Music: Its Form, Function and Value (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM435 |

| Author: | Swami Prajnanananda |

| Publisher: | MUNSHIRAM MANOHARLAL PUBLISHERS PVT LTD |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1979 |

| Pages: | 200 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 370 gm |

Book Description

Music: its Form, Function and Value is an outcome of the three lectures, delivered Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. Now those lectures have sufficiently been elaborated and enriched by addition of a new a cheaper and new materials and by Appendices.

Indian music is a systematic and methodical subject. So in under to explore the materials and facts of music, based absolutely on historical records and findings, we should know the process of study of music as well as the scientific and historical method of enquiry into or musical subject, which can be said to be the research-work on music and musicology.

It is needless to mention that method of study of music and method of research-work in music convey the same idea. The field of study of music is vast, and it requires a spirit of love and care. We find today a growing taste and burning thirst for knowledge of acquiring records and genuine history of music as well as real meaning and value of learning the art of music. There are many materials of music are yet unexplored, and there are many Sankrit treatises on music are yet unpublished. But many of the books on music are available now and many of the treasures on music are laid down in those books. It is true that practical lessons on music are more valuable than theoretical knowledge, but yet shastras are essential to unfold the mystery of adhand. So we all the time admit that theory and practice-shastra and sadhana should go side to compete the field of knowledge of music. We know that India was invaded by many foreign nations, and so fusions of culture and art were made possible for intercourse and interchange of many ideas and matters. Indian music was some times influenced by the Arabian and Persian music, and similarly musical arts of Arabia and Persia were influenced by Indian music. In was possible especially in the time of the Emperor Asoka. During his time religious Buddhist missionaries were sent all over the Western countries, and there was an interchange of art, education and culture. There were trade routes between India and other foreign countries, and passages were open both in seas and land. And from those routes of trade and commerce, many of the materials of art, culture and religion also intermixed both in the Eastern and the Western countries. Swami Abhedananda, Mr. Garrett and Dr. S. Rahakrishnan have mentioned about those fusions of art, culture and religion in their books, India and Her People, Legacy of India and Eastern Religion and Western Thought. It is the tendency of the human society to imitate or to imbibe newer thoughts and ideas from the neighbouring peoples. Materials of music were also interchanged in different periods and history of all nations give evidence of it. So the research workers should be well-equipped with historical knowledge. Histories of different periods substantially supply us genuine records of culture and evolution of materials of music as well as their different forms and methods of culture.

Besides, there are many problems in both Indian and Western music. In this book, many of the salient features and controversial subjects of music have been critically discussed with textual references. Chapter 3, i.e. Function of Music and two Appendices have newly been written for his book. The fourth Chapter dealing with Value of Music formed an important part of this book, and this discussion on Value has been made purely from the aesthetic aspect of music which informs us about the central or essential aspect of music. IT has been concluded that without real appreciation of value, i.e., aesthetic and emotional aspects of music, the mysteries of art of music will not be revealed to either the artistes or the listeners. The practice of musical art education fails to serve any purpose for want of proper knowledge of value of music, and this value lies in the proper appreciation and application of aesthetic part of music as has been before. This aesthetic part of music actually supplies the real essence of music. But often we amiss this essential part of music, in consequence of which creation as well as real appreciation of art of music become fruitless. Music is recognised as the best and greatest art. It is best and greatest because of its aesthetic aspect which brings the sincere and intuitive artistes and the attentive listeners in close touch with the Nadu-Brahman, the undivided divine aspect of Sat-Chit-Ananda. The Nadu-Brahman has been beautifully discussed by Patanjali, Bhatrihari and others in their books, mahabhasya, Vakyapadiya, etc. Mandan-mishra, Nagesha- bhatta and other have elaborated the otheeory of Sphota and especially Bhatrihari and Nageshabhatta have proved that Sphota is no other than Shabda-Brahman,i.e., the Supreme Principle in the form of Word, or Speech (Shabda). The Christian Bible has also admitted that Word existed before creation or manifestation of the world. Swami Abhedananda has thrown light on Word or Cross in ancient India and other countries. The Mandukya Upanishad has explained the true significance of Sphota, which exists in the form of Pranava or Omkara. Patanjali has designated this Pranava as the disclose or pointer of the indeterminate Brahman. In Music, this Pranava has been adopted as a symbol of Sphota, or the shabda-Brahman. Gaudapada in this Karikas on the Mandukya Upanishad has elaborated the Omkara with its matras and padas, and he has said that matraless (a-matra) Turiya or Transcendental Brahman is the prime soul and value of all things of the world. Music admits the Shabda-Brahman as its prime principle, but, at last it goes beyond the Shabda-Brahman and rests on the limitless and boundless prime consciousness which is known as Sat-Chit-Ananda. The final Ananda or Supreme Bliss is the fulfilment of Sat and Chit-Existence and Consciousness. The Upanishad says from Ananda or Supreme Bliss evolved this Manifested universe, everything of the universe rest on Ananda, and at last dissolve in Ananda.

