Baroque India (The Neo-Roman Religious Architecture of South Asia: A Global Stylistic Survey)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDL074 |

| Author: | Jose Pereira |

| Publisher: | Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts and Aryan Books International |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2000 |

| ISBN: | 8173051615 |

| Pages: | 520 (Illustrated Throughout in B/W) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 10.9" X 8.8" |

| Weight | 2.19 kg |

Book Description

Baroque India is the fruit of cover 40 years of research, and is the work of one professionally trained in the history of Indian art (Hindu, Buddhist and Jain). In addition, he is the author of a survey of Islamic architecture world-wide, which includes, of course, the Indo-Islamic tradition. It is his belief that Indian Baroque-or, more correctly, India Neo-Roman-cannot be properly appreciated without an understanding of the architectural styles that preceded it on the subcontinent, and which exercised a significant impact on it.

To produce the book the author not only visited the various sites which contain the monuments of Indian Neo-Roman, but has travelled as an architectural pilgrim over much of the Neo-Roman world, in Europe and the Americas. He has also familiarized himself with the art-historical theories on the various styles of architecture, in particular, the Neo-Roman. He has thus prepared himself to contemplate Baroque India's contribution against the Neo-Roman background.

In consequence, the method adopted in this book has been that of summarily describing the distinctive spatial modalities of the various Neo-Roman styles, as reflected in their major monuments, especially the styles which impacted on India: a method that facilitates the discernment of the specific Indian contribution to Neo-Ramon taken as a whole.

In so doing, the author has tried to outline a consistent aesthetic theory of Neo-Roman, to portray its five major modes-Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassicism - as expressions of the Neo-Roman essence, immanently developing, in the indicated sequence, one from the other, and pullulating a rich variety of spatial themes that both display a marked originality and manifest a capacity for assimilating the spatial nuances of the other architectural styles. This theory, he believes, has enabled him to distinguish the originality of Indian him to distinguish the originality of Indian Neo-Roman, and describe what it has absorbed from the subcontinent's Indian and Indo-Islamic styles, while integrating the absorbed material into its Neo-Roman substance.

Jose Pereira is Professor of theology at Fordham University in New York, where he teachers History of Religions. He holds a doctorate from the University of Bombay in Ancient Indian History and Culture. He has been Visiting Professor at the Instituto Superior de Estudos Ultramarinos in Lisbon (1959-1960), research fellow in the History of Indian Art at the School of Oriental and Africa Studies in London (1962-1966), and Research Associate in the History of Indian Art at The American Academy of Benares at Varanasi (1967-1969). In the latter institution he chose as his project the architecture of Baroque India, and the present work is based on the research organized for that project. The photographs then taken in field trips to the various regions of Baroque India, including those reproduced in the present work, are preserved in the archives of the American Institute of Indian Studies at Varanasi.

Professor Pereira is the author of numerous articles and books - on theology, and on architectural, cultural, philological and literary history. Among his books are the following: Hindu Theology (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1976), Monolithic Jinas (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1979), Elements of Indian Architecture (Motilal Banarsidass, 1987), Islamic Sacred Architecture. A Stylistic History (New Delhi: Books & Books, 1994), and Baroque Goa. The Architecture of Portuguese India (New Delhi: Books & Books, 1995)

Cover Design: Teresa Pereira

The front of the cover displays the elevation of the church of Santana at Tallauli/Talaulim (1681-1695), possibly designed by FRANCISCO DO REGO. The back of the cover shows the interior of the church of Nossa Senhora da Divina Providencia in Velha Goa (1656-1661), designed by CARLO FERRARINI and FRANCESCO MERIA MILAZZO (photograph by Marie-Pierre Astier)

As is in other spheres of Indian life and art, the architecture heritage of India also exemplifies plurality and co-existence of many temporal moments and crossing of boundaries yet retaining an identity. Scores of monuments, shrines, and memorials distributed the country bear testimony to the twin processes of a distinct style as also osmosis which takes place with styles of earlier periods and adjacent areas as also assimilations of new influences. This event in India from very early times.

The several volumes on architecture published by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) bear testimony to the characteristic features of this dynamics of the interplay of the cosmic and the terrestrial, the humble indigenous and the monumental, the distinctively regional and the pan-Indian. A.K. Coomaraswamy's Essays in Early Indian Architecture throws light on the humbles hamlets as also the symbolic meaning of architectural members. Adam Hardy's book Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation takes the theme further by demonstrating convincingly the multilayered system. The study on Govindadeva: A Dialogue in Stone is a prefect example of the processes of interaction and fusion. The volume on Stupa and Its Technology: A Tibeto-Buddhist Perspective and Paul Mus's Barabudur: Sketch of a History of Buddhism Based on Archaeological Criticism of the Texts exemplify these processes in the context of Buddhism monuments found not only in India but also in Tibet and Indonesia. No architecture scheme appears to work in total isolation or insulation and yet it acquires a distinctive personality. Whether it is the potential of the Indian tradition to assimilate without being purely derivative or the more universal and complex processes of the giver and the receiver is difficult to priorities. It is evident that the trend continues well into the Eighteenth and even Nineteenth centuries. Prof. Jose Pereira's volume Baroque India: The Neo-Roman Religious Architecture of South Asia, A Global Stylistic Survey cogently traces the history of the evolution of Baroque in the context of India. His volume Baroque Goa: The Architecture of Portuguese India (Books and Books, Delhi, 1995) had focused on Goa. Prof, Pereira in the present monograph now explores thoroughly the applicability of terms like Baroque and Neo-Roman to a specific of colonial (local) architectural development in India represented by several grand edifices.

The colonial expansion in South Asia undoubtedly was an era of economic exploitation and political oppression. Nevertheless, it also brought in its wake the possibility of a dialogue between the East and West. There was mutual influence. Many seminal ideas travelled to the West and aspects of European knowledge and technology effected the Indian arts and crafts. In some cases hybrid styles emerged, in others there was a more meaningful blending of genres and styles. The history of this Indo-European dialogue is complex and a more balanced reassessment in different fields has yet to be made.

Without making evaluation statements, it is clear that there is evidence of the impact of the colonial presence in many domains of life and art. In architecture, buildings such as Tirumalan ayaka's Palace at Madurai; Mattancheri Palace, Cochin; several Nawabi mansions of Lucknow; and various notable edifices of Calcutta, Mumbai and elsewhere are typical examples.

The author in his monograph deals with the various issue relating to the transmission and growth of European architectural traditions in India within a local format. Giving the political history associated with the subject as a background, he discusses various other details, viz., the structural antecedents and stylistic aesthetics, architectural contents of the monuments connected with the Indian Baroque and Neo-Roman traditions and aspects of ornamentation and draws some significant conclusions.

Prof. Pereira gives us his overview of the political history, the aesthetics of the Neo-Roman, the characteristics of the Baroque, the interactions with Indian styles and the emergence of a distinctively Indian Baroque. Prof. Pereira builds up a strong case for Indianized Baroque as a regional development with characteristic, especially the churches including those raised by Protestants in the Western coastal areas, and elsewhere in India to stress his view-point. According to the author, the regional manifestation of the Goan Baroque also contains typical Indian elements associated with structural tradition of medieval India e.g. presence of amalakas, lotus and cypress motifs, pot-shaped pillar-bases, Bengal -roofs, etc., and develops its own structural features. HE also records the presence of certain features of Baroque style in some of the Hindu shrines of Goa built during the Portuguese rule. Prof. Pereira also tries to visualize some sort of aesthetic parallelism between Hindu temples and Baroque structures. Assessing the process of Indianization of Neo-Roman architecture, he describes it as "European in grammar and Indian in syntax, though later even grammar was considerably modified". Therefore, this type of stylistic transformation, as a whole, has to be treated as an Indian development in the same way as the Indo-Islamic architecture, which also was the result of a dialogue with architectural styles of non-Indian origin.

Prof. Pereira through an in-depth study of European and Indian architecture, methodical analyses and logical inferences has been able to expose almost an unknown chapter of Indian's art history. Our author, who besides being an architectural historian, is a linguist specialising in Latin and Sanskrit and other European and Indian languages, a specialist on religious and philosophical thought of Asia and Europe and a painter of repute. He has devoted more than two decades in carrying out the present study. In his conclusions, he attempts to highlight the contribution of India to Neo-Roman architecture idiomatically, axiomatically and aesthetically. I have no doubt that his exposition will interest both cultural historians as also students of architecture. Prof. Pereira's views and inferences on the subject may not be shared by some scholars or readers but his contribution to the colonial phase of Indian art is not without significance.

The IGNCA is deeply involved in the integrated study of Indian art and architecture under its Ksetra-Sampada programme in the context of which investigations are made on a structural heritage zone/area serving as a sacred centre, keeping in view its character in totality. The objective of these studies is to understand architecture as an expression of life in relation to rituals, myths, culture and environment. Goa as an architecture heritage zone with many notable shrines, sanctuaries and churches, bound together through a structural idiom, indeed serves as a point of cultural convergence and radiation bringing together the people to a common socio-religious fold. Prof. Pereira's present work corroborates IGNCA's approach to a Ksetra (area) and, is yet another example of the efficacy of IGNCA's theoretical position.

I am grateful to Prof. Pereira for allowing IGNCA to publish the book. I would like to thank my colleagues Mr. M.C. Joshi for reading the manuscript carefully, and Dr. Lalit M. Gujral for seeing it through the press.

| Foreword - By Kapila Vatsyayan | vii | |

| Prologue | ||

| 1. | Neo-Roman and the Baroque | 1 |

| 2. | Catholicism and the Baroque | 1 |

| 3. | Styles of Neo-Roman | 2 |

| 4. | World-wide diffusion of Neo-Roman | 3 |

| 5. | Neo-Roman in Asia and india | 3 |

| 6. | Synthetic and inclusive approach of the present work | 3 |

| 7. | Acknowledgements | 4 |

| 8. | Conventions used in the text | 5 |

| Chapter 1. Political History | 7 | |

| 9. | Creators of Baroque Indian History | 7 |

| 10. | The Indian dynasties | 12 |

| 11. | The three sacred imperialisms, Muslim, Christian and Hindu | 13 |

| 12. | Portuguese crusade against Islam | 14 |

| 13. | Hindu-Muslim wars in India | 16 |

| 14. | Portuguese India | 17 |

| 15. | Phases of Portuguese overseas expansion. Phase of the Indian empire | 17 |

| 16. | Phase of the Brazilian empire | 21 |

| 17. | Phase of the African empire | 23 |

| 18. | Dutch India | 27 |

| 19. | Phases of Dutch rule in India | 28 |

| 20. | Danish India | 28 |

| 21. | French India | 29 |

| 22. | Phases of French rule in India | 29 |

| 23. | British India | 31 |

| 24. | Phases of British rule in India | 31 |

| Chapter 2. Aesthetics of Neo-Roman | 36 | |

| 25. | Anthropic and cosmic character of architecture | 36 |

| 26. | Curved and rectilinear space: the Baroque and Classicism | 37 |

| 27. | Spatial characteristics of the Baroque, architecture of the curviform | 37 |

| 28. | Illuminational characteristics of the Baroque [65] | 38 |

| 29. | Classicism and the Baroque Impulse | 39 |

| 30. | Architectonic and Decorative Baroque | 39 |

| 31. | Mannerism | 40 |

| 32. | The Indian Aesthetic | 40 |

| 33. | Scientific and intuitive awareness of the structure of the cosmos | 44 |

| 34. | Trabeate and arcuate construction | 45 |

| 35. | The Parthian and Roman General of arcuate architecture | 45 |

| 36. | India and the Parthian and Roman Genera | 47 |

| 37. | The Neo-Roman styles in India | 48 |

| 38. | Inauguration of the Neo-Roman Revolution | 48 |

| 39. | BRUNELLESCHI'S four-point programme: the Four Specifics of Neo-Roman architecture | 49 |

| 40. | Classical precedent for BRUNELLESCHI's programme | 50 |

| 41. | Roman attitudes to the programmatic organization of space | 50 |

| 42. | Decay of the programmatic approach | 51 |

| 43. | Restoration of the programmatic approach in medieval Italy | 51 |

| 44. | Transformation of the Four Specifics. Transformation of Specific 1, idiom | 52 |

| 45. | Transformation of Specific 2, proportion | 57 |

| 46. | Transformation of Specific 3, syntacticity | 59 |

| 47. | Transformation of Specific 4, perspective | 60 |

| 48. | Ambiguity of Neo-Roman | 61 |

| 49. | Assimilative power of Neo-Roman | 62 |

| 50. | Aesthetics of fragmentation and integration in Neo-roman | 62 |

| 51. | The nine categories: criteria for the definition of the Neo-Roman style | 64 |

| 52. | Definition of styles, 1. Renaissance | 65 |

| 53. | Renaissance idiomatics: the classical orders | 67 |

| 54. | Description of the five orders [4,5]. | 68 |

| 55. | Renaissance decorative forms | 70 |

| 56. | Definition of style, 2. Mannerism | 71 |

| 57. | Academic Mannerism | 71 |

| 58. | Antinomian Mannerism | 75 |

| 59. | Microtectonic Antinomian Mannerism | 76 |

| 60. | Macrotectonic Antinomian Mannerism | 77 |

| 61. | Mannerist decorative Forms, architectonic, Antinomian | 79 |

| 62. | Mannerist decorative forms, picturesque | 80 |

| 63. | Definition of styles, 3. Baroque | 81 |

| 64. | Baroque spatially | 81 |

| 65. | Baroque illumination [28] | 83 |

| 66. | Baroque decorative forms | 86 |

| 67. | The salomonic column | 87 |

| 68. | Renaissance revival of the salomonic column | 87 |

| 69 | Morphology of the salomonic column | 88 |

| 70. | Spiral shaft of the salomonic column | 88 |

| 71. | Unscrolled zone of the salomonic column | 89 |

| 72. | Scrolled zone of the salomonic column | 89 |

| 73. | Living creatures figured on the salomonic column | 90 |

| 74. | Acanthus ring on the salomonic column | 91 |

| 75. | Definition of styles, 4. Rococo | 91 |

| 76. | Rococo decorative forms | 93 |

| 77. | Definition of styles, 5.Neoclassicism | 95 |

| Chapter 3. Architecture: Evolution, Styles, History And Historiography | 103 | |

| 78. | Three main European sources of Indian Neo-Roman | 104 |

| 79 | Prelude to Portuguese Neo-Roman: the Manueline (1480-1560) | 105 |

| 80. | Vestiges of the Manueline India | 107 |

| 81. | Portuguese Renaissance (1490-1550) | 111 |

| 82. | Mannerism in Portugal and Brazil | 112 |

| 83. | Portuguese and Brazilian Baroque (1680-1780) | 115 |

| 84. | Portuguese and Brazilian Rococo (1750-1800) | 120 |

| 85. | Portuguese and Brazilian Neoclassicism (1760-1850) | 123 |

| 86. | Neo-Roman in France. French Renaissance (1490-1540) | 123 |

| 87. | French Mannerism, Academic and Baroquized (1540-1780) | 123 |

| 88. | Rococo Interlude (1730-1760) | 125 |

| 89. | French Neoclassicism (1760-1840) | 126 |

| 90. | Neo-Roman in French India | 127 |

| 91. | Neo-Roman in Britain | 129 |

| 92. | British Baroquized Academic Mannerism and Antinomian Mannerism | 130 |

| 93. | British Neopalladianism | 131 |

| 94. | Regions of Neo-Roman architecture in India | 133 |

| 95. | Styles of Neo-Roman architecture in India | 134 |

| 96. | General characteristics of the Indian Neo-Roman styles | 135 |

| 97. | General characteristics of the West Coast styles | 136 |

| 98. | General characteristics of the Malabari style | 137 |

| 99. | Characteristics of the Norteiro style | 140 |

| 100. | Characteristics of the Konkani style | 141 |

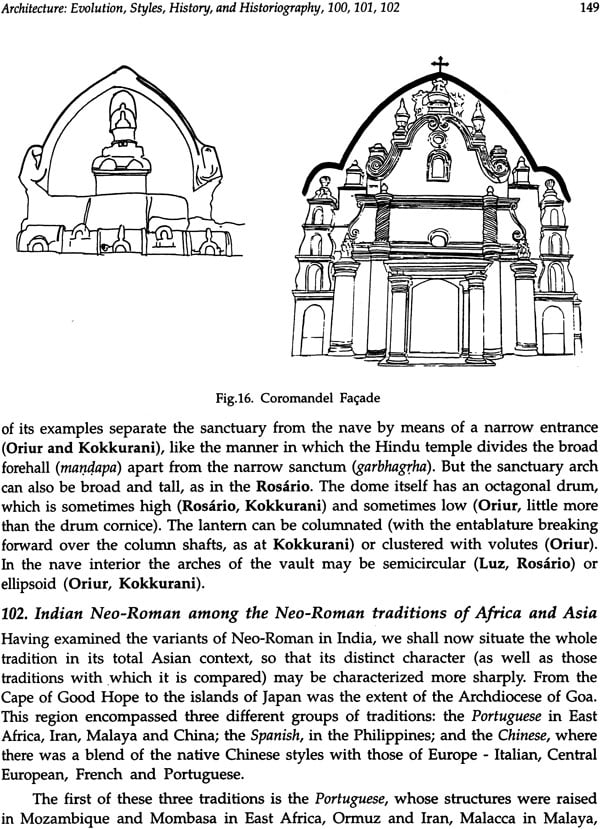

| 101. | Coromandel style | 148 |

| 102. | Indian Neo-Roman among the Neo-Roman traditions of Africa and Asia | 149 |

| 103. | Neo-Roman in China | 151 |

| 104. | Filipino Neo-Roman | 152 |

| 105. | Periods of Indian Neo-Roman history | 156 |

| 106. | First periods: implantation of the European style (1500-1550) | 156 |

| 107. | Second periods: genesis of the Indian style and the maturity of the European (1550-1760) | 157 |

| 108. | Third period: maturity of the Indian style (1660-1760) | 161 |

| 109 | Fourth periods: Finals of the Indian and European styles (1760-1850) | 162 |

| 110. | Historiography of Neo-Roman architrcture20 | 163 |

| 111. | Historiography of Indian architecture | 164 |

| 112. | Historiography of Portuguese architecture | 165 |

| 113. | Initiation of Indian Neo-Roman art historiography | 168 |

| 114. | Contemporary Portuguese art historiography | 170 |

| 115. | Contemporary art historiography of Neo-Roman India | 172 |

| Chapter 4. Catholic Churches: Types | 177 | |

| 116. | The Christian church | 178 |

| 117. | Types of Christian church, central and longitudinal | 179 |

| 118. | Types of Neo-Roman churches in India | 182 |

| 119. | The Hall church | 183 |

| 120. | Goan Hall churches | 185 |

| 121. | The Se (catedral de Santa Catarina) in Velha Goa. Neo-Roman cathedrals in the Iberian world | 186 |

| 122. | The architect of the Se, JULIO SIMAO/JULES SIMON (fl. 1565-1641) | 187 |

| 123. | Brief history of the Se | 190 |

| 124. | Herreran idiom of the Se | 191 |

| 125. | Other similarities and some differences between the Simonian and Herreran idioms | 191 |

| 126. | Interior spatiality of the Hall Church, in particular, the Se | 192 |

| 127. | Latin cross-domed church | 195 |

| 128. | Interior spatiality of the Latin cross-domed church | 197 |

| 129. | Interior spatiality of the Franco-Indian Latin cross-domed churches | 198 |

| 130. | Greek cross-domed church | 200 |

| 131. | Evolution of the Greek cross-domed church | 201 |

| 132. | Interior spatiality of the Greek cross-domed church | 203 |

| 133. | Exterior spatiality of the Neo-Roman church. Some types of façade | 204 |

