Sri Bhakti Sandarbha (Volume 2) The Fifth Book of The Sri Bhagavata-Sandarbhah Also Known as Sri Sat-Sandarbhah By Srila Jiva Gosvami Prabhupada ( (Sanskrit Text, Roman Transliteration and English Translation))

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDI702 |

| Author: | Dr. Satya Narayana Dasa and Bruce Martin |

| Publisher: | Jiva Institute, Vrindavan |

| Language: | (Sanskrit Text, Roman Transliteration and English Translation) |

| Edition: | 2006 |

| ISBN: | 9788187153771 |

| Pages: | 332 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.7" X 5.7 |

| Weight | 670 gm |

Book Description

From The Jacket

Bhakti Sandarbha is the fifth book of the Six Sandarbhas. It offers a thorough analysis of Bhakti, or devotion, on the basis of Srimad Bhagavatam. Jiva Gosvami states that the Bhagavatam prescribes Bhakti as the most efficacious and universal process (abhidheya) for realizing the absolute. Bhakti has never been established as abhidheya so systematically and emphatically as in this book. Earlier Bhakti was generally considered as one among various spiritual processes. Including karma-yoga, jnana-yoga and Astanga-yoga. moreover it was usually regarded as a precursor to jnana, which ultimately leads to liberation. Rarely was Bhakti viewed as an independent process. In contrast to this. Jiva Gosvami asserts that Bhakti is the complete abhidheya, and as such all other processes become futile when bereft of devotion. Other practices have enduring significance only through contact with devotion. Even realization of Brahman is possible only by the grace of bhakti. Bhakti is the most blissful process both in practice and in perfection.

Dr. Satya Narayana Dasa earned his graduate degrees, B. Tech. & M. Tech. In engineering, from IIT Delhi, and worked as a software engineer in USA for a few years.

He gave up a promising career in this field to pursue the inner quest for truth. He studied Sanskrit and the six systems of Indian philosophy under various traditional Gurus in Vrndavana. He also studied the entire range of Gaudiya Vaisnava literature from his Guru. Sri Haridas Sastri. One of the eminent scholars and saints of India.

Dr. Satya Narayana Dasa (PhD. Sanskrit) founded Jiva Institute to promote Vedic culture, philosophy and Ayurveda through education. He regularly gives classes on Gaudiya Vaisnava literature and has authored many books on the subject. He has contributed to the twenty-five volume work brought out by the project of history of Indian science, philosophy and culture.

Bruce Martin has been studying the systems of Indian philosophy. Especially tha of the Chaitanya School for over twenty-five years. Besides English, he is conversant in French, Sanskrit, and Hindi. He has translated and edited several Vaisnava works, including Bhagavad-gita, Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu-bindu, Siksastaka and Manah-siksa.. He is well read in both modern and traditional systems of phi8losophy and is particularly concerned with bringing out the relevance of ancient wisdom tradition for modern practitioners.

Back Of The Book

"If Lord Hari is addressed even unintentionally, He destroys all sins. One in whose heart the Lord Himself is unable to leave because His lotus feet are bound by the rope of love is the topmost of all devotees." (SB. 11.2.55 )

Sridhara Svami comments: "The sage Havi speaks this verse in order to convey the essence of all the definitions of a superlative devotee given previously by him. Lord Hari Himself never abandons the heart of such a devotee. [And how powerful is this Lord who is power less to leave the devotee's heart?] The Lord is He who destroys all sins even if addressed unintentionally or under duress. Why is the Lord powerless to leave the devotee's heart? Because His lotus feet are tied to the devotee's heart with the rope of love. Such a person is called the best of devotees."

Introduction

In volume one, we presented the first part of Bhakti Sandarbha, "Bhakti is the Complete Methodology." Jiva Gosvami began by stating that a methodology to attain the Absolute is necessary to remove the ignorance that is the cause of absorption in the phenomenal. Since bondage is the state of having one's awareness averted from truth, the methodology involves a simple turning of the face to encounter the divine directly. This known as Sammukhya.