This Ananda is a birthless and deathless immortal Existence, which is the ideal of all mortal beings, and music is the surest means to take all to the divine Temple of that immortal all-blissful Existence, and so much is the great art that informs us of that precious value. Therefore music is the best medium or means which should be adopted, nurtured and nourished with care, and should be followed with concentrated attention and effort, so as to reach the goal of life.

In this connection, I owe my sense of gratitude to Dr. Shrimali, the former Vice-Chancellor of the Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi (U.P.) for whose inspiration I delivered the lectures on Muisc: its Form, Function and Value in his University on the 24th, 25th and 26th April, 1974. I also offer my thanks to Dr. (Miss) Premlate Sharma, the Dean and able Guide to the Research students on Music in the Banaras Hindu University. I offer also my thanks to Shri Jyotish Bhattacharyya, the Head of the Department of Fine Arts in the Banaras Hindu University.

In this connection, I offer my loving thanks to Swami Paramatmananda Maharaj of the Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta, for carefully typing and preparing the manuscript of this book. I express my thank to Shri Davashis Hore for preparing the Index for this book. Besides, I offer my sense of gratitude to Principal Dipti Bushan Dutta and Srimati Aruna Dutta for taking deep interest in the publication of this book. Next I offer my thanks to Swami Pranaveshananda Maharaj and Swami Buddhatmananda Maharaj for encouraging me to prepare and publish this book.

I shall consider my attempt fruitful if this book is appreciated by the lovers of music.

The compass of Indian music is large and vast, and it includes all the types and forms of both vocal and instrumental music, dance and drumming (nrtta and vadya). Indian music is considered as a fine art for its finer taste and feeling. Besides, it helps to create emotive feeling and intuitive perception of the artistes and audiences. Indian music is foremost and finest among other fine arts, architecture, sculpture, and painting. Drama, poetry and other arts also create emotion and pleasure, but art of music surpasses them all for its direct charming and soothing qualities. The German philosopher Hegel has beautifully described the characteristic of Western music, and after comparing music with architecture, sculpture, painting, and poetry, he has admitted the superiority of music in his book, Hegel's Aesthetics, II (Oxford, 1975).

Hegel says: "What music claims as its own is the depth of a person's inner life as such, it is the art of the soul and is directly addressed to the soul. Painting too, for example, as we saw, can also express the inner life and movement, the moods and passions, of the heart, the situations. conflicts, and destinies of the soul, but it does so in faces and figures and what confronts us is pictures consists of objective appearances from which the perceiving and inner self remains distinct. No matter how far we plunge or immerse ourselves in the subject-matter, in a situation, a character, the forms of a statue or a picture, no matter how much we may admire such a work of art, may be taken out of ourselves by it, may be satisfied by it -it is all in vain, these works of art are and remain independently persistent objects and our relation to them can never get beyond a vision of them. But in music this distinction disappears. Its content is what is subjective in itself, and its expression likewise does not produce an object persisting in space but shows through its free unstable soaring that it is a communication which, instead of having stability on its own account, is carried by the inner subjective life, and is to exist for that life alone. Hence the note is an expression and something external, but an expression which, precisely because it is something external is made to vanish again forthwith. The ear has scarcely grasped it before it is mute, the impression to be made here is at once made within, the notes re-echo only in the depths of the soul which is gripped and moved in its subjective consciousness.

"This object free inwardness in respect of music's content and mode of expression constitutes its formal aspect. It does have a content too but not in the sense that the visual arts and poetry have one, for what it lacks is giving to itself an objective configuration whether in the forms of actual external phenomena or in the objectivity of spiritual views and ideas."

As for the course we intend to follow in Our further discussions, we have:

(I) to bring out more specifically the general character of music and its effect, in distinction from the other arts, in respect both of its material and of the form which the spiritual content assumes.

(2) Next we must explain the particular differences in which the musical notes and their figurations are developed and mediated, in respect of their temporal duration and the qualitative differences in their real resonance.

