After Many Autumns (A Collection of Chinese Buddhist Literature)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAJ868 |

| Author: | John Balcom |

| Publisher: | Buddha Light Art and Living Pvt Ltd |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9789382017004 |

| Pages: | 414 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 450 gm |

Book Description

Fifteen hundred years of Chinese Buddhist poetry and prose is brought together in After Many Autumns: collecting the voices of monastics, hermits, sages, and scholars as they share China’s Buddhist history in their lives and work. Representing a wide range of subject matters and styles, the collection hums with celebrations of meetings and partings, of lyrical longings for days gone by, of form and emptiness, all against the backdrop of nature’s infusing light and shadow on personal moments of enlightenment. Fluidly translated and annotated, and complete with biographical and historical notes, After Many Autumns is an ideal companion for lovers of impactful writing and spiritual wisdom.

There have been few collections that attempt the goal of After Many Autumns, and none with its specific scope: to collect great works of Chinese Buddhist literature throughout the history of Buddhism in China. Inclusiveness was a guiding principle of the collection. Though much of the writing is drawn from the Chan School, other Buddhist traditions and lineages are included as well. Many of the selected authors are monks, though works by female monastics are also featured, in addition to the writings of rulers, scholars, merchants, and hermits. Poetry is the dominant genre, though several prose works are also included, with several poems realized in beautiful calligraphic script, itself its own separate art form.

What the selected works share is a heritage of Buddhist themes and imagery, in all its staggering variety. The level of Buddhist content of the works vary. Some are direct, doctrinal expositions, others deal with Buddhist concerns, and some are simply informed by a Buddhist aesthetic. What makes these works “Buddhist Literature” is less determined by an investigation into each work or author’s specific religious makeup, and more determined by the generations of Chinese Buddhist readers who have found wisdom and inspiration in the literature collected within.

The other feature that brings the many works included in After Many Autumns together is the Chinese language itself. Translation necessarily involves making decisions of interpretation, and the translation of After Many Autumns was necessarily complicated and multifaceted. The greatest Chinese poetry is often founded upon its ability to offer poignant ambiguity, and to invest depth of meaning into few characters. Additionally, Chinese Buddhist literature often contends with translation itself, and can be awash in Indic concepts and transliteration. Making decisions regarding how to unpack these ambiguities can be difficult, and the editors of this collection have attempted to follow a moderate path: the goal has been to make the translations sensible to an English reader, while preserving moments of mystery and litheness. When an ambiguous passage can be interpreted in a Buddhist fashion or as plain language, the Buddhist interpretation has prevailed, and explanatory notes provided to explain its significance.

Origins of Buddhism in China

The origins of Buddhism in China are more complex than what is allowed by a single defining moment. Though historical accounts necessarily omit the gradual cultural dissemination of neighboring peoples, the textual accounts of Buddhism’s journey to China have a profound impact on Chinese Buddhism’s self-conception, and most importantly, upon the evolution of Chinese Buddhist literature.

The most popular narrative account of the introduction of Buddhism into China occurs in the Book of the Later Han. The text mentions a dream of Emperor Ming of the Han dynasty in which he sees a vision of a tall golden man. The following morning the emperor asks his ministers if they know of such a man, and is told that to the west, in India, they worship a figure named Buddha that matches such a description. The emperor dispatches an envoy to India in 64 CE to learn more, and his men return with the monks Kasyapa-matanga and Dharmaraksha along with a host of Buddhist relics and texts. These two monks go on to complete the first Chinese translations of the Buddhist sutras, of which only the Sutra in Forty- Two Sections survives today.

Aside from this story there is textual evidence of Buddhists in and around China even earlier. The Records of the Three Kingdoms mentions that by 2 BCE Buddhism was already present in the Bactrian Kingdom to the north, in what is modern-day Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, and that it was gradually spreading towards the Han capital in Luoyang. A Brief Account of the Wei Dynasty’ mentions that a scholar named Jing Lu was taught the Buddhist teachings by the Bactrian envoy Yicun in 130 BCE. This account also mentions various names that Buddhists use to refer to themselves, including Chinese translations of upasaka, sramana, and sravaka, indicating that the Chinese adoption of Buddhist language predated the wholesale translation of the sutras.

