Ornamentation in Indian Architecture - Oriental Motifs and Designs

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAP371 |

| Author: | S.P. Verma |

| Publisher: | Aryan Books International |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| ISBN: | 9788173055188 |

| Pages: | 270 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 13.0 inch x 9.5 inch |

| Weight | 1.20 kg |

Book Description

For a building to become architecture, it must be thematically essentialized through a process of ornamentation. The product of this process is beautify, or embellish, or that naturally does this. Leon Battista Alberti (AD 1404-1472), an architect considered ornament as something additional or applied: "... ornament may be defined as a form of auxiliary light and complement to beauty. From this it follows, I believe, that beauty is some inherent property, to be suffessed all through the body of that which may be called beautiful; whereas ornament, rather than being inherent, has the character of something attached or additional.

Ornamentation is that component of the art product which is added, or worked into it, for purpose of embellishment. In general, however, "ornamentation" refers to motifs and themes used in art objects, buildings, or any surface without being essential to structure and serviceability. In this sense, "ornamentation" and "decoration" are used, for the most part, interchangeably, although "decoration" has, in addition, its own special applications in the field of interior decoration and theatrical decoration, or "decor". Ornamentation, in architecture, applied embellishment in various styles that is a distinguishing characteristic of buildings. It often occurs on entablatures, columns, and the tops of buildings and around entryways and windows. Upto the middle of the 3rd century BC the course of building art in India is only indistinctly visible. With Asoka, the third Mauryan ruler of Magadha, who ascended the throne in 274 BC, the manifestation of Buddhist art contributed to the art and architecture of the time. It included number of stupas, monolithic pillars, group of rock-cut chambers and shrines. These productions directly effected the course of the art of building. Finding expression from wood in another and more lasting material such as dressed stone proved a decisive step in the cultural evolution of people. Asoka inaugurated Buddhism as the state religion of the country and with this change India marked advance in the arts. The shapes and decorative forms employed by the Indian artificers were obviously derived from the art repertory of other people, and only a few of them were indigenous. Such exotic forms are clearly Greek, Persian and a few perhaps Egyptian extraction. Brown has to say that this development of the art of working in stone, therefore, which Asoka introduced into the country represents an Indian offshoot of that forceful Greeco-Persian culture which flourished with vigour in Western Asia.

A classical art school composed of Pharoic — Hellenic — Iranian elements of distinctly effective character has a direct bearing on the style which appeared in Buddhist India. The well-known conventional motifs as the honeysuckle and palmette, the bead and fillet, the festoons and the cable moulding of Hellenic extraction actuated the Indian decorative elements. The building art followed the same course under the Sungas and Andhras (185 BC-AD 150 ). It added the gateways (toranas), displaying far more impressive design and excel in any style of architecture of ornamental purpose and imagery. The Sanchi toranas are the result of entirely Indian tradition and genius (Fig. 1). During this period, as to the stone carving, both in design and technique, there appear appreciable progress, as the plastic treatment of the Bharhut railing and the Sanchi toranas bear testimony of it (Fig. 2). Additionally, imaginative symbols of Vedic times were employed in Buddhist art, e.g., the wheel, the tree, the lotus, the trisula, the mounted gryphon, and many other motifs reproduced in a variety of forms in the subsequent art of India (Fig. 3). The Buddhist architectural surface ornaments of great elegance and appropriateness, and, when combined with the architecture, make up a whole its ethnographic as well as for its architectural beauty.

Decoration at Dhamek Stupa at Sarnath (c. AD 600) makes this ruined monument of special interest due to the unusual scheme for the decorative treatment of the stone facing, which includes ornamental elements some having significant implications. Over some of the surface surrounding a diaper pattern carved in floral scrolls appear to have been projected. Here the most original and striking designs are those forming a wide border carried around its lower circuit, one of which is floral and the other geometrical, each expressive of its own historical tradition (Fig. 4). The floral one a spiral motif, typically in Gupta style is a combination of flowing wave-like curves simulating flower stems supporting at intervals a many petalled flower medallion, an artistic conception of notable beauty and grace. Notably it stands forth as the arch type of that distinctive border of spiral curves and foliated medallions which adorns the "screen arches" forming the facade of Qutb mosque at Delhi erected many centuries later Chalukyan architecture (c. AD 450-650) exhibits excellent quality of sculpture and decoration akin to the Gupta temple style. A detailed analysis of temple architecture of both the Jains and the Hindus will show that much of its architectonic character was obtained by the surface being treated and built up of repetitions of the same architectural motif, converted into an element of decoration. The Indian builder knew architecture as a fine or liberal art, but not as a mechanical art. The temple of Kailasa at Ellora, the most stupendous single work of art and an unrivalled example of rock—architecture is finally adorned with sculpture. This plastic decoration is crowning glory something more than a record of artistic form.

