The Gheranda Samhita

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG375 |

| Author: | Srisa Chandra Vasu |

| Publisher: | Dev Publishers and Distributors |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2013 |

| ISBN: | 9789381406205 |

| Pages: | 102 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.0 inch X 5.0 inch |

| Weight | 90 gm |

Book Description

This fine edition of the Gheranda Samhita is a very readable English translation. A seventeenth century classical manual, it speaks of a seven fold yoga and is considered the most detailed of the three classical texts of the Hatha yoga. Gheranda Samhita is a manual of yoga taught by Gheranda to his disciple Chanda Kapali. Unlike other Hatha yoga texts, the Gheranda Samhita speaks of a sevenfold yoga: Shatkarma for purification, Asana for strengthening, Mudra for steadying, Pratyahara for calming, Pranayama for lightness, Dhyana for perception and Samadhi for isolation.

Gheranda Samhita is a Tantrika work, treating of Hatha-Yoga. It consists of a dialogue between the sage Cheranda and an enquirer called Canda Kapali. The book is divided into seven lessons or Chapters and comprises, in all, some three hundred and fifty verses. It closely follows in the foot-steps of the famous trea- tise on Hatha-Yoga, known as Hatha-Yoga Pradipika. In fact, a large number of verses of Cheranda Sarnhita correspond verbatim with those of the Pradipika. It may, therefore, be presumed that one has borrowed from the other, or both have drawn from a common source.

The book teaches Yoga under seven heads or Sadhanas. The first gives directions for the purification of the Body (inside and out). The second relates to Postures, the third to Mudras, the fourth to Pratya-hara, the fifth to Pranayama, the sixth to Dhyana, and the seventh to Samadhi, These are taught successively-a chapter being devoted to each (see Ch. I, v, 9-11).

The theory of Hatha-Yoga, to put it broadly, is that concentration or Samadhi can be attained by purifi- cation of the physical body and certain physical exer- cises. The relation between physical shell (ghata) and mind is so complete and subtle, and their inter-ac- tion is so curious and so much enveloped in mystery, that it is not strange that Hatha-Yogis should have imagined that certain physical training will induce certain mental transformations.

Another explanation-and a later one-is that Hatha-Yoga means the Yoga or union between ha and tha; the ha meaning the sun; and tha the moon; or the union of the Prana and the Apana Vayus. This is also a physical process carried to a higher plane. The first question, which an unprejudiced enquirer WIll naturally put, after perusing this book, will be, are all these things possible? and do these practices pro- duce the result attributed to them?

As to the possibility of these practices, there can be no doubt. They do not violate any anatomical or physiological facts. The practices, some of them at least, may appear revolting and disgusting, but they are not per se impossible. Moreover, many of my read- ers may have come across persons who can practi- cally illustrate these. Such persons are by no means rare in India. Every place of pilgrimage, such as Benares and Allahabad, contains several of them in . , various stages of progress. My own Guru showed me and all his visitors at Allahabad and Meerut several of these processes, and taught some people how to do them themselves. The difficult processes, such as Vari-Sara (Ch. I.17), Agni-Sara (I.20) , Danda-Dhauti (I.37), Vasa-Dhauti (1.40), etc. were all shown by him; so also the various Vastis, Neti, Asanas, etc. Many of these may be classified as gymnastic exercises; their performers need not always be holy or saint-like per- sonages. Several jugglers have been known to per- form various Asanas and Mudras, and earn their livelihood by showing them to the public. For persons whose muscles have become stiffened and the bones hardened by age, the acquirement of several of these postures, etc. is next to impossible; and it is better that they should not court failure or disappointment by attempting these at an advanced age. But Pranayama (regulation of breath), Dharana and Dhyana are possible for all.

As to the utility of these processes, genuine doubts may be entertained. Many of them may appear puer- ile, and, if not positively injurious, at least, useless. Although it is not possible within the short space at my command, to give the rationale of all these prac- tices, and to justify them to a doubting public, yet I shall briefly illustrate the advantages of some of them. Thus, to begin with Vata-sara (1.15). It is the process of filling the stomach with air, and expelling the wind through the posterior passage. The greatest duct or canal in the human body is the alimentary canal, beginning with the oesophagus (throat) and ending with the rectum. It is some twenty-six feet in length. This great drain contains all the rubbish of the body. Nature periodically cleanses it. Yoga practice makes that cleansing thorough and voluntary. If the cleans- ing is incomplete, then the foetid matters putrify in the stomach and intestines, and generate noxious and deleterious gases which cause diseases. Now Vata- siira by passing a current of air through the canal, causes the oxidation of the foetid products of the body; and thus conduces to health, and increases di- gestion. In fact, it gives a tone to the whole system. Similarly, Van-sara is flushing the canal with water, instead of air. It thoroughly purges the whole canal; and does the same work as an aperient or a purga- tive, but with ten times more efficacy and without the injurious effects of these drugs. A person, knowing Vata-sara and Van-sara, stands in no need of purgatives: the same may be said of Bahiskrta Dhauti (1.22). By Agnisara (1.20), the nerves and muscles of the stom- ach are brought under the control of volition; and by the gentle shaking of the stomach and the intestines, these organs lose their lethargy, and act with greater vigour. The washing taught in 1.23, 24, is a little dan- gerous, and may lead to prolapsus, and, a person who can do Vari-sara need not do this. The advantages of cleaning the teeth and the tongue are obvious, and, need not be dilated upon. The lengthening of the tongue (1.32) is necessary for performing hyber-na- tion. In doing this, man but imitates the lower crea- tion, like frogs, ete. who in hybernating turn their tongues upward, closing the respiratory passage. Per- haps, the most interesting of all Dhautis is the Vasa- Dhauti (1.41), which has led unobservant persons to the belief that the Yogis can br.ing out the intestines by the mouth, wash them, and then swallowing them again place them in their proper position. This Dhauti is, however, a very simple process, and by so doing the mucus, phlegm, ete. adhering to the sides of the alimentary canal are removed. Water and air could not remove these viscid substances that stick to the sides of the canal.

