Natyasastra: Sanskrit Text With Transliteration and English Translation (Set of 2 Volumes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAL649 |

| Author: | Manomohan Ghosh |

| Publisher: | Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan |

| Edition: | 2016 |

| ISBN: | 9789385005831 |

| Pages: | 1352 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.5 inch x 6.5 inch |

| Weight | 2.80 kg |

Book Description

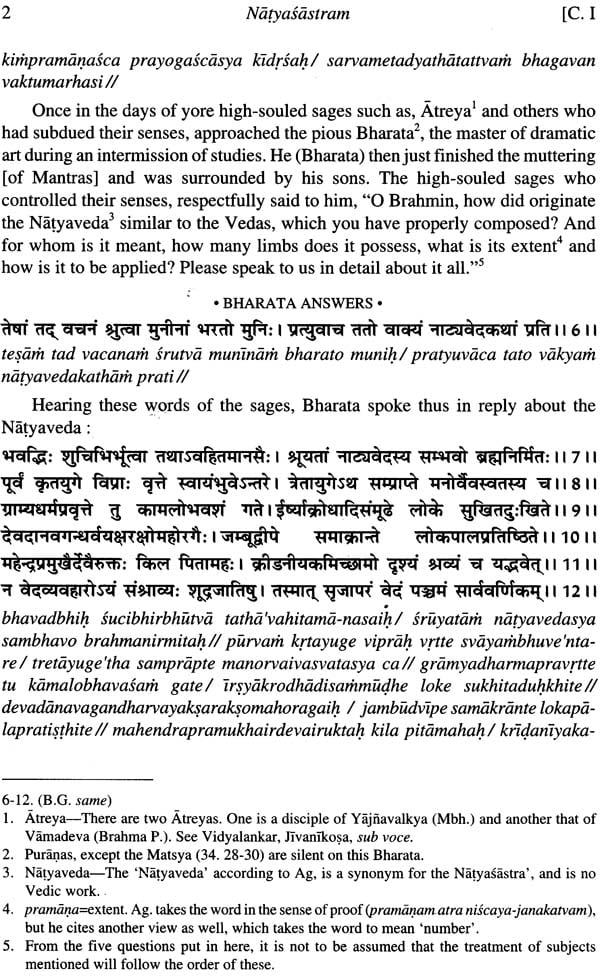

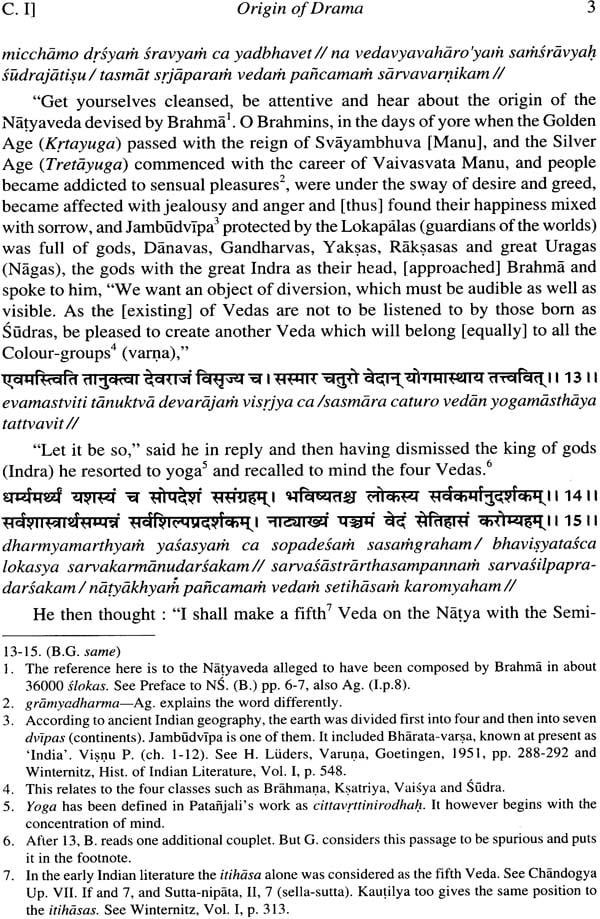

The Harappan dancing girl sculpture shows, how old is the tradition of Natya viz. dance, drama and music in India. Samaveda is dedicated primarily to music; this again shows the importance of performing arts in ancient India. With such a rich legacy of dance, drama and music, India has given various great scriptures of this tradition to the world. The Natya sastra is such a scripture only. This scripture had been accepted as fifth Veda, as the same is gist of Vedas. According to scripture itself, "The recitative (pathya) he took from the Rgveda, the song from the Samaveda, the Histrionic Representation (abhinaya) from the Yajurveda and Sentiments (rasa) from the Atharvaveda and thus was created the Natyaveda.

