The Story of Swami Rama (The Poet Monk of India)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAQ731 |

| Author: | Puran Singh |

| Publisher: | Swami Rama Tirtha Pratisthan, Lucknow |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2013 |

| Pages: | 279 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 300 gm |

Book Description

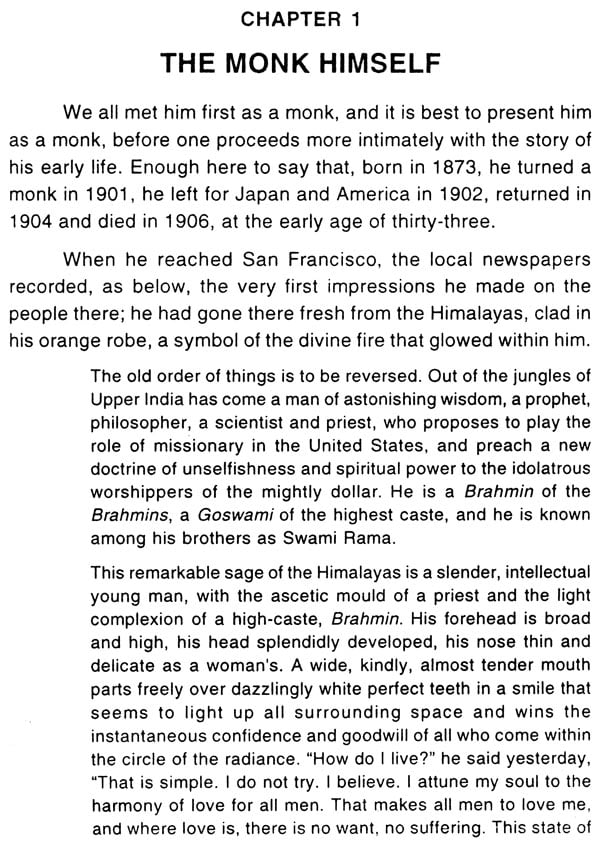

What can be the materials for the biography of a man who was silent on the secret of his joyous life like a lotus that springs up from its humble hidden birth-place, and bursts forth into the glory of its own blossom? And what can be his biography but that whoever happened to see him, a flower amongst men, stood for a while, looking at him, and having looked at him full, went past him, deeply suspecting the existence of golden lands beyond this physical life, whose mystic glimpses shone on his smiling face. This full blown lotus refused to give any further details of the story of his life, though much to the agitation of many a soul, he kept on flaunting the perfume of his soul in air.

Swami Rama was essentially an apostle of the life of the spirit, whose daily food was the Samaran of the name of God-OM. All who knew him saw that he was one who had lost himself in the Lord. His repetition of this spiritual Mantram sounded like a river of song flowing out of him. It is written that this Samaran is assuredly a sign of inspiration; it is God's favour. Swami Rama had completely disentangled himself from the meshes of the world-net and soared like a bird in the higher skies.

A rough pencil-sketch of this inspired personality with whom I first came in contact at Tokyo is given in the following pages in the form of impressions, as it is evidently impossible to trace an authentic history of the development of his mind and his secret love-making with Krishna, God.

It was quite natural for him to rise to the heights of love and call to himself all so feelingly-"I am He,""I am God". But this call in his case was more devotional than philosophical. The stormy passion of Swami Rama, his tears of ecstasy, his poetic joys with beauty, his lyrical realisation of unity with the people who came around him, his broad human sympathy - were all quite different from the dry, academic, wooden, unmoving, rigid indifference of a so-called Vedantic philosopher; his little heart beat in harmony with the rhythm of life itself and the sorrow and joy alike of humanity were his own.

One who would look more closely into his writings would find that the term "Vedanta" as used by Swami Rama has a meaning different from what is generally given to it; it is more or less his own devotin to Krishna or God-Self, blazing up into songs of pantheistic colour. The spirit of his Vedanta, however, was fed by the spirit of the Punjab of Guru Gobind Singh, and further strengthened by the songs of self-affirmation of the adepts like Shams Tabrez and other Indian Masters. All that contributed to the continuous burning of the inner flame of his divine life, he made his own. He used the literature of the whole world-East and West-for winning the inner freedom for himself. His "Aliph"-an Urdu periodical that he issued from Lahore, was the chief vehicle of his rhapsodic writings in which he set in his gem-like collections from Persian, Punjabee, English and Sanskrit literatures. It is the characteristic symbol of his all-embracing mind, his keen feeling of oneness with the past and the future.

He sinks his sentences into tears. He drowns his thoughts in ecstatic cries. He disarms criticism by tenderly diffusing himself into the being of his critic. He wins his enemies by a song of love in which he calls him his own self. He enchants the very air around himself with his bird-like speech that was all poetry, all music. His body was a lake which trembled seeing the Sun enter into its depths. He confounds logic by his divine madness. He contradicts himself in a thousand ways in his self-intoxication which alone is both his creed and religion.

It is sometime difficult to follow him, for one needs the madness of his joy, his glowing passion and his inspiration to rise above all imperfections of all such expressions of the Inexpressible.

He is concerned with the joy of it all, with being God and with nothing else. No doubt, this man tried to give the secret of his success, but whatever he wished to say was blown away like a dry autumn leaf in the tempest of his own bosom and he ended in screams and cries! A truly eloquent apostle of the Life of the Spirit! He pitched himself against the half-life of disbelief and fear. He said, "I see fractions of men, not men. I wish men were whole. Wholeness is holiness."

