Love and Sympathy in Theravada Buddhism

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDC236 |

| Author: | Harvey B. Aronson |

| Publisher: | Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1999 |

| ISBN: | 8120814037 |

| Pages: | 136 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5" x 5.5" |

| Weight | 190 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

Love and Sympathy in Theravada Buddhism discuses the context and contents of the Theravada teachings on love, sympathy, and the collective meditative set of four sublime attitudes (brahmavihara)- universal love, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. The presentation is based upon the first four of the five collections of Buddha's discourses, a stylistically homogeneous compilation of the earliest strata of Theravada scripture compiled before 350 B.C.

After discussing the Pali material relevant to these topics in the first five chapters of this work, the author includes a detailed examination and critique of their position in Chapter Six. His concern is with the motives to social action as well as the psychological and soteriological import of the Theravada teachings on love, sympathy, and the sublime attitudes. Only through seeing these Theravada Buddhism be appreciated.

Preface

This work has its earliest roots in my study of works on religious love by Soren Kierkegaard and Martin Buber. A lecture by Dr. Richard Alpert made me aware of complementary material on this and related topics in the Asian religious traditions. My interests eventually became focused on Buddhism under the formal instruction of the graduate faculty at the university of Wisconsin, Madison. There I was guided by Professors Stephan Beyer, Minoru Kiyota, Khentsur Rinbochay Ngawang Legden, Arthur Link, Robert Miller, A.K. Narain, Usha Nilsson, Geshe Lhundup Sopa, and Frances Wilson in the preparations necessary for undertaking this work. I am saddened that my mentor Professor Richard H. Robinson could not live to see this, the revision of my doctoral dissertation, in print. His encouragement to do field work led me to India where my appreciation of Buddhism deepened significantly.

I am grateful to the government of India for allowing me to be a visiting scholar in their country where I was able to complete the initial phases of this study. I am especially indebted to the American Institute of Indian Studies, New Delhi, which arranged and supported my stay in India. At the Institute, Professor Robert Miller and Mr. P.R. Mehendiratta were solicitous of my every need. They arranged for my work to be directed by the kind and helpful Professor Jagannath Upadhyaya of Varanaseya Sanskrit Vishvavidyalaya.

In India Elizabeth Napper informed me about the Theravada meditation teacher Satyanarayan Goenka-jii and for this I am most grateful. Goenka-jii patiently and joyfully opened my eyes to the riches of Theravada Buddhism. My appreciation of his teachings has been deepened by my contacts with John Coleman and Robert Hover. In addition I am grateful to Mrs. Nina Van Gorkom whose instructions on the Theravada analysis of phenomena revealed connections between theory and practice formerly overlooked. Professor Donald Swearer's work on modern Theravada helped focus my concerns in Theravada psychology and ethics. Though I have not met the authors, my study of Theravada has been most influenced by the clear and stimulating works of Ledi Sayadaw, Nanamoli Thera, Nyana-ponika Thera, and Buddhadasa Bhikkhu.

This work would not have been possible without the assistance of the University of Virginia Alderman Library, especially its Interlibrary Loan staff and the altruistic South Asia Bibliographer, Richard Martin. Comments on this study by my colleagues Professors John Roberts and Seshagiri Rao were most beneficial. The findings have been tested and tempered through extensive discussion with Professor David Little whose probing questions helped me formulate the overall analytical framework for this presentation, particularly the last chapter. The encouragement and editorial advice offered by Professor Jeffrey Hopkins during the latter stages of this project is deeply appreciated. The University of Virginia has been most generous in defraying the secretarial expenses incurred during the final preparation of this work.

I would like to thank my friends Davis Dillon and Professor Natalie Maxwell for the fruitful discussion we had on the issues involved in this work, and Leah Zahler and Don Lopez for their stylistic suggestion. Allen and Patsy Howard were most kind to design the book jacket. Finally, I am grateful to Anne C. Klein for her inspiring and sustaining companionship during the wonder filled years in which this work was bring completed.

Quotations from Winston King's, In the Hope of Nibbana are used by permission of Open Court Publishing company; from Melford Spiro's Buddhism and Society, by permission of Harper and Row, Publishers. The Buddha on the cover is from the Munsterberg collection and is reproduced with the permission of Hugo Munsterberg, New Paltz, New York.

This study was made possible by all those mentioned above as well as the countless individuals who have preserved the Theravada tradition over numerous centuries. I hope that I have done justice to that tradition and that those who read this work will benefit.

Introduction

In the Theravada Buddhist discourses Gotama Buddha often tells the monks to cultivate love (metta), or to act out of sympathy (anukampa). Our immediate reaction might be that the highest expression of sympathy is to aid others' material well-being, but our esteem for material assistance presupposes that a person has only one life to live and thus our main concern should be to make it pleasurable. Gotama, however, taught that we are actually trapped in a beginningless continuum of rebirth perpetually re-experiencing the sufferings of birth, old age, sickness, and death. He also taught that the escape from this entrapment is the immortal state called nirvana. His and his disciples' teachings which show the way to end suffering and attain this immortal state are an expression of sympathy for the plight of the world.

This book discusses the context and contents of the Theravada teachings on love, sympathy, and the collective meditative set of four sublime attitudes (brahma-vihara) universal love, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. The presentation is based upon the first four of the five collections of Buddha's discourses, a stylistically homogeneous compilation of the earliest strata of Theravada scripture compiled before 350 B.C. These come to sixteen volumes in Pali and contain a representative sample of Gotama's teachings on love, sympathy, and the four sublime attitudes. The related Theravada commentaries are examined. Compiled and translated from Sinhalese into Pali by Buddhaghosa in the fifth century A.D., these texts were composed in India during the first two centuries after Gotama and in Ceylon between the third century B.C. and the second century A.D. Since the Sinhalese works upon which Buddhaghosa based his collection no longer exist, his commentaries are the major source for understanding the elaborate system that constitutes Theravada Buddhism. (Unless otherwise noted, all commentaries mentioned in this work are those collected and translated by Buddhaghosa). Of prime importance also is Buddhaghosa's The Path of Purification (Visuddhimagga), the earliest thorough explanation of the Theravada system of philosophy, ethics, psychology, and practice extant in Pali.

Traditionally, monks expressed their sympathy to laypeople through education at the village level. This has been replaced to a large extent by modern Christian or state schools. Further-more, that traditional education, with its emphasis on Pali, Sanskrit, cultural history, and so forth, has little application in civil-service or business careers. Thus, the monastic educational system has lost its appeal and fallen into eclipse, with the result that a pressing problem facing the Buddhist monastic community today is the revitalization of its expression of sympathy for others.

Two modern Western scholars, Winston King and Melford Spiro, have asserted that the normative ethic of Theravada Buddhism is one of withdrawal from society and abstention from social involvement. According to King and Spiro's view, the current situation of diminished monastic social involvement reflects a supposed ethical norm established in the discourses and their commentaries. However, a rigorous analysis of the specific instructions on social concern namely, the teachings on love, sympathy, and the sublime attitudes indicates this is not the case. Furthermore, the historical records indicate that up to the modern period the Buddhist monastic community has been actively involved in improving the community life of the societies where it has flourished. Still, King and Spiro's characterization has achieved such widespread currency and acceptance that many in the West consider it the orthodox interpretation of Theravada ethics. However, since neither King nor Spiro works in Pali, neither has done the close textual and commentarial work necessary to support their theory. Therefore, after discussing the Pali material relevant to these topics in the first five chapters of this work, I have included a detailed examination and critique of their position in Chapter Six. My concern is with the motives to social action as well as the psychological and soteriological import of the Theravada teachings of love, sympathy, and the sublime attitudes. Only through seeing these facets can the unique vision of Theravada Buddhism be appreciated.

About the Author

Harvey B. Aronson, Ph.D. (Wisconsin, 1975), is currently an Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, specializing in Buddhism, at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Under the auspices of the American Institute of Indian Studies, he spent two years in India (1971-1972) studying the philosophy and meditation of Theravada, Mahayana, and Tantric Buddhism.

Extracts from reviews:

"... the present book makes an attempt-based on the early Pali discourses of Buddha-to show that the concern for others, or love and sympathy for them is very central to Theravada religious life.

