Ancient Indian Asceticism

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDD870 |

| Author: | Dr. Mansukh Ghelabhai Bhagat |

| Publisher: | Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1976 |

| Pages: | 382 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.8" X 5.8" |

Book Description

About the Book:

"From the beginning of her history, India has adored and idealized not soldiers and statesmen, not men of science and leaders of industry, not even poets and philosophers but those rarer and chastened spirits .time has discredited heroes as easily as it has forgotten every one else but the saints remain," said the late Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, the eminent philosopher and our ex-President. Saints and ascetics have played an important role in moulding the religious history of India through the ages. The book attempts to examines how the holy men - seers and sages, rishis and munis, tapasvis and sannyasis, mystics and yogis - held a fasination to the Indian mind, as they do even now, as a symbol of holy life. In portraying their peculiar beliefs and practices and in investigating the genesis of their ascetic institution, the study takes a rapid survey of Brahmanical asceticism, Buddhist and Jaina monachism and their impact on the life and culture of ancient India.

When the ascetic movement first made its appearance, it was the greatest intellectual and religious force of the time. It captivated the noblest minds and produced the finest flowers of the human spirit, of whom many known and unknown seers of the Upanishads, the Buddha and Mahavira were representatives. For many centuries, thereafter, the highest spiritual life of the land found for itself, in its discipline, a sufficient and a satisfying expression. The work is a noble endeavour to capture some fascinating glimpses of that great movement and, in doing so, presents a vast panorama of ancient India - right from its earliest dawn, that of the Indus Valley civilization to the beginning of the Christian era.

About the Author:

Dr. M.G. Bhagat started his career, at 19, as a Havaldar Clerk of the Indian Army during the second world war, Late, in 1946, he joined an insurance company, when his real scholastic life began. Ambitions to achieve something worthwhile, he became an earner-learner, toiled for many years and received his Doctorate from the Bombay University in 1967. A product of our morning and evening colleges, he is a popular writer of the biographies of Saints and Sages of India, hundreds of journals. At present he edits the house journal of a premier Public Sector Organization.

In August 1957 in the Lok Sabha a Sadhu Bill urging the registra- tion of nearly six lakhs of Sadhus and Samnyasis was moved. The intention of the mover of the Bill was "to purge the increasing number of imposters and blacksheep robed in saintly saffron guise from committing unsocial acts." After an animated discussion the Bill was defeated as the Government found it difficult to implement it. The reasons were two-fold. Firstly, the law could not drag the nuns-Budhist, Jaina and Christian, who had renounced the world to line up with the Sadhus at a registration office. The very idea of registration was mundane to those who had left all social conven- tions. Secondly, the basic question was to define the terms Sachu' and 'Samnyasi' in the terms of law. It was found an impossible task; for once a samnyasi or monk took the vow of samnyasa or renunciation, he or she ceased to have any antecedents.

The discussion emphasised three salient points. Firstly, the Bill was an attack on the spiritual heritage of India. Secondly, this ancient institution had rendered yeoman services to the society by bringing about a healthy blending of material prosperity and spiritual requirement of the people. Thirdly, the ascetic in ancient India was known by many names. Rishis and munis, Yogis and mystics, Sages and samnyasis all alike basked under the holy ban- yan tree of asceticism.

The fake elements in the holy institution of Sadhus and Saran- yasis and their being involved in anti-social acts is not peculiar to modern times. The Kautilya Arthasastra, echoes the state of ascetic institution of those times and how it was viewed as a force which disrupted society. Even the Buddhist Vinaya Laws and Jaina Monastic jurisprudence partly reflect the anxiety of the Buddha and Mahavira to keep their orders pure in harmony with the social conscience. However, that is only the other side of the picture.

It is also true that no one can study India's ancient history and culture without being struck with the splendid heights and dignity of the aims of the ascetic movement and the seriousness of the men and women who were inspired by it. When the movement first made its appearance, it was the greatest intellectual and religious force of the time. It captured the noblest minds and ruled them. It produced the finest flowers of the human spirit of whom many known and unknown seers of the Upanishads, the Buddha and Mahavira were representatives. For many centuries, thereafter, the highest spiritual life of the land found for itself in its discipline, a sufficient and a satisfying expression. Only high ideals most earnestly pursued could have produced the lofty literature of asceticism and monastic ideals. The present thesis attempts to capture some glimpses of that move- ment, trace its genesis and evaluate its contributions to social, reli- gious, intellectual, ethical and other spheres of life of the people. It is a vast panorama of ancient India that the study seeks to capture -right from its earliest dawn to the beginning of the Christian era. The vastness of the subject and its deeper philosophical ramifica- tions permit us, however, to attempt only the main outlines of the problem.

