Acarya Kundakunda's Samayasara ((Text, Transliteration and Translation))

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDJ009 |

| Author: | Prof. A. Chakravarti |

| Publisher: | Bharatiya Jnanpith |

| Language: | (Text, Transliteration and Translation) |

| Edition: | 2017 |

| ISBN: | 9788126315574 |

| Pages: | 242 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5" X 5.3" |

| Weight | 590 gm |

Book Description

ABOUT THE BOOK

Acarya Kundakunda was the first and foremost of all the Acaryas who flourished after Bhagavan Mahavira and Gautama Ganadhara. Inscriptions and literature hold him more auspicious than the Jaina canons themselves.

Samayasara, one of his monumental works, signified the truth of spirituality. The philosophy interknit in it is of a puritanic type with no room for Tantra and mantra. Acarya Amrtacandra, a great thinker and master of spiritual science of tenth century A.D. tried to beautifully illustrate the metrical aphorisms of 'Samayasara'. Based on the same is the commentary in English by Prof. A. Chakravarti, a leading Indologist of this century.

To introduce both the text and its commentary Prof. Chakravarti had discussed in no less than one hundred pages: Self in European thought, Self in Indian thought, rudiments of Upanisadic thought in the Samhitas, the evolution of the cosmos from the primeval Prakriti, a discussion of dreams and hallucinations: and Self in modern science. Carrying the weight of a post doctoral research, this voluminous Introduction is an appropriate answer to questions like; Is the mechanistic and materialistic philosophy reconcilable with spirituality which is often labelled with intellectual immaturity, primitive superstition and even psychopathy ?

Bharatiya Jnanpith is happy to publish this fourth edition of 'Samayasara' for the eager seekers of truth and reality. Useful footnotes and linguistic corrections in Prakrit metres have been introduced.

Preface

Samayasara is the most important philosophical work by Acarya Kundakunda. It deals with the nature of the self, the term Samaya being used synonymously with Atman or Brahman. The translation and commentary herein published are based upon Amrtacandra's Atmakhyati but some other commentaries are also consulted. Jayasena's Tatparyavrtti and Mallisena's Tamil commentary were also consulted. The extra gathas found in Jayasena's Tatparyavrtti do not give any additional information nor do they affect the general trend of Atmakhyati. Hence the present English translation confines itself to the gathas found in Atmakhyati. It may be mentioned that the Tamil commentary by Mallisena seems to be based upon Atmakhyati by Amrtacandra. Since the work deals with the nature of the Self from the Jaina point of view, the introduction also deals with the nature of the self from other points of view. The introduction is divided into three main groups; the nature of the Self in Indian Philosophy and the same topic according to Modern Science. A rapid survey of Western thought beginning with the Greek philosophers is given in the first part of the introduction, The second part; Indian Philosophy begins with a concise account of the Upanisadic thought with which Kundakunda appears to be acquainted. The modern scientific approach towards the problem of self is also given in the introduction. It is not a detailed account of modern scientific thought; but here an attempt is made to present the modern scientific attitude which is quite different from that of the latter half of the 19th century. The Scientists and Philosophers of the Victorian period were not sure about the nature of the self. Orthodox Physicists and Physiologists treated consciousness as a by - product in the evolution of matter and motion.. Following this dominant attitude of physical science, psychologists also tried to discuss the problem of consciousness without a soul or self. All that is changed now. Scientific writers mainly influenced by the results obtained by the Psychic Research Society now openly acknowledge the existence of the conscious entity, the self or the soul, which is entirely different in nature from matter; it survives even after the dissolution of the body. Researches in Clairvoyance and Telepathy and veridical dreams clearly support the attitude of modern thinkers as to the survival of the human personality after death. Though nothing definite is established scientifically this change of attitude is itself a welcome one. This change introduces the rapprochement between Western thought and Indian thought as is evidenced in the writings of persons like Aldous Huxley. This must be considered as a good augury, because in war-worn world bankrupt of spiritual values there is a ray of hope that the Indian thought of perennial nature may feed the spiritually starved world which is in search of some genuine idea serving as a solace and hope for the spiritually famished humanity.

,p> This book is published as the first of the English series in the Bharatiya Jnanapitha publications. The publication will reveal to the world what Indian thinkers 2000 years ago had to say about the problem of the Self.

A. Chakravarti

Man’s development in all aspects may be described as an attempt to discover himself whether we take the development of though in the East or the West the same principle know thyself seems to be the underlying urge. When we turn to the west we find that the beginnings of philosophy are traced to the pre-Socratic period of Greek civilization.

