Indian fiction, and gender. Her latest translations include Blind (novel) and Nude (a collection of poems): A guest editor of journals such as Manoa (Hawaii), she has also held solo exhibitions of her paintings. Many of Sukrita's poems emerged from her experience of working with homeless people and tsunami victims.

An author, translator, and editor

Vandana R Singh

was given the Award of Recognition for Outstanding Contribution to Literature by the Chandigarh Sahitya Akademi. Her literary translations from Hindi to English have been published earlier. She has authored several books on Communication Skills and ELT for Oxford University Press. She has been a consultant editor for several UN organisations and textbook developer for NCERT & NIOS. A PhD in Indian writings in English, she has been Associate Professor of English at GCG, Panjab University, and has worked as a bilingual teacher for the Manchester Education Committee, UK, A keen gardener and bonsai enthusiast, she views translation as a social responsibility contributing to building cross-cultural bridges. She is fascinated by words—their origin and evolution.

Soon after the Partition of the country and just after getting out of the refugee camp in 1948 at Ambala, when Joginder 138 Paul was a young twenty three-year-old writer, he married a girl 140 from Kenya on the condition that they would settle in Kenya. A refugee that he was anyway, he migrated with her to a country 144 which was still in the clutches of the British rule while, ironically, his own country India had just won its hard-earned freedom. Pained by the social inequality and racial discrimination that he witnessed in everyday life there, he felt like a complete outsider. The Asian community around him seemed to accept that social reality as a given and, in fact, participated fully in its perpetuation. He considered himself 'in exile', and longed to get back to his homeland from the day he landed there.

The stories in this volume emerged from his anguish and sensitive observation of the lives of Asians living in Kenya, especially in their relationship/non- relationship with Africans. Originally called Dharti ka Kaal, Land Lust is a collection of eleven stories that capture the spirit and social ambience of Indians living in pre-independence, colonised Kenya. The presence of African characters in these stories, in a way, asserts the dignity of the black people otherwise invisible in urban social domain there.

The Kenya of 1950s was a multiracial society where the British, Asians, and Africans co-existed in a harshly xenophobic environment. The lure of money, 'development project' of African cities, the beautiful weather and the 'highlands' drew people from all over to Kenya. The stories in this volume unravel the sensitivity of the author to the incipient racism and the operative colonial hierarchies, as also the tussle between nature and 'development'.

Jambo Rafiqui, one of Paul's most brilliant stories in this book, deftly explores the naivety of the locals while also giving us a glimpse of the social pecking order, complicated as it is by the presence of Asians who hang in an uneasy balance between the black and the white. Here and elsewhere too what quietly emerges is the belief in the superiority of one's own race that runs uniformly across the spectrum — it's a different matter that only the colonisers overtly declare themselves to be so.

The dynamics between different races and cultural groups takes on thought-provoking overtones when we see Indians having absolutely no doubt about their own superior culture, and ruing over the fact that there is no 'life' in Kenya and no intelligent people to have a decent conversation with. This coming from people with a two hundred-year-long history of being colonised themselves gives a glimpse of a knotted world where the oppressed waste no time in reinventing themselves as oppressors. Most Indian characters seem to suffer from complete amnesia regarding the recent Partition of their own country — a haphazard decision perpetrated by the very same imperialists with whom they tend to mindlessly align themselves in another colonised landscape. And so, we are face-to-face with a tangled, convoluted world where racism doesn't come only in shades of white and black but is a knotted web with liberal sprinkling of brown. Interestingly, and sadly, most of these themes are still alive today. The context of the stories is historical but the themes are as relevant today as then.

While in one of the stories young African boys are asked to dive into a killer lake for a coin by an Asian family, in another story, Jaroge — an enthusiastic and well-meaning African employee — becomes a victim of institutional racism when he is abruptly fired from his job.

Joginder Paul's fiction does not ignore any of the harsh aspects of the social reality in Kenya then — be it racism by the British government, in educational institutions, by farm owners, businessmen, or staid homemakers. Paul can see through it all, and create a world around these themes for the readers to get a peek at the bleak, deeper reality under the superficial cheer of a large class of people in Kenya in mid-twentieth century. Irrespective of where one was situated in the social ladder or positioned in a given power structure, most people seem to be content with the state of affairs.

Through these stories, Joginder Paul's keen eye and artful storytelling brings alive an empathy for fellow human beings, evoking the reader's capability to see beyond opaque exteriors. This is something as desirable today as earlier when the stories were written. The social follies, political foibles, and oppressive power structures continue to exist and percolate into everyday lives of ordinary people. While the stories in Land Lust offer a poignant slice of colonial history of lives led in the pre-independence multiracial Kenya, we believe they bring to the fore themes of universal appeal across cultures and time.

When I first met Joginder Paul, his demeanour, his manner and personality led me to think that he was a wealthy connoisseur of jewels. Soon, I realized I was not very much off the mark. A connoisseur indeed, but not of gold and silver. He is a connoisseur of stories; he is prosperous, but only in his art.

