Count-Down From Solomon Or The Tamils Down The Ages Through their Literature- Set of Four Volumes (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAY969 |

| Author: | Hephzibah Jesudasan and G. John Samuel |

| Publisher: | Institute of Asian Studies, Chennai |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2004 |

| ISBN: | Vol:II- 818789203X Vol:III- 81878920013 Vol:IV- 8187892011 |

| Pages: | 1880 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 7.00 inch |

| Weight | 3.01 kg |

Book Description

Now a stigma was on me. And the higher education I went through did nothing to remove the stigma. I looked down on Tamil, with all my heart. My parents, took our Tamil connections very seriously, married me off-to a Tamil scholar! And on his part, one of my attractions was the reputation that had been building up for me, in my corner, as an English writer. Of course I was a stuck-up little writer, but that did not change matters. We were going to take our Tamil muracu (drum) and tom-tom it all over the world.

But, speaking seriously, there were two factors behind our common interest. One was the deep and unflagging faith that Miss. Morton, my teacher, then Principal of the Duthie School, had in my commission as English writer. Another was the passionate interest that Mr. C. Pannirukai Perumal, Head of the Department of Tamil, University College, Trivandrum, took in my husband's Tamil studies. Now a joint responsibility lay before us. The responsibility took on a clear outline after I had just completed my Grandma's Diary (poetry selections), to which Princess Gawri Lakshmi Bayi, of the Royal House of Travancore, had given the introduction. So, at the age of seventy-three, with a guru -in Centamil or "pure" Tamil he would be a formidable Kanakkayanar- aged seventy - eight, there rose before me a steep as-cent, like a road "stood on a hill".' I did not know ancient Tamil! We had, in 1961, got published A History of Tamil Literature together, my husband's being the 'mind moving behind it, and I being the scribe. Now conditions are so changed that, with my guru's help, and real old-world Tamil discussions with him (though without the accessory of a flag)2, the main responsibility devolves on me.

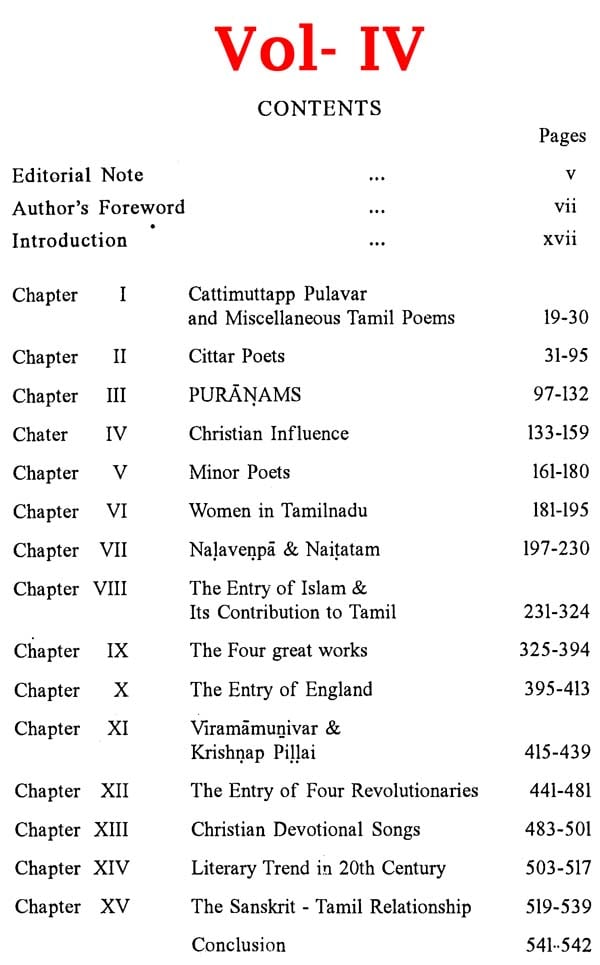

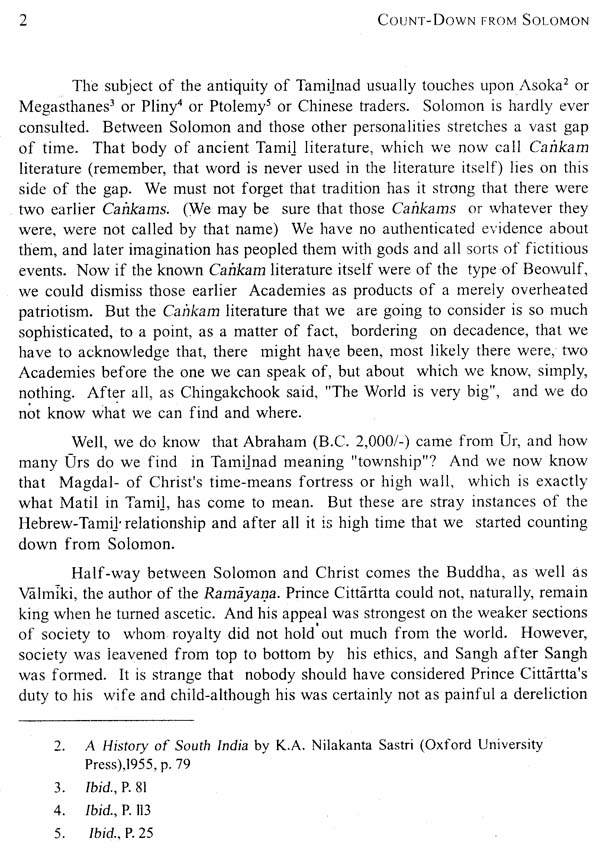

The present volume which is the first of a series of four volumes, deals with the pre-historic times when Solomon sent his ships to South India and the startling resemblances between words dating back to the times of Abraham or Christ are mentioned briefly before the Cankam Age itself is taken up. More than 2000 poems by 450 poets (included in the two volumes edited by Prof. S. Vaiyapuri Pillai) represent the Cankam Age (prior to 300 A.D.). But they are only remnants of an infinitely rich stock, a great part of which has been lost. One can deduce from them the dynastic line of more than four generations of Tamil princes (Cera, Cola and Pantiya). They tell a realistic story of a warlike people who divided their time between love and war, of the sufferings long sieges inflict, and of the anxious waiting of the lonely wife for the return of the warrior. They record the flora and fauna in the background, depict the simple pleasures of life, of the joy little children give, without whom "life has no meaning". They reflect Jain and Buddhist influences and the beginnings of the infiltration of Brahmanism. The technical perfection, the uniformity of tone, systematic division into Akam and Puram, and the subdivision of Akam into five Tinais according to a specific background and a specific pattern of behaviour etc. bespeak a highly developed, sophisticated school of poetry with its own strict code of rules regarding form, diction and imagery.

The bards are drawn from all classes. Many of them are sycophants praising their princely patrons in most extravagant terms. But there are exceptions like Kovur Kilar who tells the Cola king that he is "neither generous nor valorous" in closing the great gate of the fortress, whereby "infants cry for milk and cries for water are heard in the houses". Kings and queens also turn versifiers.

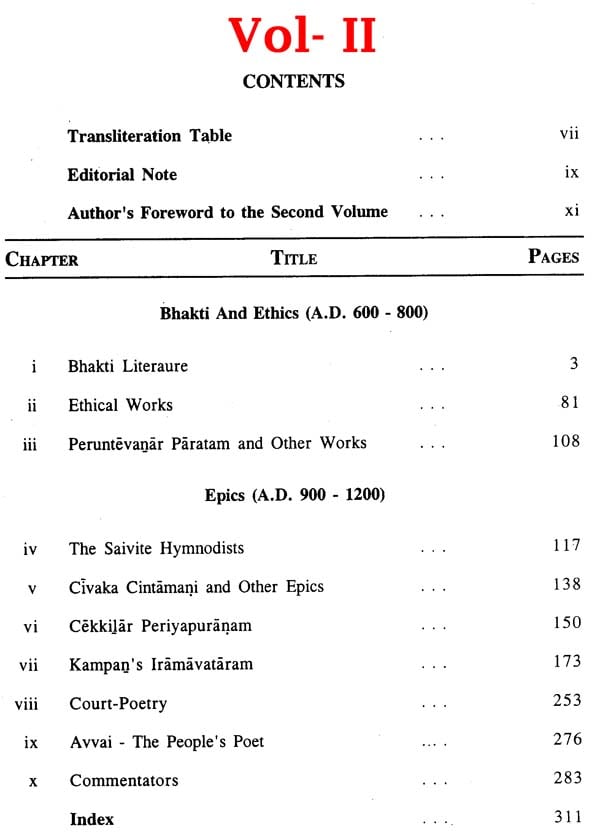

Vol. II is different. The writer is aware that religion is a very touchy affair. Diverse people find themselves in diverse religions for diverse reasons, and they cannot understand one another. Most formal religions develop a hard outer shell for protection, and any attempt to penetrate that is sure to be resented. Yet the literatures of all peoples have a great deal to do with their religious organisations, and one cannot ignore their social structure either, for society is sure to be knitted closely into the religious order of the people. Even communism is a religion of a sort, since, at its most passionate, it generates faith in certain ideals which it cannot allow to be broken. There is no society without a faith of some sort to hold it together.

Tamil literature from the seventh century to the twelfth reflects certain religious convulsions in Tamilnadu, which would have shaken its society at the roots. We can see all that faithfully recorded, not so much in the secular literary works as in the religious ones, as would be natural. But at this stage we can afford to look back dispassionately. The convulsions would be interesting, but we would not be involved in them. Hence it is that the writer of this book has had the courage needed to study them, along with my guide and guru*

The revelation of unexpected happenings is always exciting. It would have to be supported though, by the study of stone inscriptions and copper plates, given by royalty and individuals of importance, as authority for grants of land.

