Vasantotsava: The Spring Festivals of India Text and Traditions

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDD092 |

| Author: | Leona M. Anderson |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2005 |

| ISBN: | 8124600112 |

| Pages: | 254 (11 Color Plates) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.8" X 5.8" |

| Weight | 610 gm |

Book Description

From the Jacket

This study treats Vasantotsava as a thematically unified "generic" whole embracing a wide range of spring festivals including the Phalgunotsava, Caitrotsava, Phalgu, Madhutsava, Madana-mahotsava, Madanatroydasi, Anangotsava, Madanadvadasi, Kamotsava, Sripancami, Yatra-mohotsava, and Holaka (Holi). These festivals are pansectarian in character and incorporate a variety of ritual observances practised throughout the Indian subcontinent.

Signifying the termination of winter and announcing the advent of spring, the celebration was a diverse and complex spectacle situated within the framework of Indian ritual and myth. On the basis of Puranic and ritual text, folk tales, drama, poetry, and narratives in mixed prose and poetry (campus), Dr. Anderson addresses complex issues of indigenous ritual, mythology and tradition. The vasantotsava incorporates a broad spectrum of human concerns: in the sphere of polity, it can be turned to account of celebrate and reinforce the power of the king; in the social sphere, it is a time of revelry and merry-making indicative of the annual renewal in human affairs; and in the sphere of religion, it celebrates the exploits of the gods and establishes a link between human and divine actions and events.

The festive season is marked by drinking, dancing, and powder throwing, by revelry and amorous passion, by fecundity and regeneration. Dr. Anderson re-assesses Sanskrit texts from the ancient and medieval periods, namely, the Ratnavali, the Kathasaritsagara, the Vikramacarita, the Bhavisya Purana, and the Virupaksavasantotsava-campu. Each text is distinctive in its portrayal of spring festivals, outlining either the role of kings, deities invoked and worshiped, rituals enacted and myths recounted (especially those of Kama, the god of love/desire, and those of the goddess Holaka).

Explored here, then, are the component elements of the Vasantotsava: rituals, symbols and underlying motifs. Given the continuing importance of spring festivals in the Indian religious calendar, this study aims to contextualize as well as particularize their practice.

About the Author

Leona M. Anderson was trained at McMaster University, Canada and currently teaches Hinduism at the University of Regina, Canada. She has resided in both Pune and Delhi and has on several occasions been affiliated with the Deccan College, Pune. She has received grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Her articles have appeared in many journals and she has participated at symposia worldwide. Her current research centres on a study of the Festival of Lord Ganapati.

Introduction

The Indian Spring Festival, the Vasantotsava, is one of the multitude of celebrations which punctuates the ancient and medieval festival calendars. It is observed in the vernal season, in the interstices between winter and spring, sometimes signifying the departure of winter, at other times announcing the advent of spring. Most often, however, in anticipation of regeneration and rebirth, it plays upon the potential inherent in the hiatus between these two seasons. Although the Vasantotsava is not celebrated in contemporary India in its original form, literary evidence culled from Sanskrit texts belonging to the pre-modern period suggests that the Vasantotsava, in times past, was a signal event pivotally positioned within the Indian religious years.

A body of pertinent texts attests to the variability, complexity and multiplicity of the ritual and mythological framework of the Spring Festival as it was particularized in ancient and medieval India. Though our accounts by no means exhaust descriptions of the celebrations, they are distinct and plentiful, enriching our knowledge of the manner in which the spring season was perceived and practiced in medieval times. The two-fold purpose of this study of the Vasantotsava is first, on the basis of accounts in Sanskrit literature, to arrive at a description of the structures and forms through which the festival was celebrated and second, to shed some analytical light upon the panorama of ritual actions portrayed in these diverse sources.

My primary source material is drawn from a broad range of Sanskrit literature, including puranas, ritual texts, folk tales, drama, poetry and narratives in mixed prose and poetry (campus). Five principle texts, the Ratnavali, the Kathasaritsagara, the Vikramacarita, the Bhavisya Purana (Ch. 132, 135) and the Virupaksavasantotsavacampu, have been selected here in pursuit of a fuller picture of the Vasantotsava.

Composed in Sanskrit in the seventh century AD, the Ratnavali of Sri Harsa is significant to our study on two counts: first, it was written specifically to be performed on the occasion of the Vasantotsava and second, it contains several detailed albeit sporadically positioned accounts of the constitutive format of the celebrations. The Spring Festival depicted herein spans a period of at least three days and is set in two separate locations. There are in the Ratnavali, two spatially distinct forums for spring ceremonies: one focusing on the festival as it was played in the city streets and a second focusing upon the celebrations in the garden. In each of these settings, the Vasantotsava takes on distinctive characteristics: in the urban environment the celebrations are characterized by the free and sometimes wild behavior of the citizens, while, in the garden, the attention is centered on the private worship of the deity Kamadeva, the Hindu god of desire and love. Insofar as the Ratnavali was written to be performed on the occasion of the Vasantotsava, we may well assume that this play itself had some importance in the celebration of the festival. Plays of this type seem to have been commonly enacted on this occasion. The Ratnavali, then, is of special interest as it gives us a relatively complete picture of this festival as celebrated in the seventh century AD in the central Indian city of Kausambi, thus affording us an understanding of the transitional development and regional variation of the festival with some degree of temporal and geographic precision.

Further descriptions are drawn from the Kathasarit-sagara and the Vikramacarita. Both are collections of stories recorded in north India during the eleventh century AD. Although the Kathasaritsagara is a relatively late compilation, the stories therein date to very early times. The Vikramacarita is a collection of thirty-two tales in praise of Vikramaditya which are alleged to have been discovered by Bhoja of Dhara in the eleventh century AD. Most probably they were written for him or under his auspices. Probably they were written for him or under his auspices. These texts provide us with data concerning popular rites which were not necessarily codified in puranic or ritual literature. The descriptions of the Vasantotsava in both the Kathasaritsagara and the Vikramacarita are typical in that their brief vignettes of the Spring Festival function as miseen-scene. They are significant for our discussion as well, for they both tend to highlight the role played by royalty in the celebration.

Two chapters from the Bhavisya Purana amplify our picture of the Vasantotsava through the re-telling of myths germane to this festival celebrations. Here specific links between the Vasantotsava and the tradition of Hindu mythology are established and authenticated. My discussion centres on the role of mythological figures such as Kama, Siva and the raksasi Dhaundha, the central role played by children in the celebrations, and an analysis of the activities which make up the festival, such as lighting and circumambulating a bonfire. Like all puranas, the Bhavisya Purana is difficult to date and like all puranas it clearly preserves popular, perhaps non-Sanskritic rituals, but in a form filtered through the Sanskrit language and culture. Although the puranas contain copious idiosyn-cratic material, they do give us information regarding orthodox ritual action which often comprises the basis of orthodox ritual manuals (Nibandhas).

Finally, the Virupaksavasantotsavacampu, a text in prose and verse dating from the fifteenth century AD has, as its principal subject, the documentation of the Vasantotsava as practiced during the Vijayanagara period of Indian history. Location-specific, the Campu provides a different perspective on the festival: it is here described primarily as a Saiva temple festival revolving around the deeds of Virupaksa (Siva) and his consort Pampa (Parvati). Simultaneously, however, it validates the king of Vijayanagara, the capital of his kingdom, and his sovereignty over this realm.

Occasionally the information in these five primary texts is only briefly sketched and we must turn to other supplementary Sanskrit sources to flesh out our portrait of the Vasantotsava. The wealth of extant alternate representations of this festival, for the most part containing brief descriptions of it, have not been included in full primarily due to the brevity of their descriptions. They are, however, large in umber and their significance lies in that they either confirm or contradict the information contained in our more complete textual sources. Ritual texts including, for example, the Grhya Sutras, Srauta Sutras, and Nibandhas enumerate the figures to be worshipped, the rituals to be performed, an, specifically, how they are to be performed. These sources are repositories of pertinent information regarding rituals and procedures which are, or ought to be, undertaken by individuals and groups of individuals either to gain merit or to fulfill a particular social obligation. These materials also contain significant data with respect to the mythological context in which the festival is set. So, for example, we learn of the exploits of various deities of the Hindu pantheon and their particular roles in the context of these celebrations. In short, our five primary texts coupled with these explanatory ritual texts reveal the panoply of vernal celebrations described and prescribed by the Sanskrit literati of the Hindu tradition. In formalizing our understanding of the festivities, we shall rely on these five primary texts as guides.

We can glean from these Sanskrit portrayals of the Spring Festival information which delineates the festivities within the parameters of a particularized and ritually circumscribed environment exclusive to a select elite and also information regarding the celebration of spring that is more generalized, more popular, in which a majority of individuals from all sectors of society is engaged. Each text formulates the festival in accordance with its own frame of reference. Each portrayal of the celebrations is, indeed, a portrayal, a stylized vision filtered through the media of the text. Just as each festival is celebrated in a particular way at a particular times, so too, each of our descriptions is unique to a specific author, time, and place. Just as the rites and myths of which this festival is composed are negotiated or renegotiated in every celebration, so too, are they recast in every textual description. The sketch generated from these specific and general source materials becomes more sharply delineated by analyzing the various elements of which this festival is composed, the manner in which they combine and re-combine, as well as by examining some of the major themes which the festival embodies. When examined in toto, this body of Sanskrit texts Vasantotsava than any single text. The vigourous and colourful modern Spring Festival is one of the few spring festivals described in both ancient and medieval texts to survive into modern times. Since this is the case, our analysis may provide some background through which the modern Spring Festival may be more readily understood.

