Buddhist Parables

Book Specification

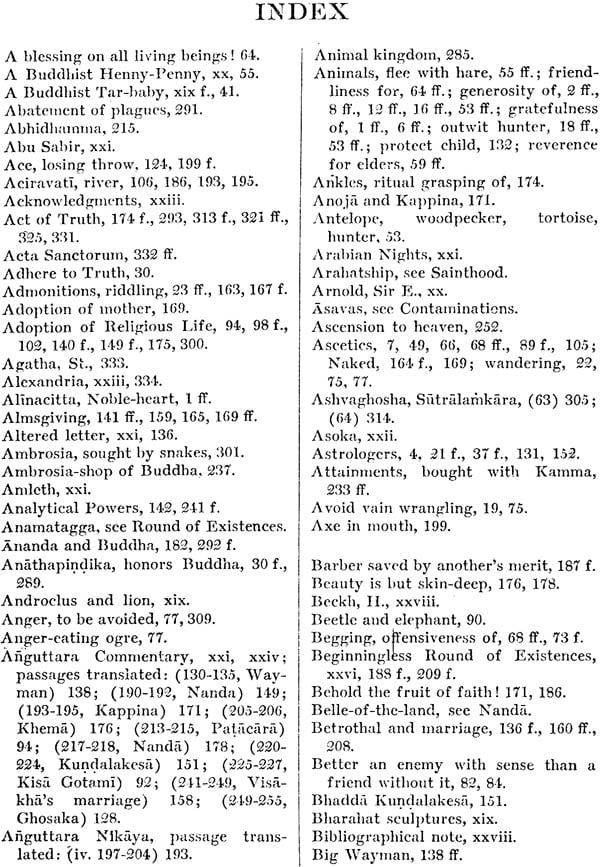

| Item Code: | IDC141 |

| Author: | Engene Watson Burlingame |

| Publisher: | Pilgrims Book Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | Translated from the Original Pali |

| Edition: | 1994 |

| ISBN: | 8120807383 |

| Pages: | 377 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5" X 5.4" |

| Weight | 350 gm |

Book Description

Preface

This volume contains upwards of two hundred similes, allegories, parables, fables, and other illustrative stories and anecdotes, found in the Pali Buddhist texts, and said to have been employed, either by the Buddha himself or by his followers, for the purpose of conveying religious and ethical lessons and the lessons of common sense. Much of the material has never before been translated into English.

Chapters I-III contain parables drawn, with a single exception, from the Book of the Buddha's Previous Existences, or Jataka Book. This remarkable work relates in mixed prose and verse the experiences of the Future Buddha, either as an animal or as a human being, in each of 550 states of existence previous to his rebirth as Gotama. The textus receptus of this work represents a recension made in Ceylon early in the fifth centuries A.D., but much of the material is demonstrably many centuries older. For example, the stanzas rank as Canonical Scripture, and many of the stories (including Parables 4 and 14 and 27) are illustrated by Bharahat sculptures of the middle of the third century B.C. Parable 6 is taken from the Book of Discipline or Vinaya, and was very possibly related by the Buddha himself.

With Parable 1, The grateful elephant, compare the story of Androclus and the lion, and Gesta Romanorum 104. With Parable 2, Grateful animals and ungrateful man, compare E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 25; A. Scheifner, Tibetan Tales 26; Gesta Romanorum 119; and the following stories in Grimm, Kinder-und Hausmarchen: 17 Die Goldkinder, 107 Die beiden Wanderer, 126 Ferenand getru un Ferenand ungetru, 191 Das Meerhaschen. For additional parallels, see J. Bolte und G. Polivka, Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- und Hausmarchen der Bruder Grimm, Marchen 17, 62, 191.

Parable 9, Vedabbha and the thieves, is the original of Chaucer's Pardoner's Tale. With Parable 10, A Buddhist Tar-baby, compare E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 89 and 410; also the well-known story in Joel Chandler Harris, Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings. With Parable 13, Part 1, Gem, hatchet, drum, and bowl, compare Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmarchen: 36 Tischchen deck dich, Goldesel, und Knuppel aus dem Sack; 54 Der Ranzen, das Hutlein, und das Hornlein. For additional parallels, see Bolte-Polivka. A more primitive form of Parable 15, A Buddhist Henny-Penny, will be found in A. Schiefneer, Tibetan Tales 22. Compare the well-known children's story of the same name. Parables 5 and 14 are the oldest known prototypes of Panchatantra, Book 2, Frame-story.

