Classical Dances and Costumes of India

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAK548 |

| Author: | Kay Ambrose |

| Publisher: | MUNSHIRAM MANOHARLAL PUBLISHERS PVT LTD |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9788121512428 |

| Pages: | 102 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.5 inch x 9.0 inch |

| Weight | 580 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

The Classical Dance and Costumes of India by Kay Ambrose steers clear of the twin evils of writing :the learned writing for the learned and the dilettante writing for others of his class. It treats the four classical school of Indian dance- Bharata Natyam, Kathakali, Kathak and Manipuri-with understandin and objectivity. The reader is provided with a sketch of Indian mythology and music before he is exposed to the dance proper which are presented in such a manner that none will experience any difficulty in learning the divine and mundane aspects of these schools of dance. The chapter on the costumes of India gives not only idea of the correct costumes of the particular schools of dance but also of the endless variety and rich colour of Indian costumes. In addition to classical dances, the reader is given a taste of Indian folk dance and dances of Ceylon.

The technical sketches more than supplement the text. The reader will not only by able to understand the various dance styles but recognize them while witnessing public performance. A few, if they try hard , may be able even to demonstrate authentic dance style.

Clarity and economy of expression couple with accuracy of illustration are the hallmark of this book which no dance lover should miss.

About the Author

Kay Ambrose was author artist and designer. She studied fine arts at Reading University from 1933 to 1936 and again in 1943-44 where she won awads in drama elocution and dance. She made her first mark in the world of dance as an author and illustrator of many books on dance. In 1938 she illustrated Arnold L. Haskell’s book Ballet. In a span of about twelve years she wrote several books, many of which became collector’s items.

She travelled with Ram Gopal and his Indian dance company as art-director, lecturer and dancer, after which she wrote the still definitive Classical Dance and Costumes of India in 1950.

She accepted a position as artistic director in National Ballet Company of Canada in 1952 designing around thirty productions for the company. After 1961-62 season Ambrose took a sabbatical from which she never returned. Upon hearing of her untimely death Celia Franca cabled to her surviving relative: “Ballet world has lost one of its most talented and best loved artists.”

Introduction

I met Kay Ambrose in 1939 during my first visit to London's theatreland. Miss Ambrose was at the beginning of her career as an author and artist of dancing, and particularly Russian ballet, and was preparing her first work with Arnold Haskell, and she came back-stage at the Aldwych Theatre to make sketches of my performance and gather information for her book, and thus we met.

I answered Miss Ambrose's questions as simply as I could and we soon became good friends. I told her she ought to study the Indian dance with a view to preparing a book on the subject, as she seemed to catch movement with ease and accuracy. On my next visit to London less than a year later, the Vaudeville Theatre in 1940, there was Miss Ambrose with an enormous sketch-book and quantities of pencils, energy and determination to learn all she could. She watched me practise, attacked all Indian subject-matter including our music, and accompanied my little group and myself during our small tour of England immediately after our stay in London. Then the war-clouds which had been gathering burst, my musicians grew anxious and I had to return to India. Miss Ambrose sent me a copy of the Balletomane's Sketchbook, her book with Haskell, and the critiques which said that the drawings of Indian dancing were the best. Here is a letter I wrote to her in 1942.

Your letter reached me safely and I am glad you got my parcel of books. If you absorb them thoroughly, and continue to refresh your memory of the Indian dance in the way I suggested, by visiting the British Museum's stock of sculptures and paintings, you'll find that later on when you can visit India you will under- stand the Indian dance far more readily. And keep your eyes open in London- you'll be surprised how many junk-shops have real treasures of Indian art in them, brought over by English people who learned to love and understand our Indian expression of beauty. (I don't mean you to h'9 them, only to look at them!)

I often think of the ballets I saw in Europe and the lovely long, straight lines of the dancers. Carry on with your studies of the ballet and do lots of books. I know that ballet is in its infancy compared with our ancient dances over here, but it's a lusty infant and by far the best medium of dancing I saw in the West, and there is no doubt that whereas our dancers could teach yours a good deal, yet in India we have everything to learn from you concerning organisation and stage presentation. I have a strong feeling that through ballet, dancing is going to become a part of everyday life in the West as well as the East-and I bet you A. L. H. will have a good deal to do with that transformation; he was telling me his ideas of a National ballet in England when we met in Bournemouth, and I told him we should have something on the same lines over here in India.