The work is divided into eleven chapters. The sources utilised are Indian and foreign. In main literary sources of the Vedic texts, Buddhist and Jaina writings, the Epics (the Mahabharata, the Gita and the Ramayana), Arthasastra, Dharmasutras and Yogasutras are utilised for the purpose of investigation. The foreign sources consist of the impressions recorded by the Greeks and the Romans before and after the invasion of Alexander.

The method followed is two-fold. Firstly, the progressive develop- ment of asceticism is divided into various periods so as to enable us to have a full picture of each age and see how far the position of ascetic institution went on changing in response to the varying conditions and human needs of the society. Secondly, with a view to have a synthetic picture of the ascetic institution, a connected narrative of the different ideas and aspects of asceticism viz. Tapas, Vairagya, Samnyasa and Yoga is given while discussing the concept of asceticism. Each one of the four facets assume different forms of processes and disciplines of Indian asceticism at different times. Each aspect is separately treated with a view to show how each was closely related with the other to form a composit concept of asceti- cism. The evolution of ascetic institution as a socio-religious institu- tion can be perceived here clearly in its various strands and stages. With regard to the origin of asceticism, an attempt is made to study the problem from a perspective of human psychology besides that of stheology and philosophy of religion. It is also endeavoured to assess the impact of primitive religions on the ascetic beliefs and practices and the possible contributions of the pre-Aryans to the evolution of asceticism.

I am greatly beholden to all the scholars, Western and Eastern, whose works I have studied and utilised for the purpose of investig- ation. I am indebted to my guide Dr. L.B. Keny for the personal and persistent interest he has taken in the progress of my work at every stage. My thanks are also due to my innumerable friends, who have given me the benefit of their suggestions and advice from time to time.

This work, which has since been revised, was presented as a thesis to the Bombay University for which I was awarded the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

In the meanwhile, all constructive and valuable suggestions for the improvement of this work will be welcome.

It is the legacy of the European scholars, who in their attempt to understand and interpret Indian inheritance, have described the 'East as passive, tranquil and dreamy as opposed to the active, busy and practical West." India is symbolic of 'the brooding East' and it is very characteristic of her ancient wisdom that she has always appeared to them antique and mystic. It is due to this reason, it is often said that it is in the East that wisdom dawned earlier. This is also borne out by ancient India's speculative activity. When it was the beginning of philosophy in Greece, India had already made considerable progress in philosophy. And it has been rightly noted by a great scholar that the highest wisdom of Greece was 'to Know Ourselves'; the highest wisdom of India is 'to Know Our Self It is this wisdom and thought with their bewildering variety and mosaic pattern have drawn, not only in the past but even now to India's bosom, many a traveller in the quest of her rich and precious treasures. The journey might not have taken them to the goal of complete unfoldment of her ancient heritage, but the attempt must have been amply rewarding in the enrichment of the heart and mind of those who undertook this fascinating and eventful though arduous journey.

In the long line of such travellers was Max Muller who endea- voured to plumb the depths of the heart and mind of India. He took a lofty view of her art, sciences, literature and philosophy. Says he: 'Whatever sphere of the human mind you may select for your special study, whether it be language, or religion, or mythology or philosophy, whether it be laws or customs, primitive art or primitive sciences, everywhere you have to go to India, whether you like it or not, because some of the most valuable and most instructive materials in the history of man are treasured up in India and in India only. The word 'materials' means the sources viz. archaeology, sculpture, painting, literature and coins which unfold manifold aspects of India's cultural history.

Out of the many others, most worthy of mention are Goethe, Schopenhauer, Rolland and Toynbee. Goethe is said to have danced with joy over the German translation of the Sakuntala by Kalidas. Schopenhauer eloquently expressed his faith in the Upanishads: It has been the solace of my life; it will be the solace of my death.' Rolland, who interpreted Gandhi, Vivekananda and Ramakrishna Paramhamsa to the Western world said: 'If there is one place on the face of the earth where all the dreams of living men have found a home from the very earliest days when men began their dream of existence, it is India.' In very recent memory, Toynbee, as if to flatter us declared: 'In India there is an attitude towards life and an approach to the needs of the present situation in the world as a whole,' and exhorted her 'to go on giving the world Indian exam- ples of the spiritual fight that makes man human.