(3) Finally, music acquires a relation to the content it express- es in that, either it is associated as an accompaniment with feelings, ideas, and thought already expressed on their own account in words, or launches out freely within its own domain in unfettered independence.

Regarding the character of music in general, he says: "The essential points of importance in relation to music in general may be brought before our consideration in the following order:

(a) We have to compare music with the visual arts on the one hand and with poetry on the other. (b) Next, therefore, we must expound the manner in which music can apprehend a subject-matter and portray it.

(c) In the light 0 f this manner of treatment we can explain more specifically the special effect which music, in distinction from the other arts, produces on our minds."

Hegel says that in respect, music in distinction from the other arts, lies to near the essence of that formal freedom of the inner life to be denied the right of turning more or less away above the content, above what is given.

"In poetry, the sound as such is not elicited from various instruments invented by art and richly modified artistically, but the articulate tone of the human organ of speech is degraded to being a mere token of a word and acquires therefore only the value of being an indication, meaningless in itself, of ideas."

"If we look at the difference between the poetic and the music- al use of sound, 'music does not make sound subservient to speech but takes sound independently as its medium so that sound just as sound, is treated as an end in itself. The realm of sound, as I have indicated already, has a relation to the heart and a harmony with its spiritual emotions, but it gets no further than an always vague sympathy, although in their respect a musical composition, so long as it has sprung from the heart itself and is penetrated by a richness of soul and feeling, may even so be amply impressive."

Regarding effect of music in general, Hegel says: "From this trend of music we can derive the power with which it works especially on the heart as such, for the heart neither proceeds to intellectual considerations nor distracts our conscious attention to separate points of view, but is accustomed to live in deep feeling and its undisclosed depth. For it is precisely this sphere of inner sensibility, abstract self-comprehension, which music takes for its own and therefore brings movement into the seat of inner changes, into the heart and mind as this simple concentrated centre of the whole of human life.

"(a) Sculpture in particular gives to its works of art an entirely self-subsistent existence, a self-enclosed objectivity alike in content and in external appearance. Its content is the individually animated but independently self-reposing substance of the spirit, while its form is a three-dimensional figure. For this reason, by being a perceptible object, a sculpture has the maximum of independence. As we have already seen in considering painting (pp. 805-6), a picture comes into a closer relation with the spectator, partly on account of the inherently more subjective content which it portrays, partly because of the pure appearance of reality which it provides, and it proves therefore that it is not meant to be something independent on its own account, but on the contrary to be something essentially for apprehension by the person who has both vision and feeling. Yet, confronted by a picture, we are still left- with a more independent freedom, since in its case we always have to do with an object present externally which comes to us only through our vision and only thereby affects our feeling and ideas. Consequently the spectator can look at a picture from this angle or that, notice this or that about it, analyse the whole (because it stays in front of him), make all sorts of reflections about it, and in this way preserve complete freedom for his own independent consideration of it.

(b) A piece of music, on the other hand, does also proceed, like any work of art, to a beginning of the distinction between subjective enjoyment and the objective work, because in its notes as they actually sound it acquires a perceptible existence different from inner appreciation, but, for one thing, this contrast is not intensified, as it is in visual art, into a permanent external in space and the perceptibility of an object existing independently, but conversely volatilizes its real or objective existence into an immediate temporal disappearance, for another thing, unlike poetry, music does not separate its external medium from its spiritual content. In poetry the idea is more independent of the sound of the language, and it is further separated from this external expression than is the case in the other arts, and it is developed in a special course of images mentally and imaginatively formed as such. It is true that it might be objected that music, as I have said previously, may conversely free its notes from its content and so give them independence, but this liberation is not really compatible with art."

In fact, Hegel has discussed about Western music, but his views and broad principles are undoubtedly applicable to both Western music and Indian music. While discussing about Indian music and its nature. Rai Bahadur Bisan Swarup has rightly said that a music artist has a more difficult task to perform than the other artists, sculptors, painters, poets and architects, because, while the latter present their work to the people in a tangible shape with feelings expressed, the musician has to do more than that as he stimulates the imagination of his audience and thereby engenders in them those feelings, to make himself and his art to be understood.

The scientific treatment of music, as a subject distinct from poetry, enables the artists to compose suitable combinations, a variety of tone, and tunes, some to express particular feelings and stimulate particular emotions, i.e., emotional sentiments, some for devotional purposes, some for soothing the heart andbrain and pleasing the ear, and so on. A good and accomplished musician can sing any song in any of the tunes or melodies, and can select his tunes or melodies, for his songs to suit the particular occasion or the time of the day. This is a great advantage for him to make his music effective and loving."