Chapter IV contains four specimens of Jataka parables in early and late forms. Compare also Chapter II, Parables 6 and 7; and Chapter VIII, Parables 45 and 47, with Chapter III, Parables 8 and 11, respectively. The reader will observe that in the earlier (Canonical) versions, the Future Buddha has not yet become identified with any of the dramatis personae. This material is offered as a contribution to the history of the evolution of the Buddhist Parable.

Chapter V contains four remarkably fine old parables which may well have been related by the Buddha himself.

Chapter VI contains several typical specimens of a variety of parable which will undoubtedly be new to many students of religious literature-the Humorous Parable.

Chapter VII contains several specimens of Parables on Death. With Parable 30, Kisa Gotami, compare E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 224; Budge, Ethiopic Pseudo-Callisthenes, pp. 306-308, 374-376; Sir Edwin Arnold, Light of Asia, Book 5; John Hay, Poems, The Law of Death. A modern Burmese version of Parables 30 and 31 combined will be found in H. Fielding Hall, Soul of a People, pp. 272-278. For a Tibetan version of Parable 31, Patacara, see Tibetan Tales, pp. 222-226. Parable 31 is one of the three principal sources of the legend of St. Eustace, the other history of this legend, see H. Delehaye, La legende de saint Eustace, Bull. De l'Acad. Roy. De Belgique (Classe des lettres), 1919, pp. 175-210. Compare the history of Faustus, Faustinus, and Faustianus, in the Clementine Recognitiones, 200 A.D. (outline in dict Chr. Biog., i. 569-570); Gesta Romanorum 110; Golden Legend, St. Eustace; Early English metrical romance of Sir Ysumbras; and the story of Abu Sabir in the Arabian Nights (Burton, Supplemental Nights, i. 81-88).

Chapter VIII contains, in the form of an imaginary dialogue between an unbeliever and the Buddhist sage Kumara Kassapa, a lengthy discussion of the subject: "Is there a life after death?" In order to refute objections advanced by the unbeliever, the sage relates thirteen remarkably fine parables, finally vanquishing his antagonist. The arguments pro and con are the same that have been used ever since men began to discuss this important subject. The dialogue forms one of the chapters of the Long Discourses, one of the oldest of the Buddhist books, but is quite modern in its freshness.

Chapter IX contains several parables from a commentary on the Anguttara Nikaya composed by Buddhaghosa in the early part of the fifth century A.D. The first two parables in Chapter VII are from the same source. Parallels from a commentary on the Dhammapada composed by a contemporary of Buddhaghosa will be found in the author's Buddhist Legends.

Parable 49, Ghosaka, has traveled all over the world. For the principal Oriental versions, see J. Schick, Corpus Hamleticum, Berlin, 1912. For an interesting Chinese Buddhist version, see E. Chavannes, Cinq Cents Contes 45. This story appears to be the source of the ninth century apocryphal legend of the seven marvels attending the birth of Zoroaster; se the author's paper in Studies in Honor of Maurice Bloomfield, pp. 105-116. For some interesting European derivatives, see Gesta Romanorum 20 and 283; Golden Legend, Pope St. Pelagius; William Morris, Old French Romances, Kinig Coustans the Emperor (thirteenth century); Schiller's ballad Fridolin; Grimm, Kinder- und Haus-marchen, 29 Der Teufel mit den drei goldenen Haaren. For additional derivatives, see Bolte-Polivka, i. 286-288. The story of Amleth in the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus contains two derivatives, of which one is utilized by Shakespeare in Hamlet.

Chapter X is a miscellaneous collection of parables from early sources. These parables are all much older than the beginning of the Christian era, and it is altogether probable that some of them, more particularly Parables 57, 58, 59, 60, 63, and 65, enshrine the very words of the Buddha himself is one,-Professor Charles Rockwell Lanman of Harvard University, Professor Maurice Bloomfield of the Johns Hopkins University, and the late Professor Morris Jastrow of the University of Pennsylvania. Through his exercises in the Fables of Bidpai, the late Professor Jastrow first opened my eyes to the immense possibilities of this body of literature. In innumerable ways, such as will readily suggest themselves to those who knew him well, he assisted me in my work, and through his untimely death I have suffered a profound personal loss. Under Professor Bloomfield I studied for many years, and through his exercises in the Vedas, in the fiction-collections of India, and in Comparative Grammar, laid the foundations of a sound philological method. Professor Lanman first opened the Pali texts to me, and did more than any other to assist me to interpret them. It is not only a duty but a pleasure to record my indebtedness to these three distinguished scholars.

I wish also to thank Professor E. Washburn Hopkins of Yale University for a careful review of the manuscript of the present work, and for many helpful suggestions.

I am greatly indebted to M. Andrew Keogh, Librarian of Yale University, and to Mr. James I. Wyer, Director of the New York State Library, for generous facilities accorded me in the loan of books. I am also under obligations to Professor Lanman for the loan of a rare copy of Buddhaghosa's Anguttara Commentary, Colombo, 1904. It is from this text that the translation of Buddhaghosa's Legends of the Saints have been made.

I have to thank Mr. Langdon Warner, Director of the Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, for permission to reproduce the beautiful Graeco-Buddhist head which forms the frontispiece to the present volume.

Last, but by no means least, my most hearty thanks are due to Mr. George Parmly Day, President of the Yale University Press, for invaluable assistance rendered in connection with the execution and publication of the book.

Back of the Book

This book contains upwards of two hundred similes, allegories, parables, fables and other illustrative stories and anecdotes, found in the Pali Buddhist texts, and said to have been employed, either by the Buddha himself or by his followers, for the purpose of conveying religious and ethical lessons and the lessons of common sense.

The book is thus a collection of specimens of an unusually interesting type of literary composition; a text-book of the teachings of the Buddha, presented just as the Buddha and his followers presented them, by discourse and example; and a collection of good stories, all in one. It contains much that will interest children; it also contains much that will puzzle the profoundest philosopher.

Introductory Note

Gotama Buddha was born nearly twenty-five centuries ago in the city of Kapila, in North-East India. Kapila was the principal city of the Sakya tribe, and his father was king of the tribe. Gotama was his family name. Buddha means Awakened or Enlightened, that is to say, awakened or enlightened to the cause and the cure of human suffering.

The Buddhist Scriptures tell us that when Gotama was born, the agnels rejoiced and sang. An aged wise man inquired: "Why doth the company of angels rejoice?" They replied: "He that shall become Buddha is born in the village of the Sakyas for the welfare and happiness of mankind; therefore are we joyful and exceeding glad."

The wise man hastened to the king's house, and said: "Where is the child? I, too, wish to see him." They showed him the child. When he saw the child, he rejoiced and was exceeding glad. And he took him in him arms, and said: "Without an equal is he! foremost among men!" Then, because he was an old man, and knew that he was soon to die, he became sorrowful and wept tears.

Said the Sakyas: "Will any harm come to the child?" "No," replied the wise man, "This child shall one day become Buddha; out of love and pity for mankind he shall set in motion the Wheel of Religion; far and wide shall his religion be spread. But as for me, I have not long to live; before these things shall come to pass, death will be upon me. Therefore am I stricken with woe, over-whelmed with sorrow, afflicted with grief."

Seven days after Gotama was born, his mother died, and he was brought up by his aunt and stepmother. When he was nineteen years old, he married his own cousin. For ten years he lived a life of ease, in the enjoyment of all the comforts and luxuries which riches and high position could give him. When he was twenty-nine years old, a change came over him.

For many centuries, it has been a common belief in India that when a human being dies, he is at once born again. If he has lived a good life, he will be born again on earth as the child of a king or of a rich man, or in one of the heavens as a god. If he has lived an evil life, he will be born again as a ghost, or as an animal, or in some place of torment.

According to this belief, every person has been born and has lived and died so many times that it would be impossible to count the number. Indeed, so far back into the past does this series of lives extend that it is impossible even to imagine a beginning of the series. What is more to the point, in each of these lives every person has endured much suffering and misery.

Said the Buddha: "In weeping over the death of sons and daughters and other dear ones, every person, in the course of his past lives, has shed tears more abundant than all the water contained in the four great oceans."

And again: "The bones left by a single person in the course of his past lives would form a pile so huge that were all the mountains to be gathered up and piled in a heap, that heap of mountains would appear as nothing beside it."

And again" "The head of every person has been cut off so many times in the course of his past lives, either as a human being or as an animal, as to cause him to shed blood more abundant than all the water contained in the four great oceans."

Nothing more terrible than this can be imagined. Yet for many centuries it has been a common belief in India. Wise men taught wished to avoid repeated lives of suffering and misery, he must leave home and family and friends, become a monk, and devote himself to fasting, bodily torture, and meditation.

The Buddhist Scriptures tell us that when Gotama was twenty-nine years old, he saw for the first time an Old Man, a Sick Man, a Dead Man, and a Monk. The thought that in the course of his past lives he had endured old age, sickness, and death, times without number, terrified him, and he resolved to become a monk.