Following the arrival of Kasyapa-Matanga and Dharmaraksha, more Buddhist monastics came to China and began the work of translation, creating the earliest Chinese Buddhist literature. Many of these early translations are no longer extant, but notable sutras from this period include the earliest Chinese Dharmapada, translated by Vighna in 224 CE, and the first Chinese Amitabha Sutra, translated by Zhiqian in 228 CEo.

Though not the earliest translator, by far the most significant and celebrated is the fourth century monk Kumarajiva (344-413 CE). Born in the Kucha kingdom, now within modem-day Xinjiang, China, Kumarajiva gained notoriety for his intelligence and scholarship and was eventually brought to China by the Buddhist Emperor Yao Xing to set up a translation center in Changan. As a translator, Kumarajiva was both skillful and prolific, creating translations of the Diamond Sutra, Prajnaparamita Sutra, Vimalakirti Sutra, Lotus Sutra, Amitabha Sutra, and Nagarjuna’s Treatise on the Middle Way, among many others. Kumarajiva’s translations are known for their clear, natural writing, and as such are often still read and chanted today, even if they have been supplanted by later, more precise translations.

Kumarajiva’s translations allowed Chinese Buddhism to grow and diversify, and lead to the founding of Buddhist “schools” or teaching traditions centered around specific texts. For example, Kumarajiva’s translations of the Treatise on the Middle Way, the Treatise in a Hundred Verses, and the Treatise of the Twelve Aspects were introduced to Southern China by Daosheng, leading to Jizang’s founding of the Three Treatise School in the sixth century. Kumarajiva’s translation of the Lotus Sutra became the basis for Zhiyi to found the Tiantai School in the sixth century as well. The importance of Kumarajiva’s translations in creating uniquely Buddhist Chinese idioms and their impact on the aesthetic of later Chinese Buddhist literature cannot be overstated.

| Introduction | xvii | |

| I. PRE-TANG DYNASTY | ||

| 1 | The True Nature of Equality | 4 |

| 2 | Poems on the Four States | 5 |

| 3 | Ten Admonishments | 7 |

| 4 | Faith in Mind | 11 |

| 5 | Do Not Talk of Some one's Shortcomings | 18 |

| 6 | It Is Not Easy to Know People | 20 |

| 7 | Text of One Thousand Characters | 22 |

| II. TANG DYNASTY | ||

| 1 | To Free Oneself from Affliction Is Not Easy | 28 |

| 2 | One Strike and I Forgot All I Knew | 30 |

| 3 | Formless Gatha | 32 |

| 4 | Song of Enlightenment | 35 |

| 5 | Visiting Xiangji Temple | 52 |

| 6 | Thought While Traveling at Night | 54 |

| 7 | Returning at Night to Mount Lumen | 56 |

| 8 | Climbing Mount Xian with Some Friends | 57 |

| 9 | This Ravaged Old Tree Leans in the Cold Forest | 59 |

| 10 | Seeing Off Master Lingche | 61 |

| 11 | All Sentient Beings Gather from the Ten Directions | 63 |

| 12 | Liberation Comes from Not Arguing about True or False | 65 |

| 13 | The Water Is Clear and Limpid | 67 |

| 14 | Eliminating Lowly Words | 69 |

| 15 | The Flower Is Not a Flower. | 71 |

| 16 | A Poem on Swallows to Show Old Man Liu | 72 |

| 17 | Wine Shared Together | 74 |

| 18 | The Spring of White Clouds | 75 |

| 19 | Contemplating the Illusory | 76 |

| 20 | Flowers in a Monastic Courtyard | 77 |

| 21 | Pity the Farmers | 79 |

| 22 | Viewing Mountains with Master Haochu | 81 |

| 23 | Spring South of the Yangze River | 83 |

| 24 | Visiting Chan Master Yaoshan | 85 |

| 25 | Ode to the Wooden Fish and Drum | 87 |

| 26 | Gatha on Transmitting Mind | 89 |

| 27 | Admonishments upon Sending My Son to Leave the Home Life | 91 |

| 28 | Letter of Farewell to My Mother | 94 |

| 29 | Do Not Seek Outside | 99 |

| 30 | Amazing! Amazing! | 100 |

| 31 | The Fragrance of the Lotuses Have Faded, the Green Leaves Have Withered | 102 |

