Buddhist Tantra and Buddhist Art

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDD151 |

| Author: | T. N. MISHRA |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| ISBN: | 9788124601419 |

| Pages: | 132 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| (col.illus.: 12 and b&w.illus.: 4) | |

| Other Details | 9.8" X 7.5" |

Book Description

About the Book:

In (perhaps) secret defiance of the rigid prescriptive codes of the Buddhist monastic order cropped up a new, esoteric cultic phenomenon. Which, later known as Buddhist tantra, not just compromised Sakyamuni's ethical legacy, but came to be administered by a whole host of mudras, mandalas, kriyas, caryas and mysteriously ritualistic elements, even hedonistic practices. Dr. Mishra's book attempts afresh to investigate when, why and how emerged this secrecy-ridden cult: now a spiritual tradition in its own right.

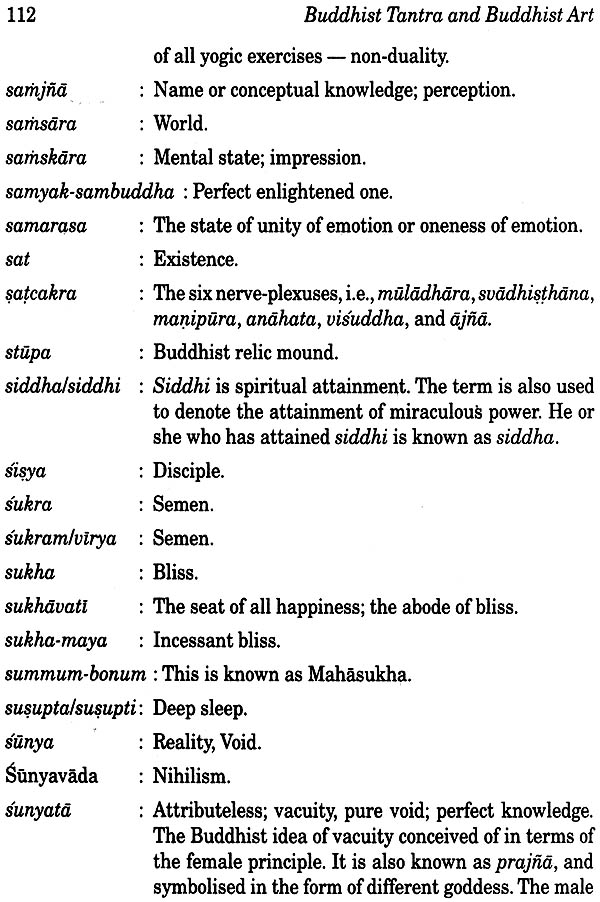

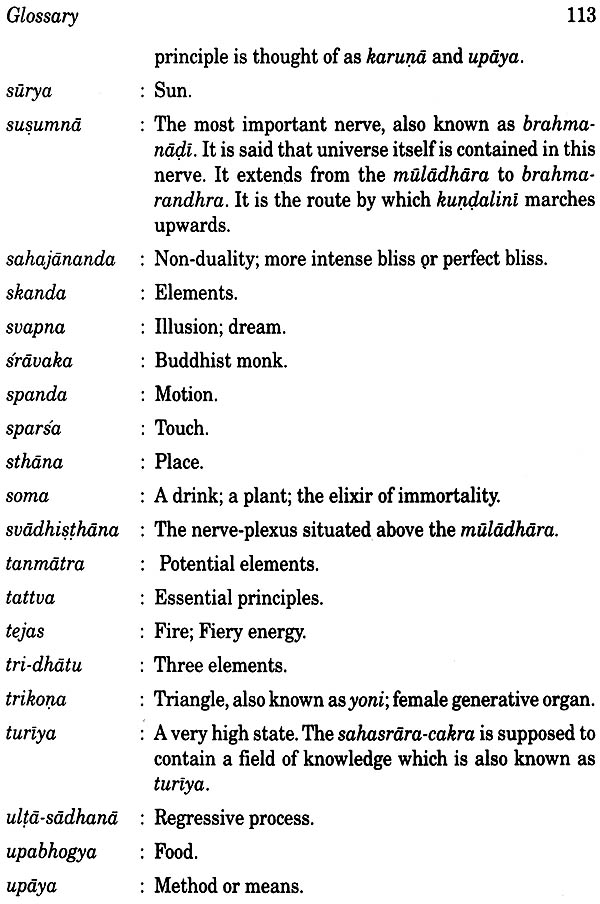

The author, who has had long, personal interactions with some of the living tantriks, here enters the dark alleys of Buddhist tantra to look for its nucleus, its evolution, its culmination, and the causes of its disintegration. Focussing, further, on the shifting philosophical tenets of Buddhism: from Hinayana to Mahayana, Vajrayana, Kalacakrayana and, finally, Sahajayana, Dr. Mishra spells out quintessentially the world-view of Buddhist tantra and its path to nirvana or sukhavati: the abode of bliss, together with a wide range of Tantric concepts that remain guhya (secret) to the uninitiated.