That was period of culture where Greeks had a form of religion according to which their gods, Athene and Apollo were superhuman personalities trying to help their favorite greeks by taking part in all their struggles. This naïve popular form of religion very soon gave place to a flood of skepticism organized by the school of Sophists. They began to challenge some of the fundamental concepts of religion and ethics. It was when this process of social disintegration was going on that we find Socrates appearing on the scene. Though he was one of the sophists himself he was destructive analysis of Sophism. For this purpose he began to question and to find out the so called educated individuals of the Athenian society. This process of questioning with the object of discovering whether the opponent knew anything fundamental about religion and ethics was designated as the Socratic Dialectic. He would catch hold of a person from the market place who was eloquently haranguing about justice or goodness and questioned what he meant by the Just or the Good. When the opponent gives an instance of what is just or what is good and defines the concept on the same principle. Socrates would confront him with an exception to that definition. This would force the opponent to modify his definition. This process of debating will go on till the opponent gets confounded in the debate and is made to confess that after all he was ignorant of the nature of the fundamental concepts. By this process of cross-examination Socrates exposed the ultra vanity and hollowness of the so-called learned Sophists of Athens. Then he realized himself and made others realize how shallow was the knowledge of the so-called scholar. That was why he obtained the singular testimony from the Delphic Oracle that he was the wisest man living because he knew that he knew nothing. This process of dialectical analysis so successfully employed by Socrates resulted in building up of the Athenian Academy which gathered under its roof a number of ardent youths with the desire to learn more about human personality and its nature.

Plato, a disciple and friend of Socrates, was the most illustrious figure of the school. In fact all that we know about Socrates and the conditions of thought about that period are all given to us by Plato through his immortal Dialogues. He systematized the various ideas revealed by his master. Socrates. He constructed a philosophical system according to which sense-presented experience is entirely different from the world of ultimate ideas which was the world of Reads. He illustrates this duality of human knowledge by his famous parable of the cave. According to this parable, the human being is but a slave confined inside a cave chained with his face towards the wall. Behind him is the opening through which all-illuminating sunshine casts shadows of moving objects on the walls of the cave. The enchained slave inside the cave is privileged to see only the moving shadows which he imagines to he the real objects of the world. But once he breaks the chain and emerges out of the cave lie enters into a world of brilliant light and sunshine and conies across the real objects whose shadows he was constrained to see all along. Man’s entry into the realm of reality and realization of the empty shadow of the sense- presented world is considered to be the goal of human culture and civilization by Plato. Instead of moving in the ephemeral shadows of the sense-presented world, man ought to live in the world of eternal ideas which constitute the scheme of Reality presided over by the three fundamental Ideas Truth, Goodness and Beauty. This duality of knowledge necessarily implies the duality of human nature. Man has in himself this dual aspect of partly hiving in the world of realities and partly in the world of senses. The senses keep him down in the world of shadows whereas his true nature of reason urges him on to regain his immortal citizenship of the ultimate world of ideas. On the basis of this conflict of reason and the senses, Plato builds up a theory of ethics according to which man should learn to restrain the tendencies created by Senses through the help of Reason and ultimately regain his lost freedom of the citizenship in the world of Ideas. The two worlds, which he kept quite apart, the world of ideas and the world of sense-perception, were brought into concrete relation with each other by his successor Aristotle who emphasized the fact that they are closely related to each other even in the case of concrete human life. How an personality is an organized unity of both reason and sense and hence the duality should not be emphasized too much to the discredit of the underlying unity in duality.

A few centuries after Socrates, we find the metaphysical drama enacted in the plains of Palestine. The Jews who believed to be the chosen people of Jehovah claimed the privilege of getting direct messages from Him through their sacred prophets, the leaders of the Jewish thought and religion. On account of this pride of being the chosen people they maintained a sort of cultural isolation from others whom they contemptuously called Gentiles. A tribe intoxicated with such z racial pride had the unfortunate lot of being politically subjugated by more dominant races such as the Egyptians, the Babylonians and finally the Romans.