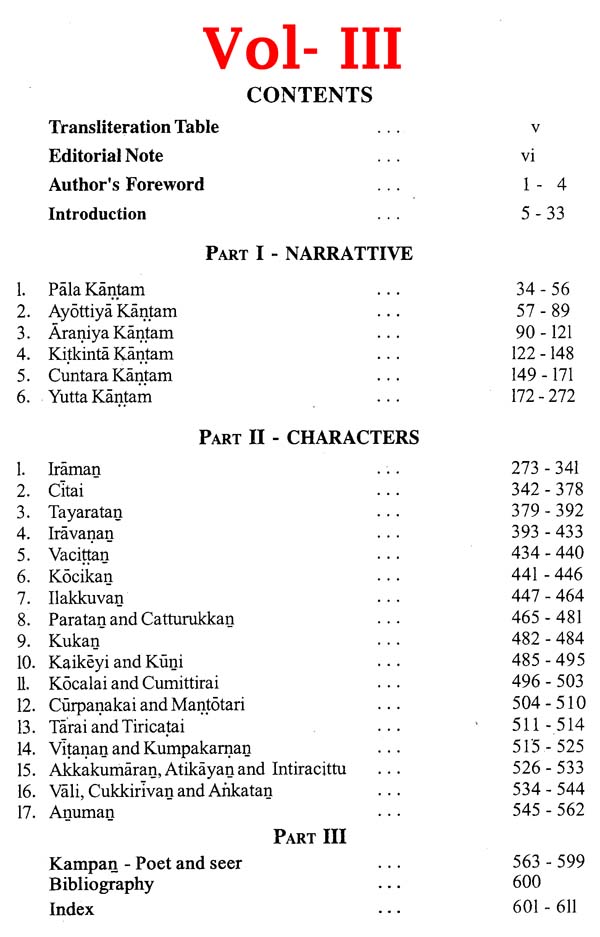

The passion to introduce him to the English knowing world was the automatic result. In the History of Tamil Literature, written by me in collaboration with my husband in 1961, it had been remarked that the urge with regard to Kampan was to mount to the roof tops and crow to the world, 'Come and see!' That urge has only been strengthened over the years. And so it was decided, when my husband and I planned this series together, of the vast ocean of Tamil literature, that Kampan should have one full volume, out of the four, to himself.

When I should say, we embarked on the study of Kampan, it was purely for the poetry of it. Stanza after stanza was passed on by an excited Teacher, mainly from memory, to an amazed pupil, not only across the Table, but on the road, in our daily walks together. And slowly, both of us discovered that there was more to it. We found that we could share a hearty laugh together, sometimes with Kampan, sometimes at him.

But, it was when I settled down to write, that I made the grand discovery that Kampan was not bound by religion or caste. That actually he belongs, not to Tamilnadu, nor to India, but to the whole of mankind. The necessity to speak about Kampan now took on the compulsion of a sacred duty.

Actually, the greatest injury that could be done to Kampan's name is to call his work the Kamparamayanam. He did not do it. Once you call it the Ramayanam, away will run the D.M.K.s (along with the D.K.s!) a sizeable portion of the Tamil, population, not caring, not daring, to take a look back. They had wanted to consign it to the flames! The Brahminists, a very influential portion of the Tamil population, might permit it within their campus, though sometimes with a slight sneer, at what is "only" the translation of Valmiki. But between these two groups lie the great masses of the Tamils and they are, normally, guided by one or the other of these groups.

I have been privileged as few women have. I have to account for my privileges. As a daughter, with both parents passionately interested in my English education, and especially a Teacher-father whose strange dream was to see me an English poet. As a wife, with a Teacher-husband, struggling in the toils of a great and ancient literature, which he only longed to be made articulate in English, as the international or universal language. As a mother, with children who know the value of the responsibility devolving on me.

But, I have had other Teachers. There was a little, dark, frail, elderly, turban'd, Primary School Teacher of mine, in Katha, Burma,-now, Myanmar. I remember him, Saya U Pe, trudging all the way from his home to mine, on the eve of my leaving Burma after a two-year schooling, to present me with a book to keep. The book-I have it still-is on the Making of a Home. A blessing, from a Teacher, on the future home of a little girl not yet in her teens.

I remember my dear Miss. Edwin, so much involved in me at boarding-school in Nagercoil, who introduced me to the Principal of the school, Miss. Olive Morton, who was later to write to me, from Sheffield, "I have often thought of you as my child," and who is one of the two Teachers to whom this work is dedicated. My teachers-there are several others, including Dr. A. Sivarama Subramaniya Aiyar, at College level-are standing behind me, - an avenue of them-showing the way ahead. The Teacher-student relationship is what has built up my inner life from childhood.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages