Analysis of Family Patterns Through a Century (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM068 |

| Author: | H. D. Lakshminarayana |

| Publisher: | Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1968 |

| Pages: | 190 (7 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 260 gm |

Book Description

This work originally submitted as thesis for Ph. D. degree in Poona University aims at an analysis of what has been happening to the traditional Hindu Joint Family at different stages. The study also aims at analysing other important aspects of Hindu Family like-status, authority and work; patterns of marriage and the mode of inheritance and succession. This task would not have been possible but for the keen an untiring guidance of my Professor Dr. (Mrs.) Irawati Karve, for whom I owe a deep debt of gratitbde. I am very grateful to Dr. Y. B. Damle for his timely help, to Mrs. Hemalatha Acharya for her valuable suggestions. Further, I thank my friend Mr. K. C. Malhotra for having gone through the manuscript.

I am also grateful to the authorities of Mysore University for awarding me scholarship, to the authorities of Poona University for grantlng admission, and last but not least to the authorities of Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Poona–6, for all the facilities given during my stay.

Lastly, I thank my friends Mr. G. R. Sundar for his assistance. Mr. Narasanniah for preparing charts, etc. and Mr. M. K. Kulkarni for typing the matter thesis neatly.

I once again acknowledge the help and assistance given by my informants and friends during my study.

Study of Hindu family:

In Hindu Social Organisation, the Caste, the Village, and the Joint Family are in practice interlocked and are regarded as the pillars of Hindu Society from time immemorial. Each works as an undercurrent to strengthen the other. The unit of Hindu Society is not the individual but the joint family. The widest expression of this family is the ‘sub-caste’ which often consists only of a few joint families which inter-marry and inter-dine among themselves (Panikkar, 1955: 18). The joint family is the bed-rock on which the Hindu social organisation is built. It provided an organised life, by establishing a principal of social obedience (Panikkar 1955: 19). In India, the system of the joint family not only persisted but grew in strength during the British period. Mrs. Karve says (1953: 10) , “Neither the Muslim nor the British rule was able to modify the structure of this most ancient institution of India”. This study is an attempt to test the above statement and find what has happened to the family during the last century.

The joint family is a marked feature of the Hindu social organil sation. It has as its main characteristics the idea of a common home for all the members of the family, children, children’s children, and daughters-in-law, all having claims to protection and security. The Hindu joint family is peculiar in that the personal law applicable to Hindu has grown up mainly round this institution.

The joint family system seems to have been the outcome of the ancient rural economy. It has a legal implication, in so far as members of three generations living together and owning certain property in common. “The Hindu joint family, with its heritage, is purely a creation of law, i.e., the social order and cannot be created by the parties save by... adoption. The conception includes a common ancestor. Only al the members of a sub-branch can form a separate corporate unit within the large corporate unit and hold property as such. But such property must arise from self-acquisition or by... unobstructed heritage.” (cf: E. J. Trevelyan, Hindu Family Law, 1908:225).

Sen Gupta says, “The growth of the joint family probably coincided with growing prosperity and the importance of landed property. So long as land was abundant and one had only to settle on new land to start cultivation, as son on marriage went out of the house and set—up for himself. At a later age, when the land could not be had for the asking, the family land would attract the sons and they would and separate so easily. This and other circumstances probably contribu ed to build-up the joint family”. But ‘how far’ says Gupta, ‘this development was the natural result of economic factors and how far it was determined by extraneous influences will never be exactly known’ (N. C. Sen Gupta, The Hindu Joint Family: Appendix in ‘Evolution of law’).

In our society which is predominantly agricultural and rural, the joint family is the system which binds many individuals into a unit of corporate earning and spending. This unit is not static. The historical and sociological factors have influenced this greatly.

In recent days, the impact of science and technology and urbanisation has made inroads into the joint family and a few examples of truly nuclear families occur here and there. As a result there are two divergent views about the age old institution. One section of scholars like Russ (1961) say that the joint family is disintegrating into nuclear or non-joint families, that exist among urbanised and employed class of people. The other section of scholars like Desai (1964), Kapadia (1656) and Agarwala (1955) hold the view that in spite of social and ideological changes, the joint family is intact and inviolable. In between these two viewpoints, there is view expressed by both Indian and foreign scholars like Karve (1963a) and Mandelbaum (1955) that the typical or the classical joint family is not prevalent in these days, and the smaller joint families are the predominant type.

A systematic study of the changes in the joint family was made by Merchant in his assessment of ‘Changing views on Marriage and Family’ (1935). But ever since Mrs. Karve (1953) wrote her ‘Kinship Organisation in India’ many works have been attempted about the joint family in India. Mrs. Karve says: “A joint family is a group of people who generally live under one roof, who eat food cooked at one hearth, who hold property in common and who participate in common family worship and are related to each other as some particular type of kindred.” (1953: 10). This definition characterises the traditional Hindu joint family, which is not in vogue. Although this definition is regarded as a standard definition, ‘essentially this is a structural definition which fits in with the usual definition of the family’ (Owen M. Lynch: 187). Lynch regards this definition as nearer to Murdock’s definition of the family as ‘a social group characterised by common residence, economic cooperation and reproduction’ (Murdock 1949: 1). Yet, Mrs. Karve’s definition strongly suggests the need for cultural as well as structural criteria (Cohn: pp. 1951-55).

Following Mrs. Karve’s work, Desai, Kapadia and Agarwala among some scholars have gone further to work on the definition. Desai subordinates the structure to function by adding common income as well as property, and mutual rights and obligations, that make a joint family (1956: 147–8). Kapadia leans much on the functional aspect of the joint family: ‘On functional basis the residential unit of a person, his wife, and their children do not necessarily constitute a nuclear family (1956: 111–127). Agarwala feels that it is not essential for members of a joint family to live in one place and eat in a common kitchen. What holds a joint family is ‘authority’ (1955: 141–2).

In order to give a minimal definition of a joint family, Bailey writes (1960): “We have to see how people are recruited into a group and what they do together, when we call that group a ‘joint family’”. He mentions a few points as sufficient for a definition:––

(1) Men become members, of joint families by birth, while women who are born into it marry out of it.

(2) Men are coparceners with the rights of ownership and the women are dependents with only the rights of maintenance, except in matrilineal society.

(3) Joint ownership exists among men with regard to the family status.

(4) The joint family is internally divided into nuclear families.

Bailey specifically denies that living under one roof, eating from one hearth, or practising common rituals are necessary for us to regard a group a joint family. “On the other hand, we cannot apply the term ‘joint family’ and still less the term ‘coparcenary’ to those who have no common property.”

Bailey uses the term descent with reference to the made members of the joint family. Descent always refers to the membership of some ‘enduring’ group in which the members always keep in mind the identity of each other. The Hindu joint family is not an enduring group because of successive partition. But what holds the members are the ties of kinship, sentiment, and ritual and moral obligation.

Among Jurists, Mayne (Hindu Law and Usage, 11th edn. :323) writes that :The joint and undivided family is ordinarily joint not only in estate but also in food and worship”. Thus, the presumption is that the members of the joint family are living in a state of union unless the contrary is established. The strength of the presumption of union is stronger in the case of brothers than in the case of cousins, and the further we go from the founder of the family the presumption becomes weaker and weaker.

According to Kane, “A joint family consists of all male members lineally descended from a common male ancestor and includes their wives and unmarried daughters”.

In studying the Hindu joint family, many writers seem to have two criteria in their minds:––

(1) The existence of a familial group larger than the nuclear family and (2) the existence of some property relations. The main reason for confusing the connotation of the term joint family, according to Madan, arises from the failure on the part to the concerned scholars to recognise that there is no necessary connection between the existence of a familial group larger than the nuclear family and the existence of coparcenary rights and obligations among its members (Madan 1962: 22). Madan considers the definition of Mrs. Karve as the standard one. Also, Aileen D. Ross regards the same definition as ‘the most precise’ (1961: 9)

But the definitions of the joint family lead to great difficulties both for comparative and analytical sociology. Lynch asks, “If the family is reduced to a constellation of certain functions, then what is to differentiate it from another social group which, theoretically at least possess the same constellation of functions?” He says that “Such a question reduces observable regularities of structure to a hodge–podge and renders the comparative method worthless.” (pp. 187–8).