Joginder Paul has ushered a new ethos into the world of Urdu short stories. Africa is not merely a land of green parrots and long-necked giraffes. A lot of people tell tales about a kind of Africa that is barbaric. Joginder Paul talks of people who are referred to not just as Africans but as habshis. All sorts of ugly stories about their character and personality have been instilled into our consciousness. Not only does Joginder Paul demolish incorrect tales by introducing new characters in the new environs, he also tells us very interesting things about the social reality of colonial Kenya and its people. He is the first Urdu writer to have walked us through the many facets of African lives with such finesse and expertise.

Paul has his own distinct point of view. Most people don't have any specific way of looking at things. They stop and see, entertain themselves and walk away. Indeed, that in itself can also be seen as representative of a point of view, but an extremely superficial one. Joginder Paul too stops and looks; he too entertains and walks away but even after his going away, we keep relishing his short stories because the scene he presents to us is not superficial like in many other cases. His stories present several layers of meaning which he slowly unfolds and seems to find joy in doing so again and again. What peeps from his stories is the heart of an empathetic writer, someone who is pro-humanity. He is not merely like the plate in a camera on which the surface surroundings are imprinted, he possesses an empathetic perspective too. He has the space in his heart for the other's pain and anguish. Inside many other writers is placed merely a camera and in place of a heart, there is a typewriter.

Joginder Paul is fortunate that he is not one of those writers. He has a distinct, humane point of view that looks to the betterment and welfare of people. Moreover, he is fully conscious of the responsibility of his pen.

Paul is a young writer who belongs to the new generation. I am not really concerned about who belongs to the new or the old generation; I am only bothered by who writes well and who doesn't, who is a good writer and who isn't. Some people may start writing well at the young age of twenty while others are destined to acquire the fine art of writing much later, sometimes only after crossing the age of fifty. Different kinds of examples are found in literature. In order to assess someone's writing, age is certainly not a criterion to be bothered about. What needs to be discerned is whether the writing measures up to being good literature.

As an admirer of English literature, Joginder Paul has learnt a lot from Western literature in relation to his own writing, like all of us have. But in as far as his point of view is concerned, it is in no way 'Western'. In general, artists don't seem to be engaging with the living and changing realities of the East, in the same way as others tend to ignore the larger realities of the world. Much against their wishes, perhaps, the major focus of the world today seems to be shifting from art to science, and then from science to politics. Perhaps the writer is unable to first face and then accept this phenomenon. That is why they tend to become inward and remain busy with their internal life.

Not so in the case of Joginder Paul. He cannot be accused of being dismissive of the social and political realities of the world outside of himself. He could very easily have suppressed his awareness and anxieties about his immediate surroundings; he could have ignored deeper realities and remained at the surface level by depicting the colours and shapes of superficial reality through his fine art. But he did not do this, and in not doing this, he worked with great courage. Paul's context is that of East Africa. The people of East Africa are like the Pathans of the subcontinent — straightforward and simple. They have a rather uncomplicated sensibility. Here if Nature is elemental, the human being too is like a child, innocent and trusting. Some people who went there from the West have created settlements there. They have built railways and mines, cleared forests, cultivated farms in the valleys and while doing this, they have — like in the other parts of Africa — made East Africans dependent on themselves. In this way, neither does the land or the country belong to Africans, nor is the rule theirs. While they are in their own country, they have become servants of people from outside. There are some Hindustani people amongst them too who — though on a smaller scale — also exploit the Africans. These are some basic facts regarding life in East Africa today which, if ignored, would mean dismissing very important realities of life there.

Joginder Paul could have entertained himself by simply presenting what he witnessed as the lives of the rich and the glamorous world of the outsiders. Those would have been fun stories through which the self-centred reality of those people could have been revealed. While the joy of reading the stories is retained by the writer, thanks to his exposure to Western literature, he also weaves a creative intrigue in his stories. He knows very well how to give a bit of a jerk or a surprise at the end of the story. There is not a single sentence more than necessary in his writing and, unlike some older writers like myself, he does not lean on surfeit of words. He comes across as very knowledgeable about the art of writing a short story and, within this form, he does not need to learn from anyone. By remaining truthful to his art, he has, in fact, chosen to be on a very difficult path. His sympathies are not with the profiteering foreigners, nor is he biased or aligned with the people from his own country. His empathy is with the poor native Africans who actually belong to that country and are determined to fight for their freedom.

.

What kind of people are they? What kind of lives do they lead? How do they love? What kind of land do they live on? What is its shape and colour? What has the so-called new civilization brought into their old jungles? Don't listen to the wondrous tales about all these matters from me. Listen to them from Joginder Paul who has narrated them beautifully, artfully, and aesthetically through this collection of short stories in a way that life in Africa comes alive and flashes with its varied colours in the eyes of the reader. .