| 134. | Towers façades | 205 |

| 135. | Wall façades | 206 |

| 136. | Types of Wall façade, 1. The hollowed façade | 207 |

| 138. | Types of Wall façade, 3. The templiform façade | 211 |

| 139. | Column façade | 210 |

| 140. | Indian Neo-Roman façade. The Tower façade | 212 |

| 141. | Goan Immured Prostyle façade, the Providencia | 212 |

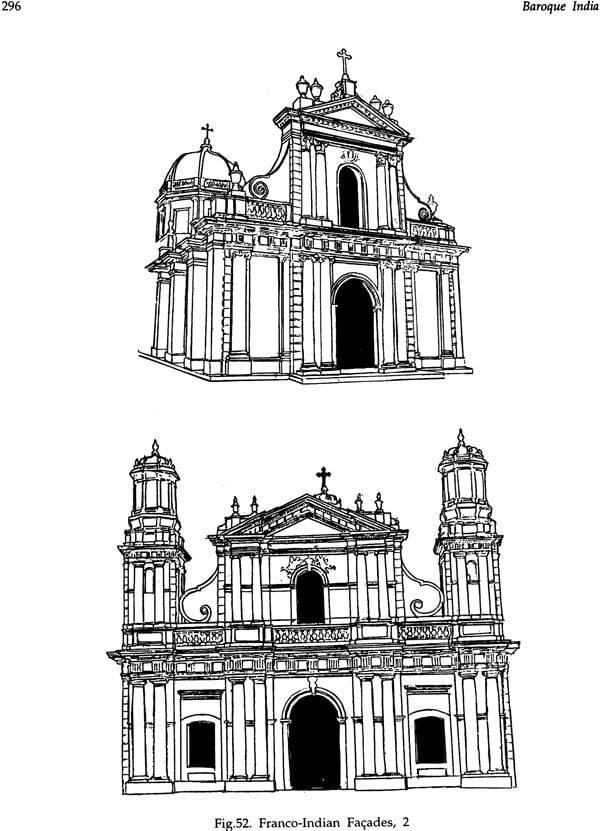

| 142. | Franco-Indian Immured Prostyle facade | 217 |

| 143. | Indian versions of the Standard Italian façade | 217 |

| 144. | Franco-Indian façade of Standard Italian format | 220 |

| 145. | Neo-Roman dome | 223 |

| 146. | Varieties of the Neo-Roman dome | 225 |

| 147. | Indian Neo-Roman domes | 227 |

| Chapter 5. The Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 233 | |

| 148. | Notes of the Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 233 |

| 149 | Other features of the Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 235 |

| 150. | Various formats of the Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 235 |

| 151. | The standard or oblong format of the Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 236 |

| 152. | The polygonal format of the Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 238 |

| 153. | The curviform format of the Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 239 |

| 154. | The mixtilinear format of the Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 239 |

| 155. | The Box Church and its evolution | 239 |

| 156. | The Indian Diminuted Sanctuary Church | 240 |

| 157. | Portals | 241 |

| 158. | Porch and narthex façades | 244 |

| 159. | Fronton shapes | 245 |

| 160. | Volute shapes | 249 |

| 161. | Finials | 251 |

| 162. | Façade and rear towers | 252 |

| 163. | Compartmentation or reticulation | 253 |

| 164. | Column-pilaster combinations | 258 |

| 165. | Contrast in days and storeys | 260 |

| 166. | Arrangement of voids | 262 |

| 167. | Unpierced surfaces | 264 |

| 168. | Emblems and niches | 265 |

| 169. | Frontispiece-tower interlink | 266 |

| 170. | Interiors: structural units | 267 |

| 171. | The Goan planed groin vault | 270 |

| 172. | Organization of the interior | 274 |

| Chapter 6. Gilt-Woodwork: Retables And Pulpits | 297 | |

| 173. | The Christian altar | 298 |

| 174. | Functions of the altar | 298 |

| 175. | Traditions of the altar | 299 |

| 176. | The Portuguese altar traditions | 300 |

| 177. | The Indian altar traditions | 303 |

| 178. | The idiomatics of the altar: basic features | 306 |

| 179. | Idiomatics of the altar: architectural articulation | 307 |

| 180. | Axiomorphics of the altar: altar types | 307 |

| 181. | Axiomorphics of the altar: altar types | 309 |

| 182. | Axiomorphics of the altar: special environment | 309 |

| 183. | Iconography of the altar | 310 |

| 184. | Portuguese and Brazilian iconography | 313 |

| 185. | Indian iconography | 314 |

| 186. | Aesthetics of the altar | 316 |

| 187. | Evolution of the retable | 318 |

| 188. | Shrine Retable | 319 |

| 189. | Tabernacle: theology | 320 |

| 190 | Tabernacle: types | 321 |

| 191. | Expositorium | 322 |

| 192. | Portuguese Expositorium or trono | 325 |

| 193. | Indian tabernacles | 329 |

| 194. | Parietal Retable | 330 |

| 195. | Main features of the retable, 1: plan | 330 |

| 196. | Main features of the retable, 2: spacing of the bays | 330 |

| 197. | Main features of the retable, 3: voids | 332 |

| 198. | Main features of the retable, 4: predella or socle | 334 |

| 199. | Main features of the retable, 5: attic | 335 |

| 200. | Portuguese Pinnacled and Aedicular Attics | 336 |

| 201. | Portuguese Arched Attics | 338 |

| 202. | Portuguese Convoluted Attics | 339 |

| 203. | Indian attic | 342 |

| 204. | Indian Aedicule Attics, first phase | 344 |

| 205. | Indian Aedicule Attics, Second phase | 347 |

| 206. | Indian Convoluted Attics | 349 |

| 207. | Indian Arched Attics | 350 |

| 208. | Main features of the retable, 6: enframement | 352 |

| 209. | Pulpit: Theology | 354 |

| 210. | Description of the pulpit | 355 |

| 211. | Indian pulpits | 355 |

| 212 | Indian salomonic columns | 355 |

| 213. | Five Indian pulpit traditions | 356 |

| 214. | Evolution of the ornamentation of the Indian pulpit | 358 |

| 215. | Components of the Indian pulpit | 358 |

| 216. | Evolution of the component of the Indian pulpit | 358 |

| 217. | Subdivision of the components of the Indian pulpit | 359 |

| 218. | Parts of the Indian canopy | 359 |

| 219. | Indian pulpit cupola | 359 |

| 220. | Indian pulpit crown | 360 |

| 221. | Indian coronal volutes and cresting motifs | 360 |

| 222. | Indian pulpit tester | 360 |

| 223. | Indian pulpit supraport | 361 |

| 224. | Indian pulpit doorway | 361 |

| 225. | Indian pulpit encincture | 363 |

| 226. | Indian pulpit bowl | 365 |

| 227. | Indian pulpit stalk | 365 |

| Chapter 7. Crosses, Shrines And Hindu Temples | 369 | |

| 228. | Connection between piazza crosses, wayside shrines, and Hindu temples | 369 |

| 229. | Indo-Syrian piazza cross | 369 |

| 230 | Indo-Latin piazza cross | 371 |

| 231. | Wayside shrines or furis | 376 |

| 232. | The Hindu temple [cf. 32] | 376 |

| 233 | The Maratha temple | 380 |

| 234 | The Goan temple | 381 |

| 235. | Associate structures of the Goan temple | 386 |

| 236. | Goan church and Hindu temple compared | 387 |

| 237. | Evolution of the Goan Hindu temple | 388 |

| 238. | fate of the Goan Hindu temple | 389 |

| Chapter 8. Protestant Churches | 397 | |

| 239. | Protestant architecture church | 397 |

| 240. | Paradoxes of the Protestant church | 398 |

| 241. | Creation of a distinctive Protestant architectural history | 398 |

| 242 | Protestantism and the Baroque | 399 |

| 243. | Dutch Classicism | 399 |

| 244. | Four periods of Protestant architectural history | 400 |

| 245. | Initial; period (1540-1600), of Protestantization | 400 |

| 246. | Centralized oblong plan | 401 |

| 247. | Galleried interiors | 401 |

| 248. | Second period (1600-1650), of Dutch dominance or Protestant autonomy | 402 |

| 249. | Dutch Protestant architecture of the second period | 402 |

| 250. | Danish Protestant architecture of the second period | 403 |

| 251. | French Protestant architecture of the second period | 403 |

| 252. | British Protestant architecture of the second period | 403 |

| 253. | Third period (1650-1750), of British and German dominance , or Catholicization | 404 |

