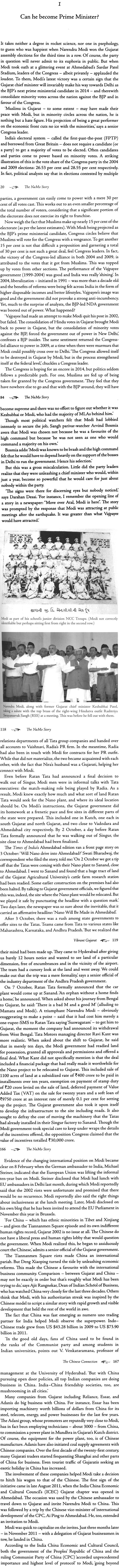

The Namo Story (A Political Life)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG365 |

| Author: | Kingshuk Nag |

| Publisher: | Lotus Collection and Roli Books |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2013 |

| ISBN: | 9788174369383 |

| Pages: | 200 (12 B/W Images) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 280 gm |

Book Description

One of the truly enigmatic personalities on the contemporary Indian political canvas, Narendra Modi is difficult to ignore. From his humble beginnings as a RSS pracharak to his rise in the Hindutva ranks, and from being Bharatiya Janata Party’s master planner to one of its most popular of controversial state chief minister, Modi’s manta of change and development is gradually finding many takers. Through he evoke vastly different reactions among the citizens for his alleged role during the Godhra aftermath, what is absolutely clear is that he indeed is racing toward s the centre stage, making the 2014 General Elections look more like a Presidential system - where, you either vote for him or against him. And that, as they say, is the Modi effect. Kingshuk Nag paints the most vivid portrait of the extraordinary political who is poised to take on a new role in the coming years.

Kingshuk Nag was the resident editor of the Times of India’s Ahmadabad edition between May 2000 and July 2005, which was the most eventful period in the history of Gujarat with a major earthquake and deadly riots. He received the Prem Bhatia Memorial Award - which is considered the Indian equivalent of the Pulitzer - for demonstrating excellence in political reporting and analyses in Gujarat. Presently the Resident Editor of the Times of India’s Hyderabad edition, this is Nag third book. Alumnus of the Delhi School of Economics, Nag writes a hugely popular blog titled ‘Masala Noodles’ on the TOI site.

You can love him, or hate him, depending upon your predilection, but there is no way that you can ignore Narendra Modi. He is one of few, truly enigmatic personalities gracing the contemporary Indian political scene. This is my raison d'etre for writing his biography. As early as 2004, I could discern that this man would leave behind all his political rivals, including his (then) godfather L.K. Advani, and become the Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP) official prime ministerial candidate.

In 2009, I was confident that Modi's moment had come, but the opposition within and outside the BJP was so strong that the man had to cap his ambitions for a few more years. In mid-March 2013, as I write this note, there are clear indications of the fact that Modi is racing towards centre stage, aided not only by his resolve but also a weakening Congress regime. His forceful speech, promoting the Gujarat model of development as an alternative to that of the ruling Congress alliance and delivered to the enthralled students of the Delhi University's Shri Ram College of Commerce (SRCC) is a clear indication of his intentions. But the protests that raged outside the college show the opposition that he will have to face on his journey to 7, Race Course Road. They also demonstrated the vastly different reactions that he evokes among the citizens. That this was not an isolated incident is clear from the proposed video talk that Modi was to deliver to students ofWharton in the beginning of March 2013. Even as the talk scheduled was cancelled following protests from a section of the university faculty and student bodies, there was a howl of counter protests. Barely a fortnight before his SRCC speech, Modi offered the services of ' the BJP's Gujarat unit' to the new BJP boss, Rajnath Singh, to strengthen the party nation-wide. Considering that the BJP's Gujarat unit is nothing but Modi (the BJPs Gujarat unit president, an unassuming gentleman lost the 2012 polls as even Modi romped home victorious for the third time), this was a thinly-veiled proposal to be made the prime ministerial candidate for the 2014 general elections. Taking a cue, BJP's senior leader Yashwant Sinha was quick to openly demand that Modi be declared the party's prime ministerial candidate, as his candidature would result in the party getting more votes and seats. Sinha said that during his travels across the country, he had encountered numerous demands from BJP workers and common people that Modi be declared the candidate for the highest executive office. Former actor and now BJP Mp, Shatrughan Sinha seconded his proposal even as the new party president, Rajnath Singh, warned party workers against airing their views in public. His contention: it is an intra-party matter and must be decided by BJP's Parliamentary board. Rajnath's warnings (read fears) have fallen on deaf ears as more and more BJP members are joining the Modi bandwagon. Over the next few months, the numbers are bound to swell as the chorus for Modi will reach its crescendo. But let us not harbour any illusions: much of this hype could be the result of a well-orchestrated effort, blessed by none other than Modi himself.