From this starting point, Jiva began to explore the criteria for a complete methodology, including the fact that it should be practical for all, be directed towards the complete whole, be independent of all methods, engender an embrace of truth in totality, and be perpetual in nature. Having specified the characteristics of a complete methodology, Jiva ties together the subject of the first chapter by offering a standard to assess true methodology: it must be applicable for all time and space and be verifiable both by direct experience and indirectly. Throughout this discussion, Jiva demonstrates how Bhakti meets this criteria of completeness.

In chapter two Jiva examined the nature of bhakti that makes it the complete methodology. Bhakti removes al that impedes growth and nourishes the being with virtue, awareness and bliss. It is beyond the interactions of material nature, being a specific descent of divine power. Furthermore, it captivates the Absolute and is effective immediately in the offenceless heart.

In chapter three Jiva points out the exclusive nature of pure devotion, that it is without desire for anything extraneous. This indicates an extraordinary feature of complete methodology, that there is nothing to attain by it, because participation in it is itself consummation of the goal. Yet simultaneously, this participation leads to higher and higher degrees of completion through ever-expanding love. Thus bhakti ceases to be a method because it is direct communion. This is true particularly of the nine primary acts of devotion, intrinsically endowed with divine power.

Jiva also analyzes the criteria of eligibility for bhakti as faith, rooted in scriptural understanding and practical surrender. This trust, inspired by divine grace, also suggests the complete nature of bhakti, because the source of eligibility for devotion lies no outside itself. Devotion in the heart of a sage inspires trust, which gives rise to devotion. Devotion is born of devotion. Jiva concludes the first volume by stressing that for this methodology to be truly complete, it must be spontaneous in nature, being a natural expression of the eternal relation between the individual soul and the conscious whole of which it is part. All acts of devotion no inspired by this natural attraction are mere show.

This brings us to this volume, "The Preeminence of the Lord's Devotees," covering part two of Bhakti Sandarbha (Anu 179-213). We find three chapters in this volume: "Devotees as the Cause of Attaining Devotion" (Anu 179-187), "Characteristics of Devotees" (Anu 187-202), and "Devotees as the Cause of Progress on the Path" (Anu 202-213).

In Anuccheda 179 Jiva states that he is beginning a new section that continues until the next section (Anu 214-340) in which the definition of bhakti is stated (Anu 216). This clearly shows the three division of the book. Jiva says that the purpose of this second part is to establish bhakti in a different manner. By showing that bhakti is obtained through the independent will of sages, and by showing the all-encompassing vision of the superlative devotee, saturated with love Jiva again shows the completeness of devotion from yet another perspective.

Jiva says that devotion, endowed with all the characteristics described in volume one, is extremely rare. So the question naturally arises how devotion may be obtained. This is examined in section one of the first chapter (Anu 179-180). The Bhagavata (10.51.53) responds in paradoxical fashion, stating that when the time for a living being's release from material bondage approaches, he or she obtains the association of those established in truth, which fosters a devotional inclination towards the Absolute.

In this statement the impending cessation of material existence is spoken of as if it were the cause of attaining the association of sages, whereas in actuality the opposite is true-that association leads to emancipation. Jiva Gosvami explains that this is a poetic device to emphasize the power of association with those who embody truth. Yet, hidden in these words is a suggestion of bhakti's causeless and sentient nature, as if the immortal nectar of devotion were seeking suitable receptacles to sustain it, then guiding those individuals to the source from which it flows.

While discussing the power of a single act of devotion in the previous volume (Anu 149-164), Jiva pointed out that offences are the only thing that can impede the effectivity of devotion. Similarly, offences obstruct the growth of the devotional temperament born of contact with the sage. Such offences can be removed solely by the grace of the sage.

In section two (Anu 180-185) Jiva discloses a remarkable fact-that the mercy of God is secondary. He defines mercy as a softening of the heart that occurs on contacting the suffering of another. Since Bhagavan is etemally immersed in lila in the transcendent abode, beyond the purview of matter, he never contacts the misery born from the interactions of the phenomenal world. Furthermore, because he is subjugated by the love of his devotees, the devotee's will becomes his will. Thus the devotee is independent in the distribution of mercy, and available to the supplicant. So mercy and devotion flow directly from the devotee.

