The Lost Generation (Chronicling India's Dying Professions)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM004 |

| Author: | Nidhi Dugar Kundalia |

| Publisher: | Random House India |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9788184007374 |

| Pages: | 272 (14 Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 7.5 inch x 5.0 inch |

| Weight | 200 gm |

Book Description

A young journalist based out of Calcutta, Nidhi Dugar Kundalia is an MA from City University, London. She has written extensively on society, subcultures and cultural oddities in newspapers like The Hindu, the Times of India and magazines like Kindle Magazine and Open. This is her first book.

I first saw him in Tiretti Bazaar in the early hours of the morning, when it is still possible to walk and observe the activities before crowds throng Calcutta’s old quarters. Tea-stall owners juggling streams of tea between glasses; a street barber sharpening his razors against a stone; a beedi maker drying his tendu leaves on the cobbled sidewalks. He sat between them, our bhisti wallah—the water carrier—before the corporation taps, suspended between old and modern, waiting to fill his animal-skin bags with water. His ancestors, though, would fill their water from the banks of the Ganga and freshwater springs, serving Mughal troops in war fields, the Nawabs of Bengal and then the British. The bhisti wallahs were crucial machinery in ordinary people’s everyday lives too—watering the gardens of zamindars, filling pots of water for the nautch girls, offering cool water to worshippers at mosques on the days of Jum’ah (the Friday prayer) and filling cups for weary travellers and thirsty lepers. As the century turned, however they quickly devolved into mere spare parts, only delivering mashqs to those whom the government pipelines had failed to reach. Like the old, abandoned palatial homes of the noblemen dotting this congested marker, this solitary bhisti wallah is a testament to significant events and feats of importance from decades ago, but like their deepening cracks and crumbling walls, he is also a stark reminder that, one day, dust only goes to dust.