Sinha has vociferously demanded Modi's candidature, but I am not sure how well the two know each other. I have discovered that strangely, most of Modi's fans are not known to him at personal level. Those who do, mistrust his ambition. Modi is highly individualistic and has no friends or family that he is close to. He lives alone and even his mother, who resides with his brother in Gandhinagar, does not come to stay with him. In India, this seems a trifle surprising. But as I said, Modi IS unique. Nobody can take him for granted, not even those whom he works with closely. I have seen many politicians of Modi’s own party trying to get his horoscope analyzed by astrologers, in an attempt to figures out what he will do next! The Congress party, clearly on the back foot by the Modi onslaught, is still trying to figures out how to deal with him effectively. The grand old party’s responses are mixed and varied. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, for long the butt of jokes of Modi, reacted by commenting in Parliament that ‘jo garajte jai, who baraste nahin’ (those who make tall claims do not deliver). This was in response to Modi's description of the Prime Minister as a 'night watchman' (keeping the wicket safe for Rahul Gandhi). Rahul himself declared Bheeshma like that he would not marry in what was seen as a counter to Modi who never tires of declaring that he does not have a family and thus has no vested interests. However, it seems that like before, the Congress calculates that Modi's controversial image that draws extreme reactions will stymie him. Modi is also aware of this but hopes that if a government delivers good governance and (as he told Indo-Americans in a video address) 'serves the people selflessly then the people will forget the government's mistakes: This can be read as his fervent prayer that his track of delivering on the economy front will make the voters forget about Godhra.

A book on Modi and Gujarat has been on my mind since the 2002 riots. When I approached a well-known publisher with my book idea, he was candid: 'Write a book from the Hindu point of view and I will publish it: Disgusted, I shelved the idea. In 2005, I again commenced discussions with a leading publisher, but the project had to be abandoned because this publisher had a diametrically opposite view to the one I held. He felt that a biography of Modi would end up 'lionizing' him.

In July 2012, on a short trip to Delhi, I called on Pramod Kapoor, the publisher of Roli Books and suggested that he allow me to do a biography of Modi that would neither 'demonize' nor 'lionize' the subject. I must thank him and the editorial director of Roli Books, Priya Kapoor, for their faith. Though the information contained in the book was collected over many years, I did not write it at a leisurely pace. From the second week of December 2012 as it became increasingly clear that Modi would sweep the polls once again, the pace had to be quickened. Thanks are therefore due to my editor, Padma Rao Sundarji for coping with the rapid writing towards the end. Neelam Narula also deserves my thanks for fine tuning the copy and ironing out the glitches.

I would also like to thank the management of the Times of India, who resisted tremendous pressure to remove me and allowed me to serve in Gujarat in 2002. I am grateful to my colleagues at the Times of India, Ahmedabad from whom I have learnt an immense amount. Not to forget my wife Swati, who bore my moods.

When Dr Manmohan Singh, then finance minister of India, initiated the process of economic reforms on 24 July 1991, he had, in all probability, never heard of Narendra Modi. Those days, Modi was trying to make his mark in the BharatiyaJanata Party by organizing various yatras for the likes ofLK. Advani and Murali Manohar Joshi. That sultry afternoon, Singh - who, quoting Victor Hugo, described economic reforms for India as 'an idea whose time had come' - would have been startled if somebody had predicted that the process that he was unleashing would, two decades later, catapult this yatra manager to the gates of Delhi, ready to take on the ruling establishment.

The saga of Narendra Damodardas Modi is the story of how money, religion, beliefs and rising aspirations combined to change the course of Indian politics and economy in the last twenty years. It is also the story of the desire for change among people, albeit without consensus on the nature of change they seek. Above all, it is the saga of economic liberalization unaccompanied by political reforms: a process that led the country from one seam to another.

Sheltered far too long by the license raj, Indian industry, by the end of the 1980s, had become noncompetitive and costly. There was no incentive to reduce costs and no focus on quality. Indian wares were not export-worthy and domestic consumers had no choice. For them, it was a take-it-or-leave-it option. Though exports were not increasing, imports were mounting. This led to a continual mismatch between earnings from exports and the costs of imports. As a result, the country's foreign exchange reserves were depleting. In 1991, reserves fell to a level barely sufficient to finance imports for two weeks. Alarmed, the government pledged gold from RBI's vaults in return for foreign exchange.