| 32 | How Can We Escape the Sorrows and Regrets of Life? | 104 |

| 33 | For Forty Years My Home and Country | 105 |

| 34 | The Rain Rattles beyond the Curtain | 106 |

| 35 | The Flowers of the Forest Lose Their Spring Red | 107 |

| 36 | Silently, I Climb the Western Tower Alone | 108 |

| 37 | Poem on Condescending to Instruct | 110 |

| 38 | Self Nature | 112 |

| 39 | Inscribed in Nan Zhuang, Outside the Capital | 114 |

| 40 | Unwilling to Leave Through the Empty Door | 116 |

| 41 | Searching for a Sword for Thirty Years | 118 |

| 42 | The Whole Day Spent Looking for Spring but Not Seeing Spring | 120 |

| 43 | Those Who Study the Way Do Not Recognize the Truth | 122 |

| 44 | Living in the Mountains | 124 |

| III. SONG DYNASTY | ||

| 1 | Autumn Thoughts | 128 |

| 2 | Recalling Minchi with My Brother Ziyou | 130 |

| 3 | Written on a Wall in Xilin Temple | 131 |

| 4 | Misty Rain on Mount Lu | 132 |

| 5 | Gatha for Donglin Temple on Mount Lu | 133 |

| 6 | Seeing Off Wang Zili with Water from Bodhisattva Springs in Wuchang | 134 |

