Buddhist Iconography of Northern Bactria

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM672 |

| Author: | Kazim Abdullaev |

| Publisher: | Manohar Publishers and Distributors |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9789350980972 |

| Pages: | 274 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 10.0 inch X 6.5 inch |

| Weight | 660 gm |

Book Description

The Ancient region of Bactria lay across northern Afghanistan, South-East Tadjikistan, divided in two by the broad waters of the Amudarya. This Volume concerns that part of bactria that lay north of the river.

These lands of the foot of the river. These Lands at the Foot of the Hissar mountains, fed by major tributaries of the Amudarya, are sheltered and earliest times. They Formed part of the Achaemenid Empire and so fell to Alexander the great in the fourth century BC, an event that had a critical impact on the cultural development of the region.

The subsequent establishment of the Kushan Empire created a unique and heady blend of Indian, western and regional inufluences without parallel in the the ancient word, and through this then spread the followers of the Buddhist faith, establishing monasteries and places of worship, further enriching the architectural, sculptural and artistic traditions of the region. Despite its remarkable archaeological heritage, Physical and political realities have acted to limit the dissemination of research on northern Bactria and its Buddhist legacy, Original reports, of which there are many, are mainly in Russain or Uzbek.

This Volume brings all these many strands together in an English language work, making this important subject accessible to a wide readership. Kazim Abdullaev’s deep Knowledge of this region and its rich history brings out new analyses and insights into the extensive legacy of Buddhist traditions in northern Bactria.

Kazim Abdullaev received his Doctorate from the Moscow Institute of Archaeology in 1986. He is Specialist in the archaeology and art of central Asia of the Hellenistic and post- Hellenistic periods, a senior Fellow and Lecturer at the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul, Turkey, and a Senior Fellow of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at new York University. He has published widely in the field of Central Asian Studies and Has Participated in important field project in Uzbekistan, Turkey and Syria.

After the Buddha passed in to nirvana, his companions, it is said, followed his example and met in forests, to remember among themselves his words and deeps. Even lay adepts sometimes offered gardens for this purpose. This is believed to have taken place around the sixth century BC in India, near kapilvastu in the Ganges valley. From place to place and century after century, more stupas were built to consecrate relics of the Master, and monasteries to house the religious community in a quit environment. The earliest of these establishments in northern India are considered to date from the second century BC onwards. Westwards from the ganges valley to the Indus, Buddhist followed the already well-worn tracks of travellers and merchants from east and west. The main town was then Taxila in gandhara with its famed university . The rough crags of the Hindu Kush were not easy to cross, but they made it, nevertheless, and reached the Oxus River (Modern Amudarya ) and bactria. They began to meet unknown people from eastern and northern countries, some of them from for away China. In resting places along the trail, the Buddhist left evidence of their existence and religious practices. And religious practices. Many different ethnic tribes and greedy Conquerors had been along the same trail, leaving behind the remnants of destroyed buildings and the shattered fragments f images.

In northern Bactria, the Concern of this book, the earliest traces of the presence of the Buddhist communities can be seen by the end of the first century AD. Kazim Abdullaev has worked for the last twenty – five years on the subject of Buddhism in bactria and has collected from many sites a great volume of documentation which is presented here. This includes the large and well- studied monasteries at old Termez, Which are now the centre of the modern research. Fayaztepa and Adjinatepa illustrate a fascinating Group of local Buddhist buildings and wonderful pieces of Buddhist images, though often sadly ruined. But smaller places more lately discovered too long misunderstood or found by chance, offer unexpected proof of a much more important presence of Buddhist believers in bactria.

Both general readers and researches will find in this new book what is not so easily found in the great number of scientific reports by the very efficient specialists of these subject. Those are, for the greater part, in the very efficient specialists of these subjects. Those are, for the greater part, in the Uzbek and Russian languages and remain, of course, sources of information. The facility of a book in the English language, however, will be a great help for western readers. Thus ,this book will be a guide to new approaches and discussion on new elements concerning the difficult subject of the spread of Buddhism in western Central Asia.

GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND

Surkhandarya province - the south-eastern region of the Republic of Uzbekistan - has long attracted the attention of scholars and travellers. It has an abundance of ancient monuments located in the mountains, on the plains, and by rivers, canals, and small streams. The province occupies about 18,900 sq. km. It is bordered in the north by the majestic heights of the Hissar range, and divided into two southern regions - Surkhandarya and Kashkadarya.In the west the province is surrounded by the Baisuntau spurs and the Kugitangtau range, beyond which lies the territory of Turkmenistan. The eastern boundary of Surkhandarya is formed by the Babatag range, which also marks the border with Tajikistan. To the south, the region is bound by the Amudarya, the river that serves as the frontier with Afghanistan (Fig. 1). Between the mountain ranges, which occupy a large part of the Surkhandarya province, are two major plains, where flow the Sherabaddarya and Surkhandarya rivers, the main waterways of the province. Seasonal mountain streams caused by the melting snows feed both of these rivers. From the north, the powerful Hissar mountain range protects the Surkhandarya Valley from the cold winds, ensuring a microclimate of mild winters and hot dry summers that is similar to the subtropics. Ancient sources provide evidence of the wealth and fertility of the region. I Rich and abundant crops lured different peoples and tribes to Surkhandarya province. Nomads frequently settled here, attracted by the plentiful fruits and animals.

The Surkhandarya Valley is a narrow zone about 5 km wide, extending from north-east to south-west. The irrigated lands are located on the lowest agricultural terrace and follow the course of the Surkhandarya through the valley. In the south the valley is blocked by the Kattakum desert, created as the result of wind erosion in the semi-desert of the Khautag. The latter, together with the Utchkizil hills, separates the Surkhandarya from the Sherabaddarya Valley.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

To the north of the great ancient Oxus River, the modern Amudarya, lay an important historical and cultural area of the Orient in antiquity. Ancient historians and geographers named it Sogdiana. yet archaeological investigations of the region have demonstrated that the same culture extended on both sides of the river. Culturally, one can identify this area as Bactria (Bactriana). As a geographic border we can cite the Iron Gates near the modern village of Derbent. Much scholarly literature has been devoted to the problems of the Greco-Bactrian (Ta-Hsia of the Chinese chronicles of the first centuries BC) borders, especially their northern limits, and the state formation that followed.' After the collapse of the Greco- Bactrian kingdom this territory assumed another name based on the ethnonym of one of the large tribes, the Tokhars, who settled there." It should therefore be specified that the term North Bactria or North Tokharistan refers to the territory to the north of the Amudarya, which is bordered by the spurs of the Hissar and Baysuntau systems in the north and east respectively. Thus, the territory spread over the regions of modern Tajikistan (Kulyab and Kurgantube) and the Surkhandarya province of Uzbekistan.

During the sixth to fourth centuries BC the countries of western Asia, together with the Greek cities of Asia Minor, comprised the Achaemenid Empire. The Achaemenid Empire included also most of Central Asia, which was divided into satrapies Bactria, Sogdia ,Parthia and other are mentioned in the enumeration of conquered lands on the rock inscriptions erected by order of the Persian kings.

In 334 BC, the Greek-Macedonian army under Alexander the Great crossed the Dardanelles and from then on a new empire began to form, one no less in size than that of the Achaemenids. This event ushered in an epoch of Hellenism in the East. Within a relatively short period of time the vast expanses of Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Iran, Egypt, and Central Asia had been conquered. Nevertheless, despite the swiftness with which this huge empire was created thanks to the strategic genius of Alexander, its collapse was just as rapid after his death in 323 BC. The satrapies of Central Asia were incorporated into the Seleucid kingdom. These satrapies maintained their power until the middle of the third century BC. Almost simultaneously, Parthia (modern Turkmenistan) became independent under the local Arsacid tribe, while Bactria (comprising modern northern Mghanistan and southern Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) likewise declared her independence under the governor Diodotes." The emergence of the Greco- Bactrian kingdom that initially included both Bactria and Sogdiana reflected the flourishing of Hellenistic culture. The power of the Greco-Bactrian kings extended to include India." However, after an existence of more than 100 years Greco-Bactria (Ta Hsia of the Chinese sources) succumbed to the pressure of the nomads north of the Oxus (Amudarya) River, known in the Chinese chronicles as the Ta Yueh Chih (Da Yuezhi). 8 The Kushans, the most powerful among this group of nomads, subordinated the other four tribes, giving their name to the future state." Chinese sources of the fourth century AD mention Tokharistan (Tu-ho-lo), located on the territory of the modern Surkhandarya region, southern Tajikistan and northern and eastern parts of Afghanistan. Strabo and Justin also mention a great tribe, Tokhares, but without giving them a precise localization.

