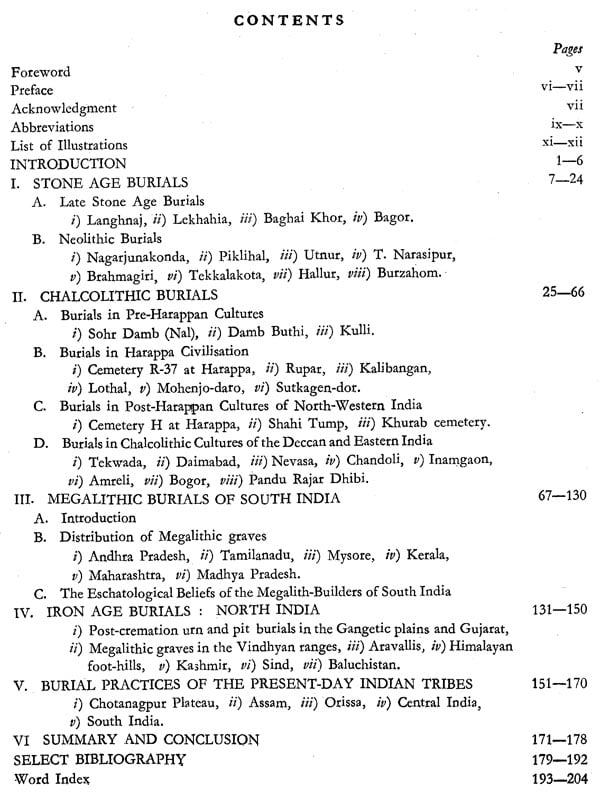

Burial Practices in Ancient India- A Study in the Eschatological Beliefs of Early Man as Revealed by Archaeological Sources (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAZ210 |

| Author: | Purushottam Singh |

| Publisher: | PRITHIVI PRAKASHAN |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1970 |

| Pages: | 204 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 10.00 X 7.50 inch |

| Weight | 680 gm |

Book Description

In the last but one chapter, Purushottam Singh has reviewed the practice regarding the disposal of the dead among the preliterates or the aborigines. For it is still an unsolved problem of Indian Archaeology, who the author: of these Late Stone Age, Chalcolithic and even the Megalithic Cultures are. Such a review would prove extremely useful for planning explorations and excavations in the tribal areas. For it is certain that one has to prove the antiquity of the existence of burial practices, as well as other aspects of life among the tribal themselves. And this cannot be done without proper excavations. Likewise it would be necessary to prove whether the megalithic-looking monuments, for example those near Poona (p. 121), are megaliths, and if so whether they are memorials to the dead, or true burial structures. This alone can prove their antiquity. Very recent work at Theur, near Poona, has shown that what was regarded as a megalithic monument was not so, and the structure whatever it be is not later than 1200 B. C. at the most. Thus the pressing need, as Purushottam Singh has correctly realised, is for more and planned regional curveys and excavations, like the one which Dr. Sundara carried out for the Northern Karnataka on behalf of the Deccan College. In a country like India there are certainly cultural and chronological differences, but these cannot be assumed without a proper investigation. When such investigations are undertaken Dr. Purushottam Singh's book would need revision, as he very modestly says. Meanwhile, the scholars should be grateful to Purushottam Singh for an exhaustive, critical and up-to-date review of the existing evidence for the burial practices in pre- and proto-historic India.

The study of graves is important not only to the archaeologist but to others like anthropologists and social and religious historians alike. Thus while the archaeologist studies the contents of the grave to reconstruct the man's past-in fact the existence of some of the cultures is known by their cemeteries alone-the anthropologist studies the skeletal remains and reconstructs the past races. The social historian classifies the contents of the graves to reconstruct the contemporary social structure. In fact, the Marxist prehistorians have tried to show that changes in funerary ritual are mainly the ideological reflection of changes in kinship organisation and property relations. Thus communal burials in collective tombs would correspond to an economy in which the basic means of production are owned communally by a clan and individual interment would be appropriate to pastoral patriarchal societies (V. Gordon Childe, Progress and Archaeology, pp. 74-75).

The study of the grave-goods throws valuable light on other aspects also. The grave-goods indicate, apart from other things like the material culture and technological advancement of a society, social stratification and the division of labour between either sex. Such a study gives an idea of the economy, mode of living and dress and ornaments of the preliterate societies which have left us little or no historical records. However, in the present dissertation, only the eschatological beliefs of early man have been studied.

The present work forms the thesis submitted to the Banaras Hindu University in 1968 for the degree of Ph.D. My grateful thanks are due to Professor A. K. Narain for supervising this work and for other helps. Dr. K. K. Sinha and Professor S. B. Deo kindly read the type-script and offered valuable suggestions. I am also indebted to Shri B. K. Thapar with whom I discussed several problems. To Professor H. D. Sankalia we are greatly obliged for writing a Foreward to the work at a very short notice. Thanks are also due to Shri P. K. Agrawala, the editor of IC. Series of which the work is No. XVII. We are to thank Shri O. P. Khaneja for preparing the photographs and Shri L. Mishra for drawing the maps.

Archaeological researches for well over a century have brought to light different methods of the disposal of the dead from different parts of the world. While details regarding these methods can be had from the respective excavation reports, some general surveys of these customs have been presented by a number of scholars. Thus the burial customs of ancient Egyptians and their ideas regarding the next world were studied by John Garstang,2 A. Wiede-mann3 and Mercer4 respectively. Greek burial customs have been studied by Robinson.5 Similarly, the archaeological background of the Hebrew-Christian religion has been presented by Jack Finegan.6 The archaeological evidences obtained from different parts of the Old World have been summarized by V. Gordon Childe.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages