Buddhist Art in India, Ceylon and Java

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDC860 |

| Author: | J. Ph. Vogel |

| Publisher: | Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2017 |

| ISBN: | 9788121513135 |

| Pages: | 167 (45 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch X 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 340 gm |

Book Description

J. Ph. Vogel's Buddhist Art in India, Ceylon and Java is an English translation of the original De Buddhistische Kunst Van Voor-Indiee, enlarged in scope and including also an account of the Buddhist art of Ceylon and Java.

The present book has been written with the chief object to give a historical outline of Indo-Buddhist art, to sketch its various schools in their main characteristics and to trace their mutual relationship. Attempt has also been made to show by Vogel in what manner the artistic phenomena must have followed the religious developments and spiritual movements.

Apart from an Introduction giving a brief background, the entire period of nearly fifteen hundred years of Buddhist art from the third century BC to the twelfth century AD has been covered in seven chapters and two chapters on the Buddhist art of Ceylon and Java respectively.

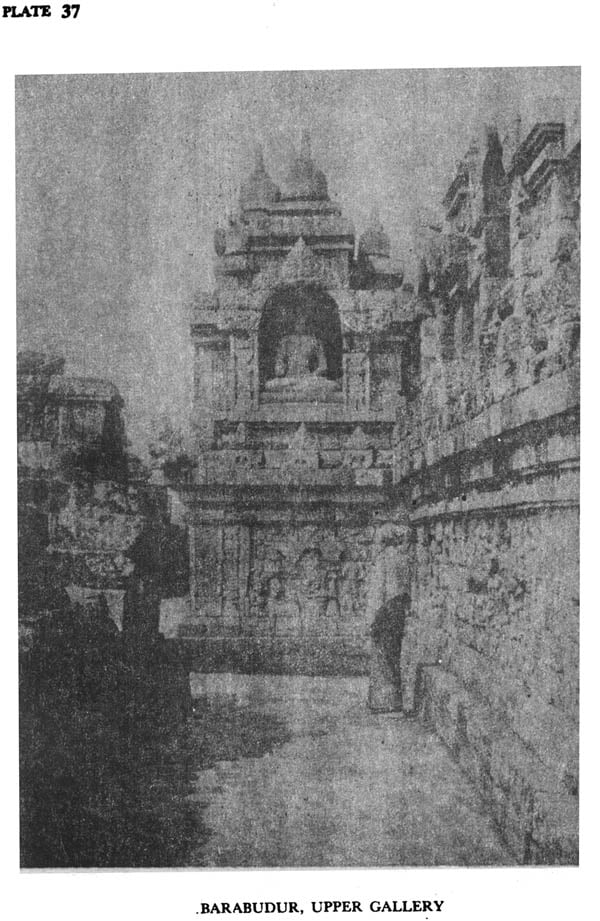

Coming as it does from the pen of J. Ph. Vogel, the Buddhist Art in India, Ceylon and Java commends itself as a most useful handbook on the subject. The book contains a very representative selection of photographs on the subject included in thirty-nine plates apart from a ground-plan of Borobodur, the great monument of the Mahayana, with its harmonious blending of Indian and local elements and wonderful display of sculptural decoration. The book also contains an index and bibliography giving titles of principal works of reference.

Jean Philippe VogeI1871-1958, popularly known by his initials J. Ph. Vogel, was a Dutch Sanskritist and epigraphist. Vogel worked as Superintendent of the Punjab, Baluchistan and Ajmer based at Lahore from January 1901 to 1914. Between 1910 and 1911, he even deputised as Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India in the absence of John Marshal. As an archaeologist, Vogel participated in the excavations at Gandhara, the Punjab Hill States, Kusinagara and Mathura.

In February 1935 the Secretary to the Delegates of the Clarendon Press addressed me regarding the possibility of bringing out an English translation of my book De Buddhistische Kunst van Voor-Indie, published in 1932 by Messrs. H. J. Paris, Amsterdam. He suggested at the same time that the proposed English version should include an account of the Buddhist Art of Ceylon and Java, and it was considered desirable to give special prominence to that most important monument of the Buddhist religion-the Barabudur of Java.

There was all the more reason to accept the proposal of the Clarendon Press because Dr. A. j. Barnouw, Professor of the History, Language, and Literature of the Netherlands in Columbia University, had declared his willingness to undertake the translation. Let me take this opportunity to express my indebtedness to Professor Barnouw for the care bestowed by him on this task. The readiness with which 'Mr. H. J. Paris has lent his co-operation is also greatly appreciated. The inclusion of Ceylon and Java in a book dealing with the Buddhist Art of India has much to commend it. In both these islands ancient architecture and sculpture, though obviously derived from the Indian Continent, show an independent development in which the workings of indigenous sources of inspiration are unmistakable. The harmonious blending of Indian and local elements has produced in both cases a truly national art which, in my opinion, it is misleading to designate, as is sometimes done, by the slightly depreciative term' colonial' . It may in truth be said that ancient Java especially has yielded works of art which are unsurpassed by anything found in the Indian homeland. In the Barabudur with its wonderful display of sculptural decoration the Indian stupa attains its highest perfection. My brief account of this marvellous monument of the Mahayana is largely dependent on Professor N.J. Krom and Lieut.- Colonel Th. van Erp's volumes in which a century of archaeological research has been embodied.

In dealing with the ancient monuments of Ceylon the want of an up-to-date handbook is painfully felt. Here, too, archaeological research has made considerable progress during the last twenty years, so that earlier publications like Henry Cave's beautifully illustrated volume have now become antiquated. In my chapter on the Buddhist Art of Ceylon it has been my endeavour to include, as much as possible, the results of recent investigations. I wish here to record my great obligation to Mr. A. M. Hocart, late Archaeological Commissioner of Ceylon, and to Mr. S. Paranavitana, the learned editor of the Epigraphia Zeylanica, who have favoured me with many valuable suggestions.

It is, in truth, a somewhat bold undertaking to present an account of the architectural and sculptural art of Ceylon and Java in two brief chapters. But it must appear even more presumptuous to handle the Buddhist Art of all India in a book of so limited a size. That art covers a period of fifteen centuries and in the course of that vast expanse of time has revealed itself in many local schools, Showing remarkably divergent varieties of style. With regard to this manifestation of Oriental Art it would certainly be most inappropriate to speak of the unchangeable East'.

In the present handbook it has been my chief object to give a historical outline of Indo- Buddhist Art, to sketch its various successive schools in their main characteristics, and to trace their mutual relationship. Some slight attempt has also been made to show in what manner the artistic phenomena must have followed the religious developments and spiritual movements of which they are the tangible signs.

I have preferred to keep to the firm ground of historical treatment rather than to be allured into the quicksands of aesthetic disquisition, which is too often biased by personal prejudice. At the same time I am ready to admit that in historical 'problems relating to Indo- Buddhist Art more uncertainty prevails than will perhaps appear from these pages. The modest size of my book did not admit of any extensive discussion of debated questions.

Buddhism has been extinct in India" the land of its birth, for nearly seven hundred years. One has to go down to Burma to find it still a vital force in the religious life of the people. But the visitor who knows Buddhist teaching through the study of the sacred writings will wonder at the spectacle of these happy Burmese folk as they go up, in festive garb, to the pagodas aglow with blazing colours. Is this cheerful religion, he will ask in surprise," the melancholy Buddhism of the ancient Pali books?

It is with equal wonder that we ask ourselves what connexion there can be between the doctrine of Buddha and the Buddhist art of India. That ancient lore weighs us down with its pessimism, it chills us with its despair of life and renunciation of the world, for it teaches man's highest aim to be release from the great sorrow which is inseparable from ali existence. Such a doctrine of escape seems a barren soil for an art such as we find in India, an art which revels in luxuriant forms and profusion of colours.

It is a case of nature refusing to be regulated. The temper of the Indian people has asserted itself like sunshine breaking through the clouds. The Indian, in his inmost being, feels a powerful impulse to worship the deity and to manifest that worship in visible signs and tangible symbols.

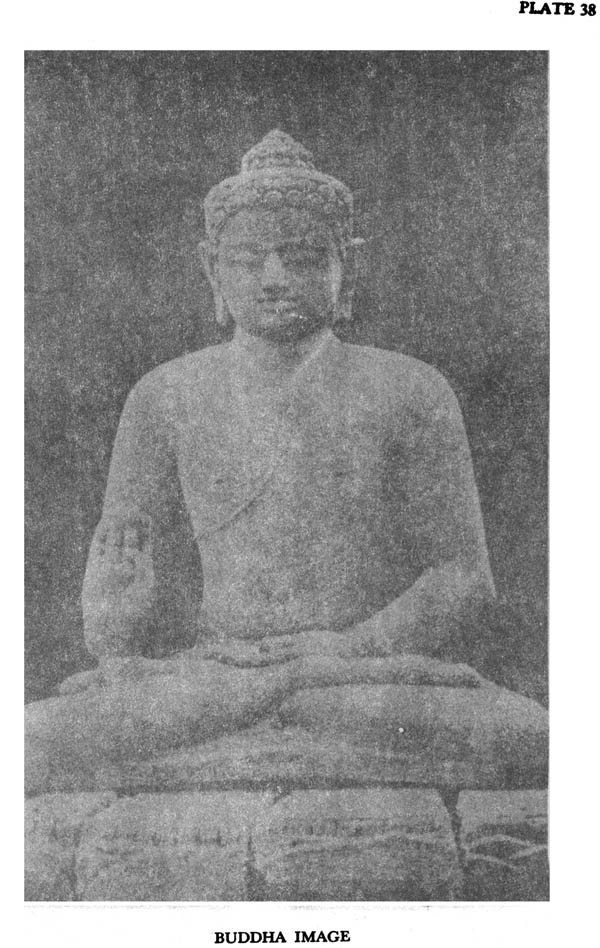

In Buddhist India it was the person of the great Master himself which satisfied that impulse to worship. The homage of his followers raised him upon the throne of the deity, which he himself had left empty. He was at first worshipped in his relics, later on also in his image.

That deep-rooted need to adore is coupled in the Indian with yet another craving, a veritable passion for adornment, the evidences of which can still be observed in present-day India. The Hindu covers not only the white walls of his house with various colourful figures, he decks even animals, such as elephants and horses, with paints, if only their natural hue fends itself as a background for gaily tinted ornament. This pleasure in decoration, which sometimes deteriorates into a mania, also manifests itself, with ever-increasing insistence, in old Indian literature. It is, indeed, one of the most- characteristic features of the plastic art of the Indians.

Those who know Buddhist art solely from the ruins, the mouldering images, the faded frescoes of India proper, can scarcely visualize the gay splendour which those ancient sanctuaries must once have radiated. Such an orgy of colours would dumb- found a Westerner. The surface of these crumbling buildings was once covered with a layer of gleaming white plaster, which was doubtless not left unadorned.

One can still find traces of colour and gilding on the sculptures of stone and stucco. Those mutilated grey stone images of Buddha must have stood there once with orange robe and gilded skin, as the faithful imagined that the Master himself had walked the earth. But one has to go to Burma, or to Ceylon, where Buddhism is still a living religion, in order fully to realize the gorgeousness of that Oriental splendour.

Though it is difficult to discover any connexion between the doctrine of Buddha and the plastic art of the Buddhists, it does not follow that this art never expresses the serene peace of mind, the infinite compassion and tenderness, and similar sublime qualities that mark the moral teaching of the Master. But the profound philosophical foundations upon which the Buddhist world religion has been built can be left out of account when the object of our study is the wealth of sculpture and fresco that has been lavished upon the adornment of that noble edifice.

We must, however, give a moment's thought to the Buddha himself, the first person of that holy Trinity-the Buddha, the Dharma (his Doctrine), and the Sangha (his Congregation) to whom every faithful Buddhist turns for protection. For the life of the Buddha was to the artists of ancient India an inexhaustible source of inspiration when they were, called upon to decorate the sacred shrines.

Contents

| List of Plates | XI | |

| I | Introduction | 1 |

| II | The Mounments of Asoka and the national School of Sculpture of Central India | 10 |

| III | The Graeco-Buddhist Art of Gandhara | 18 |

| IV | The Sculpture of Mathura Under the Kushana Dynasty | 28 |

| V | The South-Indian Art of Amaravati | 38 |

| VI | The Golden Age During The Gupta Dynasty | 49 |

| VII | The Buddhist Cave Temples | 57 |

| VIII | Aftermath and Decline | 65 |

| IX | The Buddhist Art of Ceylon | 75 |

| X | The Buddhist Art of Java | 90 |

| Biblography | 106 |

Sample Pages