| Foreword | ix | |

| Lesson 1 | On the Training of The Physical Body | 1 |

| Lesson 2 | The Asanas, or Postures | 16 |

| Lesson 3 | On Mudras | 29 |

| Lesson 4 | Pratyahara, or Restraining the Mind | 52 |

| Lesson 5 | Pranayama or Restraint of Breath | 54 |

| Lesson 6 | Dhyana-Yoga | 75 |

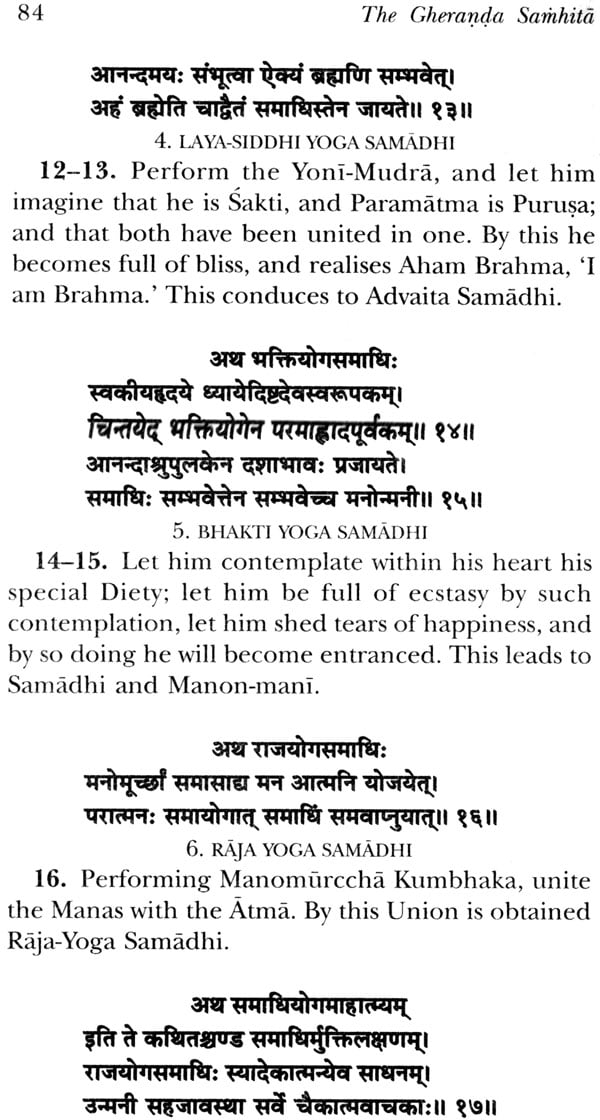

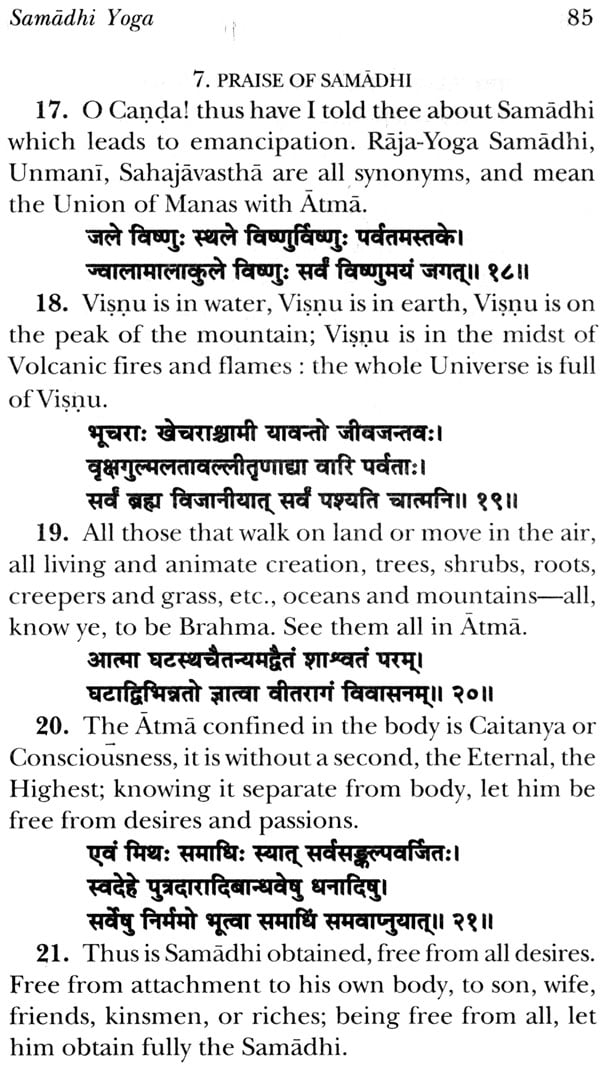

| Lesson 7 | Samadhi Yoga | 81 |