When Palestine was a province of the Roman Empire ruled by a Roman Governor there appeared among the Jews a religious reformer in the person of Jesus of Nazareth. As a boy he exhibited strange tendencies towards the established religion and ethics which sometimes mystified the Jewish elders congregated in their temples and places of worship. After his twelfth year we know nothing about his whereabouts till he reappears at the age of thirty in the midst of the Jews with an ardent desire to communicate his message. ‘When he began his mission, the Jewish society was marked by an extreme type of formalism both in religion and ethics. The scholars among them who were the custodians of the religious scriptures — Pharisees and Scribes — were so much addicted to the literal interpretation of their dogmas and institutions that they pushed into the background the underlying significance and spirit of the Hebrew thought “d religion. In such a society of hardened Jesus of Nazareth first appeared as a social curiosity evoking in them an intellectual shock which ended in hatred. Here was a person whose way of life was a challenge to the established traditions of the Hebrew religion. He freely moved with all classes of people, disregarding the social etiquette. The elders of the Hebrew society therefore were shocked when they found the so-called reformer moving freely with the publicans and sinners. When challenged he merely replied that only the sick required the healing powers of a doctor. He was once again questioned why he openly violated the established rules of conduct according to the Hebrew religion. He answered by saying, ‘Sabbath is intended for man and not man for Sabbath’, thereby proclaiming to the world in unmistakable terms that the various institutions, social and religious, are intended for helping man in his spiritual development, and have no right to smother his growth and impede his progress. He enthroned human personality as the most valuable thing, to serve which, is the function of religious and ethical institutions. He told the Pharisees and Scribes frankly that the kingdom of God is within. Though in this conflict between the new reformer and the old order of Pharisaism the latter succeeded in putting an end to the life of the new leader, they were not able to completely crush the movement, disciples recruited from the unsophisticated Jewish society firmly held fast to the new ideas of the Master and went about all corners of the country publicizing this new message. From the Roman province of Palestine they made bold to enter into Rome, the very capital city of the empire, and ardently preached what they learnt from their Master They were suspected to be a subversive organization and were persecuted by the Roman authorities. Undaunted and uncrushed by persecution the movement was carried on in the catacombs till the new idea permeated to a large section of the Roman population. Romans had hitherto a naive realistic form of religion after the pattern of the Greek Religion of the Homeric Period. The advent of Christianity resulted in the breaking down of these primitive religious institutions of the Romans. This breakdown of traditional Roman religion brought many recruits to the new faith from the upper strata of Roman society, till it was able to convert a member of the imperial household itself. The condition of the Roman society was extremely favorable to this wonderful success of the new faith.

The Roman Empire which had the great personal revenues pouring into the Imperial Capital converted the Roman citizens from ardent patriots of the Roman Republic into debased and demoralized citizens of the Imperial Capital sustained by the doles offered by the provincial pro-consuls. They were spending their time in witnessing demoralizing entertainments and in luxuries. For example, the Roman citizens entertained in the amphitheatre to witness the slaves being mangled and torn by hungry lions kept starving for this purpose. it is no wonder that such demoralized social organization complerely collapsed when it had the first onslaught from a more powerful idea and certainly a more soul-stirring message.

The Roman Empire became the Holy Roman Empire in which there was a coalition f the authority of the states with that of the Church. This holy Roman Empire which had the Church and the state combined had rendered wonderful service to the whole of Europe by taking the Barbarian hoardes of various European races and converting them into chivalrous Christian knights by a strict religious discipline imposed on them by the various self sacrificing orders of the Medieval monasteries. This education of the inferior races through strict discipline enforced by the Roman Church had in its own turn a drawback cautioned against by the founder of Cristianity. The Roman Church so jealously guarded its power influence that it did not promote any kind of free intellectual development suspects to be of a nature incompatible with the development suspected of the church. This process of disciplinary suppression of the development of human intellect went for several centuries which are designated as the dark ages by the historians of Europe. But human intellect can never be permanently suppressed like that.

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Prof. Appaswami Chakravarti

A Nayanar by caste and a practising Jain by faith, Rai Bahadur Prof. A. Chakravarti, 1880 - 1960, was one of the most prominent indologists. He was a Professor of Philosophy in the Government College Kumbakonam wherefrom he retired as Principal in 1938.