There is another type of travellers, who in their readiness to criticise, has only discovered the lower elements of Indian culture and thus failed to do justice to its higher aspects. In their endea- vour to analyse its essential strength and weakness, their vision and judgement fall an easy prey to hasty generalisations that accentuate only the weakness of Indian culture. Representatives of this class are a legion. p> Oman believes that 'It is the ascetic profession that time out of mind has been of pre-eminent dignity in the eyes of the Indian people.' Quite oblivious of the fact that they have also eminent regard for the heroic tradition, he adds: 'The only possible state of a religious (holy) life is one involving asceticism." Renou considers Hinduism as 'the very type of a religion of renunciation.' He labels this observation as 'a global characterization of Hinduism.

Schweitzer brands Indian religion, thought and culture as 'life- negating.'! McKenzie finds Indian asceticism 'full of abhorrent ideas, anti-social and not spiritual enough and as defended by philosophic thought does not partake of the nature of ethical acti- vity. Ronaldshay finds that 'Pessimism infects the whole physical and intellectual life of India and that the Indian philosophers have never been able to paint any positive picture of bliss. Koestler mocks at our Indian way of life, especially the Yoga tradition as a physical or spiritual discipline. To him Samadhi is 'pure imagination without thought." He feels that Indians are not as contemplative as they are reputed to be and concludes that he had 'never encountered a people as uncontemplative as the nation of Yogis.'! He is not merely a biased observer but a hostile witness. Many Western scho- lars unduly harp on the note of pessimism in Indian asceticism and characterize Indian thought as wholly pessimistic and other-worldly. To the research worker of history who has to discover and assess factual reality in its varied aspects from many divergent as well as harmonious views, both the sets of views are equally important and deserve careful examination.

It becomes necessary for the research worker, therefore, to be very careful in his interpretation of Indian culture. He has to view every cultural phenomenon or reality dispassionately, with a sense of historical proportion and perspective. Tradition is respected but not as a blind adoration of the past. The sentimental approach has to be discarded, inasmuch as tradition is examined in the context of its cultural setting to yield its essential strength as also its weak- ness. It is this approach that is intended to be followed to investi- gate the problem of asceticism in ancient India, its origin and development and its contribution to Indian culture as a whole.

fondly upheld and ascetic practices have been widely followed from very ancient times. Its roots seem to be lost in the mist of the pre-Aryan civilization. 'It is a tribute to the high metaphysical capacity of the Indian people;' says Deussen, 'that the phenomenon of asceticism made its appearance among them earlier and occupied a larger place than among any 0ther known people.'

Throughout the history of Hinduism, ascetic ideals have main- tained a stronghold on the minds of the people. To the mind of the Hindu, the life of the Sannyasi who has freed himself from all human ties and given up all physical comfort and well-being for a spiritual existence, has always seemed to be the highest. Even today its appeal to the masses as a symbol of holy life is consider- able. For ancient Indian culture is dominated by religion. And the assertion is not without truth that 'the Hindus are the most reli- gious people in the world, that is, the greatest slaves to the bondage of tradition."

The reason for the perpetuation of such a tradition can be traced to the role which the ascetic group of seers and rishis, saints and sannyasis, mystics and yogis played in moulding the religious history of India through the ages. The Vedas were revealed according to the orthodox tradition to rishis like Atri, Vasistha and Viswamitra and many others. Yajnavalkya, Sandilya, Manu, Valmiki and Veda Vyas, most of the thinkers of the Upanishads, Buddha and Maha- vira, belonged to the ancient family of seers, munis and ascetics. The six systems of philosophical thought, the Darsanas, are symbo- lic of India's moral and spiritual values. These were also origina- ted or promulgated by the rishis or ascetics." Ascetics and saints have played an important role in ancient India.' Even today holy men hold a real fascination for almost all the classes in India.

And a Western scholar has rightly observed: 'In Indiano religious teacher can expect a hearing unless he begins by renouncing the world. Dutt elaborates: 'One who has need to sway the group- mind whether a religious preacher, a social reformer or even a political leader-finds it to his purpose to appear in sannyasi's likeness in this country, for in that semblance he is able to com- mand the highest respect and the readiest following." This suggests how the Indian mind still perceives in him a symbolic relation to the moral and spiritual values the Bhiksu or the Sannyiisin embodi- ed in himself in ancient India.

