Vishnu Purana (Krishna's Pastimes in the Fifth Canto)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAW108 |

| Publisher: | Ras Bihari Lal and Sons |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2020 |

| ISBN: | 9788184037 |

| Pages: | 342 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 440 gm |

Book Description

The Vishnu Purana is an ancient scripture. It was often cited by the Gosvamins of Vrindavan in their commentaries on the tenth canto of the Bhagavata Purana and was held in high regard by Sankaracarya and Ramanujacarya as well.

Like the Purusa-sukta, the Vishnu purana occasionally expounds panthenism: Nature is a form of God. In addition, all the pastime of Krishna are told in breif, yet with amazing details. The fifth canto has a distinct sweetness and is relished by the connoisseurs.

The Vishnu Purana is as authoritative as the Mahabharata. The tenth canto of Bhagavatam follows canto of Vishnu Purana, which is fully translated here. This short and sweet narration of Krishna pastime appeals to readers of all ages.

The Visnu Purana is a highly authoritative scripture. It is very ancient. The fifth canto therein corresponds to the tenth canto of Bhagavatam (Bhagavata Purana). In their commentaries on the tenth canto, the Gaudiya Vaisnava acaryas, including Sanatana Gosvami, Jiva Gosvami and Visvanatha Cakravarti, often cited verses from the fifth canto of Visnu Purana, especially when Sukadeva skipped some detail in his narration.

The fifth canto of Visnu Purana is the longest of its six cantos, with thirty-eight chapters. The speaker of Visnu Purana is Paragara Muni, the father of Vyasa. The Purana is in fact a long conversation between Parasgara Muni and Maitreya Rsi.

In 2005 in Govardhana, India, His Grace Gopi-parana-dhana Prabhu opened a Sanskrit school, from which the present writer graduated. Gopi-parana-dhana Prabhu’s motive was to turn devotees into translators of Gaudiya Vaisnava scriptures. He gave classes on Jiva Gosvami’s Sat-sandarbha, specifically on Tattva-sandarbha and Bhagavat-sandarbha in order to verify his translations of those, on Bhagavatam, and on the commentaries on Bhagavatam. Moreover, he taught a translation workshop, where he would critique the students’ translations of a text (he selected the Bhagavata-mahatmya of Skanda Purana). And he invited knowledgeable devotees in the field, such as experienced English editors, to train the students. Gopi-parana-dhana Prabhu had a list of Vaisnava titles that he wanted to see translated. One of them was Visnu Purana. He opined that Vaisnavas should have their own translation of this ancient Vedic text.

This Purana is the blueprint from which the entire Bhagavatam evolved. The Padma Purana categorizes the Visnu Purana as a sattvika Purana’ like it categorizes the Bhagavatam. A sattvika Purana is in the highest mode of thinking, meaning Hari (Visnu, Krsna), and not Siva or any other god, is glorified.

Like most other Puranas, the Visnu Purana cannot be easily dated. This is because each Purana consists of material that has grown by numerous accretions over long periods of time, not to mention spurious interpolations. For centuries, ancient Vedic scriptures were communicated verbally before finally being put in writing. Yet most scholars agree that the Visnu Purana and the Bhagavatam are free from spurious content.

According to tradition, Krsna pastimes were rendered in the following scriptures in this chronological order, although the details vary from one scripture to the next: Mahabharata, Visnu Purana, Hari-vamsa (an appendix of Mahabharata), and Bhagavatam. The language in Bhagavatam is much more refined and involves elaborate meters, whereas most of the text in the other scriptures is in the anustup meter. Further, it is interesting to note the differences between the fifth canto of Visnu Purana and the text of Bhagavatam both from the viewpoint of lila (variation in a pastime, and the sequence of pastimes) and from the standpoint of siddhanta (philosophy) (especially regarding Krsna’s disappearance, in chapter 38).

The contrast between these two similar scriptures is also perceivable from the perspective of grammar: In Visnu Purana, the genitive absolute is often used in the sense of the locative absolute, whereas in Bhagavatam this usage is very rare (6.17.26; 8.4.5; 12.6.13: etc.). In other words, the genitive absolute is used although disregard, ordained by rule,’ is not implied. This usage of the genitive absolute is not covered by Panini’s grammar (450 BCE), not to mention subsequent grammars, and is almost never seen outside of these two Puranas. This suggests that the Bhagavatam was composed in the light of Visnu Purana and that the author or authors of Visnu Purana preferred the usage in a different system of grammar, one older than Panini’s school, such as the Aindra school, the archetype of Katantra grammar (50 CE).

In India, the most authoritative scholars held the Visnu Purana in high esteem. In his commentaries on Prasthana-traya (Gita, Veddnta-sitra, and Upanisads), Sankaracarya cited Visnu Purana (Bhagavad-gita-Bhasya 3.37, etc.), but never quoted the Bhdgavatam. In Sri-Bhdsya (4.1.2), Ramanuja Acarya quoted Visnu Purana, but never cited a verse from the Bhagavatam. Sridhara Svami wrote a commentary on Visnu Purana before writing one on Bhdgavatam.

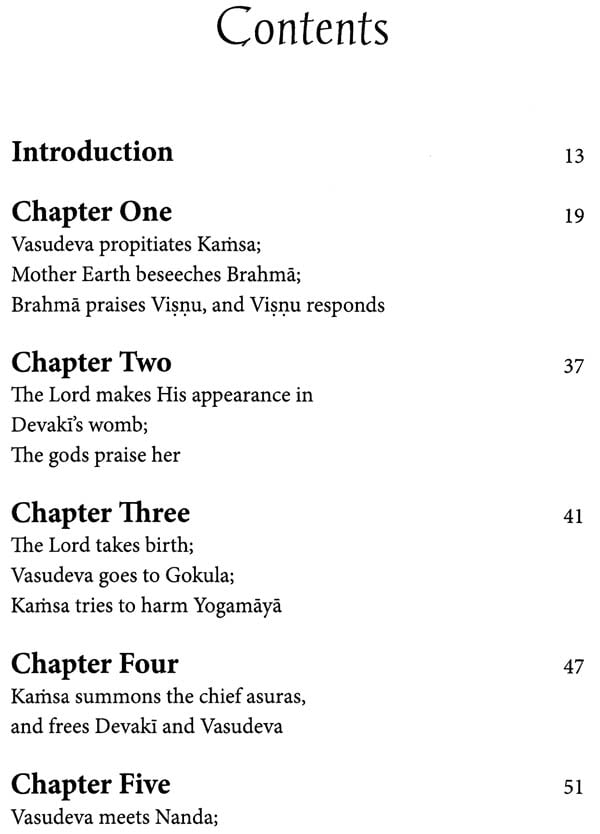

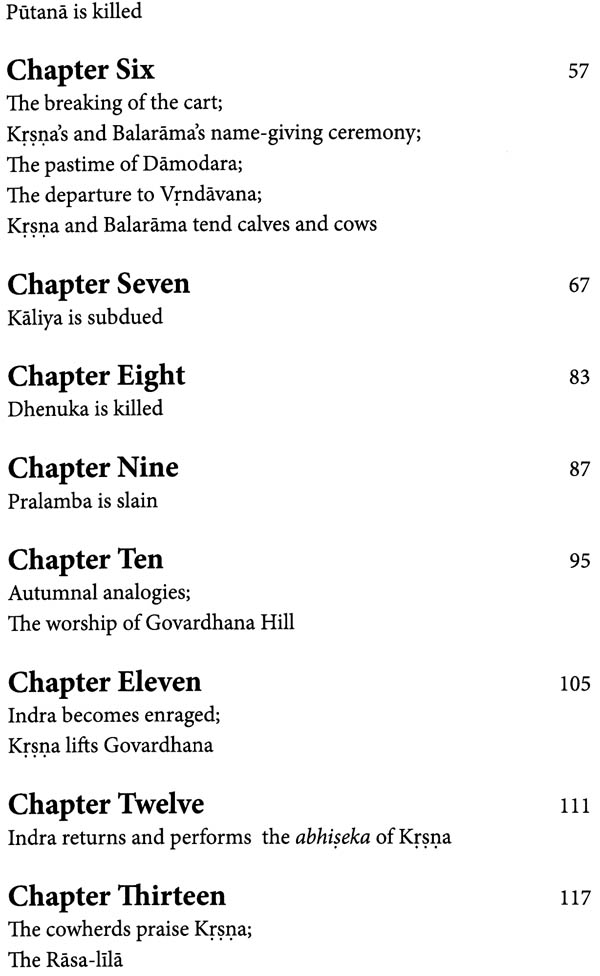

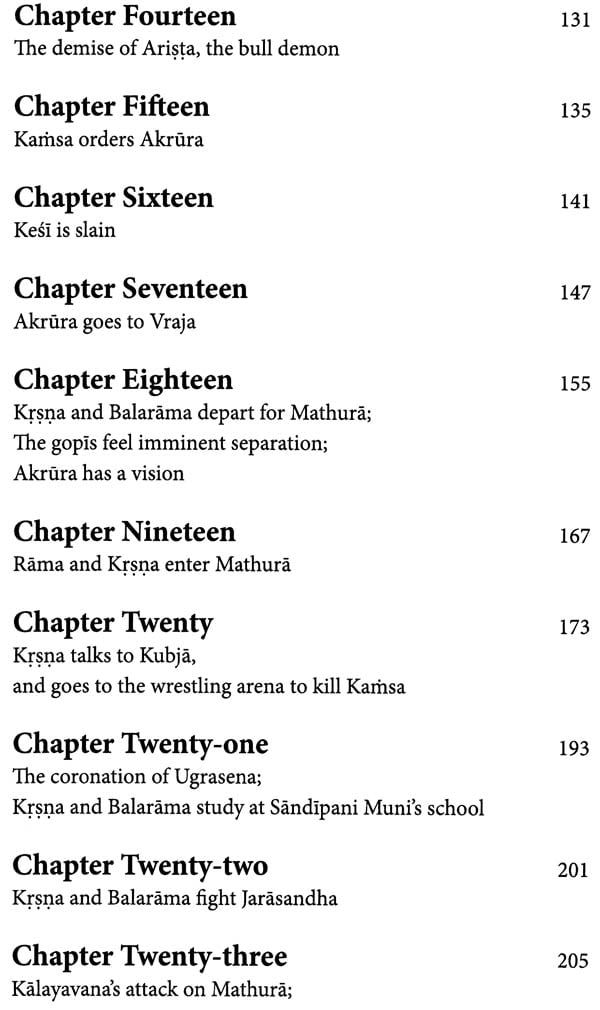

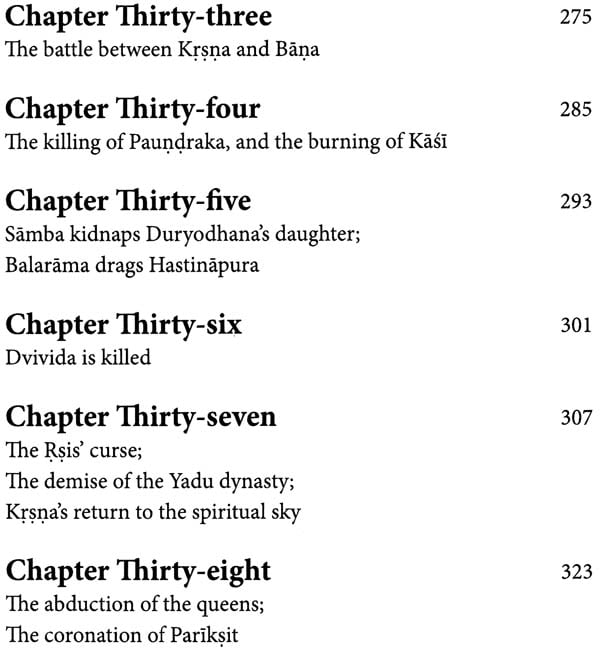

**Contents and Sample Pages**