Leaving home and wife and son, he devoted himself for six years to fasting, bodily torture, and meditation. Finally he become convinced that fasting and bodily torture were not the way of salvation, and abandoned the struggle. One night he had a wonderful experience. First he saw the entire course of his past lives. Next he saw the fate after death of all living beings. Finally he came to understand the cause of human suffering and the cure for it.

Thus it was that he became Buddha, the Awakened, the Enlightened. He saw that the cause of rebirth and suffering was craving for worldly pleasures and life and riches. He saw that if this craving were uprooted, rebirth and suffering would come to an end. He saw that this craving could be uprooted by right belief, right living, and meditation.

For forty-five years the Buddha journeyed from place to place, preaching and teaching. He founded an order of monks and nuns, and won many converts. He lived to be eighty years old. Missionaries carried his teachings from India to Ceylon and Burma and China and Tibet and Japan. In a few hundred years the religion of the Buddha had spread over the whole of Asia. Hundreds of millions of human beings have accepted his teachings.

In at least two respects, the teachings of the Buddha were quite remarkable. In the first place, he insisted on the virtue of moderation. He urged upon his hearers to avoid the two extremes of a life devoted to fasting and self-torture and a life of self-indulgence. In the second place, he taught that a man must love his neighbor as himself, returning good for evil and love for hatred. But this was not all. He taught men to love all living creatures without respect of kind or person. He taught men not to injure or kill any living creature, whether a human being or an animal, even in self-defense. All war, according to the teaching of the Buddha, is unholy.

In the course of time it came to be believed that Gotama had become Buddha as the fruit of good deeds performed in countless previous states of existence, especially deeds of generosity. At any time, had he so desired, he might have uprooted craving for worldly pleasures and life and riches by meditation, and thus have escaped the sufferings of repeated states of existence. But this he deemed an unworthy course. Out of pity and compassion and friendliness for living creatures, he preferred to be reborn again and again, to suffer and to die again and again, in order that, by the accumulated merit of good works, he might himself become enlightened and thus be able to enlighten others.

In comparison with the career of the Future Buddha, devoted to the performance of good works, unselfish, generous to the point of sacrificing his own body and blood, the career of the monk, isolated from the world, selfish, seeking by meditation to uproot craving for worldly pleasures and life and riches, seemed low and mean. The disciple began to imitate his Master. Thus began the Higher Career or Vehicle of Mahayana or Catholic Buddhism, as distinguished from the Lower Career or Vehicle of the more primitive Hinayana Buddhism of the Pali texts. Thus did the quest of Buddhahood supplant the quest of Nibbana. This development took place long before the beginning of the Christian era.

| Preface | xix | |

| Acknowledgements | xxiii | |

| Introductory Note | xxv | |

| Note on Pali Names | xxviii | |

| Bibliographical Note | xxviii | |

| Chapter I. | Parables from the Book of the Buddha's Previous Existences on the gratefulness of animals and the ungratefulness of man | |

| 1. | The grateful elephant | 1 |

| Where there's a will, there's a way | ||

| 2. | Grateful animals and ungrateful man | 6 |

| Driftwood is worth more than some men | ||

| 3. | Elephant and ungrateful forester | 11 |

| The whole earth will not satisfy an ungrateful man | ||

| Chapter II. | Parables from the Book of the Buddha's Previous Existences and from the Book of discipline, on unity and discord | |

| 4. | Quail, crow, fly, frog, and elephants | 16 |

| The biter bit | ||

| 5. | Quails and fowler | 18 |

| In union there is strength | ||

| 6. | Brahmadatta, Dighiti, and Dighavu (cf. 7) | 20 |

| Love your enemies | ||

| 7. | Dighavu and the king of Benares (cf. 6) | 28 |

| Love your enemies | ||

| Chapter III. | Parables from the Book of the Buddha's Previous Existences on divers subjects | |

| 8. | Two caravan-leaders (cf. 45) | 30 |

| Adhere to the Truth | ||

| 9. | Vedabbha and the thieves | 36 |

| Cupidity is the root of ruin | ||

| 10. | A Buddhist Tar-baby (cf. 21) | 41 |

| Keep the Precepts | ||

| 11. | Two dicers (cf. 47) | 44 |

| Take care | ||

| 12. | Brahmadatta and Mallika | 45 |

| Overcome evil with good | ||

| 13. | King Dadhivahana | |

| Evil communications corrupt good manners | ||

| Part 1. Gem, hatchet, drum, and bowl | 49 | |

| Part 2. Corrupt fruit from a good tree | 51 | |

| 14. | Antelope, woodpecker, tortoise, and hunter | |

| In union there is strength | ||

| 15. | A Buddhist Henny-Penny | 55 |

| Much ado about nothing | ||

| Chapter IV. | Parables from the Book of the Buddha's Previous Existences in early and late forms | |