| Abbreviations | ix | |

| Preface | xiii | |

| Chapter 1 | Introductory | 1 |

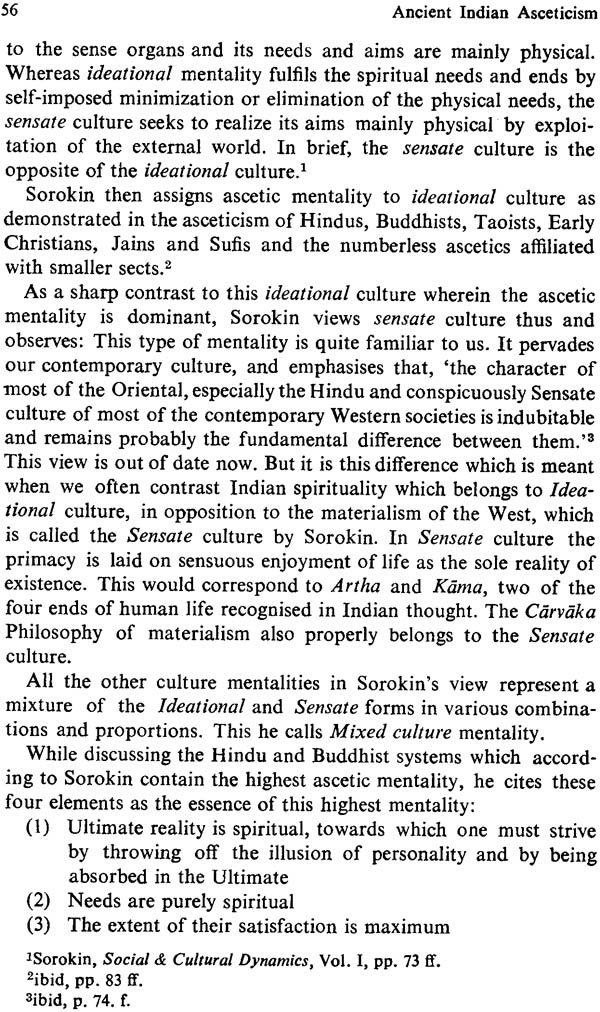

| Chapter 2 | The Concept of Asceticism | 9 |

| Chapter 3 | The Origin of Asceticism | 62 |

| Chapter 4 | Asceticism in the Indus Civilisation | 93 |

| Chapter 5 | Asceticism in the Early Vedic Literature | 100 |

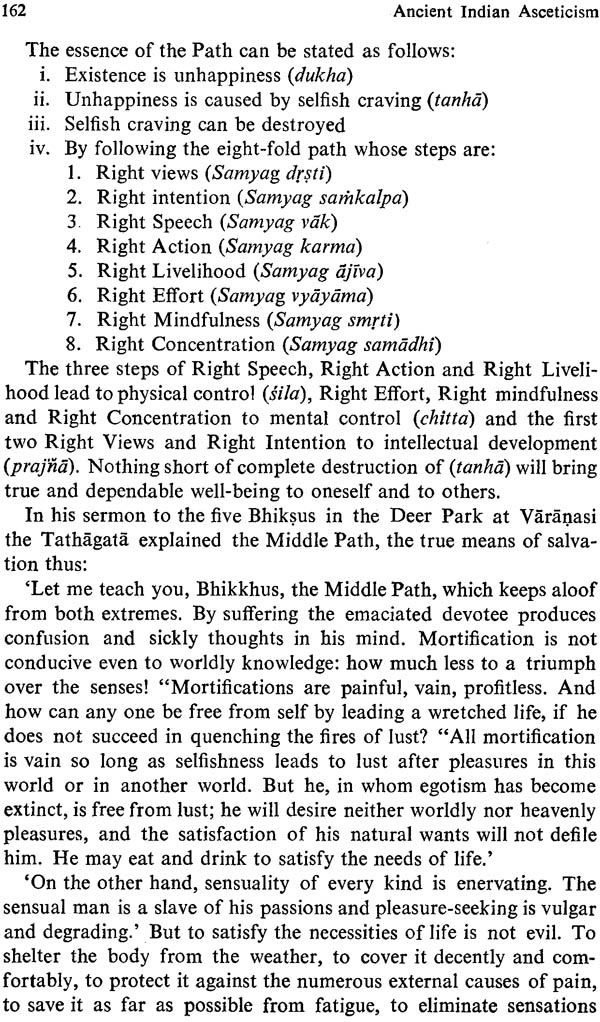

| Chapter 6 | Asceticism in Buddhist Literature | 138 |

| Chapter 7 | Asceticism in Jaina Literature | 169 |