The first capital of the consolidated tribes was the city to the north of the Gui (Kuei = Oxus) River, called, in the Chinese sources. Chin-shih 11 (located hypothetically at Dal'verzintepa 12). Absorbing the traditions of the preceding periods, the Kushan Empire created a unique culture based on the colourful diversity of its people. The extent of this synthesis can be judged by the coins of Kanishka, one of the most eminent personalities of the Kushan period. Kanishka's coins display a whole gallery of different deities, Greek, Hindu, Buddhist and Zoroastrian, which aptly demonstrate his tolerant religious policy. It is also in the reign of this king that Buddhist art and culture flourished. Most scholars now accept the year AD 127 as the beginning of Kanishka's era. 13 The heyday of Kushan culture is dated to the second century and first half of the third century AD. The Kushan Empire was one of the most powerful empires in the ancient world aside from Parthia, Rome and Han China.

In the second half of the third century AD, the power of the Kushans began to decline. One of the last kings, Vasudeva II, was a contemporary of his terrible adversary Ardashir I, the founder of the Sassanian dynasty. The first of the Sassanian campaigns against the Kushans began with the march of Bahram II in AD 280 and Hormizd II (AD 303-9), and then specifically the march of Shapur II (AD 309-79), who was even married to a Kushan princess (the Sassanian rulers referred to themselves as 'Kushan shah').

Around the turn of the fifth century (AD 390-430), the territory of Northern Tokharistan passed to the power of Kidara and his successors, the Kidarites. Some coins bear the legend in Brahmi, 'Kidara Kushana sha'. Between AD 412 and 437, the Kidarites united Tokharistan with Gandhara.'' The subsequent stages in the history of Tokharistan were closely linked with the events and peoples of the surrounding regions. The sources mention these peoples as Kidarites and Chionites - Hephthalites.'? In the second half of the fifth century, the Hephthalites entered the historical arena as a mighty force. Historians recounted brilliant episodes of fighting between the Sassanian King Peroz (AD 459-84) and the Hephthalites. For Peroz, the war was not successful. His successor, the Sassanian King Khosrov I (AD 531-78), was luckier. He made a very strong alliance with the Turkic Kaghanate. In the middle of the sixth century, the consolidation of Turkic tribes, who initially inhabited the area around the Altai, presented a new and menacing force moving towards the borders of Central Asia. Thus, the Hephthalites found themselves caught between the Turks and Sassanians.

| List of Figure | 7 | |

| Foreword: Francine Tissot | 17 | |

| Editors' Preface: Alision Betts and Fiona Kidd | 19 | |

| Acknowledgement | 21 | |

| Glossary | 23 | |

| Abbreviations | 29 | |

| 1 | Introduction | 31 |

| Grographical Background | 31 | |

| Historical Background | 31 | |

| History of Research | 35 | |

| 2 | The Traditional of Plastic Art in Northern | |

| Bactria-Tokharistan | 39 | |

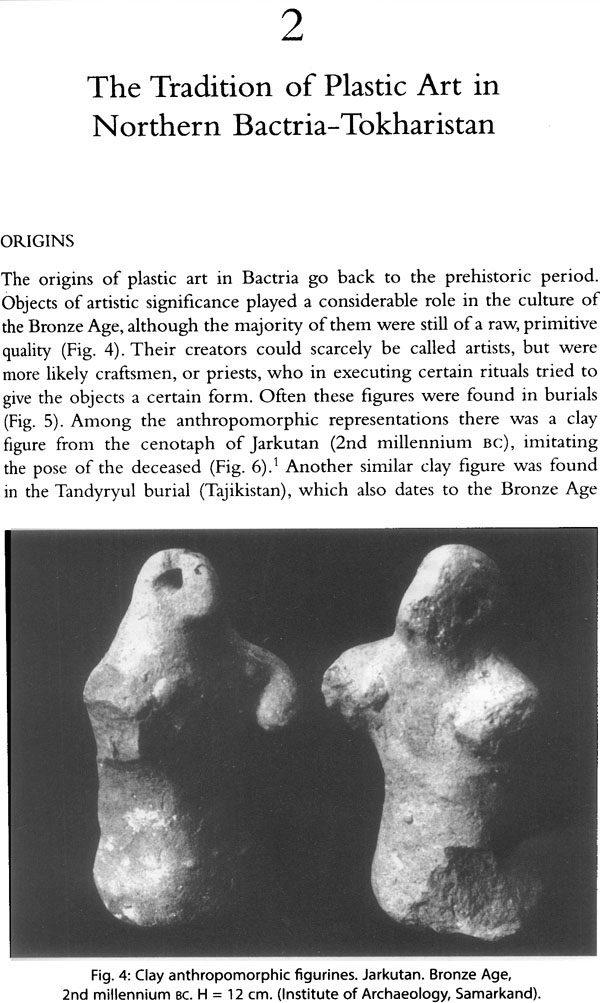