In section three (Anu 186-187) Jiva discusses the fact that the type of sat-sanga received determines the specific quality of awareness. He thus describes two types of sages: those immersed in nondual awareness and those enraptured in devotion. The latter are divided into three: those who have attained spiritual forms as associates of the Lord, those whose are fully cleansed of material desire, and those who still have a trace of desire, although inactive. Devotees may also be graded by the qualitative and quantitative superiority of their love. Intensity of love determines the depth of a sage's vision of the divine and the completeness of the awareness he or she is able to transmit.

Having explained that devotees are the cause of attaining devotion, Jiva examines the characteristics of devotees in chapter two (Anu 187-202), so that the aspirant can discriminate between varying levels of devotees The first section (Anu 187-190) gives a general description of the superlative, intermediate and neophyte devotees. It is significant that Jiva defines the superlative devotee in terms of awareness, discernible through outward expressions of ecstatic love, since awareness attuned to love is the primary symptom of the topmost devotee. Jiva also describes four distinct visions of the superlative devotee: seeking the Lord directly in all manifestations, perceiving all beings as present within the Lord, viewing all beings as having taken shelter of the Lord, and perceiving one's own love for the Lord in all living beings.

The intermediate devotee is defined exclusively in terms of awareness, since love has not yet taken possession of the self. Unlike the superlative devotee who feels love for all beings, the intermediate devotee feels devotion for the Lord, friendship towards other devotees, compassion for the unaware and indifference towards the inimical. The neophyte is defined primarily in terms of behavior, since awareness remains undeveloped. Such a person worships the deity in the temple with great faith, yet fails to recognize the presence of the Lord in other beings.

In section two (Anu 191-198) Jiva analyzes the symptoms of the superlative devotee in detail. He quotes eight consecutive verses from the Bhagavata (11.2.48-55), which can be taken either collectively, as different symptoms of the topmost devotee, or separately, as defining various grades of superlative devotees. When viewed collectively, these verses serve to particularize the superlative devotee already defined in the previous section.

The essence of all these definitions is found in the final verse, which states that the topmost devotee is one who has bound the Lord within the heart with the rope of love. This is the underlying basis of all other characteristics. Jiva concludes this section by defining the advanced devotee according to the criteria of the path of worship.

In the final section of chapter two (Anu 199-202), Jiva examines the gradations of devotees according to the purity of their practice, quoting a series of five verses from the Bhagavata (11.11.29-33). The first three verse3s define a person endowed with a magnitude of virtue, as the best of sages. Yet, strikingly, Jiva says that his group of verses depicts a lower order spiritual practitioner. In considering the five verses as a whole, Jiva has ascertained that the first three describe a beginning devotee who is surrendered to the Lord but still attacked to prescribed duties and the qualities they engender. Because such a person subordinates devotion to prescribed duty and the development of virtue, his or her devotion is mixed, and hence of a lower grade.

By contrast, the intermediate practitioner, described in the fourth verse, is aware of prescribed and forbidden action as well as the virtue and vice they induce. Yet, he or she sets aside all such considerations, viewing them as obstacles to meditation on the Lord, and engages directly in devotion. This brings up an interesting point: The intermediate practitioner may not even have the qualities of the lower order practitioner described in the previous group of verses, yet he or she is regarded as superior because of the accentuation of devotion. Although engaged in pure devotion, the sense of right and wrong, which is prominent in the intermediate devotee, elicits a reverential attitude that impedes the spontaneous flow of love for the Lord.

This brings us to the final verse in the series, defining the superlative devotee. Again the verse is paradoxical, stating that the best of devotees may not even be aware of the Lord's pervasiveness, his identity as the Soul of all beings, and the spiritual nature of which he is constituted. Yet the preeminence of such a devotee lies in the exclusivity of devotion.