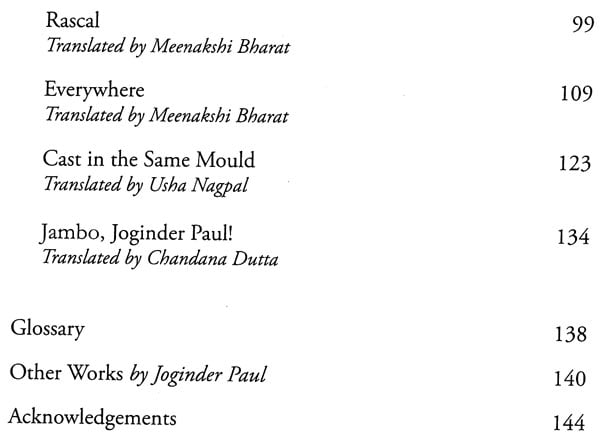

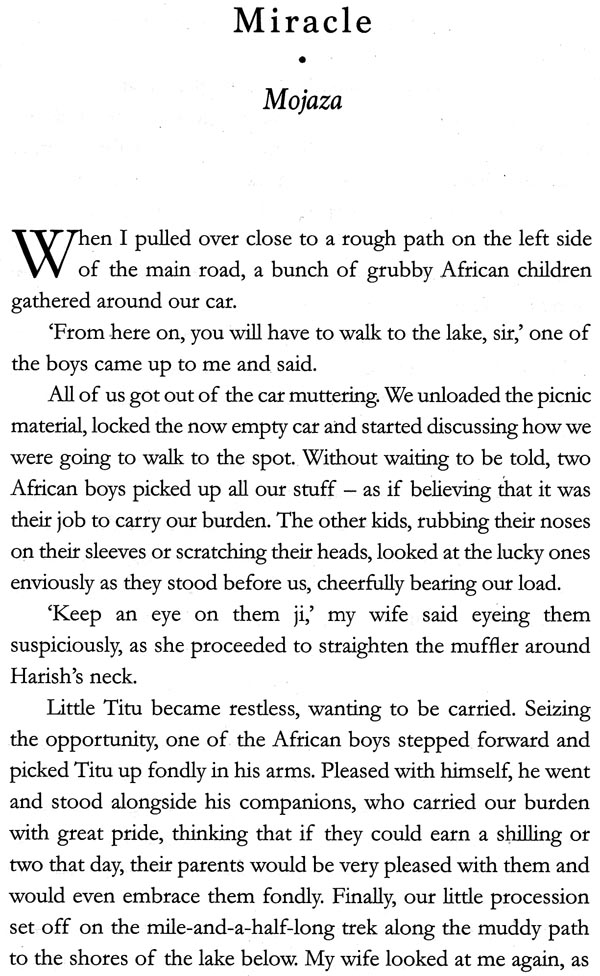

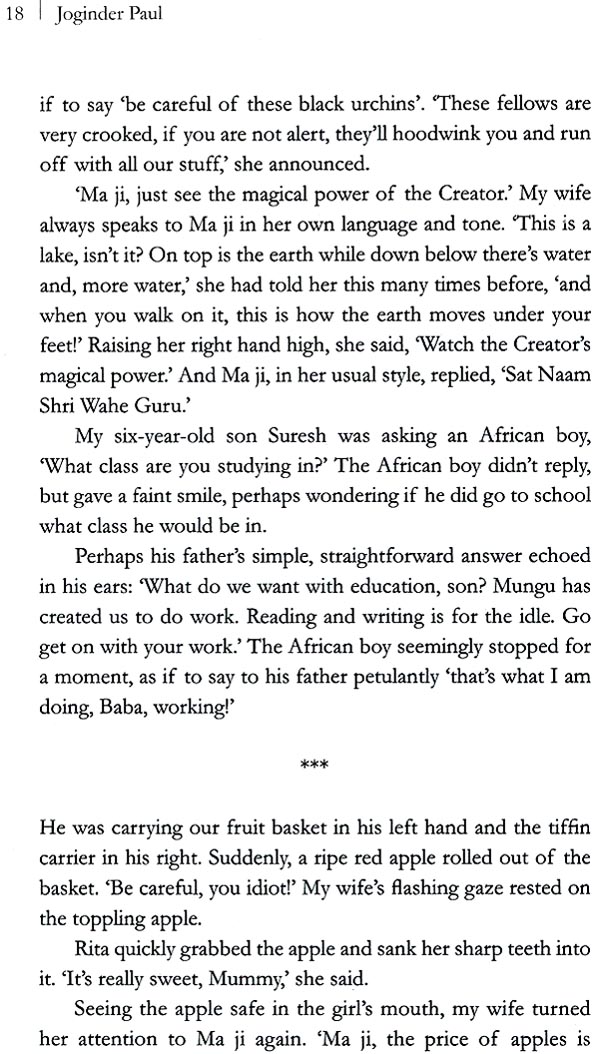

**Contents and Sample Pages**