The mandapas and rathas of the Pallavas (c. AD 600-900) have to offer nothing afresh in course of decoration. The mandapas at Mamallapuram are of the simplest kind as regards to the architectural treatment but are remarkable for the disposal of sculpture combined with the architectural forms. The rathas, widely known as the "Seven Pagodas” exhibit much the same architectural style as the mandapas. But the quality of the figure sculpture is remarkable.

Cholas (AD 900-1150) renewed the brilliance of architecture, as their architectural undertakings at Badami and Pattadakal manifest. The Chola sculptures exhibited voluptuous treatment of the human figure and there emerged a different animalized motif. It took the form of a string-course, the use of which as a decorative element in the temple scheme was in vogue throughout in the South India temple art. The magnificent temples of Tanjore exhibited remarkably ingenious motifs and devices showing great fertility of invention, as for example a conventional foliage, or "tree of knowledge". These testify supremely imaginative quality of embellishment. The gopurams under the Pandayas (c. AD 1100-1350), the earliest of their kind are however of the simpler and more conventional variety, and their decoration is mainly of the architectural type. The Vijyanagar dynasty (AD 1350-1565) had wonderfully rich and beautiful architecture with sumptuous plastic embellishment.

At this stage of development, the Indian architecture remarkable for the profuseness of its applied decoration reached "the extreme limit of florid magnificence".2 The principal temples of the Vijyanagar, the Vitthala and the Hazara Rama have every stone being chiselled over with the most elaborate patterns, some finely engravedand others modeled in high relief. These often depict animal motifs, half natural half mythical but wholly rhythmic. The hazara Rama temle, small but highly ornamented temple, excels in mural relief decoration. The temple in the fort at Vellore marked the zenith of Vjayanagar style. It excelled in the luxuriant character of its carving considered the richest and most beautiful structure of its kind.

Contents

| Contributors | ix |

| Introduction by S.P. Verma | xi |

| HISTORIC ILLUSTRATIONS (I - CXXXIII) | |

| I and II Decorative Ornaments from an Ancient Jaina Stupa at Mathura | 2 |

| III. Sculptures from an Ancient Jaina Temple at Mathura | 6 |

| IV. Perforated Stone Screen-work from Chalukyan Temples | 8 |

| V. Chalukyan Ceiling from the Temple of Kattesvara, Bellary District | 10 |

| VI. Doorway, East Entrance, Temple of Chaturbhuj, Orchha, Bundelkhund | 12 |

| VII. TO X. Ornaments from the Temples of Virabhadra, Anantapur District, Madras Presidency | 14 |

| XI. Panel and Ornaments on Piers, Ramasvami Temple, Kumbakonam, Tanjore District | 20 |

| XII. and XIII. Carved Panels on the Shrine Pilasters, Nagesvara Temple,Kumbakonam (LXVII), and on the Panchanadesvara Temple (LXVIII), Tiruvadi, Tanjore District | 22 |

| XIV. Pier in the Subrahmanya Shrine, Brahadesvara Temple, Tanjore | 26 |

| XV Teakwood Piers from the Temples of Mailaralingappa, Bellary District, and Margasahayar Temple at Virinjipuram, North Aroot District | 28 |

| XVI. Pier in the Thousand Pillared Mandapa, Minakshi Amman Temple, Madura | 30 |

| XVII. Stone Idol-Couch from a Temple at Banavasi, N. Kanara | 32 |

| XVIII. Ceiling Panel from a Hindu Temple at Vadnagar in Northern Gujarat | 34 |

| XIX. A Ceiling Panel from Anhilwada Patan, North Gujarat | 36 |

| XX. Central Area in the Roof of the Mandapa, or Hall of the Temple at Ittagi | 38 |

| XXI. Tympanum over the Recesses on Each Side of the Principal Mihrab in the Atala Masjid at Jaunpur | 40 |

| XXII. Panel from One of the Smaller Propylons of the Atala Masjid at Jaunpur | 42 |

| XXIII. Bay of a Ceiling from Hilal Khan Qazi's Masjid at Dholka | 44 |

| XXIV. Door to the Court of Hila! Khan Qazi's Masjid at Dholka | 46 |

| XXV. Central Mihrab in Bilal Khan Qazi's Masjid at Dholka, in Gujarat | 48 |

| XXVI. Central Mihrab of the Jami Masjid at Dholka | 50 |

| XXVII. and XXVIII. Panels on the Front Wall of the [ami Masjid at Ahmadabad | 52 |

| XXIX. One of the Marble Tombs of the Queens of Ahmad Shah at Ahmadabad | 56 |

| XXX. Hindu Entrance to the Courtyard of the Tanka Masjid at Dholka | 58 |

| XXXI. Iron Mountings from Shah Karim's Tomb and Mihtar-i Mahall | 60 |

| XXXII. Half Inner Doorway and Outer Door, Mihtar-i Mahall | 62 |

| XXXIII. Stone Ceiling Panels from the Ibrahim Rauza, Bijapur | 64 |

| XXXIV. Door from the Ibrahim Rauza at Bijapur | 66 |

| XXXV. Ceiling in Stucco from the Chhota 'Asar Mosque at Bijapur | 6.8 |

| XXXVI. Facade Arch in the Chhota 'Asar Mosque, Bijapur | 70 |

| XXXVII. Woodwork Window in the 'Asar Mahal, Bijapur | 72 |

| XXXVIII. Wall Surface Decoration in the Tomb of Shah Karim, Bijapur | 74 |

| XXXIX. to XLIII. Perforated and Stucco Parapets from Bijapur | 76 |

| XLIV. and XLV. Mihrabs from the Jami Masjid at Jaunpur | 82 |

| XLVI. XLVII. and XLVIII. Roof Panels from the [ami Masjid at Jaunpur | 86 |

| XLIX. and L Ceilings in Raised Stucco from a Ruined Palace at Bijapur | 90 |

| LI. Cornice and Bracket from Malikajahan Begum's Mosque at Bijapur | 94 |

| LII. and LIII. Tomb of 'Umar Ibn Ahmad Al-Kazaruni at Kambhay | 96 |

| LIV. Details of Ornament from Various Buildings at Bijapur | 100 |

| LV. Brackets from the Nava-Cumbaz and Kumbhar Masjid at Bijapur | 102 |

| LVI. Ornament from the Chaurasi Gumbaz, Kalpi | 104 |

| LVII. Ornament from the Chaurasi Gumbaz, Kalpi | 106 |

| LVIII. and LIX. Principal Mihrab of the Jami Masjid, Fatehpur Sikri | 108 |

| LX, LXI, LXII, and LXIII. Mihrabs in the Jami' Masjid, Fatehpur Sikri | 112 |

| LXIV. Detail of Patera, Jodh Bai's Palace, Fatehpur Sikri | 118 |

| LXV. Detail, of Ornamented Jali-Balustrades and Panel, Jodh Bai's Palace, Fatehpur Sikri | 120 |

| LXVI. Details of Jali-Balustrade and Screen Work in Hawa Mahal, Jodh Bai's Palace, Fatehpur Sikri | 122 |

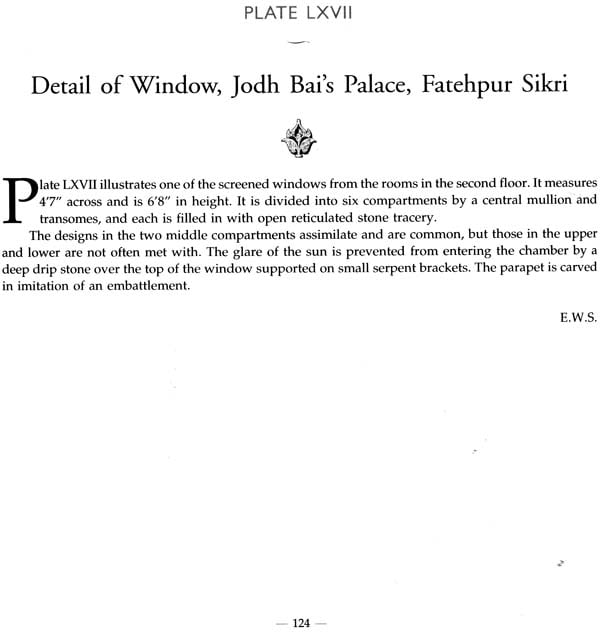

| LXVII. Detail of Window, Jodh Bai's Palace, Fatehpur Sikri | 124 |

| LXVIII. Detail of Shaft in Reception Room, Jodh Bai's Palace, Fatehpur Sikri | 126 |

| LXIX. Detail of Balconette, Jodh Bai's Palace, Fatehpur Sikri | 128 |

| LXX. Fatehpur Sikri: "Jodh Bai's" Palace: Ceiling Over theN orth-West Angle Room on the Ground Floor | 130 |

| LXXI. Fatehpur Sikri: Jodh Bai's Palace: Ceiling over theN orth-East Angle Room on the Ground Floor | 132 |

| LXXII. Fatehpur Sikri: Jodh Bai's Palace: Perforated Red | 134 |

| Sandstone Panel | |

| LXXIII. Fatehpur Sikri: Jodh Bai's Palace: Details of String Mouldings | 136 |

| LXXIV. Fatehpur Sikri: Jodh Bai's Palace (Details of Stone Sills Beneath Wall Recesses) | 138 |

| LXXV. Bracket from Sultana's House, Fathepur Sikri | 140 |

| LXXVI. to LXXVIII. Dado Panel from the Sultana's House, Fatehpur Sikri | 142 |

| LXXVII. Soffit of Drip Stone, Sultana's House, Fatehpur Sikri | 144 |

| LXXVIII. Internal Frieze and Cornice, and External Cornice, South Facade, Sultana's House, Fatehpur Sikri | 146 |

| LXXIX. Ornament from the Turkish Sultana's House, Fatehpur Sikri | 148 |

| LXXX. Fatehpur Sikri: Turkish Sultana's House Carved Dado Panel | 150 |

| LXXXI. Fatehpur Sikri: Turkish Sultana's House (Carved Dado Panel in Red Sandstone) | 152 |

| LXXXII. Verandah Ceiling from the Sultana's House, and Jali Windows from the" Ankh Machaoli", Fatehpur Sikri | 154 |

| LXXXIII. Fatehpur Sikri: Birbal's House | |

| LXXXIII Fatehpur Sikri: Birbal's House (Details of Dado Panels) | 156 |

| LXXXIV. AND LXXXV. Fathepur Sikri: Birbal's House (Detail of Friezes Around the Interior of the Domes Over the Upper Floor Rooms and of the Bases Beneath the Pilasters) | 158 |

| LXXXVI. Fatehpur Sikri: Birbal's House (The North Porch-Details of Archway over the Entrance) | 162 |

| LXXXVII. Fatehpur Sikri: Birbal's House (Detail of Wainscotted Walls in the Upper Rooms) | 164 |

| LXXXVIII. to XCIII. Fatehpur Sikri: Rajah Birbal's House (Wall Recesses, Carved Panels, and Borders) | 166 |

| XCIV.to XCVI. Fatehpur Sikri: Diwan-i-Khas Detail of Pedestal, Base, and Shaft of the Column in the Centre of the Chamber | 174 |

| XCVII. Fatehpur Sikri: Salim Chishti's Tomb (Entrance from the Ambulatory to the Cenotaph Chamber) | 178 |

| XCVIII. and XCIX. Fatehpur Sikri: Salim Chisti's Tomb (Detail of the Porch Columns, and Brackets Supporting Eaves Round the Outer Sides of the Tomb) | 180 |