We have discussed before that music surpasses other fine arts in its quality and appeal, and it is a fact that the art of music has to exert much more for being effective than other arts. Poetry is possessed of words and suitable phrases by which the poet can express his poetry with adequate emotive feeling, but, in the case of music, it means evolving of principles by carefully considering the effect of each note as well as combination of notes. Many of the emotive feelings are practically expressible by variations in tone of the voice, but those are difficult to catch the mind, or to express feeling in the mind at large.

Music is a suitable medium for creating and appreciating beauty. "Beauty was the vital principle," says Kr kasu Okakura, "that pervaded the universe-sparkling in the light of the stars, in the glow of the flowers, in the motion of a passing cloud, or the movements of the flowing water. The great World-Soul permeated men and nature alike, and by contemplation of the world life expanded before us, in the wonderful phenomena of existence, might be found the mirror in which the artistic mind could reflect itself." Music is recognised as the pure mirror, on which the reflection of the World-soul can be seen, and from the reflection we can gradually catch the flow of the real all-pervading soul with the help of concentration and meditation, and we believe that the Indian artists can witness the self-effulgent light of music, saturated with the all-blissful and all-loving presence of the Beautiful. Music of India is living and loving, and if it is sincerely nourished and cultured, the artistes and the lovers of music can easily realize its surpassing grandeur and sublimity.