In order to extricate the country from this financial mess, P.V.. Narasimha Rao, who became prime minister after the 1991 elections, appointed an economist as the finance minister and mandated him to reform the economy.

At the outset, Manmohan Singh devalued the rupee (which made exports cheaper and imports costlier) and removed trade controls. He reasoned that lifting licensing would open Indian industry to competition and compel it to get its act together. As a result, Indian manufacturing would become world class and the consumer would get a huge array of goods hitherto unavailable to him - be it luxury cars, air-conditioners, refrigerators, or washing machines. Above all, this would fuel growth and create employment in a country where the number of unemployed was perpetually rising.

The strategy showed results. Lifting licensing brought in new entrepreneurs in a landscape monopolized by old players whose main strength was to corner licenses, enter into cartel arrangements with eo-producers, push shoddy goods into the market, and generally maximize profits. In pursuance of the Say's law of economics that predicts that 'supply creates its own demand' (and not the other way round, as is generally believed), the Indian consumer began to lap up the new products even as the stock markets boomed in an unprecedented bull run. A large part of this bull run was, of course, speculative, but it brought a lot of money into the system. Buoyed by the India growth story and the stories of the 'elephant on the move' and 'the tiger un-caged,' foreign investors with surpluses began arriving in India in droves. For them, India was one of the few countries where the prospects of increased demand remained high: most of the developed world had saturated markets.

Doing away with industrial licenses had another effect: the scene shifted to states. Previously, it was the business of the Government of India to decide who could manufacture what, and in what quantities. Now, the winds of change had begun to blow. Entrepreneurs could decide what they wanted to manufacture, and more importantly, where. The last was crucial because it drove competition between states to attract investments to their territories. Businessmen were in raptures because they could now command chief ministers and demand the goodies they wanted as incentives to set up plants in their states. At the same time, chief ministers became more important: an enterprising chief minister dealing directly with businesses could create an entirely different political constituency.

An ancient saying in north India lists' zar, zoroo aur zameen (money, woman and land) - though not in the order of importance - as the main causes for human disputes. True or not, the saying reflects the feudal mores prevailing in the country for centuries. Even a few years of liberalization could not change this mindset: businessmen began to clamour increasingly for cheap land in return for investing their money in a given state.

Simultaneously, something else happened. Though reforms were aimed at making Indian industry and manufacturing internationally competitive, entrepreneurs showed more interest in the services sector. This was not surprising considering India's large labour pooL Most of the labour force was young, underutilized and raring to go. More importantly it came cheap and was, by and large, proficient in English. Entrepreneurs realized that this strength of India could be harnessed. Be it information technology (IT), software programming, financial accounting, or information technology-enabled services like call centres or Y2K and medical transcription, India was on the way to becoming the back office of the world. But whether genetic or not, even those Indian entrepreneurs who set up technology companies could not shed this desire to own cheap land.

Jobs in these growing services sectors rapidly led to increased aspirations. Employees began to aspire towards better lifestyles and own their own homes. If their fathers had built their nesting places just before retirement with all the money accumulated in provident funds, the 25+ generation wanted to own property by age 30.

Sensing an opportunity, many entrepreneurs rushed into the realty sector, Many companies set up real estate divisions and mixed the profits from realty with those from their other businesses. By doing this, they lent the illusion of higher profits, which would, in turn, translate into more attractive scrip prices on the bourses. In this way, more funds could be accessed from the market. A good example of such a phenomenon was the seam-struck Sat yam Computers whose promoter Ramalinga Raju's considerable side business - if not his main business - was land purchase and trade.

| Author's Note | ix | |

| Introduction: Winds of Change | 1 | |

| 1 | Can he become Prime Minister? | 19 |

| 2 | Son of the RSS | 36 |

| 3 | BJP's Master Planner | 53 |

| 4 | The Delhi Years | 70 |

| 5 | Riots and After | 85 |

| 6 | Vibrant Gujarat | 106 |

| 7 | Fear is the Key | 124 |

| 8 | The Sadbhavana Experiment | 136 |

| 9 | Modi: The Man | 148 |

| 10 | The Chinese Connection | 165 |

| 11 | Maharrna Modi': Building a Brand | 174 |

| Index | 185 |