By exclusivity (ananya-bhava), Jiva refers to the establishment of foundational love for the Lord within the heart, with a specific character amongst the moods of servitorship, friendship, parental affection and amorous love. Because love of this nature transcends knowledge, the value of knowledge is discounted for such a devotee. Furthermore, it is the transcendence of knowledge and conventional morality that allows for the spontaneous movement of love. This is what distinguishes the superlative devotee from the intermediate level practitioner. In this section Jiva also describes the divisions of devotees on the path of worship, the differences between a jnani-bhakta and an exclusive devotee, and other divisions of Vaisnavas.

After showing in a generally way that devotees are the cause of devotion in chapter one, and then identifying their characteristics in the second chapter, Jiva discusses in specific manner the instrumentality of devotees along the path of progress in chapter three (Anu 202-213). In section one (Anu 202-205), Jiva describes two paths: the analytical path, based primarily on scriptural deliberation, and the path of taste, based on spontaneous attraction to loving service.

Association with specific devotees nurtures a corresponding faith and attraction for a particular form of the Lord. This interest inspires one to accept an advanced devotee as a spiritual guide, who is fixed both in sound revelation from scripture as well as direct experience of the Absolute. As one hears and deliberates on the scriptural truths received from a guru, one develops faith in God and the practice of devotion, leading to direct realization of the Absolute The path of taste, though sharing some features of the analytical path, is superior, being impelled by spontaneous attraction for the narrations of the Lord. As such it is independent of the scriptural deliberation that characterizes the analytical path.

The final section of the second volume (Anu 206-213) discusses the sravana, siksa and mantra-gurus, elaborating on the topic of acceptance of a teacher from the previous section. The sravana-guru is the instructor from whom one be gins to receive knowledge. The siksa-guru, who is generally the same person as the sravana-guru, offers specific instruction for progress along the path. The mantra-guru is the teacher who plants the seed of devotion in the heart and initiates one into the worship of the Lord. Only one mantra-guru is permissible, except in the case where it is necessary to reject one's guru due to his lack of qualification. Jiva also shows the need for the sravana, siksa and mantra-gurus and the respect for guru on the paths of karma, jnana and bhakti.

Jiva began this volume by stating that he was beginning a new section to establish bhakti in a different manner. In the previous volume he directly discussed the nature and characteristics of bhakti that make it complete methodology. So, if the practice is complete, what about the practitioner? Jiva addresses this question in this volume, showing the completeness of the superlative devotee, the receptacle and transmitter of the divine potency of devotion.

The key points Jiva discusses here are that bhakti has its won independent will, or rather that it moves through the independent will of sages; that quality of association determines quality of awareness, and intensity of love determines depth the vision of the Absolute; that the superlative devotee feels love for all being, seeking the whole with which he or she is enraptured in all of them, and all of them within the whole; that the topmost devotee binds the Lord in the heart with the rope of love, and is engaged in exclusive devotion, founded on a specific relation of love that transcends knowledge and morality; and that the path of taste is highly conducive for those who covet love.

Since the methodology is complete and the devotee in whom bhakti resides is also complete, all that remains for the aspirant is participation in devotion. This topic is taken up in volume three in which Jiva Gosvami defines the intrinsic nature of devotion as seva, or service. He then qualifies devotion, or service, as acts directly constituted of divine power because of their intrinsic connection with the divine. The remainder of the third volume describes the actual practices of devotion under the headings of vaidhi, devotion impelled by injunctions, and raganuga, devotion impelled by spontaneous attraction.

On careful examination it can be seen that Jiva ends this volume on the same point that he concluded the first-that spontaneous devotion is the essence of methodology, transcending all methods. All else is mere show. By pointing out the path of taste as being independent of philosophical deliberation and as being conducive to the attainment of the highest love, all other practices and guidelines are understood as preliminary and as preparing the heart to receive the self-manifest, spontaneous flow of devotion, transmitted through the compassionate grace of sages immersed in the same flow. This is the thread running throughout the text of Bhakti Sandarbha, and which will finally come to full light in volume three in the section on raganuga (Anu 310-338).

