Interpretations of Ancient Indian Polity : A Historiographical Study

Book Specification

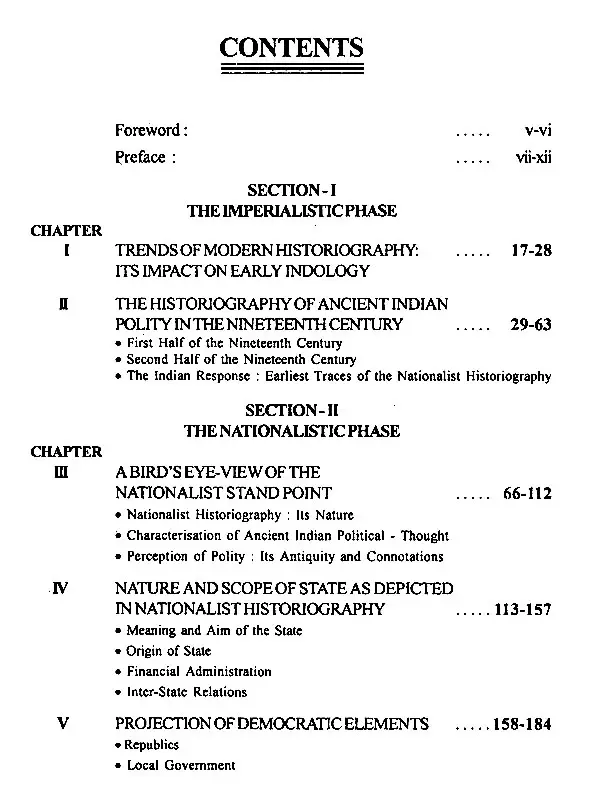

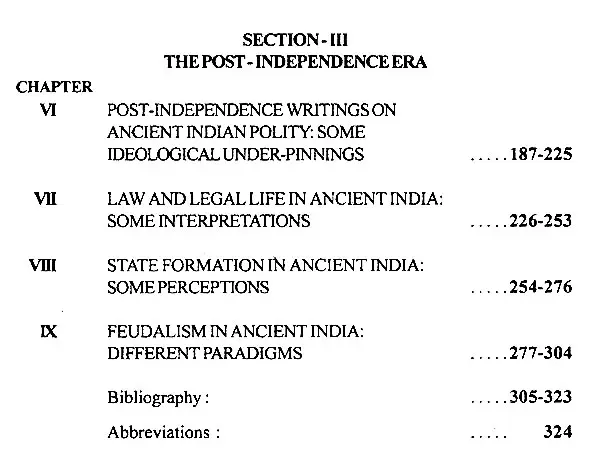

| Item Code: | UAE085 |

| Author: | Dinesh Kumar Ojha |

| Publisher: | Manish Prakashan, Varanasi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2006 |

| ISBN: | 8190246968 |

| Pages: | 323 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 540 gm |

Book Description

This book traverses the long and varied paths and lanes of the genesis, growth and development of Historiography of Ancient Indian polity. It analyses the political, social and ideological factors behind the growth and ramifications of various schools of historical interpretations in the field, including the Imperialistic, the Nationalistic and the Marxist, highlighting different sub-schools and persuasions within each of them. On this score the book is a novel attempt in a field that has remained more or less a virgin territory.

Dr. Dinesh Kumar Ojha was born and brought up at Allahabad. He did his M.A. in Ancient History from Allahabad University and was awarded the Degree of D. Phil. from the same Institution in 2002. Having a brilliant academic career throughout, he is presently Lecturer in the Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi.

Analytical study of historical writings is a fascinating subject. Historians through their writings not only reveal the past, but also reveal themselves and their own times. As the discipline of history is becoming more and more interpretative, it is mom and more reflecting the concerns of the historian and the historian's age. A major trait of the modem age has been the expansion of the domain of politics; politics is now perceived to be colouring, conditioning and governing practically all aspects of human life and activities. There-fore, when the historian takes up such an overtly political theme as the study of polity, he is more apt to be caught in the crosscurrents of political interests. In the case of Indian history the possibility of the entrance of political interests and ideologies was further facilitated by the combination of certain additional factors. The discipline of history in the modern sense had no past tradition of its own in this country. It was a discipline planted on a virgin soil, as it were, and nurtured by the Westerners who had obvious and strong political interests and civilizational attitudes. By and large it was not easy for the Western historians of India to adopt equanimity in dealing with India's past. Civlizational and political interests often bred prejudices in their outlook. Than the discipline of history took its birth in the country with prejudice imprinted on it as a part of its personality. The first generation of indigenous historians in their mm often consciously endeavoured to redress the balance. Then, in the wake of Independence the feeling gradually started sinking among our countrymen that after a long denial here was now a chance to share power and participate in the governance of the country. This led to an increasing politicization of all walks of life. This had its impact on the practice of history. Dr. Dinesh Ojha in the present work has undertaken the task of sketching some of these background factors that played interesting parts in the formation of the historians outlook and the repertoire of their interpretation-kitbag. It is an interesting and valuable area that he has chosen. He deserves our unstinted praise for the undertaking. In his study he has shed important light on some aspects of the growth of the discipline of history in our country. The present work in many respects is a pioneering venture. We hope that Dr. Ojha will continue his work in the field and enrich our understanding of the practice of history in the country: We further hope that his work will inspire other scholars to undertake similar studies.