| 7 | Recollections of the Red Cliffs | 135 |

| 8 | Composed While Residing at Dinghui Monastery in Huangzhou | 137 |

| 9 | When Does the Bright Moon Appear? | 138 |

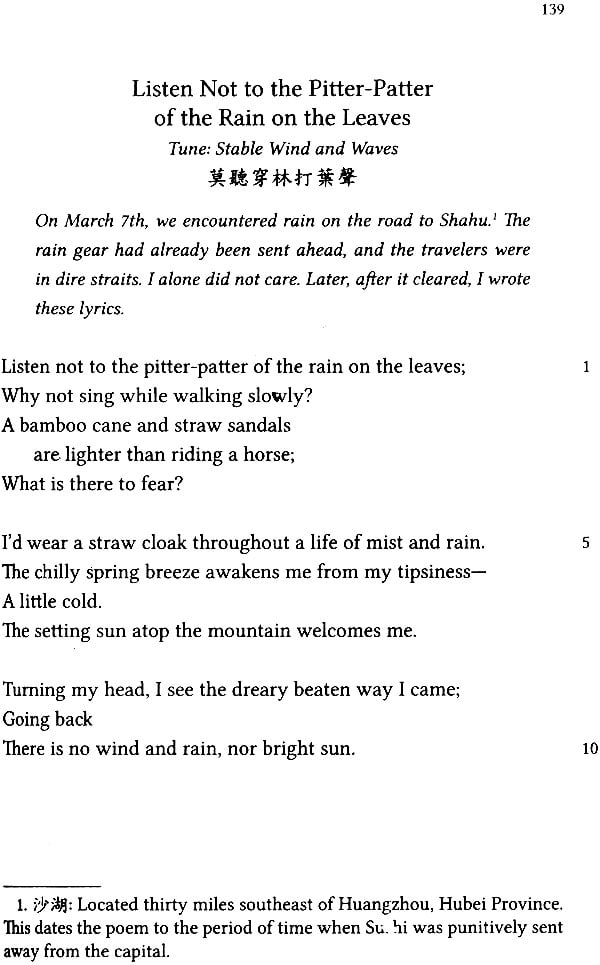

| 10 | Listen Not to the Pitter-Patter of the Rain on the Leaves | 139 |

| 11 | Ten Long Years Obscure the Living from the Dead | 140 |

| 12 | Climbing Feilai Peak | 142 |

| 13 | Yi and Lu Were Two Old Men | 143 |

| 14 | Where Has Spring Gone? | 145 |

| 15 | All the Generals Talked about Obtaining High Rank | 146 |

| 16 | Deep, Deep Is the Courtyard. How Deep? | 148 |

| 17 | Song of Right and Wrong | 150 |

| 18 | Poem in Praise of Coming from the West | 152 |

| 19 | Of the Fallow Field before the Mountain | 154 |

| 20 | Ruiyan Always Said, "Master, Are You Awake?" | 156 |

| 21 | Family Teachings | 158 |

| 22 | Devote Your Mind to Heaven and Earth | 160 |

| 23 | Concerning the One Hundred Foot Pole, I Have Made Progress | 162 |

| 24 | For Love I Seek the Light by Pouring over Books | 163 |

| 25 | At Rest from a Myriad Affairs, Foolishness Takes Over | 165 |

| 26 | When I Practice at Ease | 167 |

| 27 | A Mandarin Duck upon a Pillow, Splendid Curtains | 169 |

| 28 | In the Daodao Forest, the Birds Sing | 171 |

| 29 | When Chuanzi Went Home That Year | 173 |

| 30 | Liberation While Sitting or Dying While Standing | 174 |

| 31 | I Only Travel to Old Places I Have Been | 176 |

| 32 | Undergoing Ten Thousand Things Cannot Compare to One Who Retreats | 177 |

| 33 | Watching the Sky All Day without Lifting One's Head | 179 |

| 34 | Old Juzhi Loved to Teach with One Finger | 181 |

| 35 | Encouraging Cultivation | 183 |

| 36 | I Have a Single Bright Pearl | 185 |

| 37 | A Slip of a Boat on Boundless Waters | 187 |

| 38 | Poems on the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures | 189 |