With thirty-six chapters and over six thousand verses, this is encyclopaedia of Natya Vidya (Vidya of dance, drama and music). This comprises of every single aspect of Natya viz. it talks about the issues related literary constructions, set up of stage, details related to musical scales and murcchas, analysis of dance forms which considers several body gestures or mudras and movements along with their impact on viewers, it also educates the viewers about the etiquettes to be followed while watching a performance and it deals with Rasas.

Bharata muni describes 15 types of drama ranging from one to ten acts. Individual chapters deal with aspects such as makeup, costume, acting and directing etc.

With detailed theory of drama, Natyasastra is comparable to the Poetics of Aristotle. Bharata Muni refers to bhavas, the imitations of emotions, as per him eight principal rasas are srngara rasa (love), karunya rasa (pity), Raudra rasa (fury), Vibhatsa rasa (disgust), Vira rasa (heroism), Adbhuta rasa (wonder), Bhyanaka rasa (horrific) and Hasyarasa (comedy) however Mahamahesvara Abhinava gupta who wrote a commentary on it also, later setup ninth rasa the santa rasa and said all the other rasas are part of it.

The Natyasastra is the first major text that deals with music at length. It is considered the defining treatise of Indian classical music until the 13th century, when the stream bifurcated into Hindustani classical music in North India and Carnatic classical music in South India; the stronghold of the Hindu kingdoms. Even till date its strict follow up can be seen in performing arts of south India.

With major focus on musical instruments in its musical art narration the Natyasastra also talks about several aspects of musical performance, particularly its application to vocal, instrumental and orchestral compositions. Natyasastra also talks about jatis which are the origin of the notion of modern melodic structures called ragas.

The present edition is critical edition with Samskrta text, transliteration, annotated English translation along with detailed index, which makes it very useful for research scholars, performing arts experts and enthusiasts.

The Natyasastram of Bharata-muni is a unique work of Indian culture and literature. It is an encyclopaedic work which has now been made into two volumes (previously in four volumes) and contains thirty-six chapters. This voluminous work deals with all possible subjects connected with the stage-craft including the construction of plays of different kind. The learned editor and translator of the work concludes here in this work that it was written in the fifth century B.C., and, it shows that the Indians reached a high level of perfection in presenting as well as constructing dramatic works. In spite of their occasional pre-occupation with man's destiny in the other world, they paid serious attention to the earthly aspects of their life. The Natyasastra is valuable in several respects as it presents a glimpse of the activities of the ancient Indian writers in the field of dramaturgy and histrionics which had begun before Panini composed his grammar some time about 600 B.C.

The original text of the Natyasastra was written more than two millenniums ago but it was discovered about a hundred and fifty years ago when the French Sanskritist Paul Regnaud published in 1880 chapter XVII, and in 1884, chapter XV (in part) and the chapter XVI of the Natyasastra with translation. This was followed by his publication of chapters VI and VII in 1884. And J. Grosset, another French scholar and a pupil of Regnaud, published later (in 1888) its chapter XXVIII (with translation) which treated of the general theory of Indian music. However Pt. Shivadatt and Kashinath Pandurang Parab published the original Sankrit text in 1894 from Bombay, and it was followed by J. Grosset's critical edition of its chapters I-XIV based on all the MSS. available up till that date.

The present translator encountered many difficulties and gathered materials from the works of his predecessors, and it cannot be claimed that the work has reached us in its original form. There are in it a number of interpolations of later date which the translator has discussed in detail. According to Sarndeva the commentators who set themselves to the task of explaining or elucidating the Natyasastra are Lallata, Udbhata, Sankuka, Abhinavagupta and Kirtidhara, As J. Grosset's text does not go beyond the chapter XIV, the translator had to prepare a critical edition of the remaining chapters bofore taking up the translation. For this he depended principally upon Ramakrishna Kavi's edition (Baroda, 1926-1954) including Abhinavagupta's ommentary, as well as the Nirnayasagar and the Chowkhamba editions (the first Bombay 1894 and the second, Benares, 1929).

The translator had to make selection of the text from two distinct recensions available and, he thought it prudent to adopt readings from both the recensions. Since, the text of the Natyasastra has a complicated text-history of its own, the translator had to first reconstruct the text ably and then he did interpretation of it. The translation has been made literal as for as possible except that the stock words and phrases have been mostly ignored.

As for drama, it naturally continued to be looked upon by Indians as spectacles (preksa) or things to be visualized, even after great playwright creators like Bhasa, Kalidasa, Siidraka, Bhavabhuti and Visakhadatta had written their dramas which in spite of their traditional form were literary masterpieces. It need not say that the present work contains all the relevant materials required for a perfect dramatic treatise.

Now the publishers are going to bring out the new edition of this valuable work in two volumes in order to make it handy for the readers. As the work was in four separate volumes, each two volumes for the translation and the text separetely, the present scheme of publication in taking the text and translation together will facilitate the reader definitely when they will find the text with the translation itself. The learned translator has already disclosed the reasons and the circumstances through which he had to pass when he was working with translation, and thereafter the editing of the text matter. All this has been very clearly presented in hi writing of the Introduction of the text-history. It is but natural that the translator was bound to publish each volume separately, and, he deserves the gratefulness on the part of the readers for having been made such an important work available to them even after big gaps of time. The translator has regretted the inconveniences to readers in his preface to earlier edition.

The present edition has undergone certain changes in course of making it into two volumes. First of all, the Introduction given in each volume of the translation and the text has been put at one place in the beginning of the first volume it elf with minor editing in it. But it has been decided to incorporate the Introduction to text after the Introduction to translation separately. Similarly the preface given to each volume in the earlier edition has been put together in order after minor editing. The other things have also been retained without any omission whatsoever. It is hoped that readers will welcome the present scheme of bringing the text and the trnaslation together in two volumes and will find his edition of the Natyasastra more useful.