| 16. | Partridge, monkey, and elephant | |

| Reverence your elders | ||

| A. Canonical version | 59 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | 60 | |

| 17. | The hawk | |

| Walk not in forbidden ground | ||

| A. Canonical version | 62 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | 68 | |

| 18. | Snake-charm | |

| A blessing upon all living beings! | ||

| A Canonical version | 64 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | 66 | |

| 19. | Dragon Jewel-neck (cf. 20) | |

| Nobody loves a beggar | ||

| A. Canonical version | 68 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | 70 | |

| Chapter V. | Parables from early sources on divers subjects | |

| 20. | The birds (cf. 19) | 73 |

| Nobody loves a beggar | ||

| 21. | The monkey (cf. 10 and 17) | 74 |

| Walk not in forbidden ground | ||

| 22. | Blind men and elephant | 75 |

| Avoid vain wrangling | ||

| 23. | The anger-eating ogre | 77 |

| Refrain from anger | ||

| Chapter VI. | Humorous parables from early and late sources | |

| 24. | Mistress Vedehika | 79 |

| Patient is an patient does | ||

| 25. | Monkey and dyer | 81 |

| The Doctrine of the Buddha wears well | ||

| 26. | How not to hit an insect | |

| Better an enemy with sense than a friend without it | ||

| A. Boy and mosquito | 82 | |

| B. Girl and fly | 84 | |

| 27. | Monkey-gardeners | |

| Misdirected effort spells failure | ||

| A. One-stanza version | 85 | |

| B. Three-stanza version | 87 | |

| 28. | Boar and lion | 89 |

| Touch not pitch lest ye be defiled | ||

| 29. | Beetle and elephant | 90 |

| Pride goeth before a fall | ||

| Chapter VII. | Parables from various sources on death | |

| 30. | Kisa Gotami | 92 |

| There is o cure for death | ||

| 31. | Patacara | 94 |

| Kinsfolk are no refuge | ||

| 32. | The Heavenly Messengers | |

| Prepare for death | ||

| Part 1. Makhadeva | 97 | |

| Part 2. Nimi | 99 | |

| 33. | Upasalhaka | 104 |

| Cremated fourteen thousand times in one place ! | ||

| 34. | Ubbiri | 106 |

| Why weep for eighty-four thousand daughters? | ||

| 35. | Visakha's sorrow | 107 |

| So many dear ones, so many sorrows | ||

| Chapter VIII. | Parables from the Long Discourses on the subject: "Is there a life after death?" | |