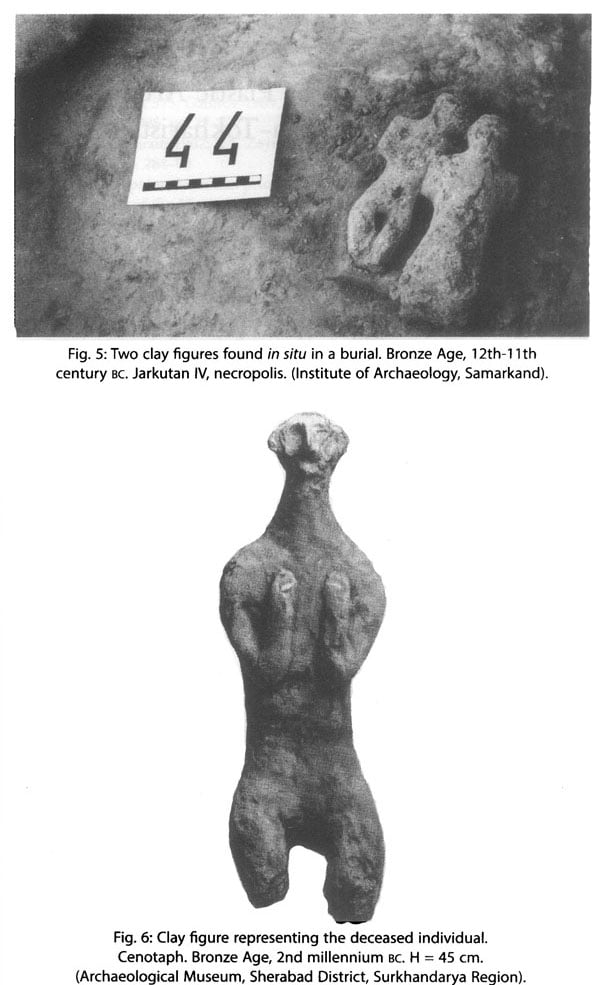

| Orgins | 39 | |

| The Hellenistic Period | 48 | |

| Ai Khanoum | 48 | |

| Takht-I Sangin | 53 | |

| The Hellenistic and Yue-zhi Periods | 58 | |

| Khalchayan | 58 | |

| The Kushan Period | 67 | |

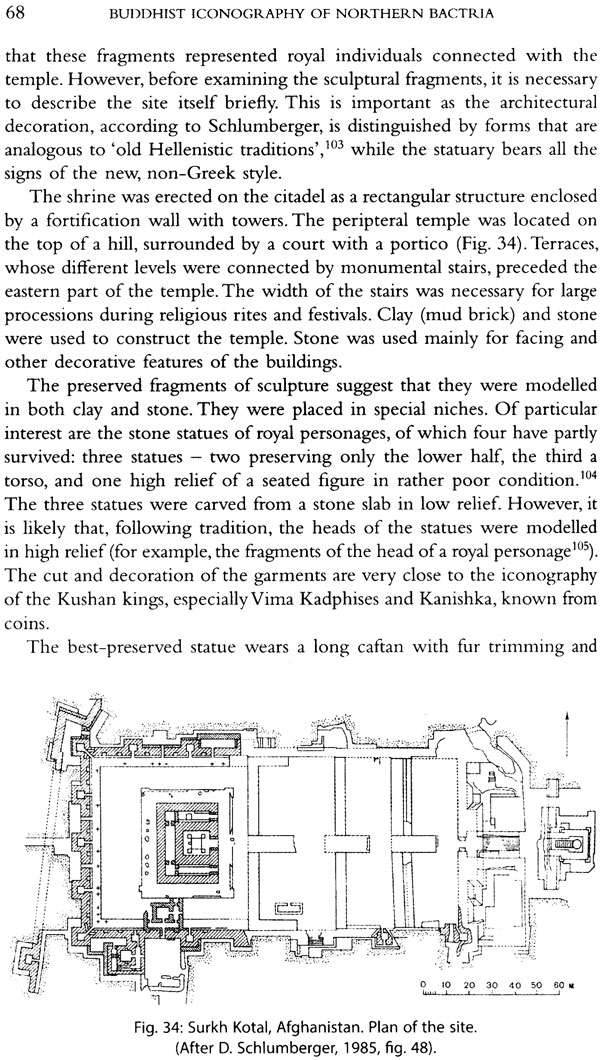

| Surkh Kotal | 67 | |

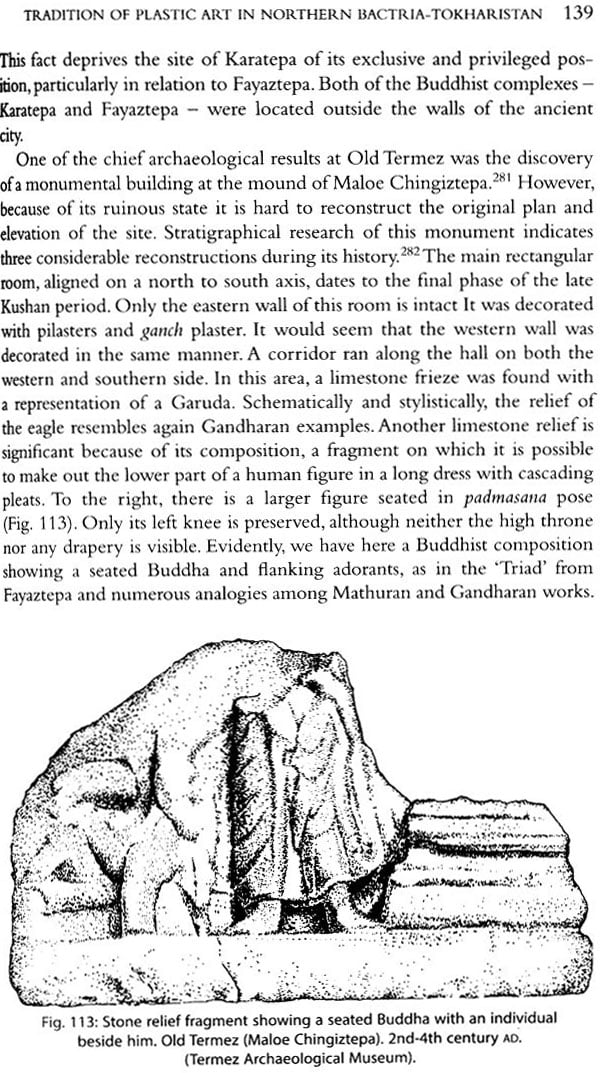

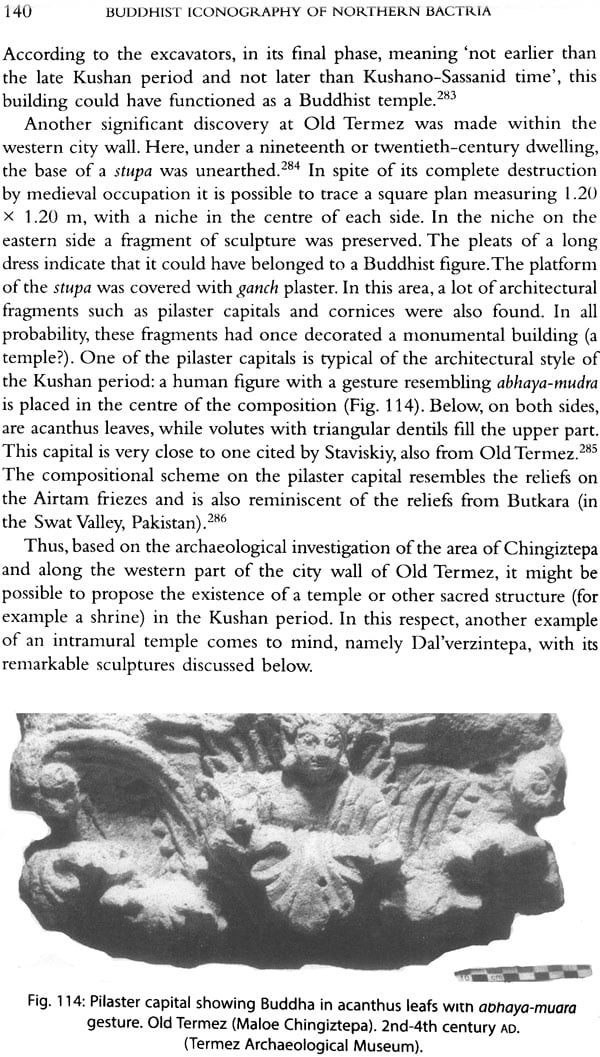

| Old Termez | 71 | |

| Buddhist Terracotta Plastic Art | 85 | |

| Fayaztepa | 106 | |