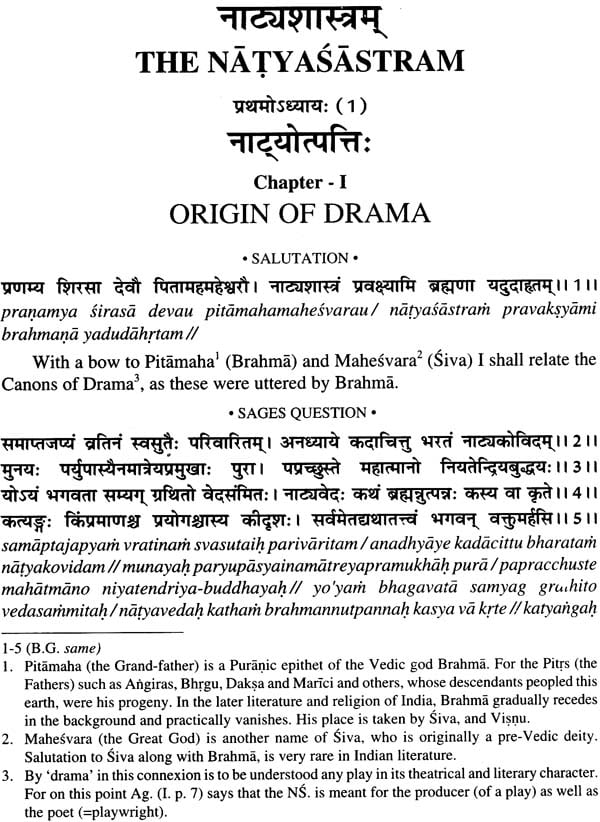

1. Scope and Importance of the Natyasastra

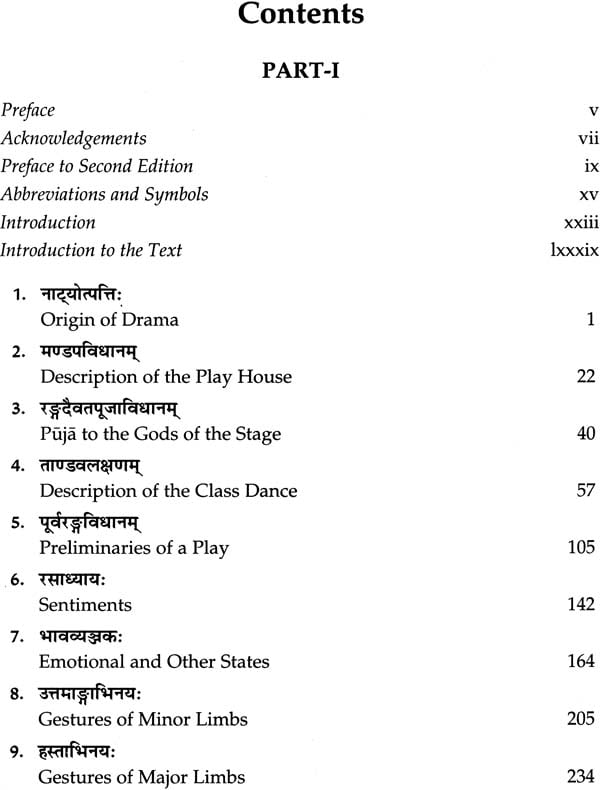

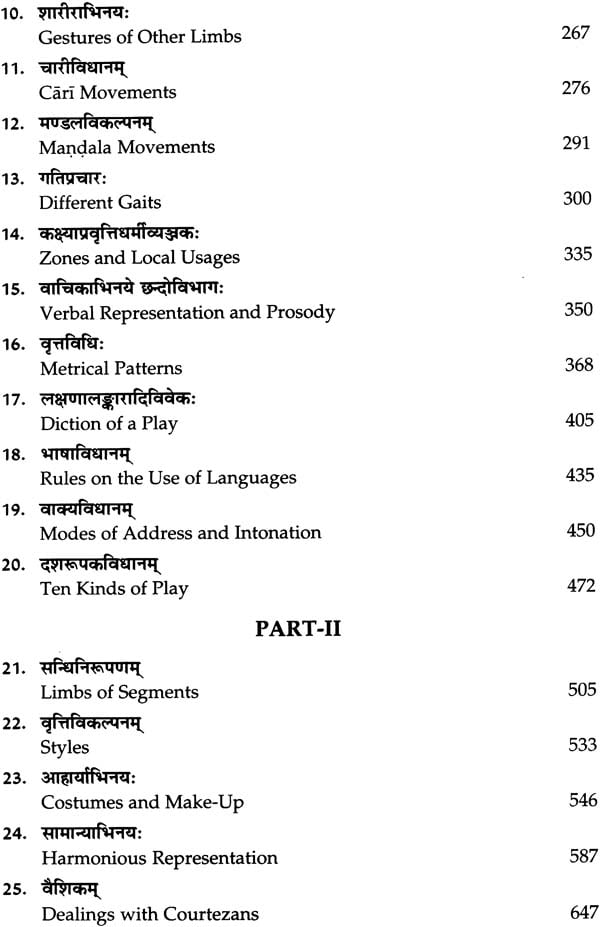

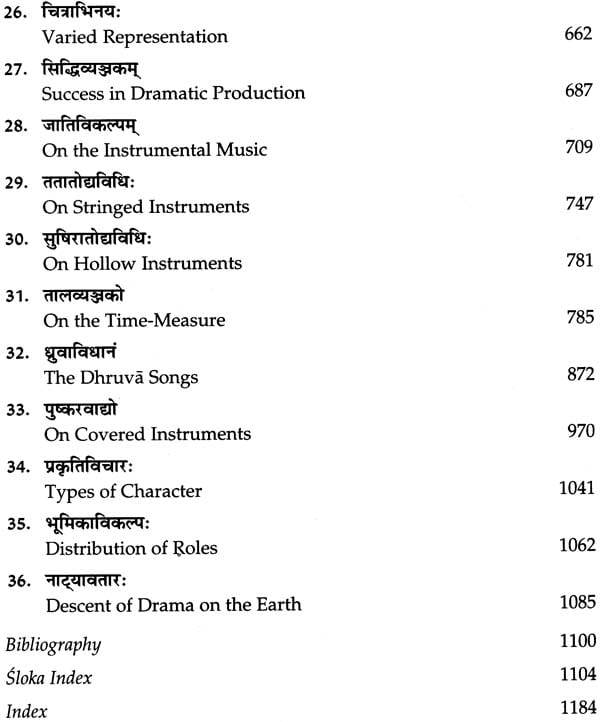

1. The Natyasastra written more than two milleniums ago is a unique work of Indian literature. Though the title relates to theatre, it is in fact an encyclopedia dealing with all possible subjects connected with the stage. This voluminous work composed almost entirely in verse (about 6,000 couplets) with a sprinkling of prose and divided into thirtysix chapters, contains besides other valuable data on the history of ancient Indian culture, discussions on the following topics:

i. Mythical origin of theatre, its coming down on the earth.

ii. Construction of a playhouse, a stage, a tiring-room and auditorium etc. ceremonies relating to the construction.

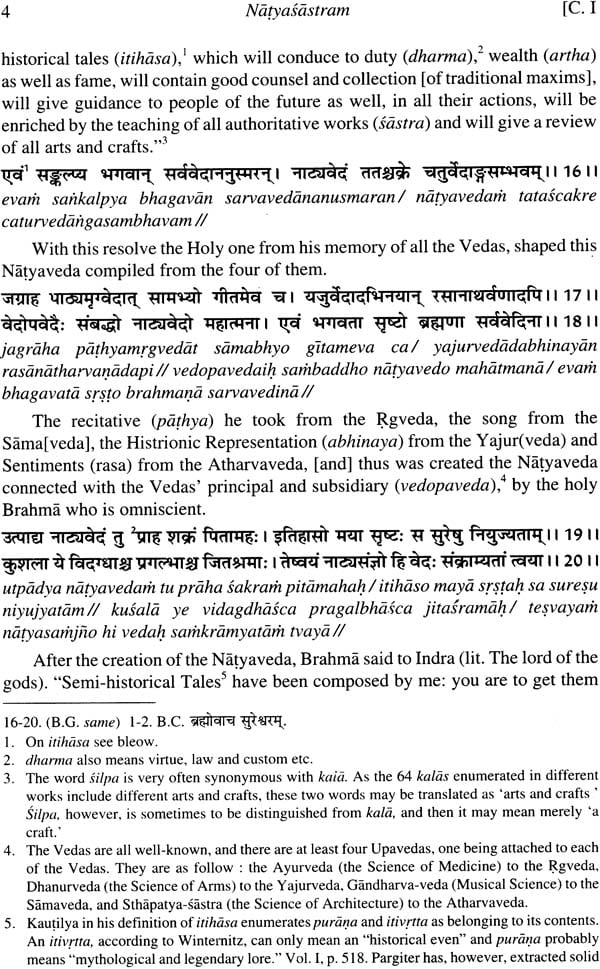

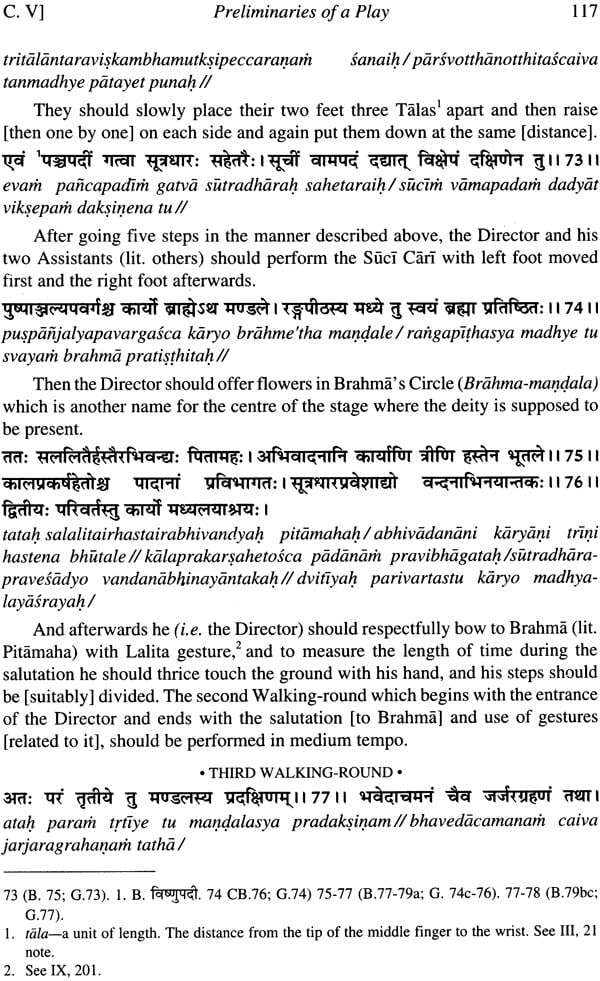

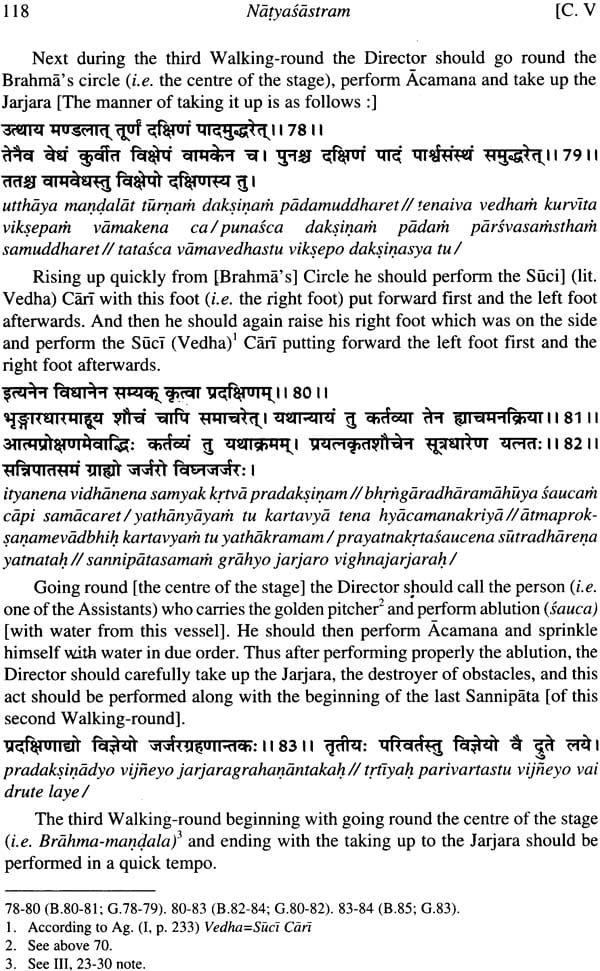