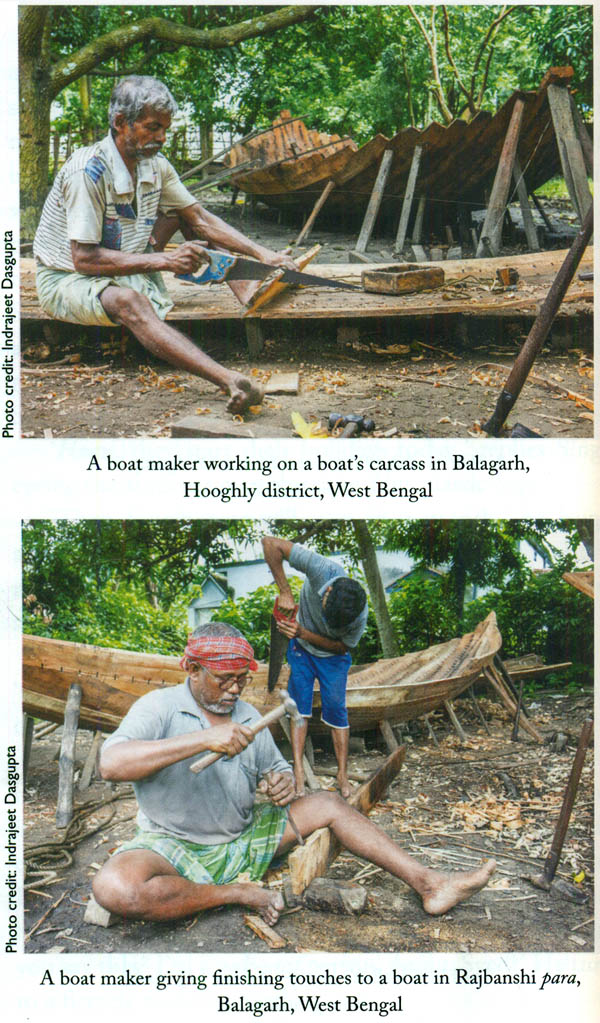

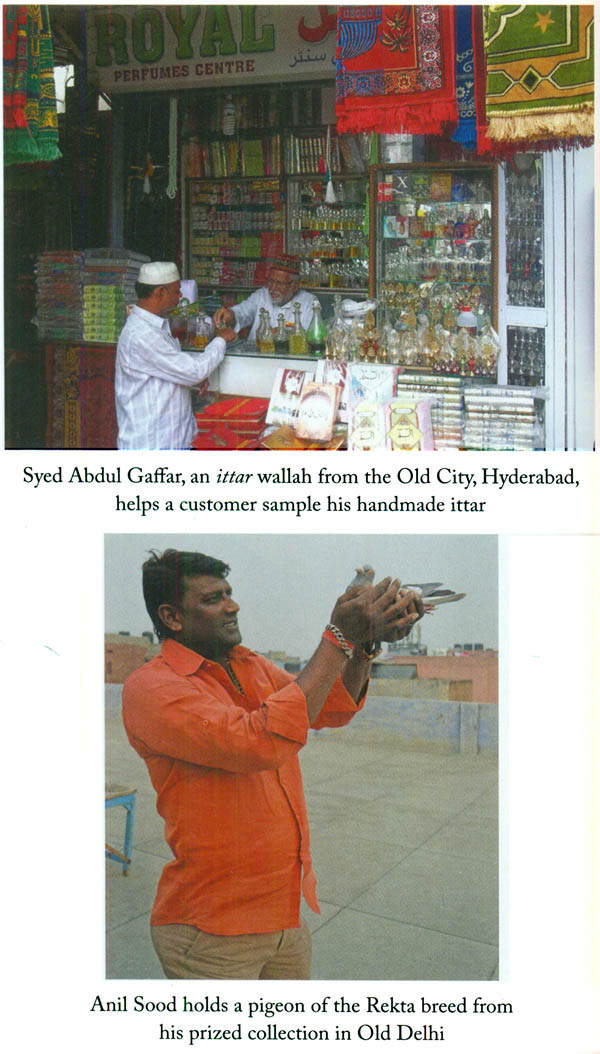

The streets in the ancient cities of India are suspended in a time warp—not the lofty, shiny lanes of the city, but the old, faded, deceived to-be-pulled-down-any-time-now streets. A perpetual sense of nostalgia lingers in these old neighbourhoods, a sense of belonging to a time you were not born in. Buildings, lives and occupations that were integral to existence in the past still exist here, although you only catch glimpses of these in the cities’ decaying old streets, below disintegrating edifices and, often, in the villages on the fringes of the vast metropolises. Bhisti wallahs, beedi makers, wigmakers, postmen, wooden-boat makers, entertainers, storytellers, letter writers, ittar wallahs—the professionals who were such an integral part of everyday life centuries ago are fading into oblivion, fast giving up their ancestral professions.

Scribes who manually copied books were replaced by printing presses followed by the computer. Radios and televisions cut into the livelihoods of nomadic storytellers. SMS technology caused the death of letter writers. Much has been said and written about this Disneyfication of the subcontinent, but little has been said about the debris left behind by the globalization that is rapidly transforming the originally diverse and syncretic Indian society. Resultantly, the hapless last generation of these ancient professions have been left wondering about the bleakness of their futures. The scribe who teaches calligraphy at an academy in Delhi told me while we chatted in his class, ‘We struggle to make Urdu survive, let alone Urdu calligraphy, in this digitalized world. It is like being on a small raft in the middle of the ocean, drifting on it for days and nights, with the only incentive being more of the same—blue against blue.’

On my travels around India, I found the new and old worlds intersecting in unpredictable ways even as modernization spreads through the country. Outside Vikarabad, in Telangana, I met in a church compound a lady gravedigger who had taken up her father’s job—a lower-caste job originally reserved for men—despite protests from her community. On the one hand, her Christian community objects to this feminist stance and, on the other, they lobby and protest outside government offices against caste discrimination, asking to be granted scheduled caste status. The members of the community were originally Hindu Dalits who had converted to Christianity over the years, but the retrogressive practices and prejudices against them haven’t changed much. Indian law, unfortunately, does not say anything about ‘Untouchable Christians.’

In Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, a midwife, or dai, provides training to other women in midwifery practices because of her distrust in modern birthing practices at today’s hospitals. She limits her teachings to traditional midwife castes, which were essentially a lower caste. ‘It is to preserve our ancestral professions,’ she told me defiantly. In villages, it is not uncommon for affluent families to bestow land grants to a dai’s family and give her the sole rights to deliver babies in their household.