Renaissance and reformation, changed the world view of the Europeans. Religion lost its central position and the past was analysed in a critical manner. The belief in the 'dignity of man' and a 'mechanistic interpretation of the universe', heralded a new era of studies in Humanism and advances in Science. Humanism as a programme of studies, replaced the medieval emphasis on logic and metaphysics with the study of language, literature, history and ethics. History in this age not only became secular, non-partisan, instructive and rational but also acquired broader horizon in 'space and time'. Voltaire accusing the narrowness of universal history brought into the fold of the past, India, China and Islamic world, on account of their antiquity and high level of culture.

For most of the Europeans, 'Indians of antiquity had no sense of history', was like an axiomatic truth. It was generally assumed, that Indians were no much engrossed in religious and metaphysical speculations, that they had no interest in studying and analysing the mundane affairs of the world. But such a monolithic interpretation about the culture and tradition of India did not go unopposed, right from the beginning. 'Indians were a nation of philosophers'; the famous dictum of Max Muller was challenged by scholars like Hopkins and Rhys Davids. Hopkins did not subscribe to the view point that Indians were too much religious. He observes, 'our earliest literature is indeed religious, though with but little mysticism. But the religious elements did not penetrate deeply into un priestly classes'.

History, if defined as a scientific record of unique events or an inquiry into the past with the logical purpose of explaining its causes and consequences, Indians can be said to be ignorant of it. e But, if the views of Voltaire, who says, history is neither the story of the kings nor of their deeds but the manners of the people, the mood of the age and the spirit of the times, is taken to be correct, then Indians certainly had a history of their own. The vast mass of ancient Indian literature, the archaeological materials, accounts of foreigners and the floating myths and legends, if analysed dispassionately and critically, are but reliable sources of knowing the past of India.

Even though, the writing on the culture, religion and philosophy of ancient India began with the establishment of Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784, earliest speculations about the polity of early India, cannot be traced before the first quarter of the nineteenth century. However, the needed impetus could be achieved only after the revolt of 1857; when the scholars began to study the polity and political thought of ancient India on the basis of various Dharmasutras and Epics. But it was only with the emergence of the nationalist school of historians that the study of ancient Indian polity came to acquire the status of central theme. The first half of the twentieth century was the period when the most extensive and in depth analysis of the political organisation in early India was undertaken.

The nature of polity and political ideas, as existing in ancient India, does not form the subject matter of this book. Instead, an attempt has been made to understand how different scholars have perceived the polity of early India. The way these issues were looked upon by modem historians and the differences in their views, constitute the kernel of this work. Every historian is a product of his age. Like any other individual a historian too is influenced by the socio-economic environment he lives in. The views, the notions and the prejudices of a historian, undoubtedly come into play, whenever he tries to reconstruct the past. In the course of my study, I have endeavoured to analyse those factors, which affected different perceptions about the political ideas and institutions.

An attempt to fathom the intellectual achievements of the last two centuries would tantamount to a journey which unravels the making of modem mind. While commenting upon the past deeds and behaviours, a historian, inadvertently reflects his own feelings and assumptions, his thoughts and premises. The thoughts and assumptions of a historian, on its part, are functionally related to the socio-economic reality of his surroundings. This is mom aptly brought to fore by E.H. Carr when he observes' when we attempt to answer the question, What is history?, our answer consciously or unconsciously, reflects our own position in time, and forms part of our answer to the broader question, what view we take of the society in which we live'. Thus, it follows as a natural corollary that the writings and observations of the imperialist historians, would reflect the then prevailing mindset of the Europeans, more importantly the Britishers; whereas the views of nationalist historians of the twentieth century are but a commentary upon the hopes and aspirations of the Indian masses, who at that time were overwhelmed by the national movement.

The historiography of ancient Indian polity has, in the course of its development, passed through different stages. In its initial stage, the so called imperialistic phase dominated the scene. This was followed by the nationalist and the Marxist phase of history writing. What were the differences and similarities between these schools of thought? what were the factors which facilitated the transition of one phase into another? what was the impact of colonialism-national movement in history writing? - are some of the questions, which am sought to be answered. A historian, more often than not, indulges in rationalizing the present and sometimes, even plays to the tune of politicians and administrators. Thus, it appears that the historical necessity, which compelled the imperialist historians to condemn the society and culture of India, was the intellectual justification for the colonialism. Similarly the nationalist scholars eulogised the past of India, mainly because it helped in regenerating the pride and self confidence of Indians and thus gave a boost to the national struggle.