| Preface | vii | |

| Introduction | xi | |

| Chapter 1 | A Study of Music | 1 |

| Definition | ||

| Primitive Music | ||

| Mythological Interpretation | ||

| Origin of Music | ||

| Sound is the Norm of Music | ||

| Science of Music | ||

| Indian Con-ception of the Sound | ||

| Sound-Music and Colour-Music | ||

| Philosophy of Colour | ||

| Evolution of Tone has created a History | ||

| Rhythm and Melody in Music | ||

| Fusion of Culture | ||

| Influence on Music | ||

| The Number-Souls of the Pythagorean | ||

| Music in the Vedic Time | ||

| Music in Classical Period | ||

| Schools of Music | ||

| Raga-Ragioi Scheme | ||

| Music in the Epics | ||

| Music is Dynamic | ||

| Problem of Music. | ||

| Chapter 2 | Form of Music | 54 |

| What is Form of Music | ||

| Thoughts transformed into Forms | ||

| Psychological Necessity of Form | ||

| Psychological Aspects of Form -Different Musical Forms | ||

| Musical Ballads in Ancient Times | ||

| Types of Plain-songs | ||

| Development of Early Music | ||

| Vedic Musical Form | ||

| Forms of Jati and Grama Ragas | ||

| Different Forms in the Time of Bharata | ||

| Form of Prabandha | ||

| Changing Phases of Forms of Ragas. | ||

| Chapter 3 | Function of Music | 75 |

| Dual Phase of Function | ||

| Music, Real and Ideal | ||

| Division of Function of Music | ||

| Function of Music and History | ||

| Function of Music in Primitive Time | ||

| In Prehistoric Time | ||

| In Classical Time | ||

| Occasional Phases of Music | ||

| Various Evolutions of Music | ||

| Marga and Deshi Types of Music-Music, Abstract and Concrete | ||

| Alapa and Its Development | ||

| Gana, Giti and SaIigita | ||

| Tone, Tune and Melody | ||

| Revival of Music | ||

| Evolution of Styles and Its Significance | ||

| Responsibilities of the Artistes and the Musicologists | ||

| Music, Static and Dynamic | ||

| Art and Beauty. | ||

| Chapter 4 | Value of Music | 105 |

| Music and other Arts | ||

| Romain Rolland and Music | ||

| Language and Tune in Music | ||

| True Form of Art | ||

| Imagination in Art | ||

| Appreciation of Art | ||

| Work of Art and Aesthetics | ||

| Artistic Value and Aesthetic Value | ||

| Art and Value | ||

| Value, Subjective and Objective | ||

| Intuitive Perception of Vaue | ||

| Emotive Value and the Beautiful | ||

| Art and Beauty | ||

| Indian View of Value | ||

| Indian View of Beauty | ||

| Rasa-theory in Bharata's Natyasatra and Bhoja's Srngara-Prakasa | ||

| Definition of Beauty | ||

| Kant and Beauty | ||

| Croce on Art and Beauty | ||

| Aesthetic Feeling in Music | ||

| Expression and Evocation of Emotion | ||

| Conclusion. | ||

| Appendix I | Heaven and Earth in Music | 147 |

| Appendix II | Value, Aesthetic and Psychology of Music | 157 |

| Bibliography | 171 | |

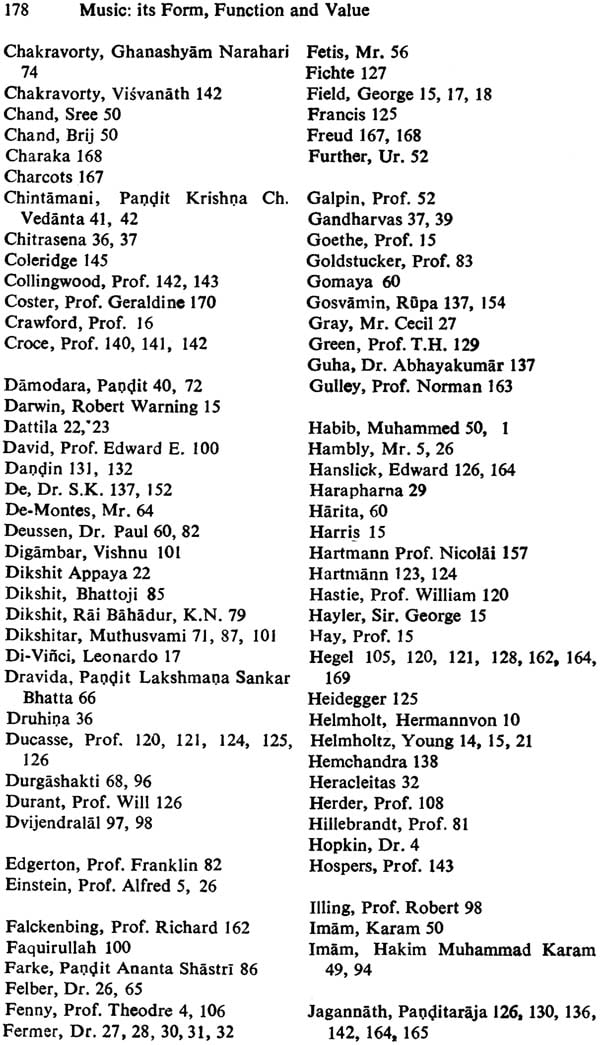

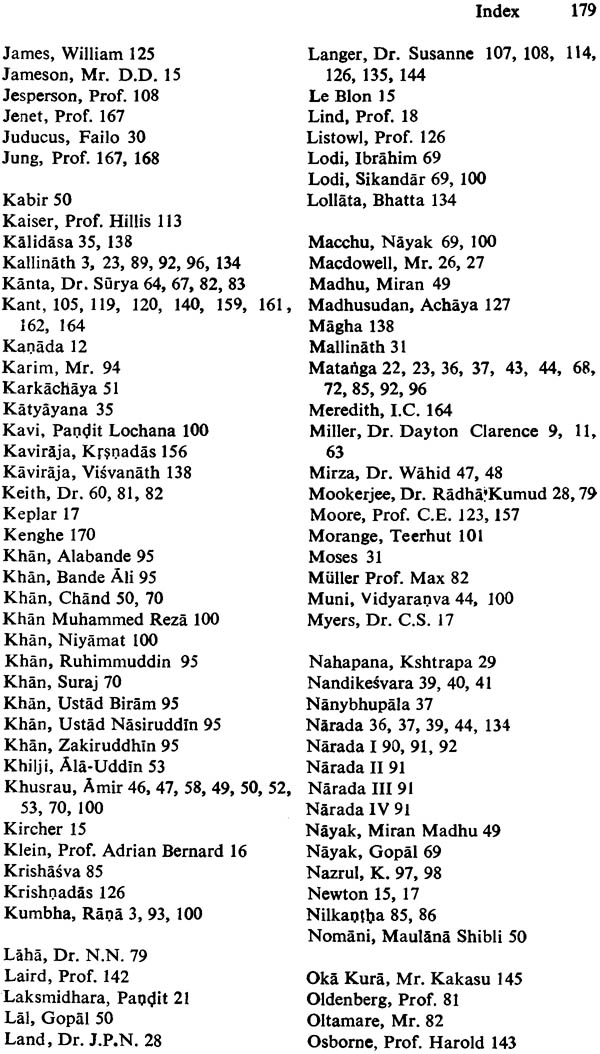

| Index | 77 |