India’s professions have always been interlinked with caste practices that dictated the professions of castes and its many subsets. Occupations were meant to be passed on from father to son, and the option of transitioning from one profession to another was generally outlawed. The Kayasth class, who comprised the upper layer of Hindu society, occupied high governmental positions, often serving as administrators or advisers. The lower classes such as the nais or the chamars performed the menial jobs of barbers and tanners, respectively, while their wives doubled up as masseuses or pedicurists for the women of the aristocratic families. The rudaalis, or the professional mourners, whom I interviewed for this book are an example of caste-induced professions too. It is customary in Rajasthan for higher-caste women to not mourn publically, and so the rudaalis— mostly helpless, impoverished women caught in the web of caste hierarchy—step in to mourn on behalf of these upper-caste women, representing their sorrows for the traditional twelve-day mourning period. But the changing times, enculturation and automation are all slowly eliminating these mourning practices, consigning them as some sort of an anthropological curiosity. Increasingly, jobs are being taken up for monetary reasons, and technology is helping them switch quicker to economically viable jobs. No caste exists for a call-centre employee or a computer operator, for example.

To those who belong outside caste-bound practices—the calligraphers, the kabootarbaaz, the ittar wallahs—their professions have suffered because they lost their patrons in the kings, noblemen and moneyed zamindars of pre-Independence India. I must mention the incredible contribution of the Mughal empire, particularly Emperor Akbar. Almost five of the eleven professions I cover in this book gained prominence during the regime of the empire which was steeped in Parso-Arabic values along with Hindu influences.

Sometime during my travels I started working on this book, The Lost Generation. A few stories had taken me to the boondocks, far beyond the urban reaches of the states. I bumped into Naxalites, activists, thugs and ruffians, but rather than obstructing the story in any way, they helped me understand the complex social fabric of our vast country. To protect their identities and interests, in some cases I had to change their names or modify the factual matrix. Through our conversations, I saw that their paradoxes provided for a deeper understanding of issues rather than cause moral obstructions—all contributing to appreciating the frailty of the human condition. Like one of the readers of an early draft of this book said, ‘There are hardly better ways to expose vulnerabilities and contradictions than reproducing the seemingly banal Conversations about people’s “ordinary lives”.’ In some instances, though, because of certain limitations faced by my translators and to best represent the views of the individuals, I have paraphrased conversations rather than document them verbatim. I have tried, then, to keep the stories free of authorial interference, something I have allowed to creep into the narrative only when necessary. Inescapably, however, I ended up directing the conversations to areas of my own interest, and I hope these areas interest you, the reader, as well.

While recording the interviews, I found myself being critical of the patriarchal, casteist, classist and sexist world-view seemingly espoused by these professions and the organized religion they practise. But at the same time I was grieving the loss of these ancient vocations, the cultural diversities and mysterious characters they have produced over the years. By the time I finished working on the book, I hoped to have arrived at a conclusion. I wish I could have assertively stated that these professions have been culturally exhausted, that they have lived out their natural lives, that they, then, have to go—that the world doesn’t need the bhisti wallahs to exist if they have become an anachronism.

But then I don’t make my living as a bhisti wallah.

| Introduction | xi | 1 | The Godna Artists of Jharkhand | 1 | 2 | The Rudaalis of Rajasthan | 17 | 3 | The Genealogists of Haridwar | 39 | 4 | The Kabootarbaaz of Old Delhi | 61 | 5 | The Storytellers of Andhra | 83 | 6 | The Street Dentists of Baroda | 103 | 7 | The Urdu Scribes of Delhi | 123 | 8 | The Boat Markers of Balagarh | 141 | 9 | The Ittar Wallahs of Hyderabad | 157 | 10 | The Bhisti Wallahs of Calcutta | 173 | 11 | The Letter Writers of Bombay | 191 | Acknowledgements | 205 | Notes | 209 | Glossary | 227 | Bibliography | 239 | A Note on the Author | 247 |