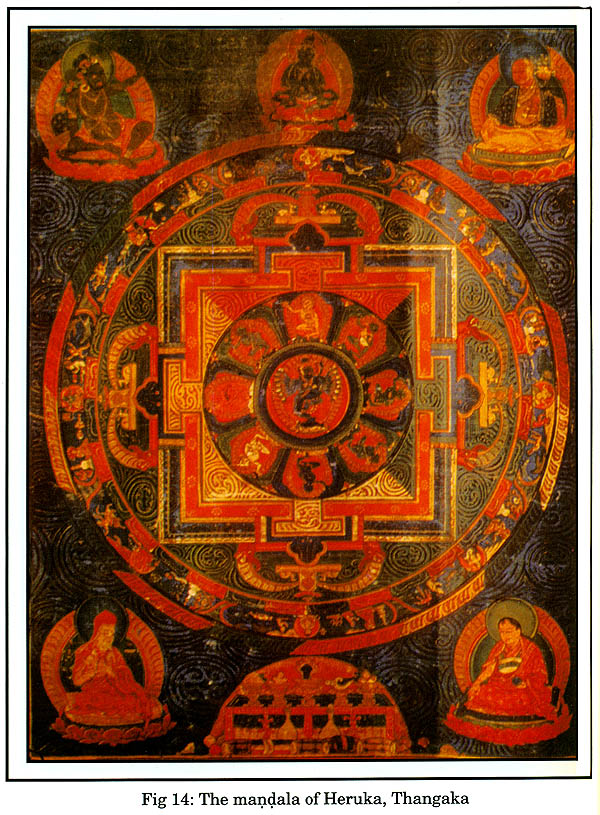

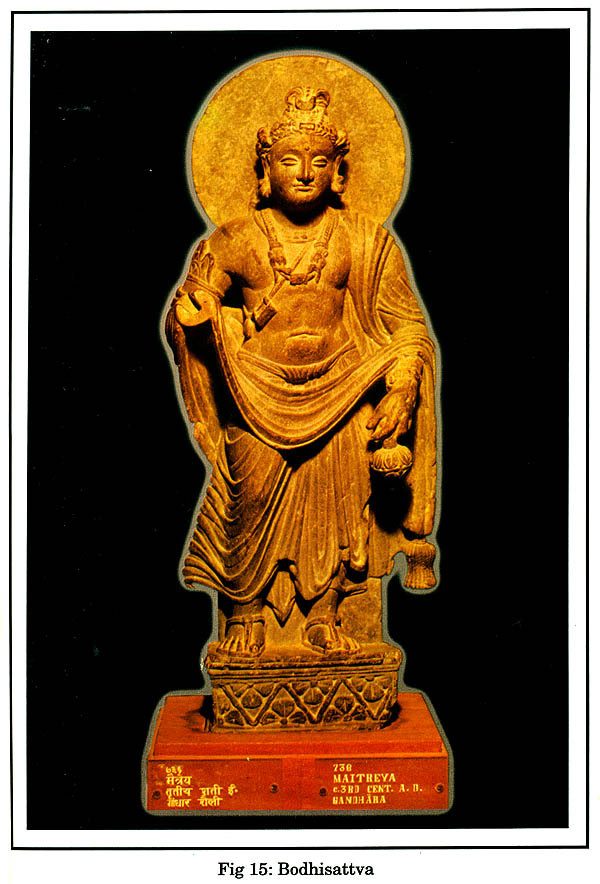

Also showing how Buddhist art, almost from the beginning, has been compellingly influenced by Tantric practices, the book exemplifies the manifestations of this influence in the iconographic representations of the Buddhist deities, illustrated manuscripts, thangkas, and even in the use of colours by the Buddhist artists.

The scholars of Buddhist studies, specially of Buddhist tantra and art, will find the book as both interesting and useful.

About the Author:

T. N. Mishra, a scholar with varied specialized interests, is Assistant Curator, Bharat Kala Bhawan: the prestigious Museum of Art and Archaeology, at the Banaras Hindu University (BHU), Varanasi. Awarded Ph.D., in 1978, by BHU, for his research study on 'Ancient Indian Bricks', he had also taught at two of this university's affiliated colleges, before opting for a career in museology.

Apart from about half-a-dozen books that include Company School of Painting in Varanasi (in Hindi), Westernization of Indian Art, and Impact of Tantra on Religion and Art, Dr. Mishra has published numerous articles in different journals on a range of themes from Indian art and archaeology.