| Chapter 8 | Asceticism in the Epics | 202 |

| i. The Mahabharata | 202 | |

| ii. Asceticism in the Bhagavad Gita | 233 | |

| iii. Asceticism in the Ramayana | 251 | |

| Chapter 9 | Asceticism in the Arthasastra | 281 |

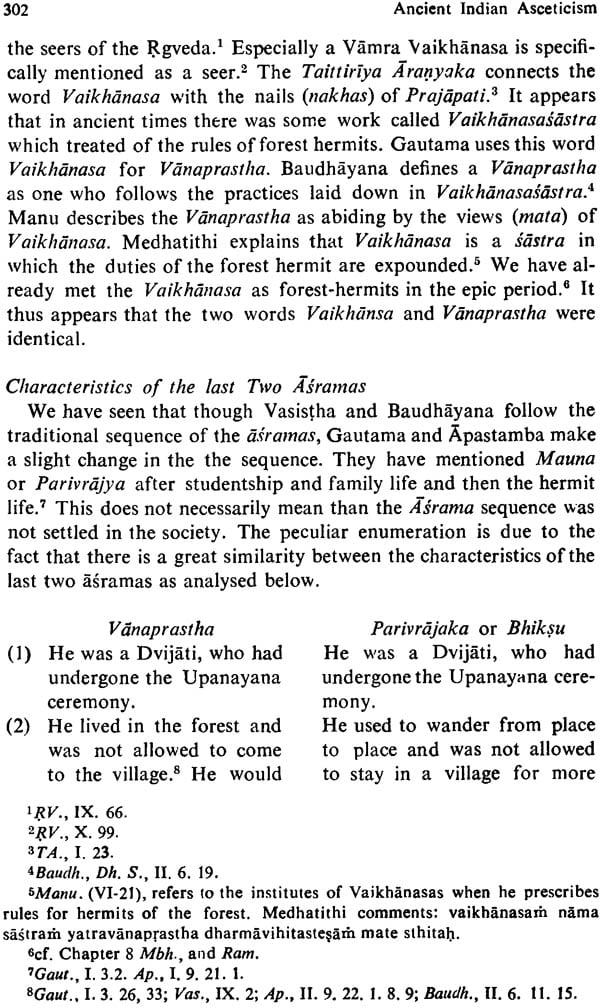

| Chapter 10 | Asceticism in the Law Books | 298 |

| Chapter 11 | Impact of Asceticism on Indian Civilisation | 312 |

| Bibliography | 335 | |

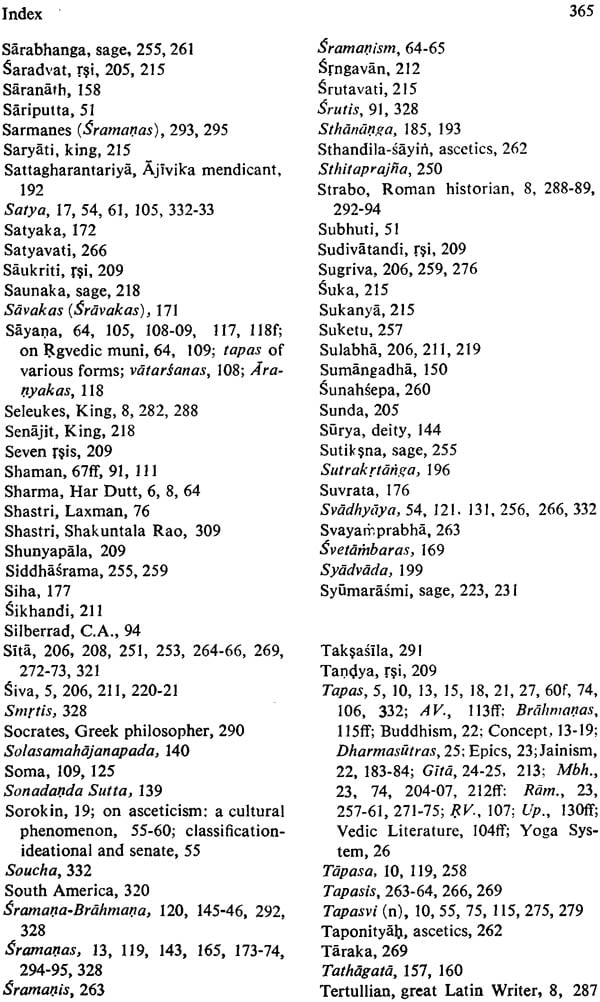

| Index | 357 |