The Comparative Phonology of the Boro Garo Languages

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAV907 |

| Author: | U. V. Joseph and Robbins Burling |

| Publisher: | Central Institute Of Indian Languages, Mysore |

| Language: | Boro, Garo and English |

| Edition: | 2006 |

| ISBN: | 817342134X |

| Pages: | 162 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 290 gm |

Book Description

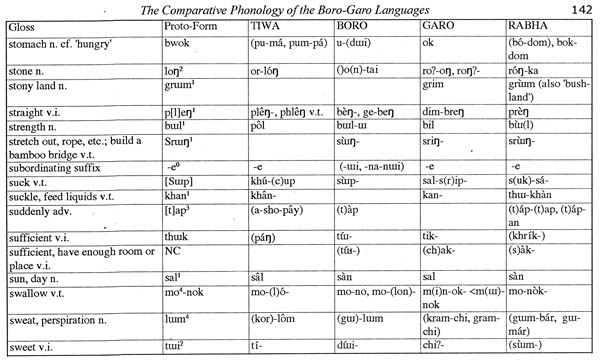

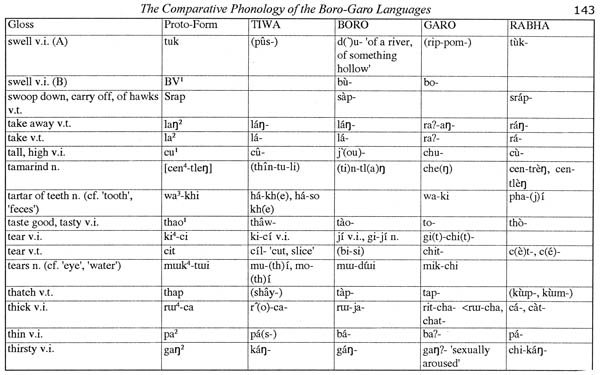

In the life of an institution such as the Central Institute of Indian languages, a time comes after a while when one needs to look back. We believe that the time has now come for us, as we take up serious academic endeavour or coordinate such research activities in this part of the world. We had so far been bringing out only research outputs of scholars from the institute, which is important but which has its own limitations of sheer number and coverage. The Institute enters into a new phase of publication-and information dissemination beginning with January 2006, under which we present to you a comparative-historical study of Tiwa, Boro, Garo, Rabha languages which form a coherent sub- group under the Tibeto-Burman family of languages in South Asia - located by the Brahmaputra valley. As we know, Grierson (1903), in his ‘Specimens of the Bodo, Naga and Kachin groups (LSI, Il. I1Y talks about the sub-family for the first time. Different Koch dialects, Deuri, and Kokborok are the other members that could be added to the list of this group. The Boro-Garo sub-group itself branches into four strands, or sub- sub-groups; (i) A’we, A’beng, Machi, Dual and_ others; (ii) Koch languages including Rabha, Pani Koch, Wa’‘nang, and Tintikia as well as the endangered languages like Mandai, A‘tong and Ruga; (iii) Boro- Kokborok-Tiwa — perhaps including Mech Plains Kachari, and Hills Kachari or Dimasa; and (iv) Deuri. And, it is high time that in-depth studies are undertaken in this area.

Some time ago I had penned the following lines: "...Our linguistics is bound by our languages. It cannot free itself from this chain of ‘impurity’ and uncertainty. It is not surprising, therefore, that ideal speaker- listeners are only a myth that we all like to believe in. All our calculations vis-a- vis speed of learning and rate of retention are only approximations. The way a feature gets diffused through space and time can only be determined roughly. What was once thought to be more exact in linguistics, namely, Phonetics has also turned out to be only approximate and imprecise. Our parsers, built after decades of research, give so many parses that the choice of interpretation as to which one as intended is still left open to listeners or readers." When such is the picture of our discipline, we must slip back to conventional field-based studies — full of hints of exciting processes and rich data. The work presented here is one of the best instances of this kind of study. The present work is obviously built on an earlier attempt to reconstruction work of Burling done in 1959. It has, of course, benefited from several other studies that have been undertaken in the intervening period. The production has had the touches of our editor, Kashyap Mankodi, and this particular activity on a North-Eastern language area has had support from our colleague Rajesh Sachdeva and his team. They as well as the authors, Joseph and Burling deserve kudos.