| The wicked do not return to earth | 109 | |

| 36. | The condemned criminal | 110 |

| The virtuous do not return to earth | 110 | |

| 37. | The man in the dung-pit | 111 |

| The virtuous do not return to earth | 112 | |

| 38. | Time in heaven | 113 |

| How do we know that the gods exist? | 113 | |

| 39. | The blind man | 113 |

| Why do not the virtuous commit suicide? | 114 | |

| 40. | The woman with child | 115 |

| We cannot see the soul after death | 116 | |

| 41. | We cannot see the soul during life | 116 |

| The dead are heavier than the living | 116 | |

| 42. | Heat makes things light | 117 |

| We cannot see the soul | 117 | |

| 43. | Villagers and trumpet | 118 |

| We cannot see the soul | 119 | |

| 44. | The search for fire | 119 |

| Wilful persistence in error | 121 | |

| 45. | Two caravan-leaders (cf. 8) | 121 |

| Wilful persistence in error | 123 | |

| 46. | Dung for fodder | 124 |

| Wilful persistence in error | 124 | |

| 47. | Two dicers (cf. 11) | 124 |

| Wilful persistence in error | 125 | |

| 48. | Giving up better for worse | 125 |

| Conversion of the unbeliever | 126 | |

| Chapter IX. | Parables from Buddhaghosa's Legends of the Saints | |

| 49. | Ghosaka | |

| He that diggeth a pit shall fall into it | ||

| A. Story of the Past: A father casts away his son | ||

| B. Story of the Present: Ghosaka is cast away seven times | 130 | |

| 50. | Little Wayman | |

| The last shall be first | ||

| A. Birth of Little Wayman | 133 | |

| B. Little Wayman as a monk | 140 | |

| C. Story of the Past: The mouse-merchant | 143 | |

| 51. | Nanda the Elder | |

| Giving up worse for better | ||

| A. Canonical version | 146 | |

| B. Uncanonical version | 149 | |

| 52. | Bhadda Kundalakesa | 151 |

| Quick is the wit of woman | ||

| 53. | Visakha's marriage | 158 |

| Honor the household divinity | ||

| 54. | King Kappina and Queen Anoja (cf. 62) | 171 |

| Behold the fruit of faith | ||

| 55. | Khema (cf. 56) | 176 |

| Beauty is but skin-deep | ||

| 56. | Nanda (cf. 55) | 178 |

| Beauty is but skin-deep | ||

| Chapter X. | Parables from early sources on the Doctrine | |

| 57. | The sower | 180 |

| Like the soil of the earth is the soil of the heart | ||

| 58. | The Buddha and Ananda | 182 |

| Whoever walks in righteousness, honors the Buddha | ||

| 59. | The Buddha and Vakkali | 182 |

| Whoever sees the Truth, sees Me | ||

| Whoever sees Me, sees the Truth | ||

| 60. | The Buddha and the sick man | 184 |

| He that would wait upon Me, let him wait upon the sick | ||

| 61. | The snake | 185 |

| Grasp the Scriptures aright | ||

| 62. | Walking on the water (cf. 54) | 186 |

| Behold the fruit of faith ! | ||

| 63. | The Beginninigless Round of Existences (cf. 78-80) | 188 |

| Uproot Craving, the Eye of Existence | ||

| 64. | The relays | 190 |

| The Religious Life is only a means to an end | ||

| 65. | The Great Ocean | 193 |

| The Doctrine Tastes only of Deliverance | ||

| 66. | The Buddha and the herdsman Dhaniya | 197 |

| So If thou wilt, rain, O god | ||

| 67. | The axe in the mouth | 199 |

| Every man is born with an axe in his mouth | ||

| Chapter XI. | Similes and short parables from the Questions of Milinda | |

| 1. There is no permanent individuality | 201 | |

| 68. | Chariot | 202 |

| 2. There is no continuous personal identity | 204 | |

| 69. | Embryo and child | 204 |

| 70. | Lamp and flame | 205 |

| 71. | Milk and butter | 205 |

| 3. What, then, is reborn? | 206 | |

| Name-and-Form is reborn | 206 | |

| 72. | Theft of mangoes | 206 |

| 73. | Fire in a field | 207 |

| 74. | Lamp under a thatch | 207 |

| 75. | Girl and woman | 208 |

| 76. | Milk and curds | 208 |

| What is Name and what is Form? | 209 | |

| 77. | Gem and egg | 209 |

| 4. Time has no beginning (cf. 63) | 209 | |

| 78. | Seed and fruit | 210 |

| 79. | Egg and hen | |

| 80. | Circle. | 210 |

| 81. | Timbers and house | 211 |

| 82. | Seeds and plants | 211 |

| 83. | Clay and vessels | 211 |

| 84. | Lyre and sound | 211 |

| 85. | Fire-drill and fire | 212 |

| 86. | Burning-glass and fire | 212 |

| 87. | Mirror and reflection | 212 |

| 6. There is no soul | 213 | |

| 88. | Six Doors of the Senses | 213 |

| 89. | Men in palace | 213 |

| 90. | Man outside of gateway | 214 |

| 91. | Man in trough of honey | 214 |

| 7. Why does ot the fire of Hell destroy the of Hell? | 215 | |

| 92. | Embryo of reptiles and birds | 215 |

| 93. | Embryo of beasts of prey | 216 |

| 94. | Human embryo | 216 |

| 8. Nibbana is unalloyed bliss | 217 | |

| 95. | Bliss of sovereignty | 218 |

| 96. | Bliss of knowledge | 218 |

| 9. Nibbana is unlike anything else | 219 | |

| Unlike anything else also are: | ||

| 97. | The great ocean | 219 |

| 98. | The Gods without form | 220 |

| But it has the following qualities: | ||

| 99. | One quality of he lotus | 221 |

| 100. | Two qualities of water | 221 |

| 101. | Three qualities of medicine | 222 |

| 102. | Four qualities of the great ocean | 222 |

| 103. | Five qualities of food | 222 |

| 104. | Ten qualities of space | 223 |

| 105. | Three qualities of the wishing-jewel | 223 |

| 106. | Three qualities of red-sandalwood | 223 |

| 107. | Three qualities of the cream of ghee | 224 |

| 108. | Five qualities of a mountain-peak | 224 |

| 10. Nibbana is neither past nor future nor present | 224 | |

| It is neither produced nor not produced nor to be produced. Yet it exists, and may be realized | ||

