Vyapar Shastra (The Practice of Business in India)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAP432 |

| Author: | Vishal Shivhare |

| Publisher: | Jaico Publishing House |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2017 |

| ISBN: | 9788184958980 |

| Pages: | 208 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.0 inch X 5.0 inch |

| Weight | 190 gm |

Book Description

Vyapar Shastra gives an engaging account of the history of Vyapar, or business, in India. From the local kiranawalla to urban businessmen heading conglomerates, it details the lives of vyaparis across the social spectrum and how they drive India's economy.

Filled with captivating illustrations, the text covers a range of business models — from the mela to the mall; from the village haat to the hypermarket; and from the trusted city bazaars to novel e-commerce setups.

In two distinctive book sections—Vyapar and Parivar—the author reveals the characteristics of family businesses in India and how the two often merge in the Indian social context. Enriched with personal encounters—starting from shawl merchants in Kashmir to tea-stall owners in southern India—and his observations of the emerging startup models, this book examines the highs and lows of vyapar in a changing world.

India is widely known for her culture, diversity, language, spiritual traditions and alternative practices throughout the world. But there is one other field where her contribution is seldom spoken about - trade and commerce. The role of Indian merchants has been downplayed so far by the West and paid no heed to by her own citizens. But one has to only look around to see the huge number of businessmen and the many kinds of trades going on in India to debunk this impression.

Myth has it that India was once hailed as the land of astonishing wealth and beauty, and countless travelling writers referred to it as the 'Golden Sparrow' or 'Sone hi Chidiya'in their chronicles. As a child, I used to wonder if it was a real bird. If it was really made of gold; if so, how could it defy gravity and fly? How big was this bird? However, as I grew up, I realized it was an honorary title conferred by the travelers. Unlike names that serve the purpose of identification, titles are conferred out of respect and admiration. From 300 BC to AD 1600, we find the title 'Sone hi Chidiya' popping up in many chronicles of writers and explorers like I-Tsing, Fa Hian, Huang Ho, Ibn Batuta, Al-Baruni and Marco Polo. Although India as a country has had many different names over several hundred years - Aryavarta, Hindukush, Sindhustan, Bharatvarsha, Jambudwipa, Gangaridai, Nabhivarsha, Tianzu, Hindustan and Bharat - but it has always held the single title, 'Sone hi Chidiya'.

Even before Christ was born, bullion was coming to India from all over the world. In AD 77, the Roman historian Pliny the Elder called India 'the sink of the world's precious metal' in his encyclopedic work Naturalis Historia. Pliny mentions that the Roman Senators were annoyed and distraught by their women who imported huge amounts of spices and luxurious cloth from India, draining the Roman wealth.

Between the rule of several dynasties and monarchs, India was subject to countless invasions. When Nadir Shah of Persia invaded India in 1739, his departing caravan of plundered wealth and booty is estimated to have stretched for 150 miles. Such was the plunder that Shah suspended all kinds of taxation in Persia for three years.

But no matter how many times the raiders plundered the wealth and gold of the country, it would be replenished in no time. With no active gold or diamond mines, it was the Indian merchants or vyaparis who replenished the wealth by bringing back the gold. Not by force, but by their seafaring and mercantile spirit. Just like a bird goes far in search of food and returns with its beak full, Indian vyaparis, too, would go far and wide and return with their ships full of gold and silver. In fact, as recounted by historians, the hulls of these returning ships would be half submerged in water because of the weight of the gold they carried.

In their book Why Nations Fail, authors Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson describe how, from AD 1 to AD 1000, India's share of the global economy was over 35 per cent. For a large part of history, India remained the trade and culture capital of the world. According to economic historian, Angus Maddison (Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD), India, despite the invasions and plunders by various raiders, had the world's largest economy between AD 1 and AD 1000.

Contents

| Prologue | xi | |

| PART I: VYAPAR | 1 | |

| 1 | Origins of Vyapar | 3 |

| 2 | Constituents of Vyapar | 16 |

| 3 | India: A Nation of Vyaparis | 27 |

| 4 | Passion, Profession or Religion? | 39 |

| 5 | Vyapari: More than a CEO | 49 |

| 6 | Accidental Altruists | 62 |

| 7 | Dealing with Loss | 68 |

| PART II: PARIVAR | ||

| Introduction | 85 | |

| 8 | Vyapar and Parivar | 89 |

| 9 | Individual to Institution | 112 |

| 10 | Features of Family Business | 120 |

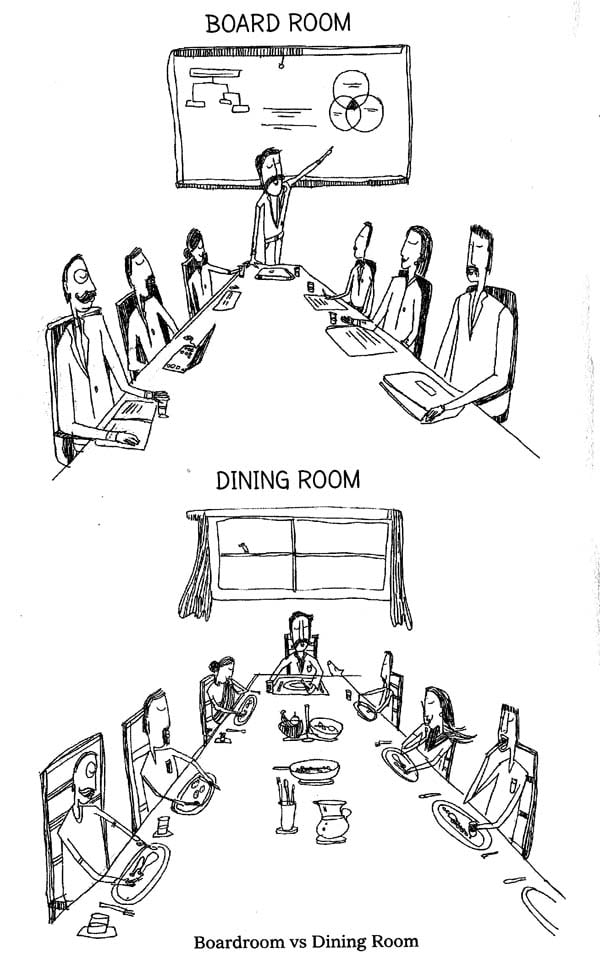

| 11 | Boardroom vs Dining Room | 131 |

| 12 | Dad-Boss-Dad | 139 |

| 13 | Succession or Inheritance | 150 |

| 14 | Vyapari: Omnipresent Leader | 161 |

| 15 | Startups: The New Vyapar | 174 |

| Acknowledgements | 193 |