The book comprises six chapters. In these chapters the book discusses the context and content of the Theravada teachings on love, sympathy, and the collective meditative set of four sublime attitudes-universal love, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity. The source for this study is the first four of the five collections of Buddha's discourses."

| Preface | vii | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| Chapter One : | Buddha's Sympathy | 3 |

| Timeliness of Buddha's sympathy | 8 | |

| Receiving gifts out of sympathy | 9 | |

| Chapter Two : | Disciples' Sympathy | 11 |

| Teaching others out of Sympathy | 14 | |

| Sympathy and Practice | 17 | |

| Sympathy as Antidote | 18 | |

| Simple Compassion and its Function | 22 | |

| Chapter Three : | Loving | 24 |

| The Loving Mind | 24 | |

| The Loving Mind in Absorption | 28 | |

| The Bodhisattva's Loving Mind | 30 | |

| Disciples' Loving Activities | 31 | |

| Instructions to practice Loving Activities | 34 | |

| Beneficiaries of Loving Activities | 37 | |

| Chapter Four : | Love | 39 |

| Acts of Love toward the Teacher | 39 | |

| Love and Anger | 40 | |

| The Power of Love | 48 | |

| Benefit of Love | 56 | |

| Chapter Five : | The Sublime Attitudes | 60 |

| Order of Development | 69 | |

| Faults of the Sublime Attitudes | 71 | |

| Gotama's Love, Compassion, Sympathetic Joy, and Equanimity | 73 | |

| Insight and the Sublime Attitudes | 74 | |

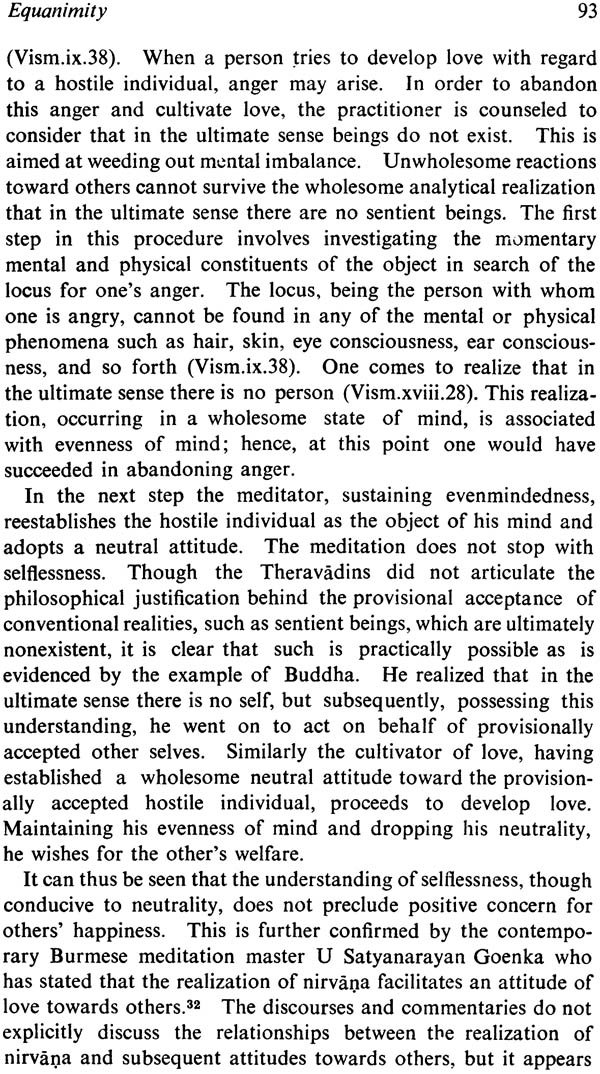

| Chapter Six : | Equanimity | 78 |

| Scriptural Description of a Fully Liberated Being | 85 | |

| Separate Meanings | 86 | |

| Detachment or Concern | 94 | |

| Note on References | 97 | |

| Notes | 98 | |

| Bibliography | 111 | |

| English-Pali Glossary | 117 | |

| Proper Names and Discourses | 124 | |

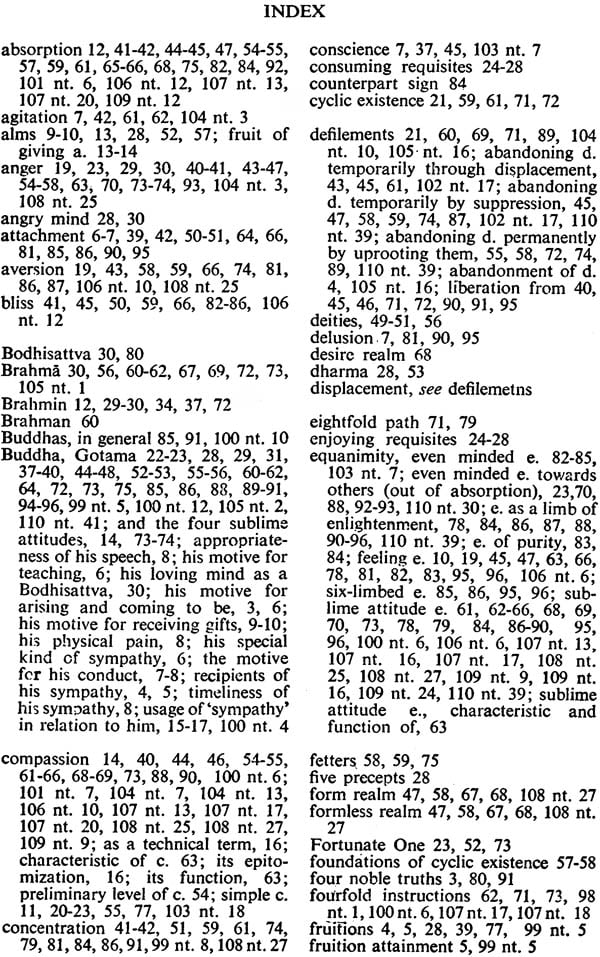

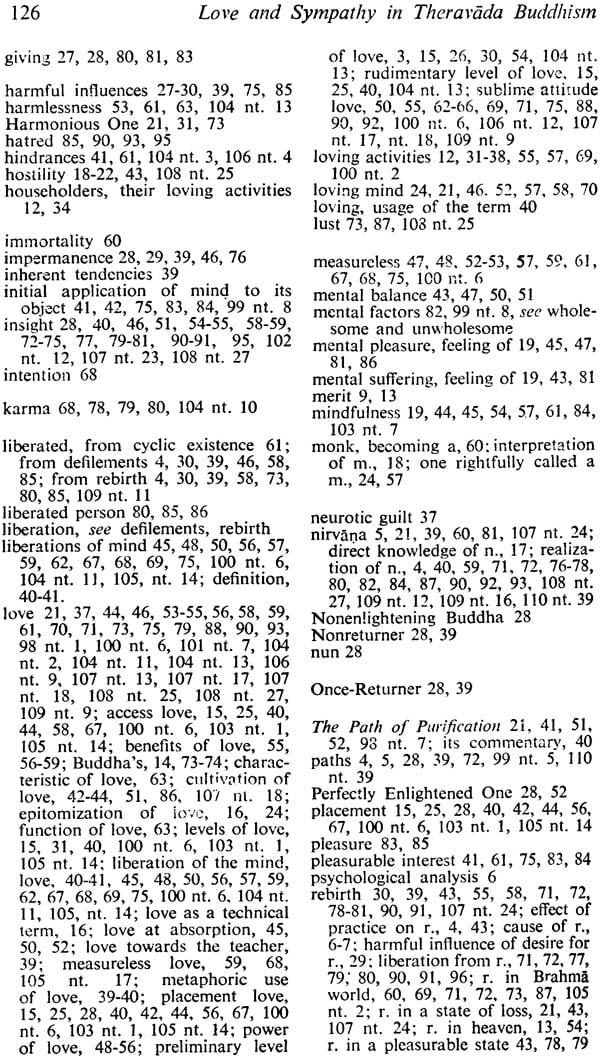

| Index | 125 |