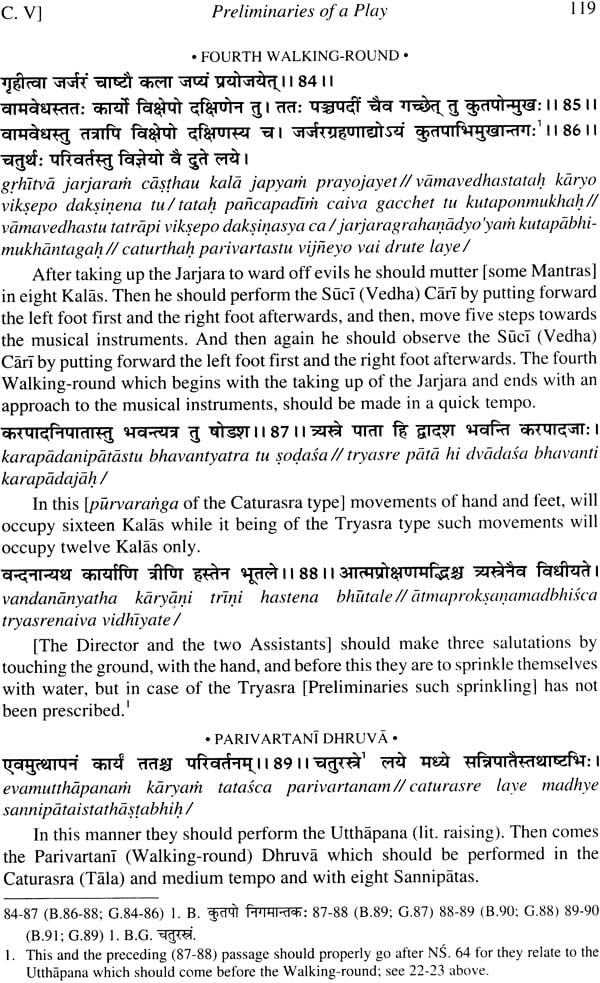

iii. Preliminaries to a dramatic performance: ceremonies including songs, chants, dances and instrumental music.

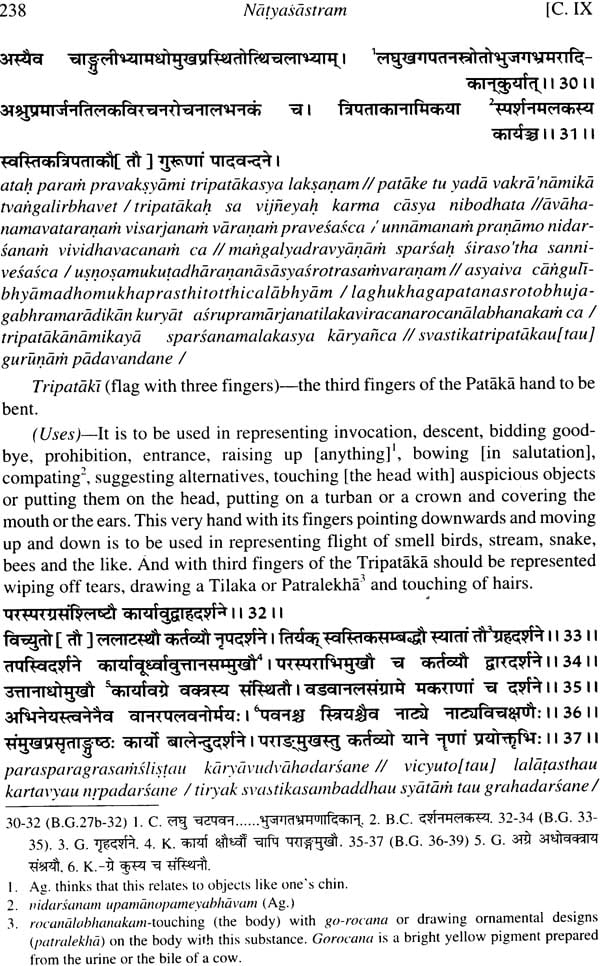

iv. Choreographic elements: dance, gestures and movements of different parts of the body (head, neck, eyes, hands, legs etc.) and body in some conventional postures.

v. Costumes and make-up.

vi. Classification of plays, analysis of their structure.

vii. Poetic aspects of plays, and metres and figures of speech used in them.

viii. Theory of music, metres of songs, chants, elocution, modes of playing instruments (Vinas, flutes and drums and Talas (time-measure) to be observed during songs, and playing of instruments.

ix. Roles and characters in plays: their classification, description, and training of actors and actresses, members of theatrical troupes, and qualification of an ideal stage-manager.

x. Criticism of a dramatic performance.

2. Some of the topics, especially an analysis of typical plays and their poetic aspects (nos.vi and vii) may appear to be superfluous in connection with the production of plays. But this is not actually so. For during the early period of Indian drama, independent playwrights as a class were non-existent, and every troupe had its own play-wright who accompanied it from place to place, and utilized local history and legends to compose plays for entertaining a large number of people as well as for adding to its repertoire. It was with a view to help such playwrights that the author of the NS. discussed in detail the structural design of the various types of play and its elaboration. It is not known if Abhinavagupta looked into this matter in such a light; still his reply to the anticipated criticism was that it (the Natyasastra) is for the guidance of playwrights as well as of producers. As drama in any form is primarily and essentially a spectacle, an acquaintance with the rules of its production should be considered indispensable for playwrights. For it is a well known fact that good many literary dramas are not taken up for performance, because they are not suitable for being put up on the boards. The author of the Natyasastra was evidently conscious about this close connection between the literary and technical aspects of theatrical production, and treated both of these with almost equal care. Hence his work naturally assumed the form of an encyclopedia. It is therefore no wonder that this was often quoted and referred to by authors who wrote afterwards on gestures, poetics, prosody, music and even Prakrit grammar. With equal justification it was also utilized by commentators of different Sanskrit and Prakrit plays. All the later writers on dramaturgy depended greatly if not exclusively, on this valuable work, and acknowledged their debt to the mythical Bharata.

3. Topics of the Natyasastra discussed above are, however, principal ones, and many minor ones come up from time to time.

This shows to what extent the ancient Indian writers were ready to go into details to clarify the subject in hand. But in spite of our great respect for the author, it would be idle to pretend that he followed a plan that can quite satisfy the modem readers. This, however, may not prove to be a handicap in following his main lines of treatment. The real difficulty about understanding and interpreting his great work comes from its peculiar textual tradition, which developed obscurities through being copied and recopied for persons who were later cut off from the original tradition. And it is probably on this assumption that one can explain the fact that from about the seventh century, a number of, talented scholars began to study the work closely and write commentaries on It Abhinavagupta (about 10th-11th century) was perhaps the last great name amongst them. His work alone has luckily come down to us, though not in accurate and complete manuscripts. Publication of this commentary as well as the very useful work done by a number of modern scholars has considerably reduced the initial difficulty of studying with profit the contents of the NS. A brief history of all this will be necessary for realizing the nature and magnitude of the task undertaken.

2. A Short History of the Study

4. Since the West came to know of the Sanskrit drama through William Jones's translation of the Sakuntala (the popular name of the Abhijnana-Sakuntalam) the nature and origin of the ancient Indian theatre, have always interested scholars, especially the Sanskritists, all over the world. H.H. Wilson who published in 1826 the first volume of his famous work on the subject deplored that the Natyasastra, mentioned and quoted in several old commentaries and other works, had been lost for ever. F. Hall who published in 1865 his edition of the Dasarupa. a late work on dramaturgy, did not see any MS. of the Natyasastra till the printing of his work had greatly advanced. And for the time being he published the relevant chapters of the work as an appendix to his Dasarupa, Afterwards he undertook to critically edit the MS. of the Natyasastra he had acquired; but this venture was subsequently given up. In 1874 W. Heymann, a German scholar, published on the basis of South Indian MSS, discovered up till that date a valuable article on the contents of the Natyasastra. The French Sanskritist Paul Regnaud published in 1880 chapter XVII and in 1884 chapter XV (in part) and the chapter XVI of the Natyasastra with translation. This was soon followed by his publication of chapters VI and VII in 1884 And J, Grosset, another French scholar and a pupil of Regnaud, published later (in 1888) its chapter XXVIII, (with a translation) which treated of the general theory of Indian music.