Twenty-five hundred years ago India witnessed an intellectual and religious revolution which culminated in the overthrow of monotheism, priestly selfishness, and the establishment of a synthetic religion, a system of light and thought which was appropriately called dhamma of Buddha. The beauty of Buddhism is that it is a well-regulated and scientific way of life, and not a religion in its narrow sense of spiritualism with dogma and rituals. The Master (Buddha) gave simple and scientific ways for peace, happiness, and ninvana - All this is possible through bhavana.

The word bhavana, used repeatedly in Buddhist scriptures, is a Pali word, and it means culture on mental development. It aims at cleansing mind of impurities and mental disturbances such as lustful desires, hatred, ill-will, indolence, worries, and restlessness. It aims at cultivating qualities like concentration, awareness, intelligence, will, and tranquillity. This mental development ultimately leads one to the attainment of the highest wisdom which would help us in the understanding of nature of things as they are. Buddha gave the world Four Noble Truths - "suffering, origin of suffering, cessation of suffering, and the way to cessation." This, coupled with his Eightfold Path, are key to the success and satiation in this life. Compassion, right action, right livelihood, right efforts, and good intentions are the key words around which Buddhism revolves.

Throughout the history of Indian civilisation, there has been a certain inspiring ideal, a certain motive power, a certain way of looking at life, which cannot be identified with anyone stage of the process. Hinduism has grown not by accretion, but like an organism, undergoing, from time to time, transformations as a whole. It has carried within it much of its early attributes. It is the historic vitality and the abounding energy that, it reveals, helped to sustain its spiritual genius throughout. The unity of Hinduism is not one of an unchanging creed, neither it is a fixed deposit of doctrines, but it evinces a sort of unity of a continuously changing life. Religion is thus an experience and an attitude of the mind, a consciousness about the ultimate reality and is not a theory about the God. The aim of all religions is the realisation of the highest truth. It is the intuition of reality, the insight into truth, contact with the supreme, that form the basic elements of Hindu philosophy. Worship is the acknowledgement of the magnificence of this Supreme Reality. From the beginning, attempts have been made to bring the Supreme Being closer to the needs of man.

The Indian philosophical tradition has been a quest, both for an immediate experience of reality and for an achievement of the good and just life. Men and society have been nourished in India not by ethical and social, but by mystical and trans-social doctrines and ideals. Metaphysics thus becomes the law of man's social living. The Indian ethical system is built on the foundation of metaphysics, certain doctrines, and symbols, and all these invest morality with rich, trans-human meanings. Metaphysics and religion both impart superhuman meanings to the evolutionary process and encourage mankind to evaluate, order, and direct it as frequently as it suffers defeat at the hand of nature. Whosoever feels a universal love for his fellow creatures will rejoice in conferring bliss on them, and thus attaining nirvana on the bliss of his apprehension of non-duality, he overcomes ignorance and sorrow, secures peace, and never suffers degradation. Man reaches his highest moral status when his feeling, joy, and reverence reflect themselves in his relations to the external world through a more sensitive and universalised conscience in terms of a complete acceptance, peace, and an all- transcending compassion or love. Ill-feeling or hatred is essentially self- destructive. Inner calm and altruism, which constitute one level of spiritualism, is good for your own well-being. If you create pain for others, you will suffer and will harm your peace of mind, such is the indispensable contribution of the mystical consciousness to the elevation of moral standards through the discipline of human nature for progress.

In India, a highly well developed civilisation had been flourishing for centuries. Its religious life, in the period between 750 Bc-320 BC displayed certain characteristic features. The first and foremost being the introduction of the images of gods, as worship and meditation of the Supreme Being was thought possible only when He was endowed with a form. There was the belief that the form of the Supreme Being, as He manifests Himself, should be worshipped according to the rites prescribed. The Vedas were considered as the infallible source of spiritual truth, and the rituals prescribed therein, were considered as the sole means of salvation or emancipation. The essential elements common between the two theistic religions, viz., Saivism and Vaisnavism, are bhakti (devotion) and prasada (divine grace). Bhakti means intense love and devotion of the worshipper to his beloved god, even to the extent of complete self-surrender. The prasada means the grace of god which brings salvation to the devotee.

This period was lit up on the other hand by the personality of two great reformers, Mahavira and Gautama Buddha. They were wandering ascetics who ignored god and denied the Vedas, and revolted against the superiority of the brahmanas, There were other people also who criticised the Vedic religion and discarded the Vedas completely and openly. One such person was Carvaka. But the more powerful, systematic, and philosophic challenges were posed by the founders of Jainism and Buddhism. Samkhya and Upanisad served the sources of their inspiration; the gospel of freedom from misery and even the theory of karma (action) were borrowed by them from contemporary religious thought and were systematised by them. Jainism and Buddhism had shared certain common elements philosophically; they both started from the same fundamental principle that the world is full of misery, and the object of religion is to find means of deliverance from the endless cycle of births arid deaths which bring men repeatedly into this world. As karma (action) or an individual action is the root cause of rebirth, emphasis was laid upon conduct and the practice of austerities in varying degrees of severity as the chief means of salvation; and therefore they went against the sacrifice and remained indifferent to prayers to the personal God. Jainism and Buddhism both went for a system of philosophy and social organisation, with a code of morality and cult of their own, which together gave to their followers a sense of religious solidarity.

