Women Mystics and Sufi Shrines in India

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAY575 |

| Author: | Kelly Pemberton |

| Publisher: | MUNSHIRAM MANOHARLAL PUBLISHERS PVT LTD |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9788121512855 |

| Pages: | 258 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 10.00 X 6.50 inch |

| Weight | 530 gm |

Book Description

Kelly Pemberton is an Assistant Professor of Religion and Women's Studies at George Washington University and coeditor of Shared Idioms, Sacred Symbols, and the Articulation of Identities ill South Asia. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Ritual Studies, Muslim World, the Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures, and other publications.

Women and Sufi Shrines in Contemporary India

By the time of my second sojourn in the Subcontinent in the summer of 1996, now as a PhD. student at Columbia University, I had decided to investigate the question of contemporary Sufis by looking at a number of shrines in northern and central India. After three months spent traveling in sweltering, dusty government buses from the northwest corner of Rajasthan down through Madhya Pradesh and northeast to Bihar, I had amassed a large body of notes, tape-recorded interviews with Sufi men and women, and experiences I could not have imagined beforehand, but had no clue how to make sense of all this information. After my return to academic life, Professor Jack Hawley suggested, in light of what I had seen and reported to him, that I focus on the question of women's roles in Sufi orders today when I returned to India the following year. The thought of pursuing this topic was daunting.

I had broached the subject of women's participation with most of the Sufis I met that summer, but their responses to "the woman question" were discouraging. While many of them eagerly discussed the subject of female saints! who had lived in the distant past-most often people brought up the example of the eighth-century saint of Basra, Rabbi’s al-'Adawiyya-they were reluctant to discuss the place of women in the Sufi communities to which they themselves belonged. Women, I was repeatedly told, had no significant role to play in Sufism today, except as disciples of a pir or sahib, and women could never become pirs themselves. For some reason I wasn't quite ready to accept these opinions at face value, and what I had seen at three Sufi shrines that summer convinced me that there was a significant gap between what most people said women did at shrines and women's lived experiences. While visiting the town of Ajmer in Rajasthan, I had visited the burial shrine, or dargah, of the thirteenth-century Sufi master Muin al-din Chishti and was introduced by a young teenage boy, a servant of the shrine Ckhadim), to a few of the men-highly placed in the hierarchy of the shrine's functionaries-who claimed descent from the saint. I had been looking for primary sources about the shrine and saint and knew from prior research that the dargah contained a library, of which the nazim dargah, a government-appointed functionary, was in charge. I wasn't able to gain access to the dargah's library or to meet with the nazim dargah, who was out of town at the time. In any case the library was in such a state of disrepair that I would have been unable to use it even if the nazim dargah had consented.

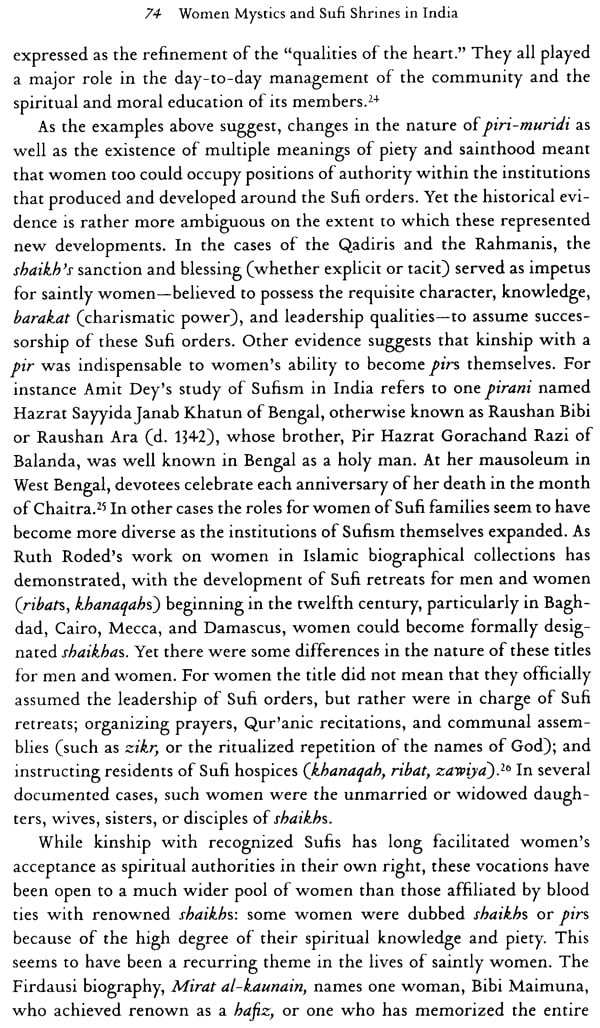

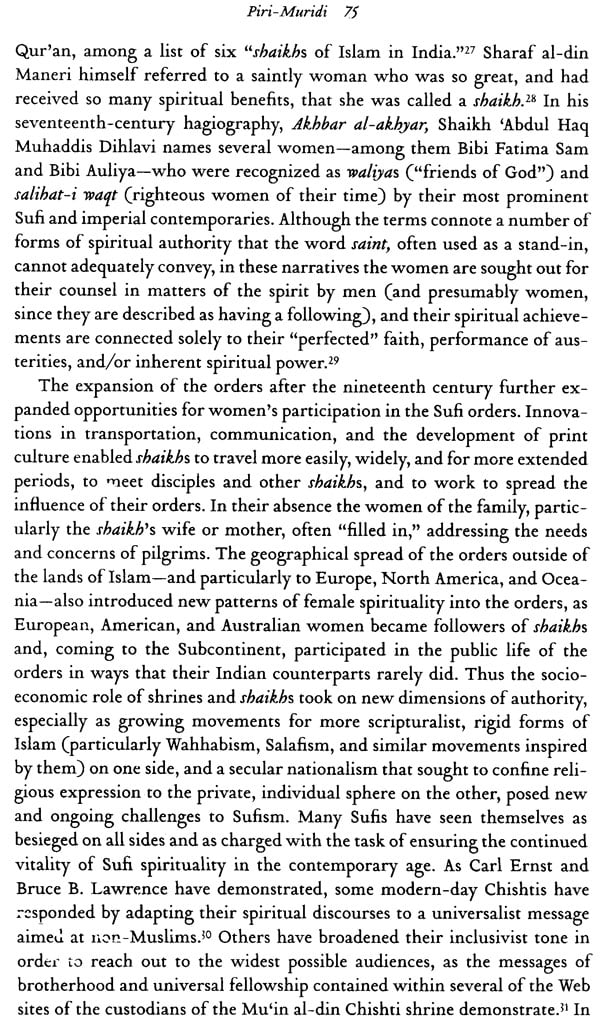

A number of ethnographic studies conducted since the late 1970S1 have suggested that there is a substantial gap between discourses about women's participation in ritual life and women's lived experiences in the world of Sufi shrines. While this issue has produced several promising studies of the role women play in contemporary Sufi praxis, the subject remains largely unexplored. Historical, theological, metaphysical, and philosophical studies of the question of gender in Sufism have yielded a rich tapestry of discussion about its ultimate ephemerality in the search for God. However, the question of living, 'flesh-and-blood women-particularly those considered saintly, possessed of divine attributes, or capable of mediating the power of a deceased Sufi sheikh (barak.at)-has helped to fuel stereotypes about the "dubious" nature of Sufism today. At the same time, the relationship between women and Sufi shrines is cited as evidence of Sufism's greater regard for women than "orthodox" or "scripturalist" Islam. Alternatively, and particularly among feminist scholars, women's activities in Sufi shrine settings are characterized as a manifestation of resistance to an Islamic patriarchy that is threatened by women's power, agency, or increasing pub- lice presence. None of these paradigms effectively answers the question of how women figure in contemporary Sufi praxis, nor can they address the question that is the central concern of this book, namely, how women can operate in the world of Sufi shrines as spiritual authorities and be recognized as such, even by those who otherwise condemn or criticize their activities.

Women as Participants: A Disconnect between Discourse and Praxis

While women frequently appear as pilgrims, clients, and disciples in writ- ten narratives about saints and shrines, much less is known, or reported, about those activities in which they are able to exercise a greater degree of agency and autonomy. As members of the family of a pir (pirzade), they are privy to information and knowledge about the shrine and its saints that the average pilgrim does not possess. As "ritual specialists" they may act on behalf of other women by petitioning the saint, and as healers and wise women, they may serve as the advisers and spiritual guides for male and female clients, although with few exceptions they are denied official recognition as pirs and sajada nisbins. They appear sometimes as storytellers and composers, and less frequently as performers at the qawwali musical assemblies held on major commemorative occasions. As the relatives of particularly prominent Sufi masters, they may be buried in shrine complexes, widely considered as saints, and venerated as such alongside their pious male relatives. A few have had shrines erected solely in their honor, as in the case of Bibi Kamalo, the maternal aunt of Shaikh Sharaf al-din Maneri, or Bibi Fatima Sam, whose tomb now lies in obscurity in the old Indraprastha section of Delhi but was at one time frequented by such notables as the fourteenth-century Chishti shaik.h Nizam al-din Auliya.

These facts were revealed only with patient prodding, and even then only after I had spent many months among the Sufi families who became the subjects of this study. I came to believe that their initial reluctance to discuss these aspects of women's experiences did not simply come from a religious or cultural sense of the impropriety of doing so, but rather that it was rooted in deeply entrenched, socially constructed and mediated attitudes about how women's participation (or lack thereof) in ritual life at Sufi shrines reflects prevalent ideals about Islamic womanhood. Thus an important agenda of this study was to go beyond a description of how women's participation in the world of Sufi shrines challenges and contests some of these ideals by investigating the ways in which participants also internalize and project dominant discourses in Islam about male-female relationships and the proper place of women within collective ritual spaces. This would require an integrated approach to the questions of language, action, and meaning as these are embedded within social experience but also shaped by a shared sense of culture, (meta) history, and faith.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages