Three Sanskrit lighter Delights (An Old & Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAQ513 |

| Author: | C.C Mehta |

| Publisher: | The Mahraja Sayajirao University of Barodra |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1969 |

| Pages: | 43 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 7.00 inch |

| Weight | 940 gm |

Book Description

It is exhilarating to observe the opening of new paths of thought and awareness where not long ago barriers obstructed our free passage. In what measure mankind actually progress is hard to say but at least horizons are to-day expanding on every side. Though new prejudices arise, old fall though there is, clearly, much of which we are ignorant where urgent conditions clamor for knowledge, old areas of ignorance disappear before the light of modern research. This is true both within countries and in the inter-course between them. People sometimes forget that the expansive process operates almost as strongly within the humanities as within the sciences. Especially in the humanities we tend to outgrow old pre-conceptions and provincialisms. This proved conspicuously true in the world of literature in general and of the theatre in particular. For most of us, until Professor Mehta's book appeared, its subject remained as unknown as the opposite side of the moon. Culture both in its national and international aspects takes on especially new phases in India.

Scholarship and publication in India turn eagerly to parts of the native literature long slighted, at length brought happily into public view. This holds notably true for the field of classical comedy. For centuries attention had focussed much too severely on acknowledged master-pieces by Kalidasa, Bhavabhuti and their peers. Even that great and massive comedy, The Clay Cart, was, as now generally admitted, under-estimated in Indian criticism. To-day the outlook broadens. Similarly, what appears a new phase in studies bring English and the Indian languages into contact has dawned rather sur prisingly after Indian independence from Great Britian. Far more books in English than ever before are printed in India; far more Indian literature read in English outside India. Translations in both directions are multiplied. Especially with the much- enlarged contacts between India and the United States a new era arises, relatively unvexed by political prejudice and tension. Culturally, it seems, we are aware of a rapidly expanding universe.

May I turn somewhat abruptly from the impersonal to the personal, justify ing my doing so only because in this instance I may utilize personal experience as a metaphor in comparative literature. For over thirty years my own studies and publications dealt almost exclusively with Western literature and, even more restrictively than that, with British and American fields. Then, more rashly than prudently, perhaps I yielded to what appeared the spirit of the times and for a decade have devoted my studies almost entirely to the Asian field. Possibly it was on this account that I have been asked to write this foreword to a book that is dedicated in its subject-matter to India, that was conceived in my native country, America, and is, happily, born on its native soil. Professor Mehta uses the English language with much art and eloquence, addressing readers alike in East and West. He brings hitherto almost unknown treasures of ancient India to modern readers in the most disparate sections of the globe. How generous and expansive this gesture is! How much he is to be commended for the breadth of his activity, that proves him a scholar in accord with the finest and most powerful ideals of twentieth-century learning Such scholars are still too few. May their kind increase, to the greater cordiality of mankind To turn to the specific subject-matter of his book. One is reminded, to begin with, that one of the richest sections of the drama of the Orient is its classical comedy and that this has been thus far most unhappily overlooked. This is evident, for example, in respect to Japan no less than to India. The Japanese comic form, the kyogen, is, at least in my own opinion, one of the most inspired forms of comedy in the history of the world's theatre. Yet it has been slighted in Japan itself and almost wholly overlooked until the most recent days by western students. Where Indian studies are concerned, a similar neglect has been equally striking. To be sure, a few scholars have written illuminatingly on the comic element in the more serious Sanskrit plays, as G. K. Bhat in his study of the traditional humourous character, the Vidushaka. A few lighter plays by the great masters, as Kalidasa's Malavikagnimitra, have been produced with a fair frequency and success, indicating the rich possibilities. But on the whole activity is meagre. It must be confessed, of course, that relatively few Sanskrit comedies are today known to survive. But in a clearly disproportionate measure the overwhelming favour has fallen on the serious, mythological, epic or romantic dramas, where comedy is present, if at all, only in passages of comic relie, as the rather condescending phrase expresses it. Man's ability to laugh at himself ranks as one of his most amiable qualities and one of those holding most hope for his development of increasingly civilized forms of society. Tragedy has a primitive force, its roots in epic sentiment. Although farce is certainly primitive, much lusty comedy of a very early date actually possesses the main ingredients of high comedy, a truth which it would be, I think, supercilious to deny. It throws the beam of its flashlight into man's egotistical darkness. It shows self-centered man how he appears to his neigh bours-a far different image from that which he instinctively entertains of himself. The very excess of mirth castigates the grotesque excesses of human behaviour. What a sprightly and beautiful thing comedy is! Girdling the earth are salt oceans, symbolical of the reservoirs of our tragic tears. The majesty of these waters is beyond compare. But potable waters are fresh, sparkingly streams and those which, by a benign irony of their own, rise in springs out of the breast of the earth itself It is a major fault of the intellect that it takes too seriously and the comic poet not seriously enough. Man is perpetually betrayed by his vain pomposity.

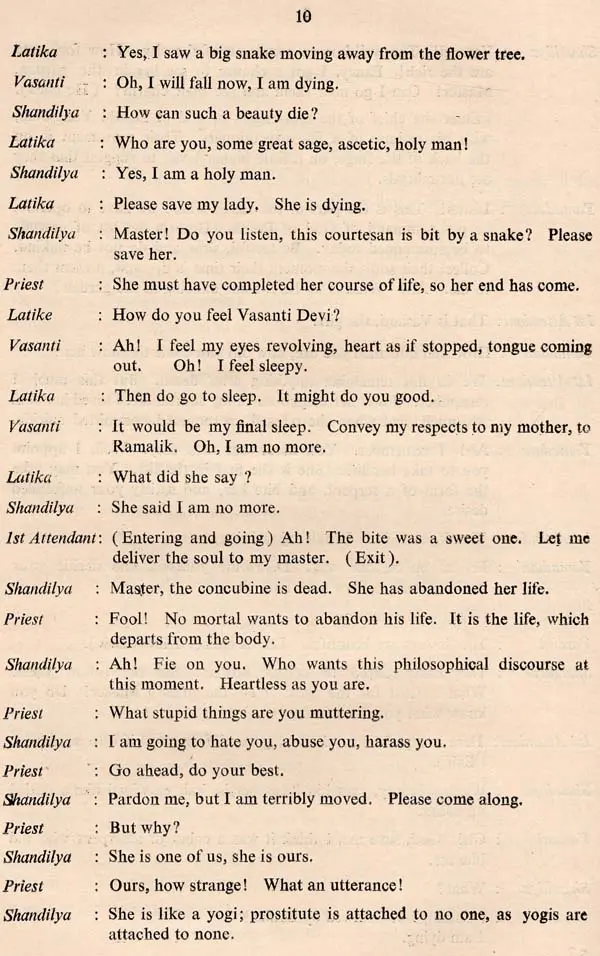

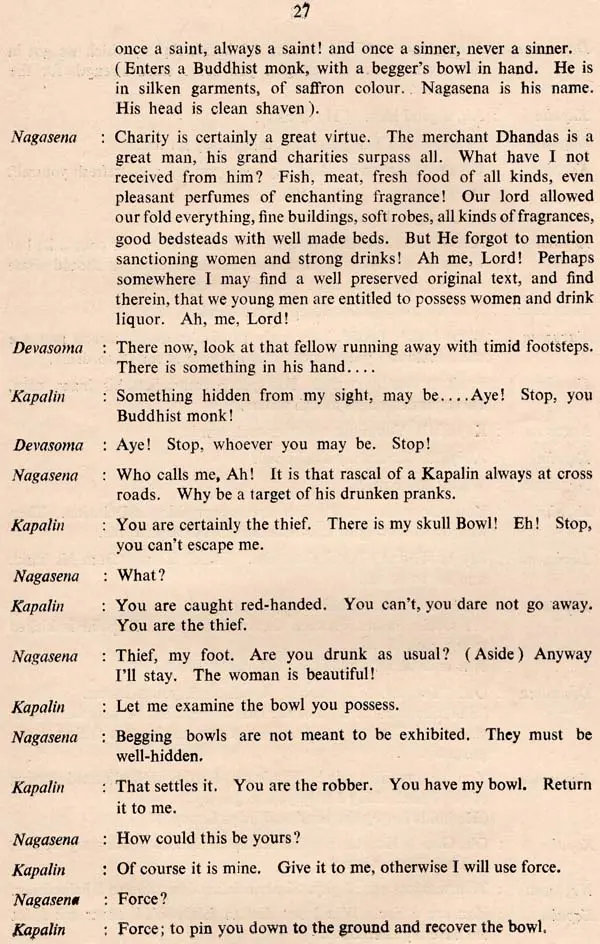

**Contents and Sample Pages**