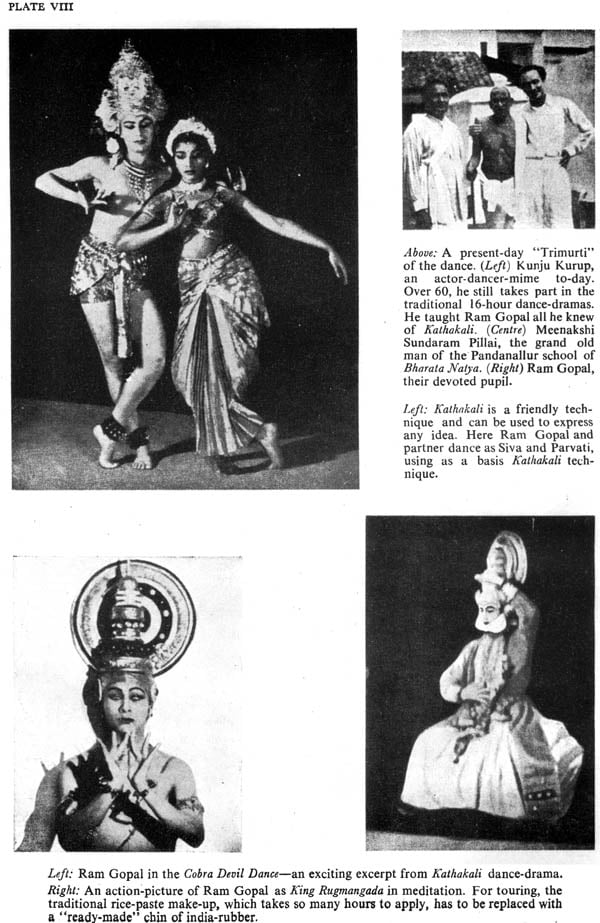

You remember I told you the story of "Bharata Natya," the ancient dance of the bayaderes that I'm sure Pavlova was seeking and never found because every- one in India told her that it had died -out? And I showed you some of the movements? Well, I am going to put in some really high-pressure work with Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai. Krishna Iyer, the greatest critic and writer of B. Natya over here, says that some of the dances and movements can be best performed by men, and Meenakshi S. is the greatest teacher of all in the vigorous style. So Krishna Iyer and I are going to Tanjore together soon and I'm going to work like mad, live in a hut and dance till I drop on Meenakshi S.'s mud classroom floor, until he says I am perfectly trained. If only those ballet-dancers of yours could see our classrooms in India, how they would appreciate their mirrors, bars and nice level wooden floors!

As soon as possible I will come back to England and bring a real company with me this time. You'll be able to join my tours and then come to India with me, and see for yourself the things I've described to you, done my best to show you and told you how to read up and study on your own. I always make my dancers study the dance as well as practise it, and you as a writer and artist should study far, far more than they do.

So you work hard and I'll work hard, and we'll see what we can' do about this book between us. But you MUST see the dance in its proper setting here in India first. Just you wait till you see Balasaraswathi-I'll ask her to dance specially for you. I have the instinct that this poor old world is going to need all the spiritual consolation the real Indian dance can give, and the sooner the better.

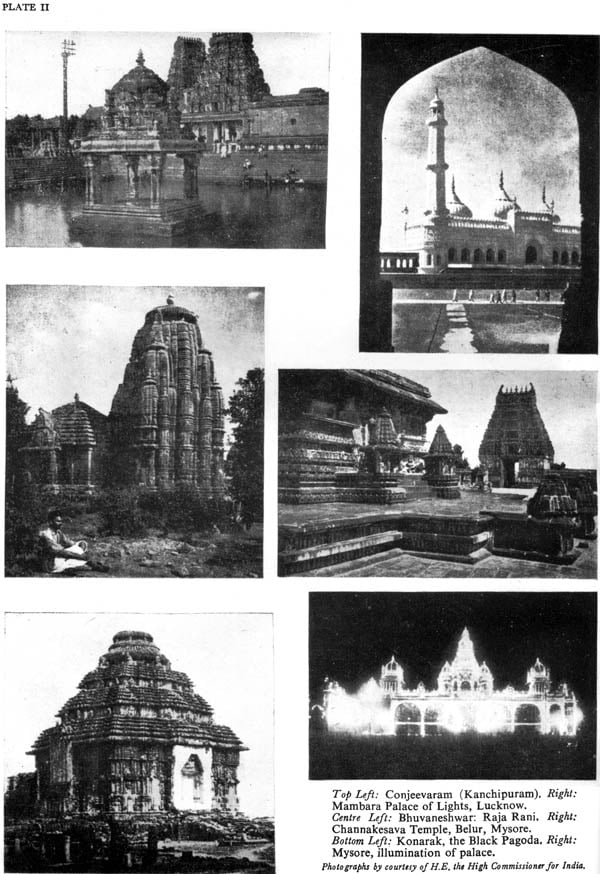

Incidentally I enclose a taste of what you'll see one day soon-some photos of my recent performance in Belur Temple in Mysore State. The floor was specially made for dancing, and the last person to dance on it did so nearly 2,000 years ago ....