A versatile scholar of Sanskrit, Prakrit and Tamil, Prof. Chakravarti was equally well - versed in western philosophy. He is also known for his comparative and analytical approach to philosophic problems in the light of modern researches. It is abundantly evident in a number and translated with voluminous introductions, viz. Pancastikaya - sara of Kundakunda (1920); Nilakesi of Samayadivakara Muni (1936); Tirukkural of Thevar along - with its commentary of Kaviraja Panditar (1949); Tirukkural with English translation and commentary, which was described by M.S.H. Thompson in the J.R.A. Society, London, 1955, as 'an indispensable aid to the study of Tirukkural', the Tamil Bible; Samayasara of Acarya Kundakunda (1950)

Apart from a number of essays published in the Cultural Heritage of India, Philosophy of the East and the West, Jaina Gazette, Aryan Path etc., he authored some unparalleled books like the Jaina Literature in Tamil, The Religion of Ahimasa, and so on.

| Introduction | 17 |

| Chapter I | |

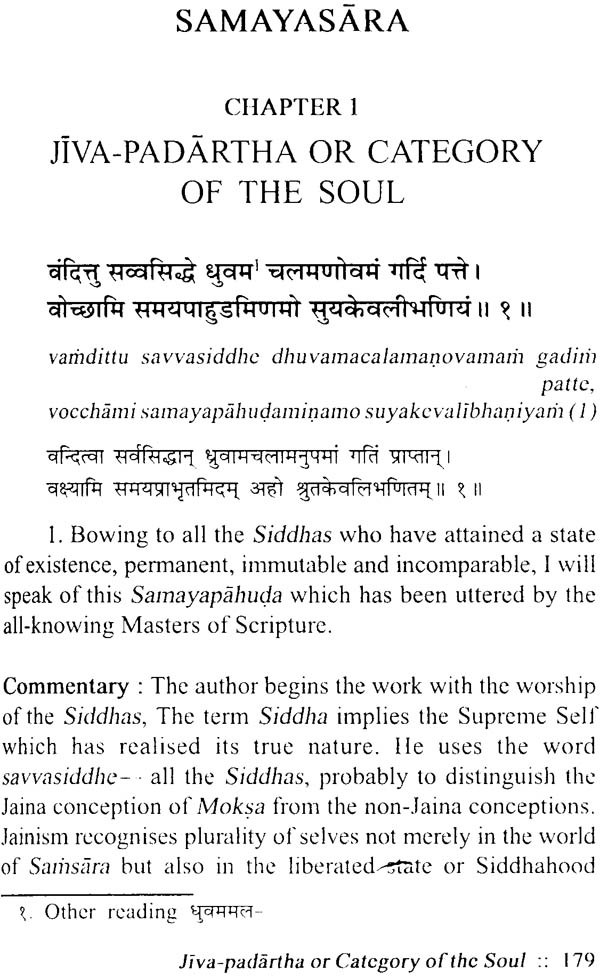

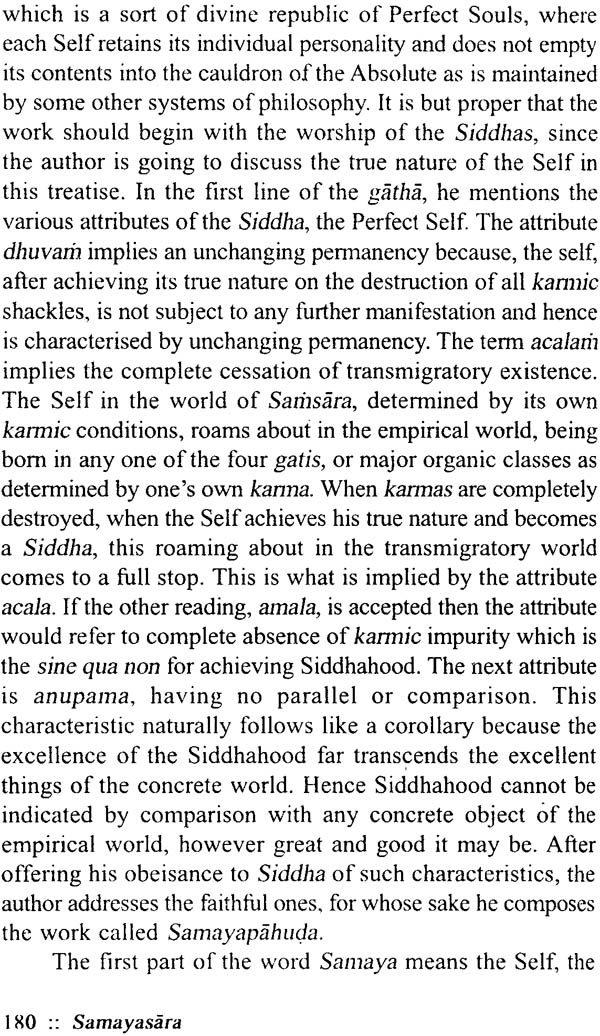

| Jiva Padartha or Category of Soul | 179 |

| Chapter II | |

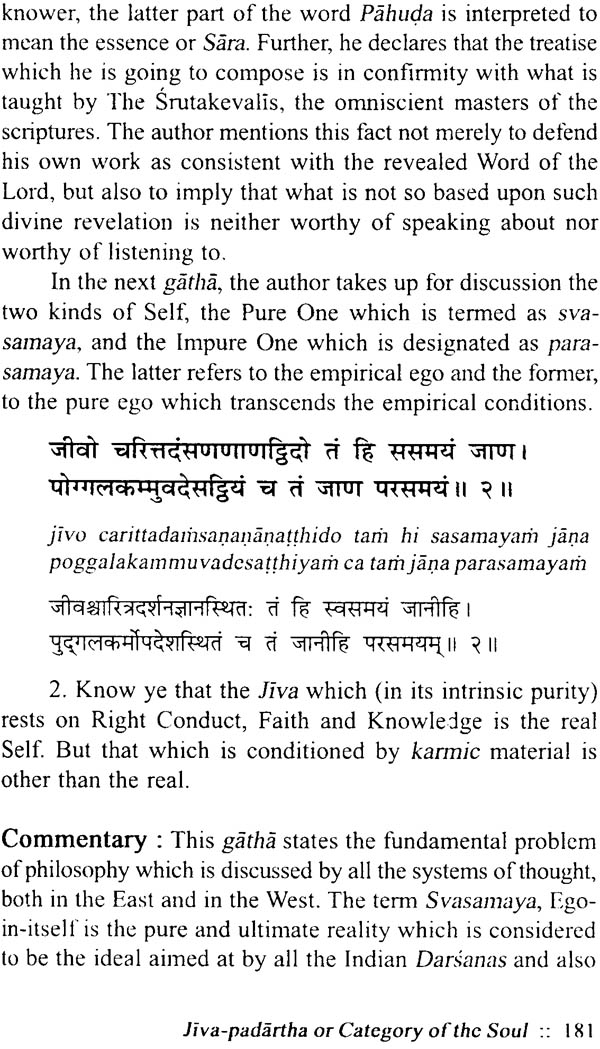

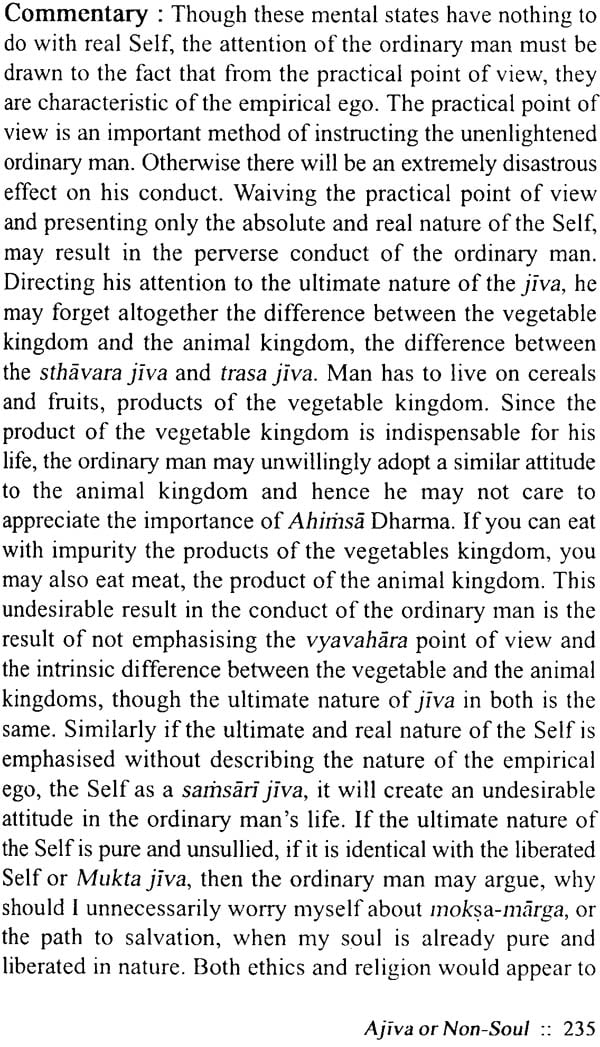

| Ajiva or Non Soul | 229 |

| Chapter III | |

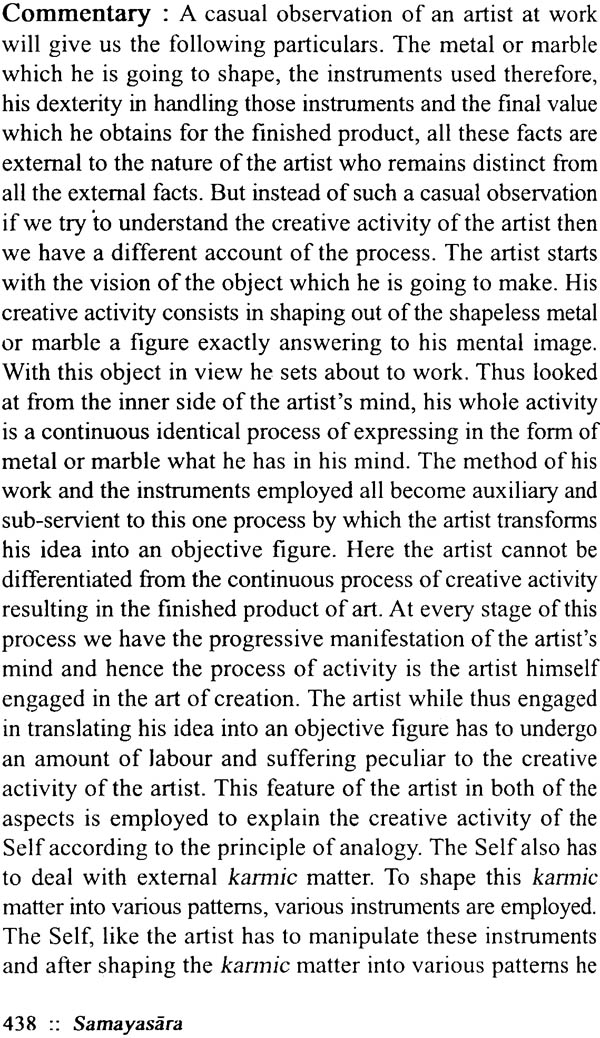

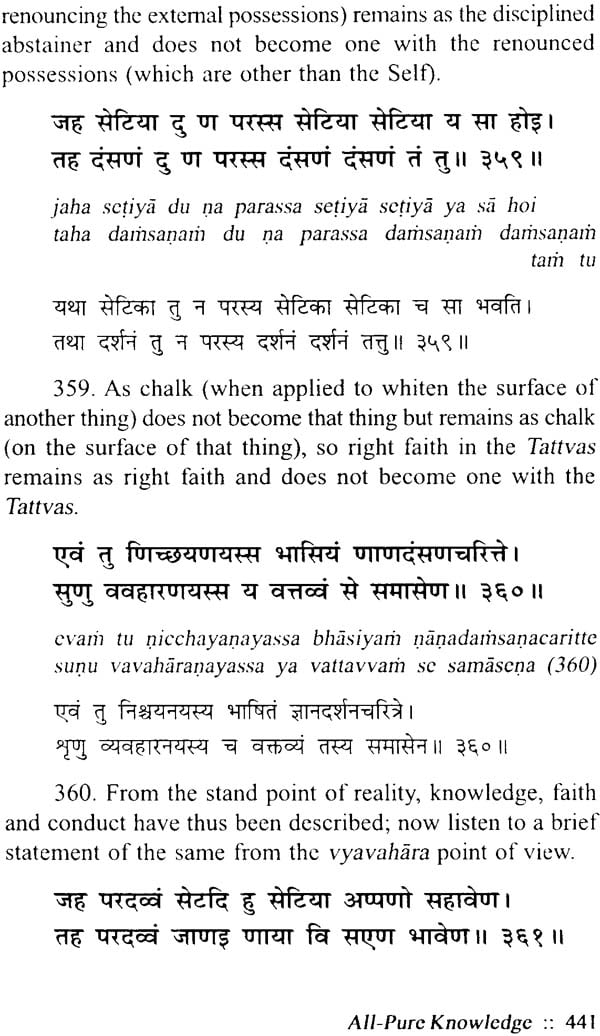

| Karta and Karma the doer and the Deed | 256 |

| Chapter IV | |

| Punya and Papa Virtue and vice | 311 |

| Chapter V | |

| Asrava or Inflow of Karma | 322 |

| Chapter VI | |

| Samvara Blocking the Inflow | 332 |

| Chapter VII | |

| Nirjara Shedding of Karmas | 340 |

| Chapter VIII | |

| Bandha or Bondage of Karmas | 369 |

| Chapter IX | |

| Moksa or Liberation | 400 |

| Chapter X | |

| All pure knowledge | 413 |

| Gathanukrama | 473 |