| 39 | Worldly Affairs Are Short as a Spring Dream | 193 |

| 40 | The Revelry Has Ended, Fragrance Washed Away | 195 |

| 41 | Green Mountains Enjoy Talking with Noblemen | 197 |

| 42 | Night Walk on Yellow Sand Road | 198 |

| 43 | When I Was Young, I Never Tasted Worry | 199 |

| 44 | Too Much! I'm Getting Old! | 200 |

| 45 | To Show My Sons | 203 |

| 46 | Dream Record Sent to Shi Bohun | 204 |

| 47 | The Spring Moon at Night-a Frog Croaks | 206 |

| 48 | Thoughts on Reading | 208 |

| 49 | Passing Dongting | 210 |

| 50 | The Way Is Not in Language | 213 |

| 51 | Where Has the Character for "Worries" Come From? | 215 |

| 52 | Crossing Lingding Sea | 217 |

| 53 | Crossing Wujiang by Boat | 219 |

| 54 | Listening to the Falling Rain | 220 |

| IV. YUAN DYNASTY | ||

| 1 | Epiphany from Cultivation | 224 |

| 2 | Sewing Poem | 226 |

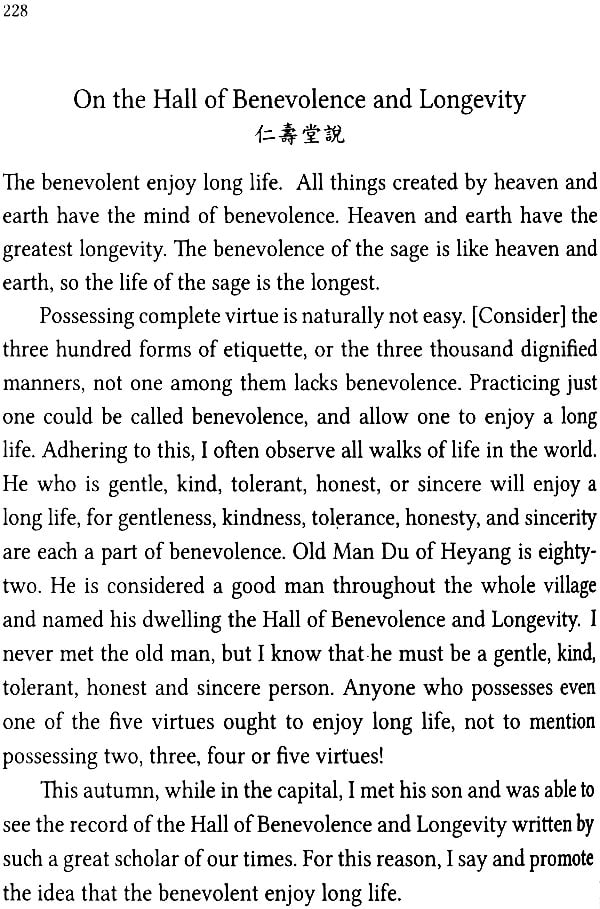

| 3 | On the Hall of Benevolence and Longevity | 228 |

| 4 | Xizhai Pure Land Poems | 230 |

| V. MING DYNASTY | ||

| 1 | Advice for the World | 246 |

| 2 | FourVows | 248 |

| 3 | On the Kitchen | 252 |

| 4 | There Is Water in the Cauldron | 255 |

| 5 | Seven Strokes Across | 257 |

| 6 | Reverent Acts of the Monastics | 261 |

| 7 | The Base Man Projects His Faults on Others | 272 |

| 8 | Treatise on the King of Treasures Samadhi | 274 |

| 9 | Song of a Life | 277 |

| 10 | Rolling, Rolling the Yangze Flows East | 279 |

| 11 | Foundations: Some Admonitions | 281 |

| 12 | Grieve for the Falling Leaves | 284 |

| VI. QING DYNASTY | ||

| 1 | In Praise of Monastics | 288 |

| 2 | Avoiding Meaningless Words | 292 |

| 3 | Baiyun Temple in Minquan County | 294 |

| 4 | Such Thoughts Which Are Unwholesome, Do Not Think of Them | 296 |

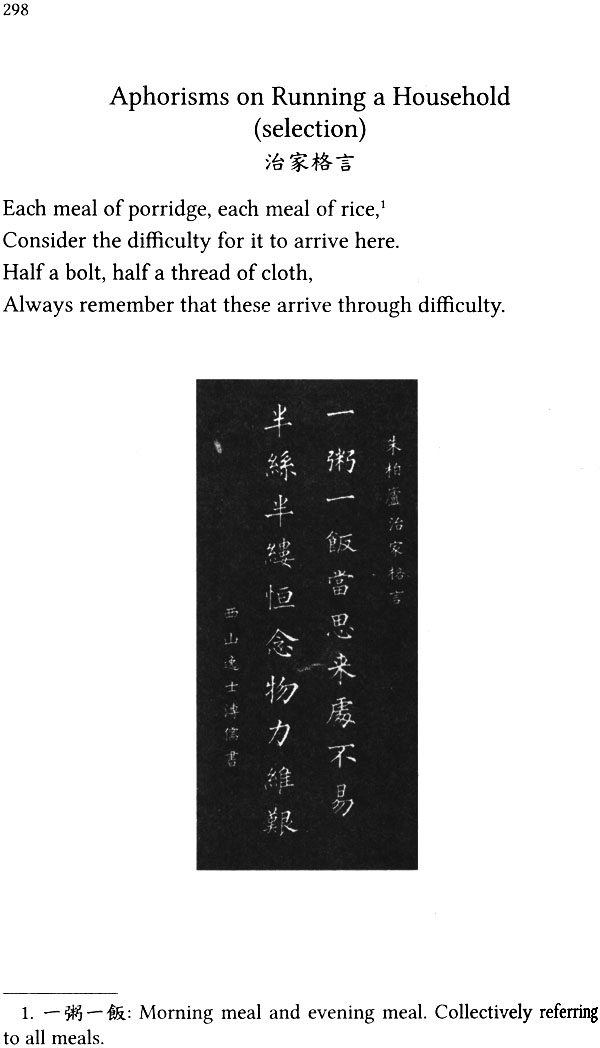

| 5 | Aphorisms on Running a Household | 298 |

| 6 | Do Not Say That One Can Deceive with a Single Thought | 300 |

| 7 | Written on Bamboo and Rock | 302 |

| 8 | One Filled with Pride Is Easy to Damage | 303 |

| 9 | When Someone Speaks of Me | 305 |

| 10 | Exposition on Wealth, Rank, Poverty, and Humility | 307 |

| 11 | Lines Describing Huiju Temple | 309 |

| VII. REPUBLIC OF CHINA | ||

| 1 | True Friendship | 314 |

| 2 | I Do Not Know What It Means to Be a Gentleman | 315 |

| 3 | Thoughts on My Fiftieth Birthday | 317 |

| 4 | Study Is Valuable for Knowing What Is Important. | 319 |

| 5 | Humble Table, Wise Fare | 321 |

| 6 | The Cup Falls to the Ground | 328 |

| 7 | Though Others Do Not Return the Good I Do | 330 |

| 8 | A Letter to Tiaozheng | 332 |

| 9 | Posthumous Admonitions | 334 |

| 10 | Speaking the Dharma, the Blue Lotus of Nine Platforms | 336 |

| 11 | Dharma Words | 338 |

| 12 | VIII. TEMPLE COUPLETS | |

| 1 | Temple Couplets | 341 |

| List of Authors and Calligraphers | 357 | |

| List of Titles and First Lines | 360 | |

| Glossary | 369 |