It is perhaps important to mention here that the Central Institute of Indian Languages was set up on the 17th July, 1969 with a view to assisting and coordinating the development of indian Languages. The Institute was charged with the responsibility of serving as a nucleus to bring together all the research and literary out-put from the various linguistic streams to a common head and narrowing the gap between basic research and developmental research in the fields of languages and linguistics in India. We thought that this task will be unfulfilled if we do not initiate a multi-pronged publication activity under which we bring out the best in South Asian Language Analysis in affordable cost to the reading public and researchers in South Asia. We are hopeful to receive comments and suggestions from linguists and language teachers in this activity. We hope to bring out many more such publications under CIIL’s own series as well as under co-publication brands.

We first met in the cold season in early 1999 when Burling visited Joseph in Umswai in the Karbi Anglong district of Assam. Both _ of us had already had considerable experiences with Boro-Garo languages. Burling had started to learn Garo almost fifty years earlier and he had been exposed briefly to several other languages of the group. He had written a short grammar of Garo (1961) and was working on a more complete grammar, now published, (2004). Joseph had had extensive experience with Rabha, and Boro, as well as with Garo, and by the time we met, he had begun to work on Tiwa as well. His dissertation, a description of Rabha, had been completed (1998) and he was preparing a dictionary of that language, now published, (2000).

Umswai, where we met, is at the heart of Tiwa settlement, and we worked together for a week with a Tiwa consultant. By the end of that week we felt that we understood the Tiwa tones far better than either of us had ever before understood the tones of any Boro-Garo language. We had separately attacked the tones of one or another of these languages, but we worked much better together than either of us had worked alone, so we looked forward to further collaboration. This became possible in December 2000 when, after a second round with Tiwa, we traveled first to Bengtol, Kokrajhar District, in north-western Assam just south of the Bhutan border, to work on Boro. We then went on to Damra near the north-eastern corner of the Garo Hills, where we worked on Rabha. By the time that trip was finished, we were determined to collaborate on a comparative phonology of these four languages. This book is the result of that collaboration.

We have both had extensive experience with Garo, and it is impossible to sort out which parts of the Garo data included here are due to one or the other of us. Joseph’s experience with the other three languages is greater than Burling’s. Most of the correspondences and many of the Garo, Boro and Rabha examples, were included in his dissertation. As we worked together on Tiwa, Rabha and Boro, however, we refined some of Joseph’s earlier findings, and, in particular, much of our understanding of the tone systems of all three languages grew out of our collaboration. Much of the responsibility for the organization and writing up of the results has been Burling’s, but it was always done with regular input from Joseph.

‘One small point of terminology should probably be explained. Burling has long resisted the term "Boro-Garo" as a designation for thissubgroup of languages. He believed that Boro and Garo were closer to each other than either was to Rabha, and that the use of "Bodo" for the group in the Linguistic Survey of India gave that term priority. He is less convinced now than he once was of the close relation of Boro and Garo, and he acknowledges the widespread use of "Boro-Garo" among Tibeto- — Burmanists. He yields to the consensus.

As in any such project, we are both deeply indebted to the hundreds of people who have helped us. This help goes back for fifty years in Burling’s case, and for at least twenty in Joseph’s, but we will limit ourselves here to mentioning, briefly and inadequately, the Tiwa, Boro, and Rabha consultants with whom we worked together. Fabian Malang and Valentine Kholar for Tiwa, Thadeus Basumatary, Isaac Narzary and Sebastian Ishorary for Boro, and Jalam Hato for Rabha. With patience, intelligence, good humour, and curiosity, all of them worked to help us understand how their languages work. We are profoundly indebted to all of them.

**Contents and Sample Pages**