| 254. | British Protestant churches of the third period. The evolution of the Anglican church | 404 |

| 255. | Eccentric varieties of the Anglican church | 406 |

| 256. | Standardization of the Anglican church | 406 |

| 257. | Problem of a distinctive exterior silhouette for a Protestant church | 407 |

| 258. | Evolution of the paradigm of the Anglican church | 407 |

| 259. | Limitations of the paradigm | 408 |

| 260. | British Indian Protestant churches of the third period | 409 |

| 261. | Danish protestant churches of the third period | 409 |

| 262. | Danish Indian Protestant churches of the third period | 410 |

| 263. | Fourth period (1750-1900), of America dominance or-Protestantization | 410 |

| 264. | British Protestant architecture of the fourth period | 410 |

| 265. | British Indian Protestant architecture of the fourth period | 411 |

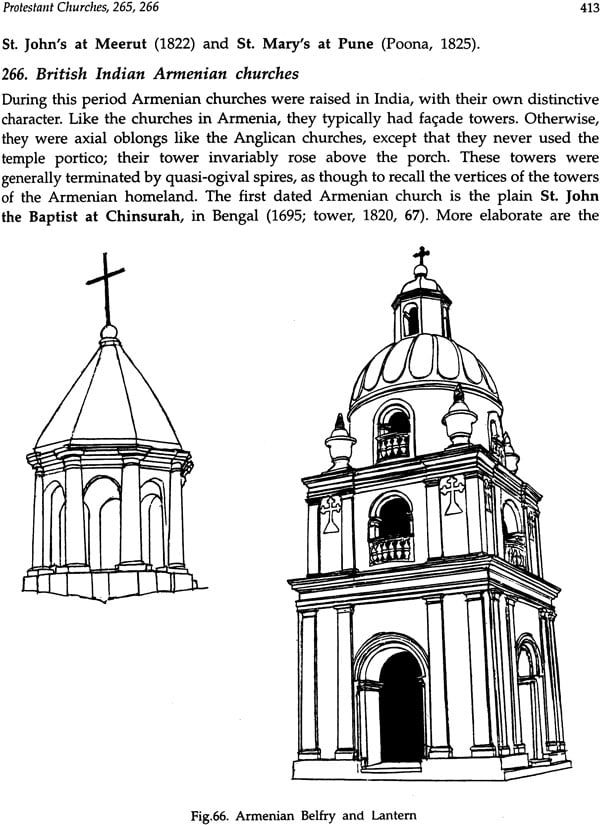

| 266. | British Indian Armenian churches | 413 |

| Epilogue | 417 | |

| 267. | Historical importance of Indian Neo-Roman | 417 |

| 268. | Idiomatic contribution of India to Neo-Roman architecture | 418 |

| 269. | Axiomorphic contribution of Indian to Neo-Roman architecture | 419 |

| 270. | Aesthetic contribution of India to Neo-Roman architecture | 420 |

| List of Illustrations | 423 | |

| 271. | Line drawings | 423 |

| 272. | Plates. Interspersed in text. Plates 1-12 | 432 |

| 273. | Plates: Portfolio, 1. Piazza crosses. Plates 13-16 | 433 |

| 274. | Plates: Portfolio, 2.Façades. Plates 17-35 | 433 |

| 275. | Plates: Portfolio, 3. Interiors. Plates 36-50 | 435 |

| 276. | Plates: Portfolio, 4. Vaults and domes. Plates 51-65 | 436 |

| 277. | Plates: Portfolio, 5. Retables and tabernacles. Plates 66-89 | 437 |

| 278. | Plates: Portfolio, 6. Pulpit. Plates 90-97 | 440 |

| 279. | Plates: Portfolio, 7. Indian Gothic. Plates 98-99 | 440 |

| 280. | Plates: Portfolio, 8. Ecclesiastical furniture and woodwork. Plates 100-104 | 441 |

| Bibliography | 443 | |

| 281. | Bibliography of Indian Neo-Roman. From 1951 | 443 |

| 282. | Tribute to Significant art historians | 445 |

| Index | 447 | |

| 283. | Persons | 447 |

| 284 | Monuments | 455 |

| 285. | Themes | 480 |