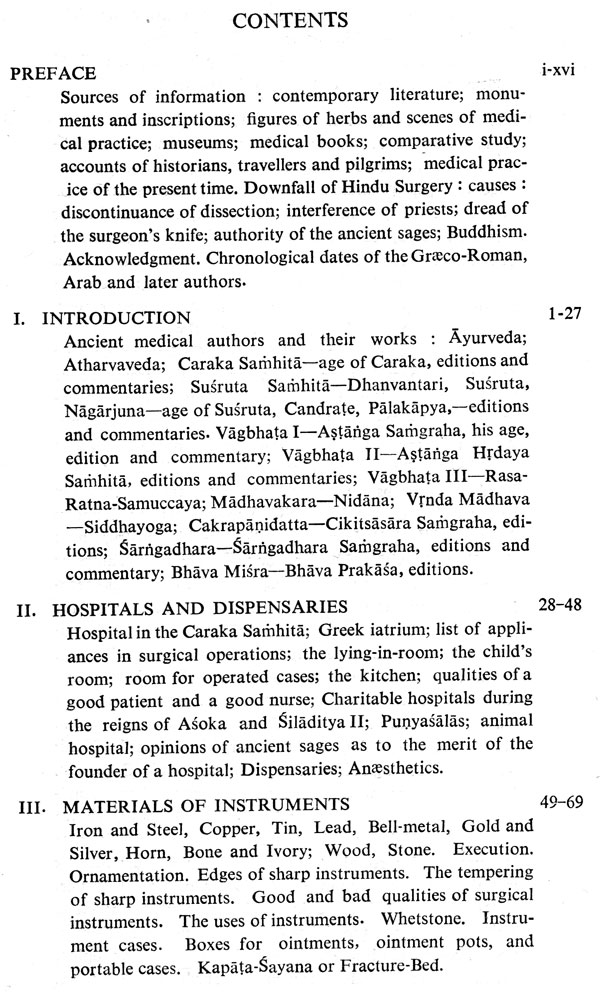

The Surgical Instruments of The Hindus (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAR368 |

| Author: | Girindranath Mukhopadhyaya |

| Publisher: | Meharchand Lakshmandas Publications |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1987 |

| Pages: | 423 (82 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 570 gm |

Book Description

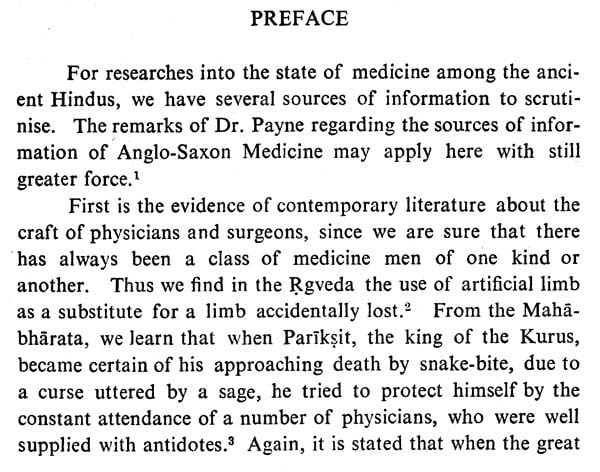

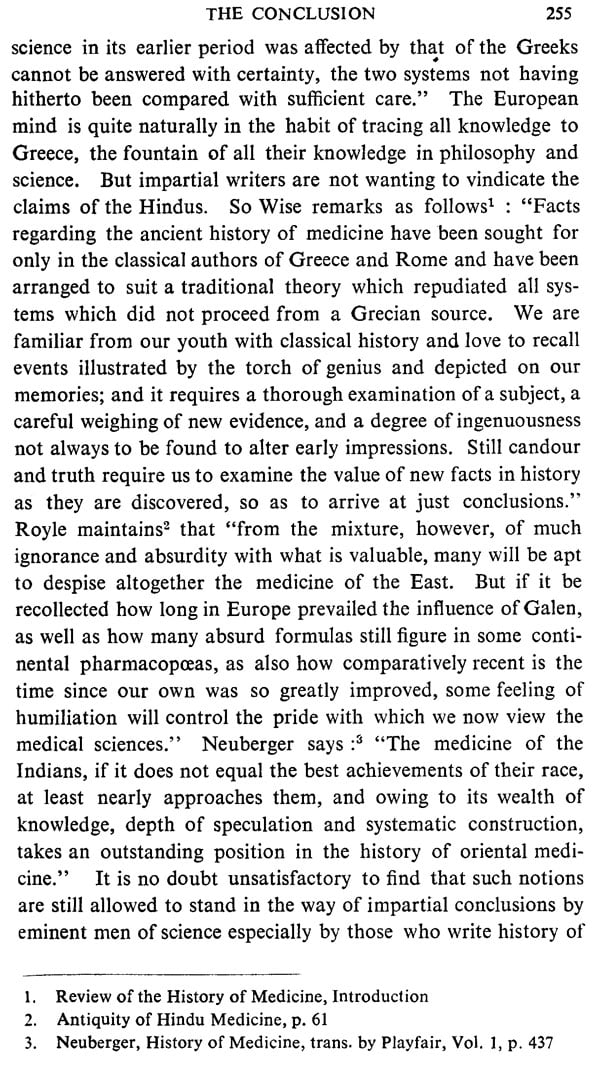

For researches into the state of medicine among the ancient Hindus, we have several sources of information to scrutinise. The remarks of Dr. Payne regarding the sources of information of Anglo-Saxon Medicine may apply here with still greater force.

First is the evidence of contemporary literature about the craft of physicians and surgeons, since we are sure that there has always been a class of medicine men of one kind or another. Thus we find in the Rgveda the use of artificial limb as a substitute for a limb accidentally lost. From the Mahabharata, we learn that when Pariksit, the king of the Kurus, became certain of his approaching death by snake-bite, due to a curse uttered by a sage, he tried to protect himself by the constant attendance of a number of physicians, who were well supplied with antidotes. Again, it is stated that when the great warrior Bhisma was wounded in war, the skilful army surgeons came to him with the necessary medical and surgical appliances to treat his wounds. From the Mahavagga, we team that Jivaka, the personal physician of Buddha, practised cranial surgery with success. In the Malavikagnimitra, we find the use of charms-a signet ring as a healing talisman for the cure of snake-bite; and also we find there a reference to a class of physicians who specialised themselves in Toxicology (Visa-vaidya) and were held in high esteem for their professional skill by the public.' From the Bhojaprabandha, the administration of some kind of anaesthetic by inhalation before surgical operations can be ascertained. Similarly from the books of Law, we know the relations of the profession to society in general. In the Manusamhita, we have unmistakable testimony of the decline of Hindu surgery as the author prohibits the eating of cooked rice from the hands of a surgeon.

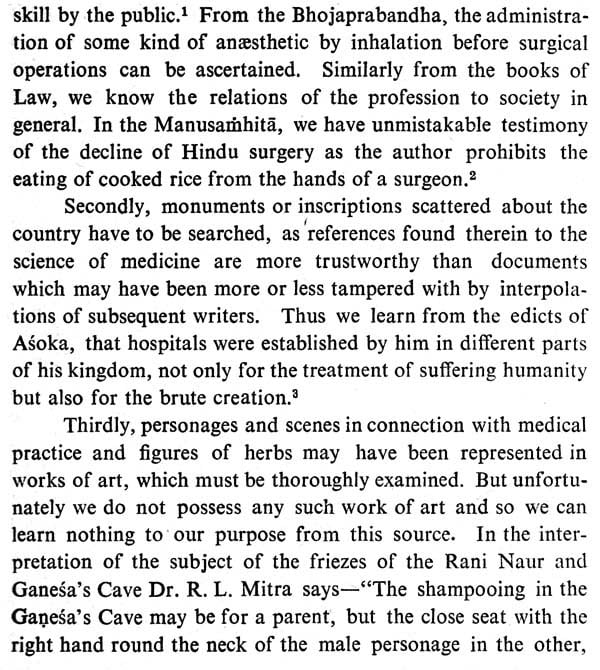

Secondly, monuments or inscriptions scattered about the country have to be searched, as 'references found therein to the science of medicine are more trustworthy than documents which may have been more or less tampered with by interpolations of subsequent writers. Thus we learn from the edicts of Asoka, that hospitals were established by him in different parts of his kingdom, not only for the treatment of suffering humanity but also for the brute creation.

Thirdly, personages and scenes in connection with medical practice and figures of herbs may have been represented in works of art, which must be thoroughly examined. But unfortunately we do not possess any such work of art and so we can learn nothing to our purpose from this source. In the interpretation of the subject of the friezes of the Rani Naur and Ganesa's Cave Dr. R. L. Mitra says-"The shampooing in the Ganesa's Cave may be for a parent, but the close seat with the right hand round the neck of the male personage in the other, would be highly unbecoming in an unmarried female. But if the stooping figure be taken to be that Of a wounded man, a wounded priest for instance, the lady may be a maiden nursing him without any offence to propriety. It is true, the appearance of the figure on the mattress does not indicate suffering from a wound, but in the Rani Naur frieze, the stooping head affords some indication of it."

Fourthly, the various kinds of surgical instruments preserved in museums are to be examined and the reports of finds of surgical appliances in various localities are to be studied. We know what a flood of light has been thrown on ancient Greek surgery by the steady progress of archaeological discovery and finds of instruments at Pompeii, Herculaneum and elsewhere, and by the study of the specimens preserved in the Naples museum, the Athens museum and other museums of Europe. But as far as I have been able to trace, our museums contain no finds supplying us with any information on the subject.

Fifthly, the literature of medicine itself should be thoroughly inquired into and excerpts elucidative of our subject should be compared with one another. "The detailed descriptions of the very numerous Hindu instruments not being very minute or precise, Professor Wilson says, we can only conjecture what they may have been, from a consideration of the purport of their names, and the objects to which they were applied, in connection with the imperfect description given." We are fortunate, however, in possessing a copious medical literature of great merit from very early times.' We shall describe the important books in the introductory chapter, with short notices of their authors.

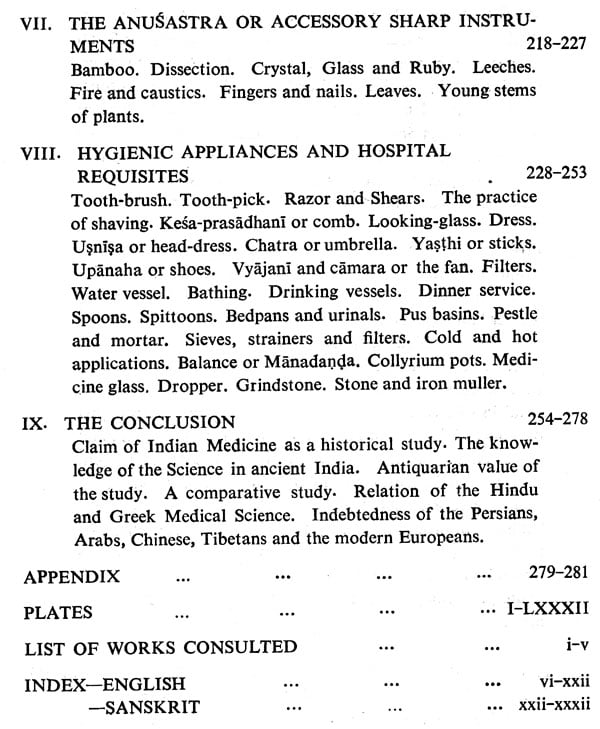

**Contents and Sample Pages**