The Tibetan Tantric Vision

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDJ941 |

| Author: | Krishna Ghosh Della Santina |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2003 |

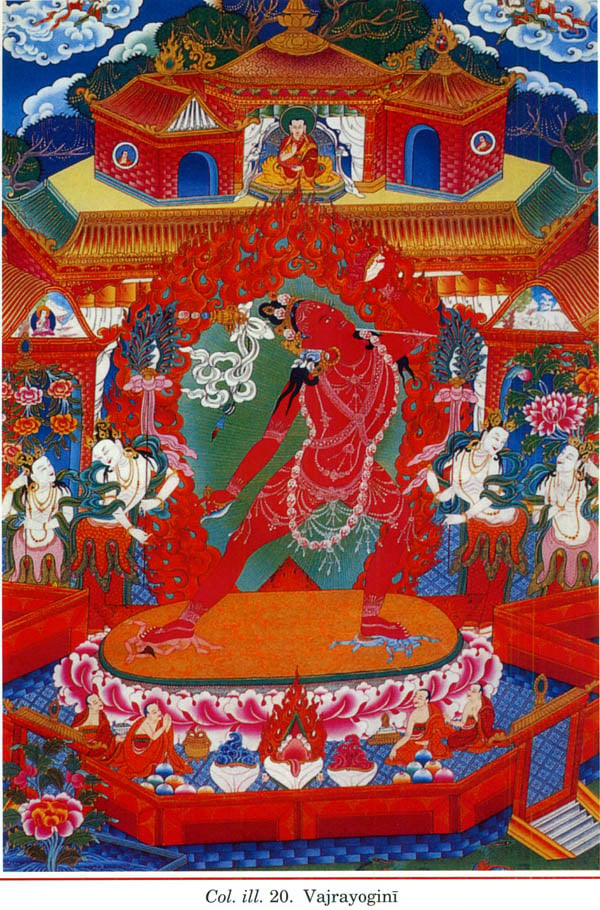

| ISBN: | 8124602271 |

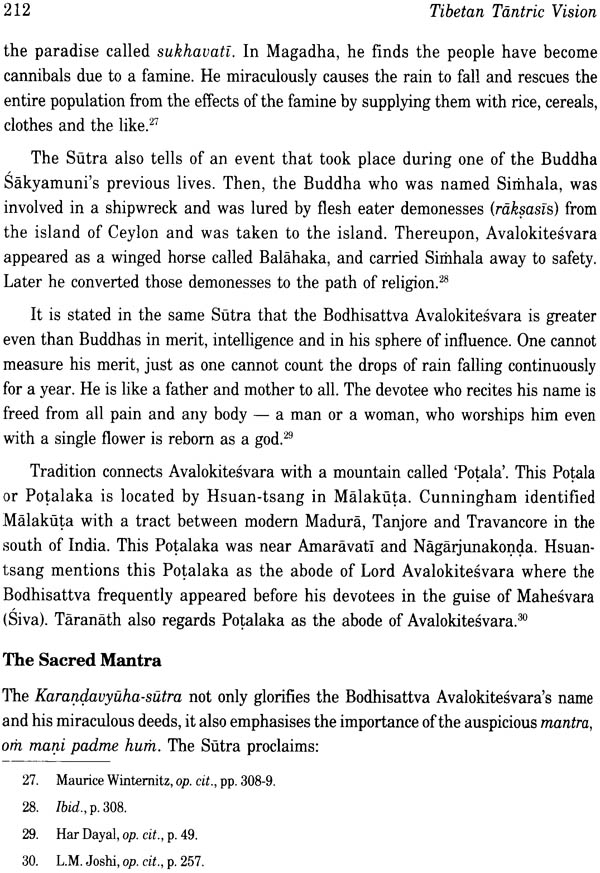

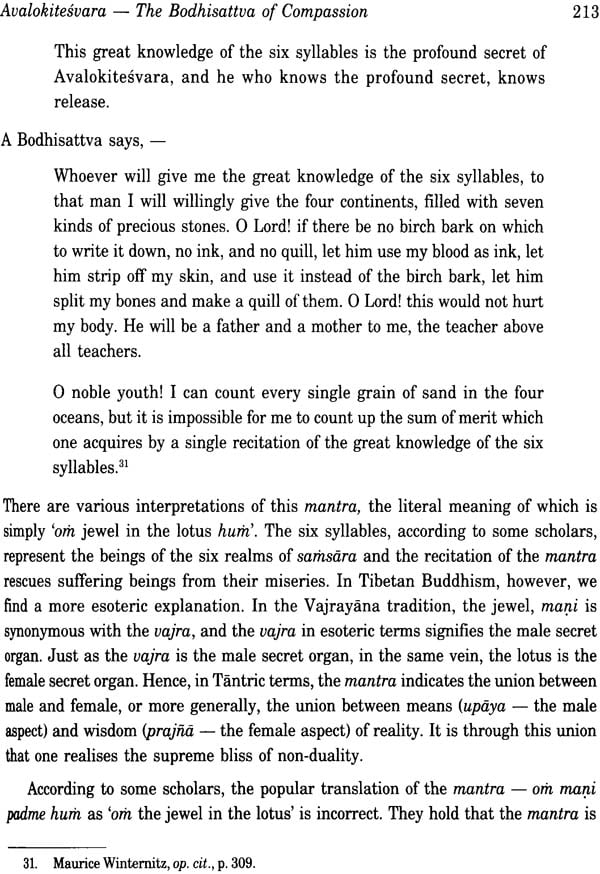

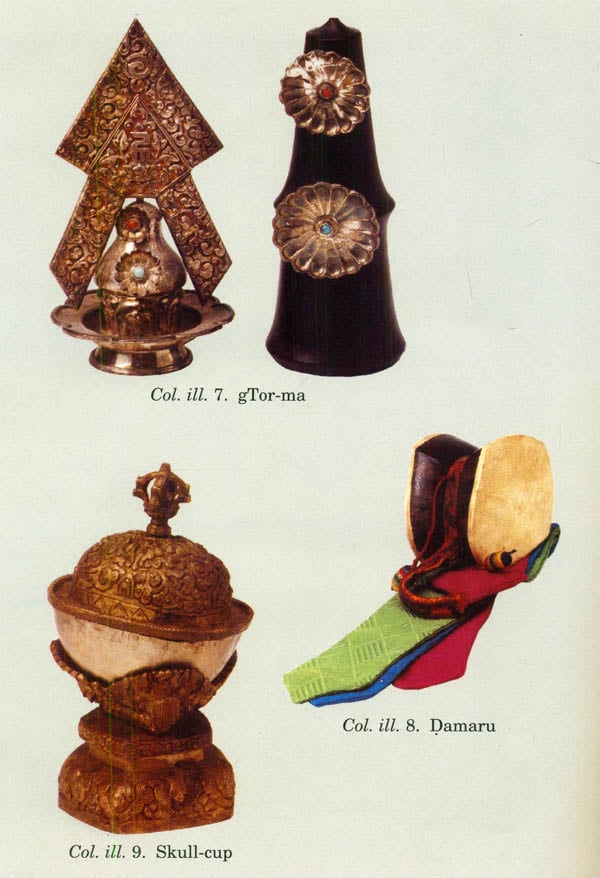

| Pages: | 328 (Color Illustrations: 29 & Black & White Figs: 76) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.6" X 7.1" |

| Weight | 940 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

Tibetan Buddhism has held a place of its own in the Buddhist tradition, having preserved and evolved the religious culture of the Vajrayana, the final phase of Buddhism in India. Within that, the Tibetan Tantric belief has a unique significance and it has made a memorable contribution to the literature on Tibetan Buddhism.

This authoritative work deals with the theory and practice of Tibetan Buddhism in a comprehensive manner. It presents a study of Tibetan Tantricism beginning with an account of the historical, religious and cultural evolution of Tibetan Buddhism and delving into the intricacies of practice of the religion. Dr. Krishna Ghosh discusses the many deities of the tradition as representing a wide range of religious experience - from the primitive to the sublime. She lays bare the complex vision of Tibetan Tantric Buddhist Philosophy and sadhana, clearing it of the obscurantism associated with the belief system for long. The work abounds in illustrations - line drawings and photographs - and has numerous references to original works by Tibetan and other scholars.

The book is written in an easy accessible style to allow a broad range of readers to familiarize themselves with Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. Its penetrating insights into the subject would make it an invaluable work for scholars and practitioners of the tradition.