| vii | ||

| Acknowledgements | vii | |

| List of Plates | xi | |

| 1 | Introduction | 1 |

| 2 | Vasantotsava and its Variants | 11 |

| 3 | Ratnavali: the City | 29 |

| 4 | Ratnavali: the Pleasure-Grove | 49 |

| 5 | The Spring Stage | 77 |

| 6 | The Kathasaritsagara | 95 |

| 7 | The Vikramacarita | 111 |

| 8 | The Bhavisya Purana: 135 - Kama | 121 |

| 9 | The Bhavisya Purana: 132 The Demoness | 147 |

| 10 | The Virupaksavasantotsavacampu | 171 |

| 11 | Conclusion | 199 |

| Glossary | 215 | |

| Dates of Texts | 225 | |

| Bibliography | 229 | |

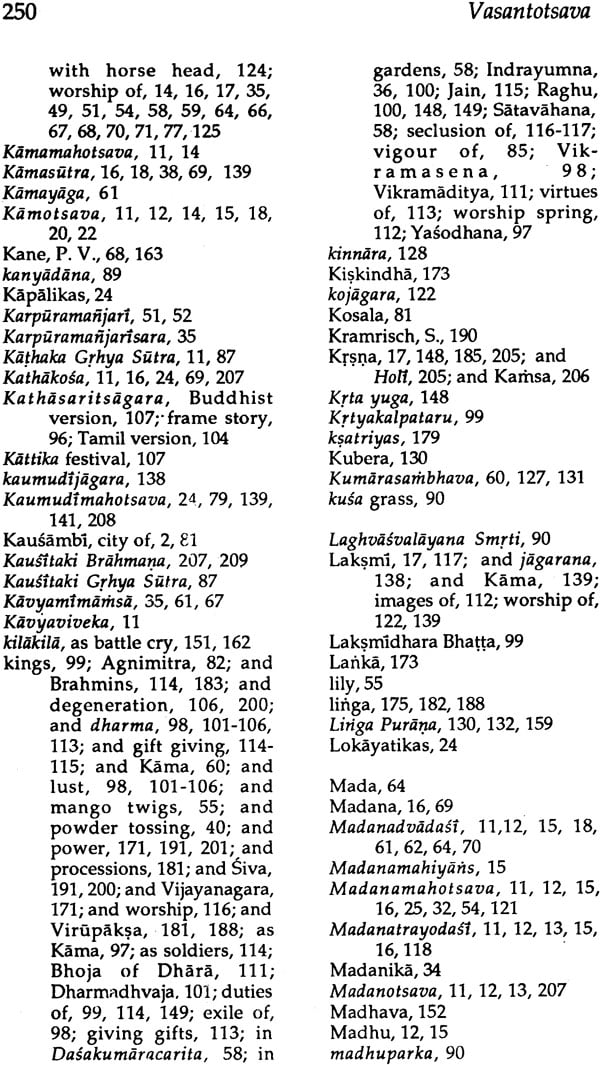

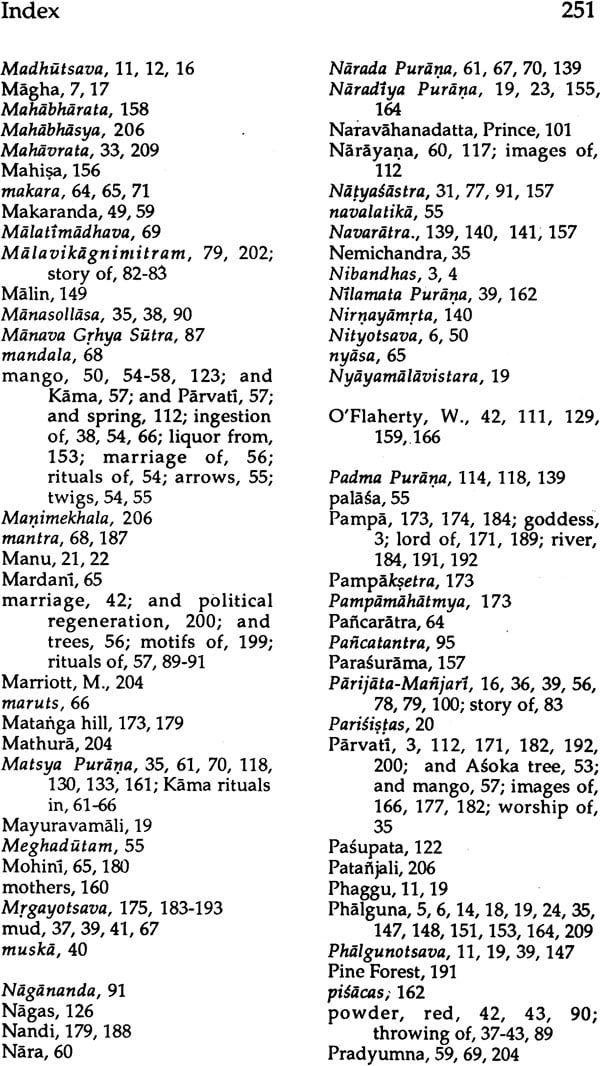

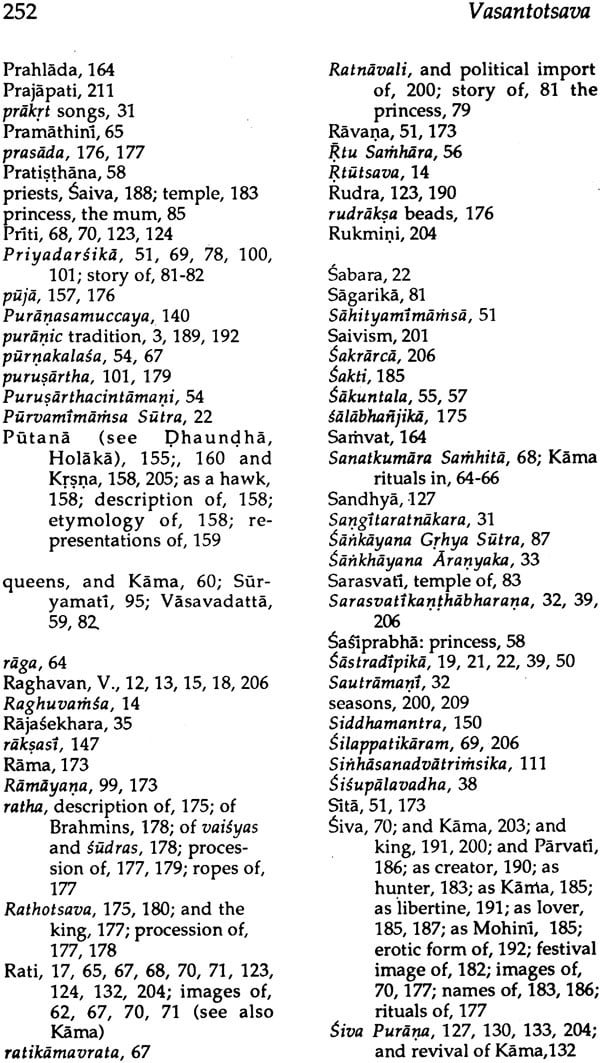

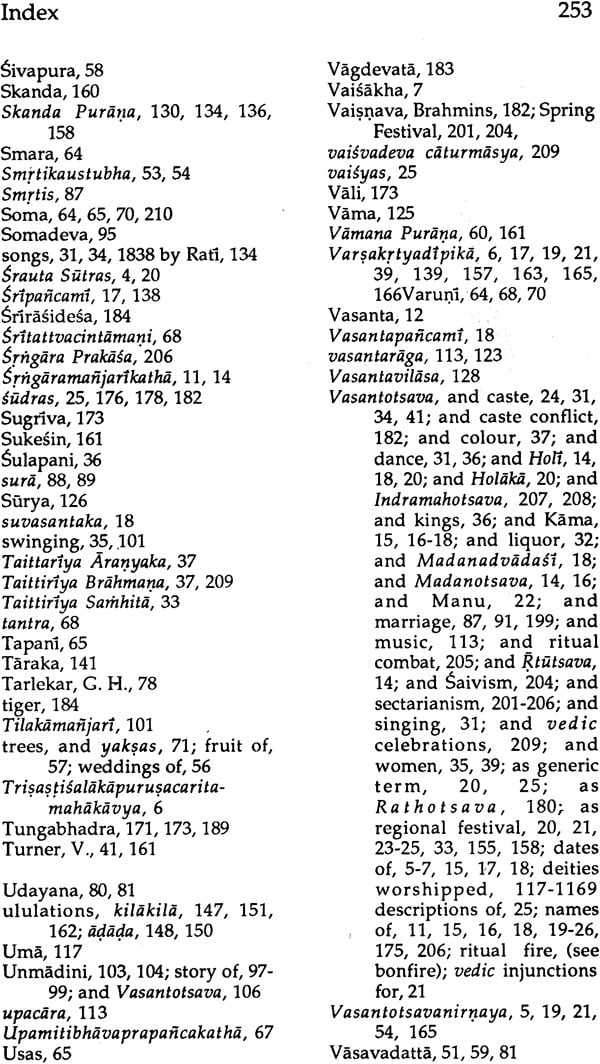

| Index | 247 |