| Karatepa | 118 | |

| Airtam | 141 | |

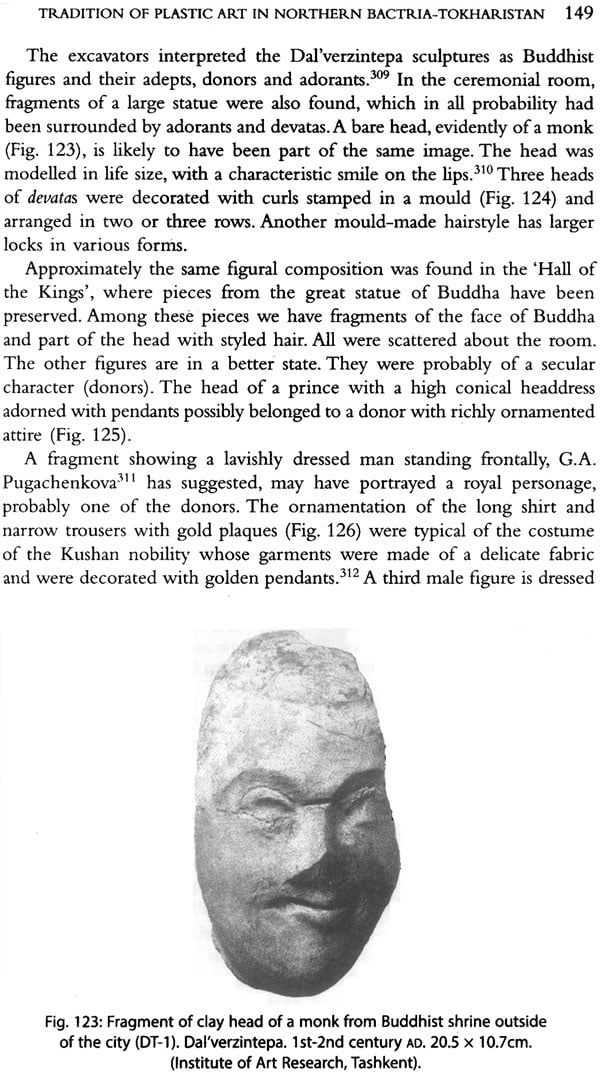

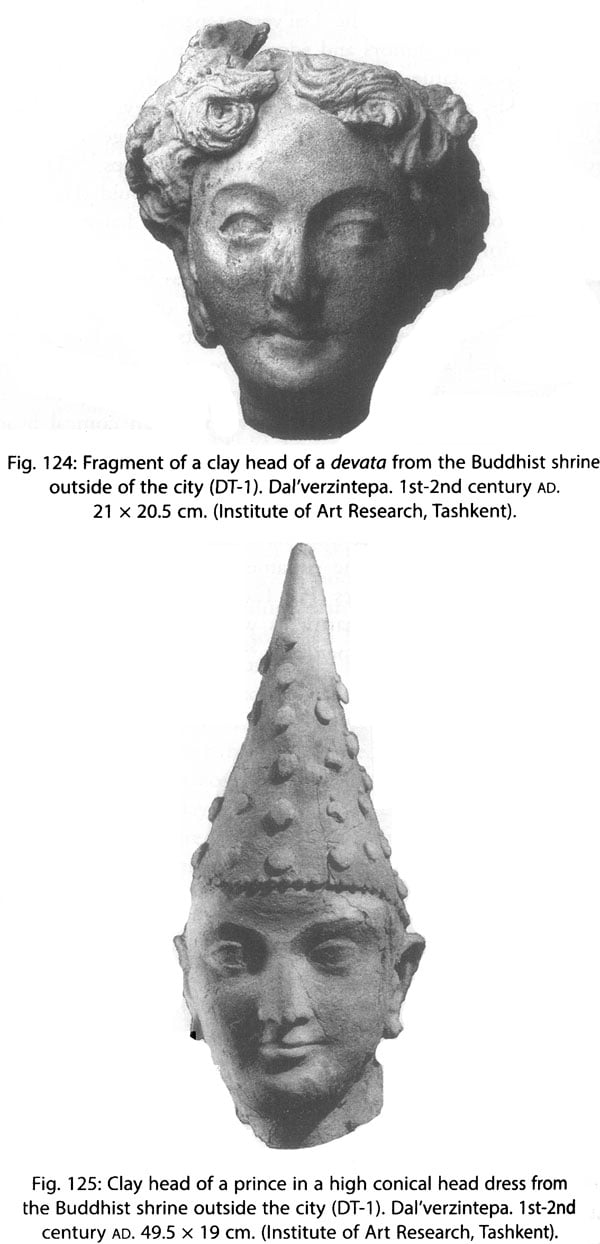

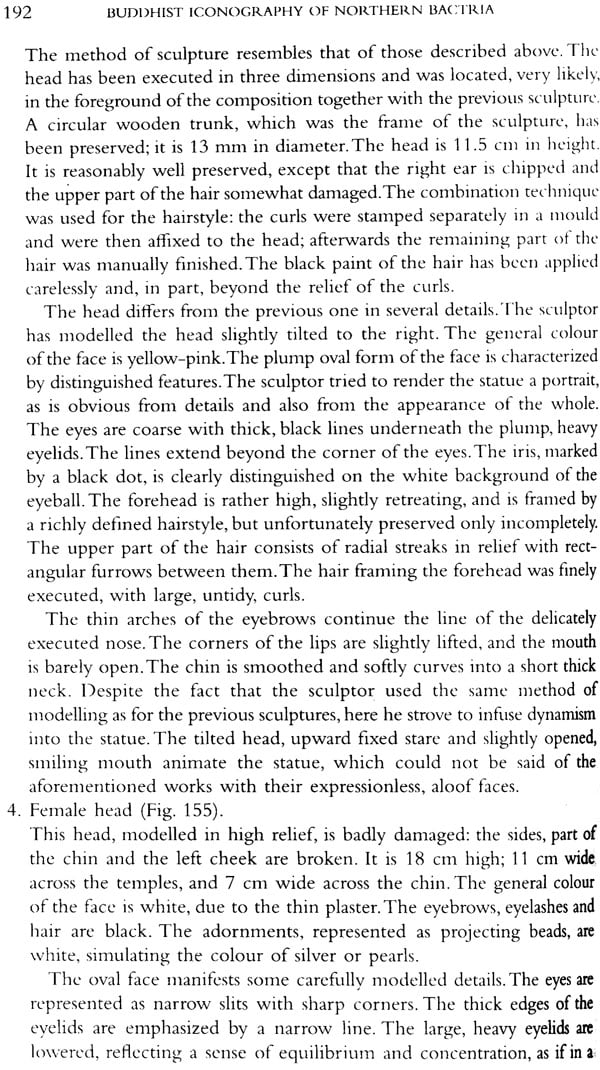

| Dal Verzintepa | 146 | |

| The Terracotta from Khatynrabat and the Problem of Japinism Bactria | 164 | |

| Objects of Buddhist Plastic art From Neighbouring Historic - Cultural Regions | 166 | |

| Bodhisattva from Ekurgan | 169 | |

| The early Medieval Period ( Late Fourth to Fifth Century AD ) | 177 | |

| The Provincial Estate of Kuevkuragan | 177 | |

| Kuevkurgan and Zartepa | 210 | |

| The Traditional of Buddhist Art in the Early Medival Period (Ushtur- Mullo and Ajinatepa) | 216 | |

| Kalai Kafirnigan | 226 | |

| Hisht - tepa | 229 | |

| Buddhist Monuments in Margiana | 231 | |

| Kuva | 233 | |

| The Buddhist Complex of Ak Beshim and Krasnorechensoke | 237 | |

| 3 | Conclusion | 253 |

| Bibliography | 255 | |

| Index | 271 |