| Abbreviations | ix |

| Abbreviations (Devanagari) | xi |

| Introduction | xix |

| | |

| (Anu 179-187) | |

| Devotees are the cause of devotion (Anu 179-180) | 559 |

| Anu 179 Devotional Temperament born of contact with the sage | 559 |

| Offences block the benefit of sanga | 563 |

| A devotee's grace removes offence | 564 |

| Grace is received individually | 565 |

| Anu 180 Obliviousness is removed only by association of sages | 566 |

| The grace of God is secondary (Anu 180-185) | 574 |

| Anu 180 The Lord does not offer grace directly | 574 |

| The Lord's grace is offered through His devotees | 574 |

| Anu 181-184 The sages distribute mercy in accordance with their own will | 574 |

| Anu 185 Ultimate truth is attained only by association of the true devotee | 578 |

| Sat-sanga determines the specific quality of awareness (Anu 186-187) | 584 |

| Anu 186 Two types of sages | 584 |

| Anu 187 Three types of realized devotees | 585 |

| Qualitative and quantitative superiority of love | 587 |

| | |

| | |

| Superlative, intermediate and neophyte devotees (Anu 187-190) | 597 |

| Anu 187 Investigation into the characteristics of devotees | 597 |

| Anu 188 Awareness of the superlative devotee | 598 |

| Brahma-jnana does not fit the criteria of devotion | 601 |

| Anu 189 Awareness of the intermediate devotee | 602 |

| Additional Characteristics of the superlative devotee | 603 |

| Anu 190 Behavior and mentality of the neophyte | 605 |

| Symptoms of the superlative devotee (Anu 191-198) | 616 |

| Anu 191 Unencumbered by the senses | 616 |

| Anu 192 Freedom from the perturbation of physical nature | 617 |

| Anu 193 Freedom from desire | 618 |

| Anu 194 Non-identification with the body | 618 |

| Anu 195 Freedom from material distinctions | 619 |

| Anu 196 Unhampered remembrance | 619 |

| Anu 197 Absolute purity of heart | 620 |

| Anu 198 Binding the Lord with love | 621 |

| All symptoms included within love | 622 |

| Gradations of superlative devotees | 624 |

| The advanced devotee on the path of worship | 625 |

| Five categories of knowledge | 626 |

| Gradations of devotees according to the purity of practice (Anu 199-202) | 638 |