About the Author

Krishna Ghosh has a B.A. and M.A. in Sanskrit and an M. Litt. and Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies from the University of Delhi. She was traveled widely and has lived in several Buddhist countries. She has been closely associated with the Tibetan community in exile for more than thirty years. Krishna Ghosh has lectured and taught Pali, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Indian religion and Buddhism at many universities and religious centers in Europe, Asia and America.

Preface

BUDDHISM was once a vibrant and thriving religion, which dominated the field of religion on the Indian sub-continent. When it began to decline and eventually all but disappeared from the land of its origin, it took refuge in the Himalayan regions and in the land of snows, Tibet. Following upon its introduction into Tibet, over the course of several centuries, it assumed its own particular form, while not loosing its essential character and spirit. Tibetan Buddhism preserved and extended the religious culture of the Vajrayana, the final development of Buddhism in India. In Tibet, Buddhism flourished under many qualified teachers both from India and Tibet.

Tibet, and Tibetan Buddhism have attracted outsiders from a very early date. There were many people: adventurers, missionaries, civil servants and scholars, who wanted to visit the roof of the world. Among them, there were many who were attracted to Tibetan Buddhism. Consequently, Tibetan Studies became a new field for investigation for many modern scholars.

It has been more that half a century since the Tibetans lost their land and their freedom. The Tibetan Buddhist religion has suffered at the hands of the communist regime in China. The story is not any longer a new one. It has been recounted by many people many times. Tibetans in exile have done their best to maintain their equanimity and to practice their religion under their spiritual leaders and many notable teachers. At the present moment Tibetan Buddhism is no longer remote and isolated. On the contrary, it is open to anyone who is interested in the teachings of the Buddha. Tibetan Buddhism has become very popular among young and old alike all over the world.

I did my Ph.D. on a theme entitled "A Few Tibetan Buddhist Deities", with the Department of Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi, in 1981.

As a result of the tremendous amount of interest in Tibetan Buddhism, sometime ago D.K. Printworld, expressed their interest to bringing out my thesis in the form of a book. The thesis, thus, has undergone major revisions to make it more accessible to a general audience and has been updated thoroughly as well, inasmuch as many years have passed since its first writing. I have rendered Sanskrit and Pali names and terms with diacritical marks. Tibetan names and terms have been given according to orthodox rules of transliteration. At the end of the book, glossaries of Sanskrit and Tibetan terms are included.

I am indebted to many individuals for the successful completion of this project. First and foremost I owe my thanks to my able supervisors from the Department of Buddhist Studies of the University of Delhi, Geshe G, Gyatso and late Miss S. Sengupta for their unfailing help and expert guidance while I was still a research student under them. I owe my sincere gratitude to H.H. Sakya Trizin, T.G. Dhongthog Rinpoche and Geshe Thamcho Yontan for the patient instruction which they gave me.

I would also like to offer my sincere thanks thanks to Professor Lokesh Chandra for giving me permission to reproduce a large number of illustrations which are included in the present book from his Buddhist Iconography.

Thanks are also due to Mr. Jay Goldberg, Mr. Paul Hagstrom and Mr. Yeo Eng Chen for allowing me to include some photographs of thang-ka paintings and ritual objects from their private collections in this book. Last, but not least, I would like to express my gratitude and thanks to Dr. Peter Della Santina whose constant guidance, valuable suggestions and patience helped me to complete this book.

Introduction

The topic that we have chosen as the subject of our study is not without some difficulties and peculiar problems. This is so because the Tibetan Tantric tradition which we have undertaken to study falls within the realm of what may be termed esoteric traditions are required not to reveal the secrets of the tradition except under certain specially prescribed circumstances.

This fact, in itself, hinders the kind of open investigation that might be possible in another area. The Practitioners of the Buddhist Tantric Tradition are no doubt justified in their reticence, for, a careless disclosure of its secrets could weaken the tradition and expose it to misunderstanding and criticism. Moreover, they are genuinely concerned about psychological of Tantric knowledge.

