The Practice and Science of Drawing

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UBA599 |

| Author: | Harold Speed |

| Publisher: | Kalpaz Publications |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2017 |

| ISBN: | 9789351285649 |

| Pages: | 214 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 250 gm |

Book Description

It was not until some time after having passed through the course of training in two of our chief schools of art that the author got any idea of what drawing really meant. What was taught was the faithful copying of a series of objects, beginning with the simplest forms, such as cubes, cones, cylinders, &c (an excellent system to begin with at present in danger of some neglect), after which more complicated objects in plaster of Paris were attempted, and finally copies of the human head and figure posed in suspended animation and supported by blocks, &c. In so far as this was accurately done, all this mechanical training of eye and hand was excellent, but it was not enough. And when with an eye trained to the closest mechanical viaccuracy the author visited the galleries of the Continent and studied the drawings of the old masters, it soon became apparent that either his or their ideas of drawing were all wrong. Very few drawings could be found sufficiently "like the model" to obtain the prize at either of the great schools he had attended. Luckily there was just enough modesty left for him to realise that possibly they were in some mysterious way right and his own training in some way lacking. And so he set to work to try and climb the long uphill road that separates mechanically accurate drawing from artistically accurate drawing.

Now this journey should have been commenced much earlier, and perhaps it was due to his own stupidity that it was not, but it was with a vague idea of saving some students from such wrong-headedness, and possibly straightening out some of the path, that he accepted the invitation to write this book. In writing upon any matter of experience, such as art, the possibilities of misunderstanding are enormous, and one shudders to think of the things that may be put down to one's credit, owing to such misunderstandings. It is like writing about the taste of sugar, you are only likely to be understood by those who have already experienced the flavour, by those who have not, the wildest interpretation will be put upon your words. The written word is nocevarily confined to the things of the understanding because only the understanding has written language; whereas art deals with ideas of a different mental texture, which words can only vaguely suggest. However, there are a large number of people who, although they cannot be said to have experienced in a full sense any works of art, have undoubtedly the impelling desire which a little direction may lead on to a fuller appreciation. And it is to such that books on art are useful. So that although this book is primarily addressed to working students, it is hoped that it may be of interest to that increasing number of people who, tired with the rush and struggle of modern existence, seek refreshment in artistic things. To many such in this country modem art is still a closed book, its point of view is so different from that of the art they have been brought up with, that they refuse to have anything to do with it. Whereas, if they only took the trouble to find out something of the point of view of the modem artist, they would discover new beauties they little suspected.

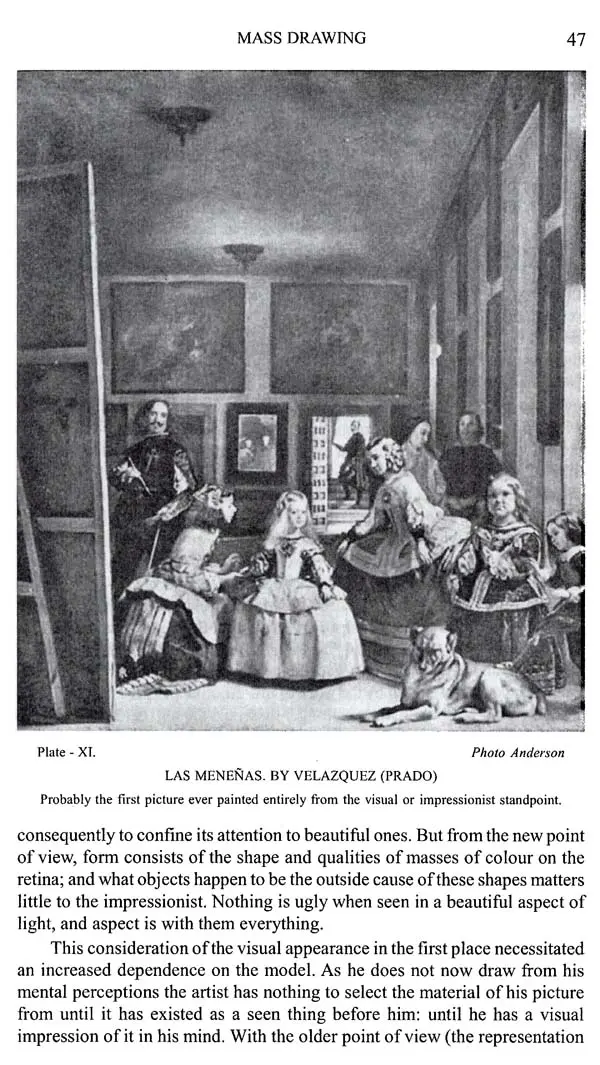

If anybody looks at a picture by Claude Monet from the point of view of a Raphael, he will see nothing but a meaningless jargon of wild paint-strokes. And if anybody looks at a Raphael from the point of view of a Claude Monet, he will, no doubt, only see hard, tinny figures in a setting devoid of any of the lovely atmosphere that always envelops form seen in nature. So wide apart are some of the points of view in painting. In the treatment of form these differences in point of view make for enormous variety in the work. So that no apology need be made for the large amount of space occupied in the following pages by what is usually dismissed as mere theory; but what is in reality the first essential of any good practice in drawing. To have a clear idea of what it is you wish to do, is the first necessity of any successful performance. But our exhibitions are full of works that show how seldom this is the case in art. Works showing much ingenuity and ability, but no artistic brains; pictures that are little more than school studies, exercises in the representation of carefully or carelessly arranged objects, but cold to any artistic intention.

At this time particularly some principles, and a clear intellectual understanding of what it is you are trying to do, are needed. We have no set traditions to guide us. The times when the student accepted the style and traditions of his master and blindly followed them until he found himself, are gone. Such conditions belonged to an age when intercommunication was difficult, and when the artistic horizon was restricted to a single town or province. Science has altered all that, and we may regret the loss of local colour and singleness of aim this growth of art in separate compartments produced, but it is unlikely that such conditions will occur again. Quick means of transit and cheap methods of reproduction have brought the art of the whole world to our doors. Where formerly the artistic food at the disposal of the student was restricted to the few pictures in his vicinity and some prints of others, now there is scarcely a picture of note in the world that is not known to the average student, either from personal inspection at our museums and loan

**Contents and Sample Pages**