Hence, to avoid further confusion about the term ‘joint family’ we can depart to give a picture to the joint family as envisaged in the present study. Accordingly, a joint fomily is one where parents with their married and unmarried sons, and other dependents, if any, live jointly in one residence. Again, a joint family may consist of two or more brother with their wives and children, and perhaps, an older mother. Do such families remain for ever or do they alter in their structure in response to biological, social, economic and other causes has to be answered at this stage?

The joint families have been in the continuous process of formation and fission. Each fission was a starting point of a new joint family, though at the moment of fission it was a non-joint family or nuclear unit (Mandelbaum 1955: 15). This implies a sort of cyclical process in the family structure. Mrs. Karve has evolved a new line of thought in this much discussed problem. She points out (1963a: 701) that joint families alternate between jointness and non-jointness. According to her, between a hundred percent jointness and a hundred percent non-jointness there are a number of families which are ‘semi-joint’. Such ‘semi-joint’ families are those which move to different regions for purpose of employment or business, yet hold a common responsibility at home, and take part in all family functions in the native place, and acknowledge a common authority (1953: 12; 1963a: 701). Thus the tendency to split must be considered in the total context of the group.

| Introduction | 1 | |

| Chapter I: | Analysis of Jointness and Non-Jointness . | 13 |

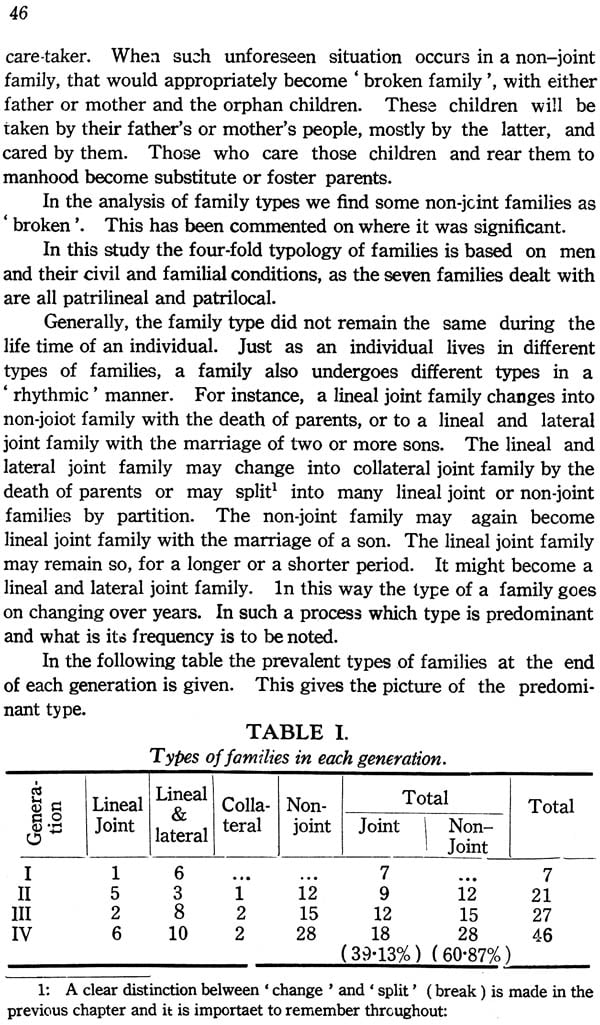

| Chapter II: | Tydes of Familtes and Change. | 45 |

| Chapter III: | Status, Authority and Work. | 70 |

| Chapter IV: | Marriage Patterns with reference to Kinship Marriages. | 79 |

| Chapter V: | Property, Inheritance and Succession. | 119 |

| Conclusion | 140 | |

| Appendices | 157 | |

| Bibliography | 162 |