| 109. | Escape from a bon-fire | 225 |

| 110. | Escape from a heap of corpses | 225 |

| 111. | Escape from peril | 226 |

| 112. | Escape from mud | 226 |

| 113. | Red-hot iron ball | 227 |

| 114. | Bon-fire | 227 |

| 115. | Traveler who has lost his way | 228 |

| 11. Nibbana is not a place | 228 | |

| 116. | fields and crops | 228 |

| 117. | Fire-sticks and fire | 229 |

| 118. | Seven Jewels of a King | 229 |

| 12. How do we know that the Buddha ever existed? | 230 | |

| How do we know that Kings existed of old? | 230 | |

| So is it in the case of the Buddha | 231 | |

| 119. | The builder of a city is known by his city | 231 |

| 120. | So is the Buddha known by his City of Righteousness | 232 |

| Seven Shops of the Buddha: | 233 | |

| 121. | Flower-shop | 233 |

| 122. | Perfume-shop | 233 |

| 123. | Fruit-shop | 234 |

| 124. | Buyer and seller of mangoes | 235 |

| 125. | Medicine-shop | 235 |

| 126. | Herb-shop | 236 |

| 127. | Ambrosia-shop | 237 |

| 128. | Jewel-shop | 237 |

| Seven Jewels of the Buddha: | 238 | |

| 129. | Morality | 238 |

| 130. | Concentration | 238 |

| 131. | Wisdom | 239 |

| 132. | Deliverance | 240 |

| 133. | Insight | 240 |

| 134. | Analytical Powers | 241 |

| 135. | Prerequisites of Enlightenment | 242 |

| 136. | General shop | 243 |

| 13. The Pure Practices | ||

| 137-162. | Twenty-six similes | 244 |

| Chapter XII. | Parables from the Long Discourses on the Fruits of the Religious Life | |

| Removal of the Five Obstacles | 246 | |

| 163. | Payment of a debt | 246 |

| 164. | Recovery from a sickness | 247 |

| 165. | Release from prison | 247 |

| 166. | Emancipation from slavery | 247 |

| 167. | Return from a journey | 248 |

| The Four Trances | 248 | |

| first Trance | 248 | |

| 168. | Ball of lather | 249 |

| Third Trance | 249 | |

| 169. | Pool of water (cf. 179 and 203) | 249 |

| Third Trance | 250 | |

| 170. | Lotus-flowers | 250 |

| Fourth Trance | 250 | |

| 171. | Clean garment | 250 |

| Insight | 251 | |

| 172. | Threaded gem | 251 |

| Creation of a Spiritual Body | 251 | |

| 173. | Reed, sword, snake | 252 |

| The Six Supernatural Powers | 252 | |

| 174. | Potter, ivory-carver, goldsmith | 253 |

| The Heavenly Ear | 253 | |

| 175. | Sounds of Drums | 253 |

| Mind-reading | 253 | |

| 176. | Reflection in a mirror | 254 |

| Recollection of previous states of existence | 254 | |

| 177. | Recollection of a journey | 254 |

| The Heavenly Eye | 255 | |

| 178. | Mansion at cross-roads | 255 |

| Knowledge of the means of destroying the three Con taminations: Nibbana | 256 | |

| 179. | Pool of water (cf. 169 and 203) | 256 |

| Chapter XIII. | Parables from the medium-length Discourses on two kinds of herdsmen | |

| 180. | Mara, the Wicked Herdsman | 253 |

| Destruction of the Eye of Mara | 263 | |

| The Four Trances | 263 | |

| Knowledge of the means of destroying the taminations | 264 | |

| 181-183. | The Buddha, the Good Herdsman I | 264 |

| How Gotama mastered his thoughts | 265 | |

| 181. | Herd of cows | 265 |

| How Gotama concentrated his thoughts | 266 | |

| 182. | Herd of cows | 266 |

| How Gotama attained Enlightenment | 267 | |

| The Four Trances | 267 | |

| Recollection of previous states of existence | 267 | |

| The Heavenly Eye | 268 | |

| Knowledge of the means of destroying the Three Contaminations | 268 | |

| 183. | Herd of deer | 269 |

| The Buddha, the Good Herdsman | 270 | |

| 184. | The Buddha, the Good Herdsman II | 270 |

| Chapter XIV. | Parables from the Medium-length Discourses on the Pleasures of Sense | |