5. But the different chapters of the work and studies on them, which were published up till 1888, though very helpful for the understanding of some aspects of the ancient Indian dramatic works, cannot be said to have thrown any considerable light on the exact nature of the ancient Indian plays, especially the manner of their production on the stage. Sylvain Levi's Le Theatre indien (1890) in which he discussed comprehensively the contribution of his predecessors in the field and added to it greatly by his own researches, made unfortunately no great progress in this specific direction. Though he had access to three more or less complete MSS. of the NS Levi does not seem to have made any serious attempt to make a close study of the entire work except its chapters XVII-XX (XVIll-XXII of our text) and XXXIV. The reason for his relative indifference to the contents of the major portion (nearly nine-tenths of the work seems to be principally the corrupt nature of his MS. materials. Like his predecessors, Levi paid greater attention to the study of the literary form of ancient Indian plays with the difference that he utilized for the first time the relevant chapters of the NS. to check the accuracy of statements of later writers on the subject like Dhananjaya and Visvanatha who professed their dependence on it. But whatever may be the drawback of Levi's magnificent work; it did an excellent service to the history of ancient Indian drama by focussing the attention of scholars on the great importance of the NS. Almost simultaneously two Sanskritists in India as well as one in the West were planning its publication. In 1894 pandits Shivadatta and Kashinath Pandurang Parab published from Bombay the original Sanskrit text of the work. This was followed in 1898 by J. Grosset's critical edition of its chapters I-XIV based on all the MSS. available up till that date.

6. Though nearly seventy years passed after the publication of Grosset's incomplete edition of the NS, it still remains one of the best specimens of modern Western scholarship, and though to the light of the new materials available, it is possible nowadays to improve upon his reconstruction in a few places, Grosset's work will surely retain for a long time a landmark in the history of the study of this important text. It is a pity that this very excellent work remains unfinished. But a fact equally deplorable is that it failed to attract sufficient attention of scholars interested in the subject. Incomplete though it was, it nevertheless contained a good portion of the rules regarding the presentation of plays on the stage, and included valuable data on the origin and nature of ancient Indian drama; but no one seems to have subjected it to the searching study it deserved. Whoever wrote on ancient Indian plays after Levi depended more on his work than on the NS. It self, even when this was available (at least in a substantial part in a critical edition. It may very legitimately be assumed that the reasons which conspired to render the NS. rather unattractive included among other things, the difficulty of this text which was not yet illuminated by a commentary.

7. Discovery in the first quarter of the present century of the major portion of such a commentary written by the Kashmirian Abhinavagupta seemed to give, however, a new impetus to the study of the work. And it appeared for the time being that the NS. would yield more secrets treasured in the body of its difficult text. But the publication in 1926 of the first volume of the Baroda edition of the work including Abhinava's commentary, disillusioned the expectant scholars. Apart from the question of merit of this commentary and its relation to the available versions of the NS., it suffered from a very faulty transmission of the text. Not only did it contain numerous lacunae, but; quite a number of its passages were not liable to any definite interpretation due to their vitiated nature. Of this latter condition the learned editor of the commentary says, "the originals are so incorrect that a scholar friend of mine is probably justified in saying that even if Abhinavagupta descended from the Heaven and saw the MSS. he would not easily restore his original reading. It is in fact an impenetrable jungle through which a rough path now has been traced". The textual condition of Abhinava's commentary on the remaining chapters published later is also not appreciably better.

8. But whatever may be the real value of the commentary, the first three volumes of the NS. published from Baroda, which were avowedly to give the text supposed to have been taken by Abhinavagupta as the basis of his work, presented also considerable new and valuable materials in the shape of variant readings collated from numerous MSS. of the text as well as from the commentary. These sometimes throw a new light on the contents of the work. A study of these together with a new and more or less complete text of the NS. published from Benares in 1929, was justifiably considered a desideratum. The present work has been the result of such a study, and in it has been given for the first time a complete translation of the NS. based on a text critically reconstructed by the author.