| Anu 199 Lower-order devotees engage in mixed devotion | 639 |

| Anu 200 Intermediate devotees engage in reverential devotion | 641 |

| Divisions of devotees on the path of worship | 645 |

| Anu 201 Superlative devotees worship with exclusive love | 645 |

| The jnani-bhakta and the exclusive devotee | 646 |

| The significance of grounding in exclusive love | 649 |

| Anu 202 Other divisions of Vaisnavas | 650 |

| | |

| Anu 202-213 | |

| Preliminary steps leading to true worship | |

| (Anu 202-205) | 668 |

| Anu 202 The analytical path | 668 |

| The path of taste | 670 |

| Attraction towards a particular form of the Lord. | 672 |

| Acceptance of a teacher | 672 |

| Anu 203 Teachers with and without attachment | 673 |

| Anu 204 Hearing, with and without attachment | 673 |

| Anu 205 Faith in bhajana | 677 |

| Sravana, siksa and mantra gurus (Anu 206-213) | 678 |

| Anu 206 The sravana-guru and siksa-guru are generally the same | 678 |

| Anu 207 Only one mantra-guru is permissible | 679 |

| Anu 208 The need for a sravana-guru | 680 |

| Anu 209 The need for a siksa-guru | 681 |

| Anu 211 Respect for guru on the path of karma | 682 |

| Anu 212 Respect for guru on the path of jnana | 683 |

| Anu 213 Respect for guru on the path on bhakti | 683 |

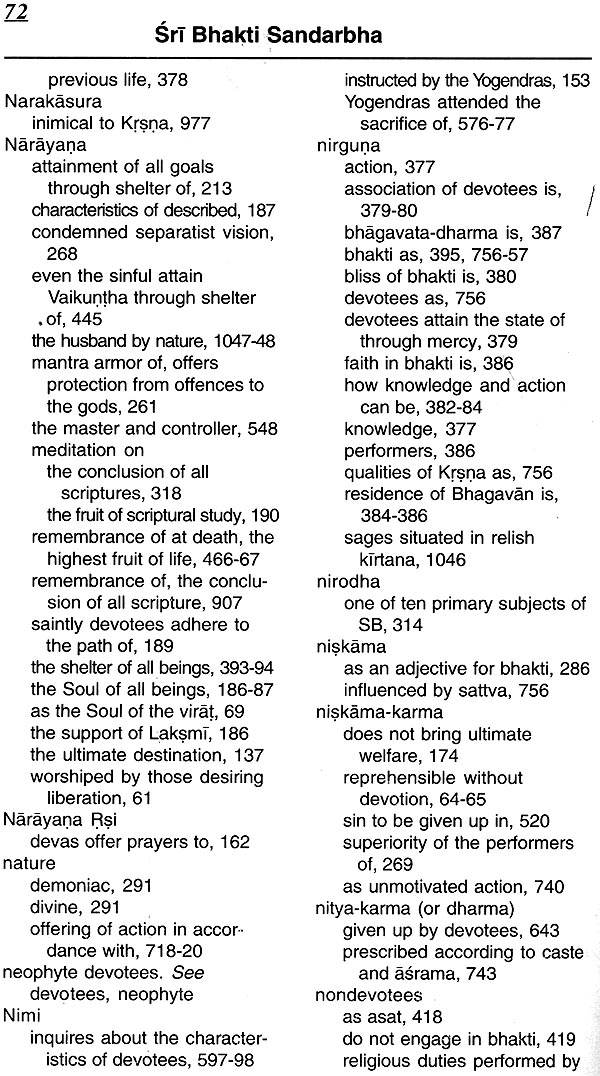

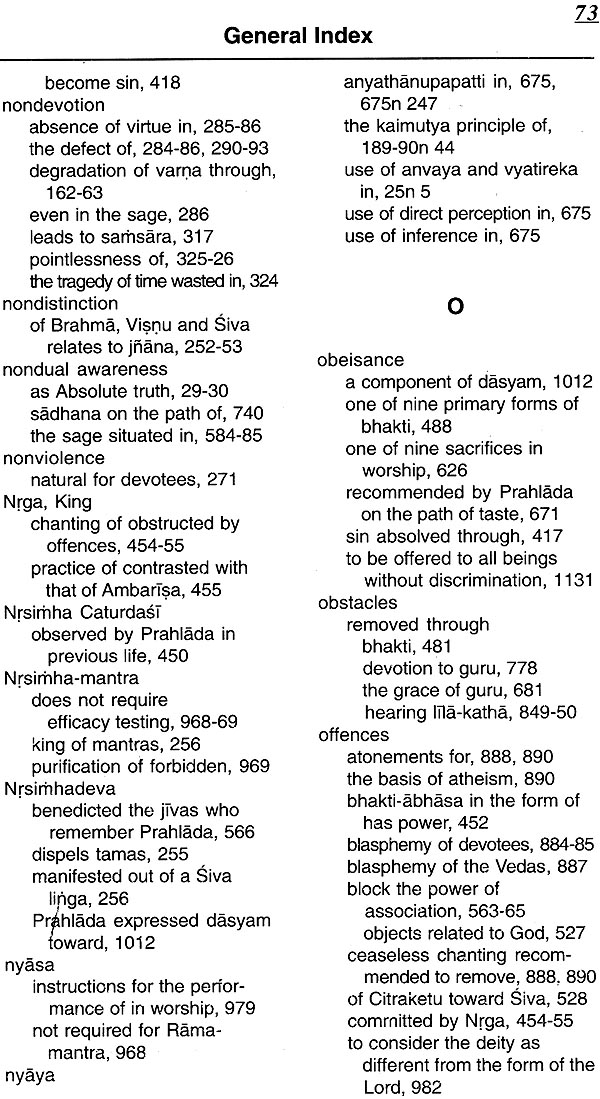

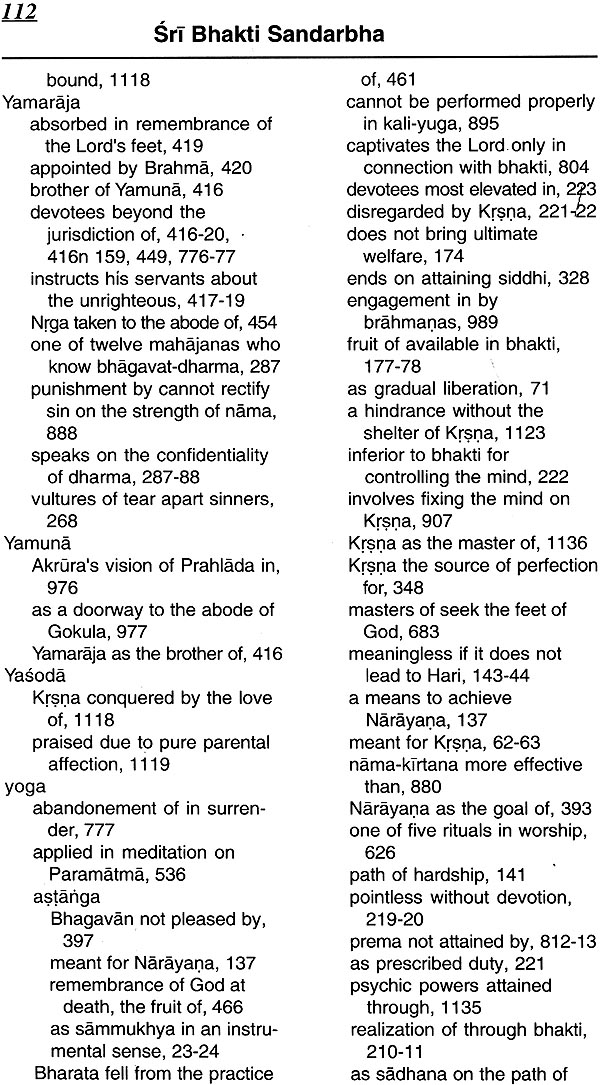

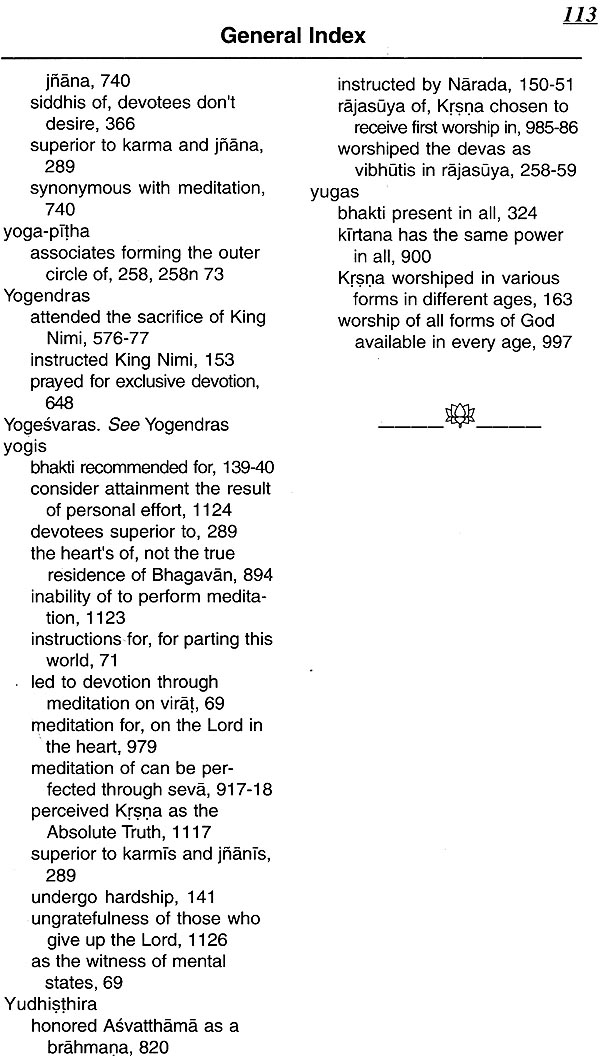

| General Index | 1 |

| Verse Index | 115 |

| Glossary | 141 |