In the very beginning of early Buddhism, and even when Mahayanism sprang up, a strict discipline was enjoined on the followers of the faith. The rules were indeed very good and attractive at too time of the Buddha but served the purpose only for a certain time but not always. Buddha did not permit the consumption of fish, meat, wine, and association with opposite sex in the church, among other things. The result was that even during the lifetime of the Buddha, many monks are said to have revolted against his injunctions; there were many others who did not openly revolt against the Buddha's injunctions but, nevertheless, violated them in secret. The result was that there arose secret conclaves of Buddhists who, though professing to be monks, violated all rules of morality and discipline and secretly practised what was disapproved by the Buddha and his followers, and disallowed in practice. After the death of the Buddha, such secret conclaves must have grown in numbers, till they formed a school of thought in themselves.

The secret Buddhist conclaves that grew on the ruins of the monastic order developed, in course of time, into big organisations known as Guhyasamaja which held their teachings and practices in secret (guhya). Thus, the Guhya-samaja-tantra was composed in the samgiti form (collection of verses). It explained why the teachings of the school were kept secret for so long, and now even a devout Buddhist could practise all that was enjoined in the Tantra, together with details of theories and practices with rituals. Its most important declaration was that the emancipation does not depend on bodily sufferings and abstinence from all worldly enjoyments. The work lays down that perfection cannot be obtained through the satisfaction of all desires. Its teaching in this respect is direct and unequivocal.

The earlier concept of Buddhism lost itself significantly in the maze of Tantric mysticism in it, and it was practically overwhelmed by the introduction of a host of mudras, mandalas; kriyas, and caryas. Buddhism now began to incorporate elements like magical spells, exorcism, recognition of demons, and female deities (Sakti), and at the same time, yoga and sexo-yogic practices were entertained. All these resulted a significant change and what emerged came to be called Tantric Buddhism. The influence of the Tantric religion and philosophy is found recorded in the religious texts. Texts like Manjusrimulakapa, Saddharmapundarika, Prajnaparamita, Sadhanamala, Nispanna Yogavali, and some other texts incorporated different notions and rituals of Tantra in the Buddhist religion, philosophy, and iconography. The philosophy and religion of Tantra was thus formulated, and in course of time, it made a tremendous impact on the religions. The impact of' Tantric tenets also seeped into the paintings and sculptural art of India.

The introduction of Tantrism affected a radical change in the outlook and character of Indian religion. The high ideals of religion, which aimed at the salvation of all and by the spirit of universal love for all mankind, yielded to gross superstitions and immoral practices so far as the general masses were concerned. Esoteric practices as the easiest means of attaining salvation retarted the growth of spiritual ideas, while the conception of ultimate reality as an embodiment of duality of male and female energy, paved the way for erotic: and sensual practices including the undermining of the sense of moral values. The way advised for salvation was very dangerous for common people; most of them could not succeed and perished on the way. The rational and highly ethical teachings of Buddha were, thus, smoothered under a load of gross superstitions, ritualistic worship of host of deities, and an immoral life against each of which Buddha led a ceaseless crusade.

From the twelfth century onward there was a marked decline in religious practices as also in the field of art. The period from AD 1000 to 1300 was the period of transition, and marked the beginning of the Muslim dominance in India. By the close of this century almost all the important centres of northern Indian Buddhism were affected by Muslim invasions and there began a period of rapid decline. All the communities of India, had to face the disastrous and destructive inroads of Islam which were fired with the fanatic zeal including the demolishing of idols and temples; the intrusion of Islam brought an important change in the religious outlook of India as it introduced for the first time the generic name Hindu. So far Tantric Buddhism was concerned, it turned into a religion of minority some of whom either continued their religious activities secretly while others fled to Nepal or Tibet for the security of their lives and continued their religious activities in an alien atmosphere.

India, the birth-place of Buddhism could not sustain the religion. Buddhism for its esoteric nature lost its touch with lay followers of grassroot level and the final coup de etat was brought into being by Islamic Invasions.

| Acknowledgements | v | |

| List of Illustrations | ix | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| 1. | Religion and Philosophy | 7 |

| 2. | The Development of Buddhist Tantra | 13 |

| 3. | Religious Outlook | 23 |

| 4. | Nath Cult | 53 |

| 5. | Buddhist Art | 65 |

| Plates | 85 | |

| Glossary | 101 | |

| Bibliography | 117 | |

| Index | 125 |