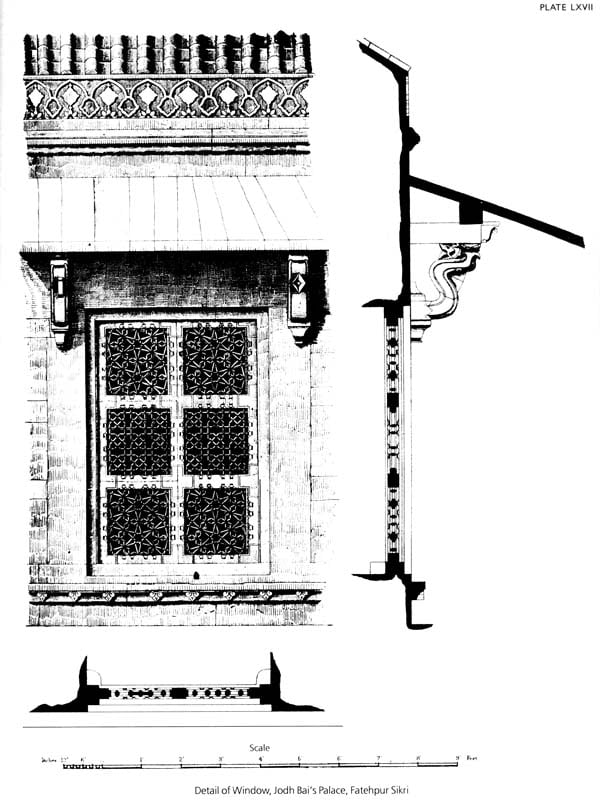

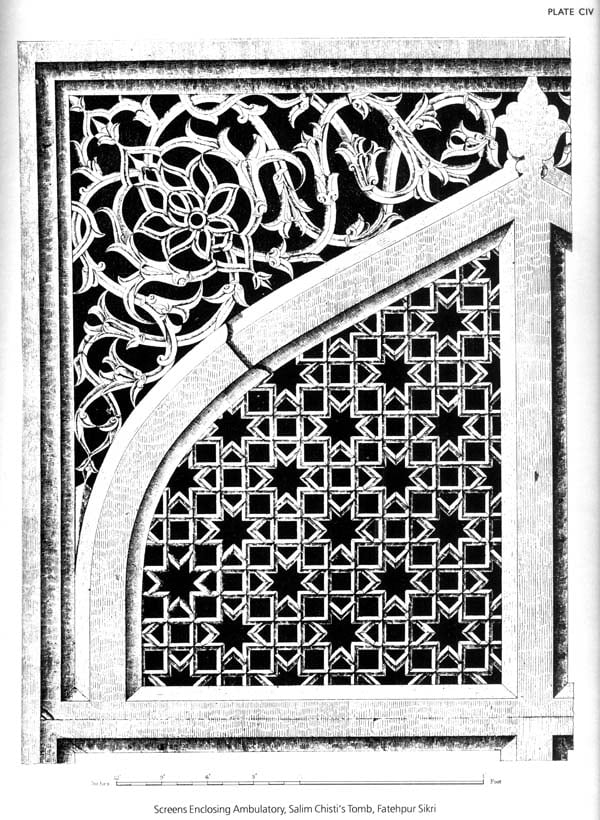

| C. to CIV. Fatehpur Sikri: Salim Chishti's Tomb (Marble Screens Enclosing the Ambulatory) | 184 |

| CV. and CVI. Fatehpur Sikri: Islam Khan's Tomb (Details of Verandah Screens) | 190 |

| CVII. Fatehpur Sikri: The Zanana Rauza (Details of Screen-Work) | 194 |

| CVIII. Fatehpur Sikri: Astrologer's Seat (Detail of Base of Shaft) | 196 |

| CIX. to CXI. Gingee Fort, South Arcot | 198 |

| CXII. and CXIII. Windows from the' Asar Mahal, Bijapur | 202 |

| CXIV. Chaurasi Gumbaz, Kalpi, North-Western Provinces (Detail of One of the Upper Panels on the North Facade) | 206 |

| CXV. Door from the Fort at Hyderabad, Sind | 208 |

| CXVI Perforated Terracotta Window from a Tomb at Sehwan, Sind | 210 |

| CXVII. and CXVIII. Mihrab from Ruined Mosque at Erandol, Khandesh | 212 |

| CXIX. Part of Facade in Wood Carving from a House at Srigunda, Ahmadnagar District, Bombay | 216 |

| CXX, CXXI, and CXXII. Tomb of the Late Navab at Pathari, Central India | 218 |

| CXXIII. Shrine Door of Temple of Samkara at Bheraghat Near Jabalpur | 222 |

| CXXIV. Decorated Ceiling Panels from the Temple of Ambarnath | 224 |

| CXXV. Mihrab in the Jami Masjid at Bharoch | 226 |

| CXXVI. Detail of Stucco Work in Western Wall Makka-ka-Naqal, Bunnur | 228 |

| CXXVII. and CXXVIII. Roof of Pathariya Masjid, Thanesar | 230 |

| CXXIX. Trellised Windows, Tomb of Shaikh Chilli, Thanesar | 232 |

| CXXX. Gateway Near Qazi's Masjid, Sadhaura | 234 |

| CXXXI. Wood-Carving from Bijapur | 236 |

| CXXXII. and CXXXIII. Old Wood Carving | 238 |

| CXXXIV. Details of Doorjamb of Medieeval [aina Temple, Formerly at Agrah | 244 |

| CXXXV. Pilaster of Medieval Ruined Jaina Temple at Atru-Ganeshganj in the Koth State, Eastern Rajputana | 246 |