The Miiror of Composition (A Treatise on Poetical Criticism Being an English Translation of The Sahitya-Darpana of Viswanatha Kaviraja)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAH856 |

| Author: | J.R. Ballantyne, Pramada-Dasa Mitra |

| Publisher: | Shiv Books International, Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2005 |

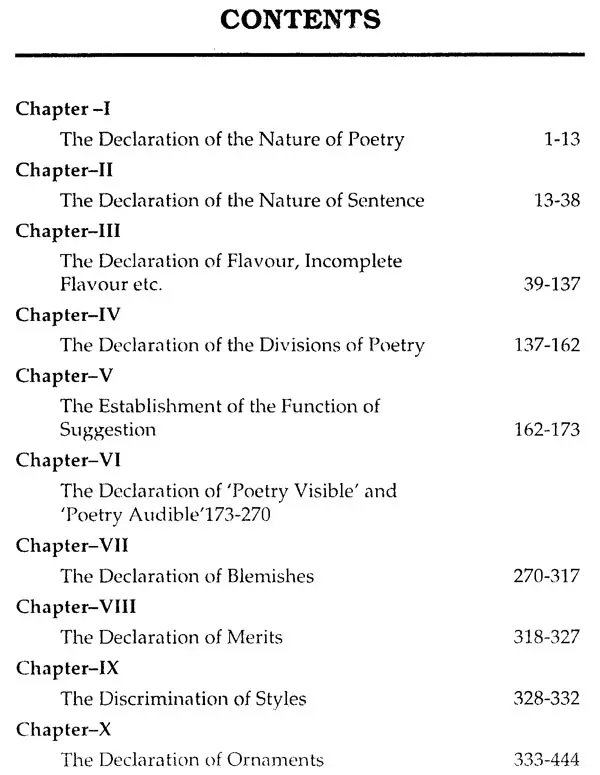

| Pages: | 460 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 650 gm |

Book Description

of the etymology of the term Sahitya two explanations are offered. According to the one, it is derived from hita benefit and saha with." because a knowledge of it is beneficial in all departments of literature. The other, with lens appearance of reason, explains it as denoting the sum total of the various sections of which the system itself is made up.

The term Rhetoric as employed to denote the subject of a treatise of this description, is liable-according to our view of the division and denomination of the sciences, to an objection the converse of that to which we hold the term Logic liable: when employed to denote the all embracing sphere of the Nyaya philosophy. In the Sahitya we have but a part and the least important part of what, according to Aristotle. belongs to Rhetoric. In order to attain its specific end of convincing or persuading between which we agree with Mr. Smart in thinking that there is more of a distinction than a difference-Rhetoric does not hesitate to avail itself of the grease of language which gratify the taste but in the Sahitya, "taste" (rasa) is all in all. The difference between the political history of India and that of Greece or Rome so obviously suggests the reason why eloquence, in the two cases, prosed to itself ends thus different, that it would be idle to do motre, than allude it in passing.

I should think it is the most unpoetical expression that could be used to denote the soul of poetry.

Our author, I think, has furnished a very apt definition of Poetry, viz., 'A sentence the soul whereof is Relish.' Now the question arises—What is it that constitutes relish itself? It is pleasure no doubt, but not the sort of pleasure which is felt, for instance, from hearing such words as simply convey a gratifying intelligence. It is a peculiar pleasure, it is a passion or emotion, it is love, or sorrow, or mirth, or wrath, or magnanimity, or terror, or wonder, or even disgust, or it may be pure and passionless joy, *—not excited by its ordinary causes but delightfully suggested by a representation of what are its causes, effects, and concomitant mental and bodily states in the theatre of life. These, as exhibited in Poetry, are respectively called Excitants (vibhava), Ensuants (anubhava) and Accessories (vyabhichari); and a combination of these, whether wholly expressed, or partially expressed and partially implied, developing the nine modes of sentiment mentioned above, constitutes Poetry which has thus a nine-fold character It is clear from the above elucidation that the Indian Critics held the right view, that an exhibition of human passion or emotion alone is poetry Where, it might at first be objected, is the element of passion in the description of inanimate nature, or of irrational creatures? A little reflection would show that, in order to be poetical, it must have the colouring of emotion; it must, to use Indian phraseology, call forth one of the permanent sentiments by an exhibition of a part at least of the three-fold cause of its manifestation. Thus, the Sublime and the Beautiful in nature must some under one or other of the Relishes enumerated.

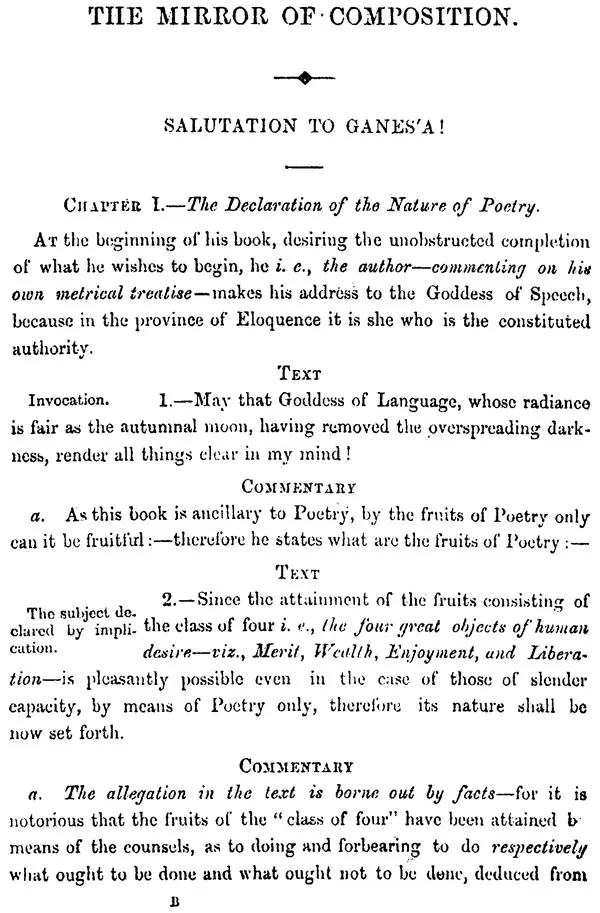

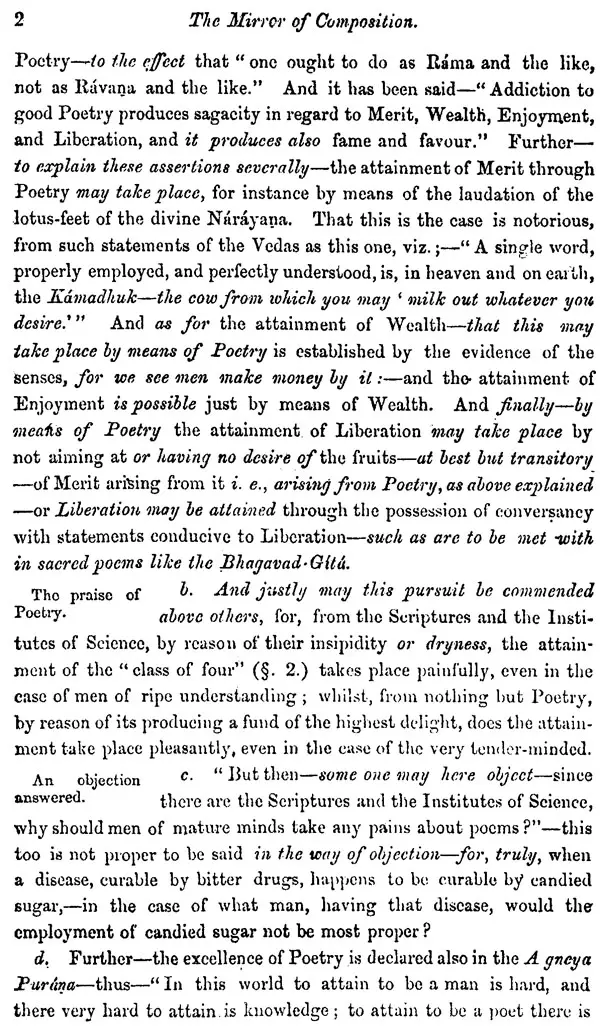

**Contents and Sample Pages**