| 185-191. | Seven Parables | 274 |

| 185. | Skeleton | 274 |

| 186. | Piece of meat | 275 |

| 187. | Torch of grass | 275 |

| 188. | Pit of red-hot coals | 275 |

| 189. | Dream | 276 |

| 190. | Borrowed goods | 276 |

| 191. | Fruit of tree | 276 |

| 192. | Fruit of tree | 276 |

| Chapter XV. | Parables from the Medium-length Discourses on the fruit of good and evil deeds | |

| Four Courses of Conduct | 280 | |

| Pain now and pain hereafter | 280 | |

| Pleasure now and pain hereafter | 280 | |

| Pain now and pleasure hereafter | 281 | |

| Pleasure now and pleasure hereafter | 281 | |

| 193. | Poisoned Calabash | 281 |

| 194. | Poisoned cup | 281 |

| 195. | Foul-tasting medicine | 282 |

| 196. | Curds and honey and ghee and jaggery | 282 |

| 197. | Even as the sun, so shines righteousness | 283 |

| Five Future States | 283 | |

| Hell | 283 | |

| 198. | Pit of red-hot coals | 284 |

| Animal kingdom | 285 | |

| 199. | Dung-pit | 285 |

| Region of the fathers | 285 | |

| 200. | Tree with scanty shade | 285 |

| World of men | 286 | |

| 201. | Tree with ample shade | 286 |

| Worlds of the Gods | 286 | |

| 202. | Palace | 286 |

| Nibbana | 287 | |

| 203. | Lotus-pond (cf. 169 and 179) | 287 |

| Chapter XVI. | Parables of the Sacred Heart of Buddha | |

| Thou alone, O my Heart, art called to be the Saviour of All | ||

| A. On the Treasury of Merits of Buddha | ||

| Thou art a Treasury of Merits ! | ||

| 204. | On the Perfecting of the Perfections Dhammapada Comm. | 289 |

| Mine eyes have I torn out! My heart's flesh have I uprooted ! | ||

| 205. | On the attainment of Enlightenment Dhammapada Comm. i. 8a | 289 |

| Blessed indeed is that mother, whose son is such a one as he ! | ||

| 206. | Abatement of plagues at Vesali Dhammapada Comm. Xx. 1 | 291 |

| If he but come hither, these plagues will subside | ||

| 207. | The king who took upon himself the sins and sufferings of his people Sanskrit-Chinese | 293 |

| If there be any that hunger, it is I that have made them hungry | ||

| B. On the Sacrifice of the Body and Blood | ||

| I will satisfy the hunger of my friends with my own body and blood ! | ||

| 208. | Boar and lion | 297 |

| Eat me, O lion ! | ||

| 209. | Fairy-prince and griffin | 298 |

| Eat me, O griffin ! | ||

| 210. | Jeweler, monk, and goose | 305 |

| I am ready to sacrifice my body to preserve the life of this goose ! | ||

| 211. | Rupavati | 313 |

| Only that I might attain Supreme Enlightenment ! | ||

| 212. | King Shibi and the bird | 314 |

| Thou alone, O my Heart, art called to be the Saviour of All | ||

| C. | On the Sacrifice of the Eyes | |

| Here is your eye! Take it! | ||

| 213. | King Sivi and the blind beggar | 324 |

| Should any man name my eyes, I will pluck them out and give them to him! | ||

| 214. | Subha of Jivaka's Mango Grove | |

| Here is your eye! take it! | ||

| A. Prose version | 325 | |

| B. Poetical version | 327 | |

| 215. | The prince-ascetic | 330 |

| Behold this, such as it is! Take it, if you like | ||

| 216. | Prince Kunala | 331 |

| Plucked out, the eye of flesh; but gained, the Eye of Knowledge! | ||

| 217. | St. Brigid of Kildare | |

| A. Medieval Latin version | 332 | |

| Dearer the Eye of the Soul than the eye of the body | ||

| B. Middle Irish version | 332 | |

| Lo, here for thee is thy beautiful eye! | ||

| 218. | St. Lucy of Syracuse | |

| A. Medieval Latin version (early) | 333 | |

| B. Medieval Latin version (late) | ||

| Philippus Bergomensis, De Claris Mulieribus | 333 | |

| Here hast thou what thou hast desired! Leave me in peace! | ||

| 219. | St. Lucy of Alexandria | |

| John Moschus, Leimon, Patrologia Graeca | 334 | |

| And seising here spindle, she bit, and gouged out here two eyes | ||

| 220. | King (Richard of England) and nun | |

| Jacques de Vitry, Exempla, 57 | 335 | |

| Behold the eyes that thou desirest! Take them, and leave me in peace! | ||

| Lost, the eyes of the flesh; but kept, the Eyes of the Spirit | ||

| Table of Parallels | 336 |