Although scholars can obtain many documented works in Sanskrit and Tibetan languages on Tantra, the difficulty of understanding the Tantric tradition is not lessened by this fact. In this case, mere access to the written word is insufficient, because the languages of Tantra is symbolic rather than explicit, and is commonly designated, intentional language, sandha-bhasa. Therefore, any attempt to understand the Tibetan Tantric vision based just upon the evidence of texts may be misleading.

Many early commentators on Tantra approached the subject with the biased view of an outsider. Moreover, many of these writers on Tantra have overlooked what has been said about the symbolic nature of Tantric language and have assumed that a simple textual study could make Vajrayana understandable to the outsider. They have very often imposed conceptural models borrowed from Western philosophy and the social sciences upon a collection of superficial facts gathered from textual sources.

The works of many older writers on Tantra, suffer from important limitations. They have very often ignored the religious and philosophical contexts of the Tantric tradition.

In the works of a number of the earlier writers on Buddhist Tantra we can easily discern a persistent attempt to designate Tantra as nothing but a degenerate form of Buddhism born out of primitive beliefs and practices. They often dismissed Tantra as nothing but superstitious mumbo-jumbo. Fortunately, although this tendency still persists in some quarters, its credibility has definitely been reduced, and way to a more open and appreciative understanding of the Tantric tradition is now clear.

Once the decision had been taken to adopt a contextual approach, the choice of a perspective that would facilitate a better understanding of our subject became unavoidable. We decided to study the Tibetan Tantric vision within its natural indigenous environment. This approach recommends itself because of its simplicity and directness. Moreover, it holds out the hope of presenting an intelligible description of our subject by means of concepts which are intimately connected with it: historically, culturally and conceptually.

We, therefore, chose to approach the study of the deities of the Tibetan Tantric vision within the threefold context of history, culture, religion and philosophy. In doing so, we have assumed that the deities and practices of the Tibetan Tantric tradition form a part of a complex phenomena which is composed of three principal elements: the History of India and Tibet, the culture of India and Tibet and Mahayana Buddhist religion and philosophy. The adoption of this approach enabled us to study our subject within a context provided by authoritative expositions and exponents of the Tibetan Tantric tradition. In this way, it became possible to present a true picture of Tibetan Tantric vision, which corresponds to the view of Tibetan Buddhists themselves.

We have accepted a pre-modernist view of history wherein the story of persons predominates over the story of events. This view of history naturally from the fact that classical histories upon which we have relied heavily are, in actuality, compilations of the personal histories or hagiographies of a number of outstanding religious and political figures. The traditional accounts of religious and cultural history of Tibet do not attempt to present a comprehensive picture of the course of national and international events including economic, social and political date relating to the periods with which they are concerned. Neither do they attempt to interpret the events which they recount in terms of national or international economic, social, and political forces. None the less, they represent the only authentic accounts of classical Tibetan history available to scholars and so must be given foremost consideration. Moreover, the deficiencies from which these classical histories suffer do not hinder our particular purpose, for we are concerned with phenomena which are primarily cultural and religious.

The information supplied by traditional accounts form, as it were, the raw material with which our study has been constructed. We have attempted to structure these original data by means of the principles and doctrines of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Firstly, because these religious and philosophical principles are accepted by the Tibetan Tantric tradition as representing the fundamental essence of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, and secondly, because our subject lends itself naturally to interpretation in the light of Indian and Tibetan Buddhist religion and philosophy. Indeed it would only be possible to accomplish our twofold objective of presenting an intelligible picture of the deities and practices of the Tibetan Tantric tradition and one, which is in agreement with that given by Tibetan Buddhists themselves if we accepted the structural importance of such religious principles. We have, therefore, structured the historical material available to us by means of some fundamental principles of Mahayana and Tantric Buddhist religion and philosophy.

Finally, we have interpreted the term 'culture' to mean essentially the synthesis of philosophy and history, which is evident in the life of people. Thus, it is that the history and philosophy of people are reflected in the art, music and social customs of the population. For the purposes of our study we shall be principally concerned with the art and iconography and religious practices of a tradition that abstract principles of philosophy are given concrete expression in the lift of the people through symbols and rituals. Hence, a meaningful study of the Tibetan Tantric vision must include an examination of the symbolism of Tibetan Tantric Buddhist iconography and of practices associated with the worship of Tantric deities. Only then will it be possible to determine the nature and function of Tibetan Tantric deities and practices in relation to both Buddhist Tantric philosophy on the one hand and the history of Tibet on the other.

| Preface | v | |

| List of Illustrations | ix | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| 1. | History of Introduction of Buddhism into Tibet | 7 |

| 2. | The Process of Acculturation | 41 |

| 3. | Tibetan Buddhist Art and Iconography | 57 |

| 4. | Religion and Philosophy | 113 |

| 5. | Tshe-ring-mched-Inga (the Five Sisters of Long Life) and bsTan-ma-bcu-gyis (the Twelve Guardian Goddesses) | 131 |

| 6. | The Religious Protector Mahakala | 173 |

| 7. | Avalokitesvara - the Bodhisattva of Compassion | 203 |

| 8. | Tantric Philosophy and Principal Elements of Tantric Buddhism | 229 |

| 9. | The Tantric Path | 251 |

| 10. | The Tantric Sadhana | 267 |

| Conclusion | 281 | |

| Coloured Visuals | 285 | |

| Glossary of Sanskrit Terms | 309 | |

| Select Bibliography | 319 | |

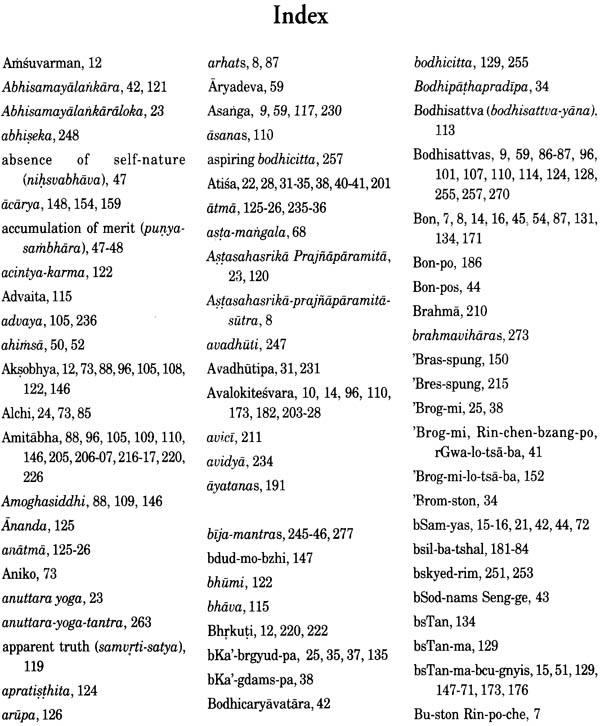

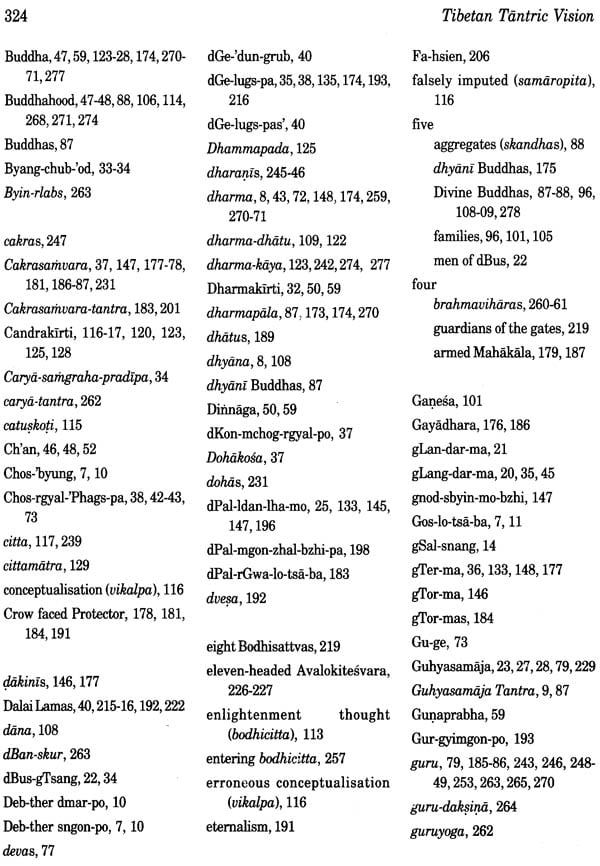

| Index | 323 |