As a student he worked against stupendous odds with the will of a conqueror, with the devotion of a Satee-woman and with the labour of a galley-slave. Though hungry he would rather deny himself an extra loaf of bread and buy instead more oil for his midnight lamp. And for years, his hunger for knowledge was divine.

As a poet he ran wild and naked with the joy of his feelings as he saw them welling up, swallowing in silence the glory of the Pure. He would bare his body and lie senseless in the open for hours to be bathed by the Sun, to be wiped by the winds. He lived with the poetic spirit of Nature, and he was on terms of great intimacy with her. He would not sit to shape his gold or set his gems or polish his rubies into any complex work of art. It seems his thoughts and feelings in their original shape and colour, had in them the perfection of soul. Never mind the outward forms! His art was simple; it concerned itself with the creation of joy wither himself and in others. With Hafiz and Omar Khyam he sat in the Sacred Tavern of his brother-mystics drinking cups of wine one after another. Tipsy and self-oblivious, he saw God everywhere.

We met Mr. Puran Singh for the first time in Japan. He was a Sikh by birth and was sent there (as far as we learned) by the Sikh community for study. But the rigidity which makes one narrow-minded had not yet dawned to spoil the natural beauty of his mind. He was a young man, susceptible to all influences, unorthodox and highly emotional. His features - both physical and mental-at that time stood in clear contrast to those in riper age when, as generally happens, they were not only set but hardened. He had lost the keen and clear vision of youth and looked with set glasses.

He wrote "The Story of Rama" in his later age. Even then, at places, we catch a glimpse of his younger golden days, when he soars like a lark; but his conclusions do not have the same freshness of view. They are coloured by his old-age rigidity, and show that their author is a devout Sikh. Every review depends on our view, and how nice it were if he did not use any glass even in his later age.

In Sikhism it is firmly believed that no person can improve, sustain inspiration and get salvation without a guru (any higher mystic personality). That is why Mr. Puran remarks again and again in his 'Story' that "Swami Rama, in the burst of his inspiration, forgot that, as he was a student all his life, he had to be a disciple too all his life."

All of us stand on a common platform so far as the necessity of a guru is concerned, but we have to make an end of the guru sooner or later. A guru is only a means to an end, not an end in itself. And the law is that if we do not make an end of the means at the proper time, the means will make an end of us. The ladder is supplied to us to go up, and if we stick to it even when we have reached the top, it will surely bring us down. It is as true in our spiritual advancement as in our educational career. No doubt, a true scholar is ever a student, but a time comes when dependence becomes a sin. When we consider the means to be an end, it becomes idolatory and bans all our real progress. A fruit must stick to a branch before it can be ripe, but when it is once ripe it is against the law of nature for it to remain there. If a child remains in the womb of his mother more than a fixed period, it means death. The same law holds good everywhere.

We require a higher guru, the higher we climb; but when we reach the top, with no intention of coming down, all comparatives cease. All human agencies require supply, for they are exhausted; but how can there be any exhaustion, when one becomes One? There is neither income nor expenditure, neither gain nor loss, neither addition nor subtraction in the Sat-chit-Anand. How can then such a soul suffer loss, which is a contradiction in itself? How can such a soul preach 'away his own personal ecstasy to the world around? How can he require "any living faqir of God-consciousness greater than himself to help him subjectively" when he is in direct communion with the original source of Bliss and Energy? This is a point which requires an unbiased and full thought.

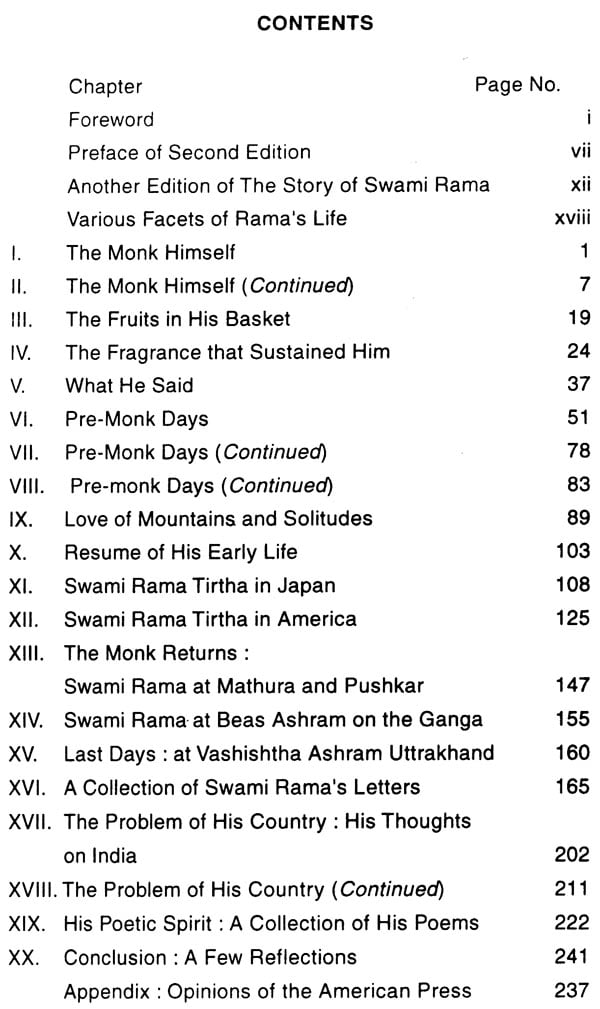

**Contents and Sample Pages**