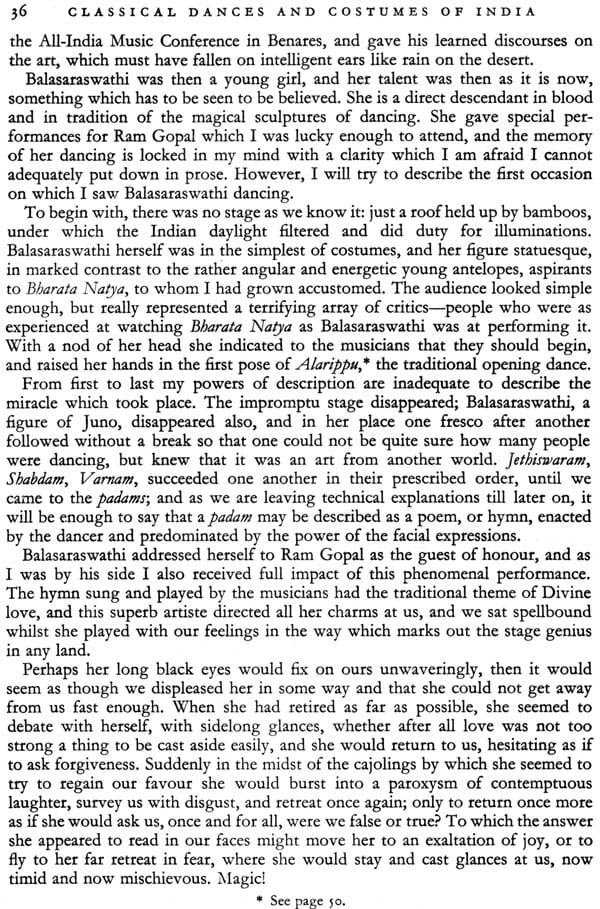

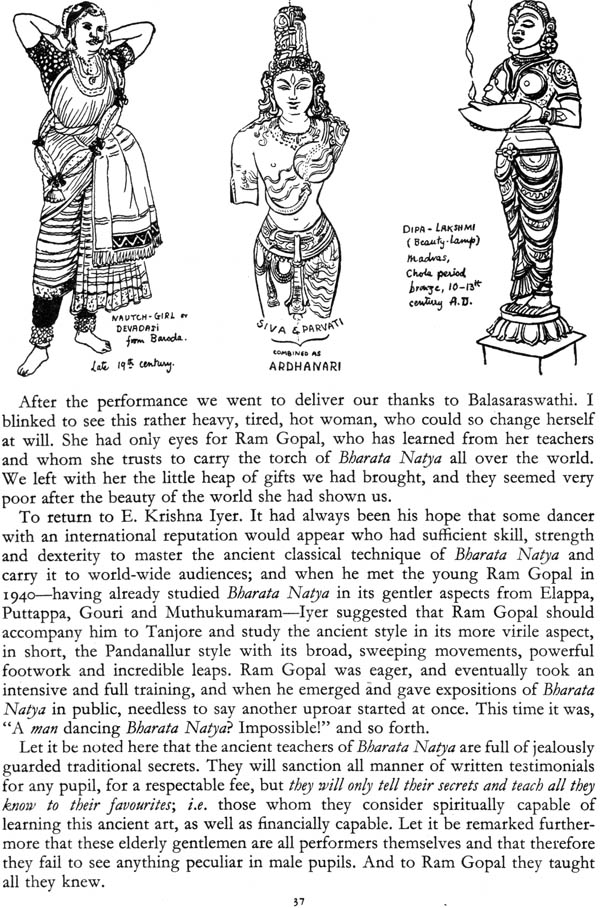

All that remains to be said is that in due course I returned to London with my company and found Londoners, along with the rest of the world, more than ready to welcome the Indian dance and Miss Ambrose, now well-versed in Indian mythology and literature, ready and equipped to deal with the realities of authorship. I started my second European tour with a season at London's Princes Theatre in December, 1947, with Miss Ambrose in attendance, making copious notes and sketches. As I had foreseen, she accompanied me on my European tour, working furiously all the time, and finally returned with me to India and completed her Indian dance education by meeting all the old great dance-masters, their prize pupils, and' attending performances of every kind including classes, rehearsals, village festivals and many other occasions which included dancing of any sort.

Following her method of studying the ballet, which she learned to perform herself so that she could sketch and describe the movements with understanding and accuracy, she has studied the rudiments of Indian dancing in the same spirit and achieved the same results; in other words her sketches in this book are accurate to a degree hitherto unknown in any country, and they conserve at the same time a strong sense of movement which is usually lacking in purely diagrammatic drawings.

I can recommend this book unconditionally to any dance-lover or student, and am convinced that in India it will become the treasured possession of every cultivated family, and the indispensable text-book of every Indian dancer.

It is the first book of its kind ever to appear in print.

Foreword

I am convinced that Kay Ambrose has asked me to write a preface to her book because she knows that I know nothing about Indian dancing. I enjoy it immensely and that is important, but the maximum enjoyment only comes with real understanding. Therefore she has written this book for me. It is clear, vivid, enthusiastic and contains some of her finest work as an artist. It is going to add enormously to the enjoyment of Indian dancing. I may even be able to borrow some of her knowledge and get away with a reputation as a pundit. Many a reputation has been founded on less.

The great hindrance to the pure enjoyment of the Indian, or for that matter the Spanish, dance lies in the use, often by the spurious critic, of the word authentic. I have seen dancing in India and I realise that it cannot be transferred to the Western stage without a process of translation. The real thing dumped on one of our stages would be intolerable, it would in fact be unreal. Authenticity is a word that needs amplification. Authenticity of spirit is the thing that counts. Ballet people have often misunderstood that when they have taken Gise!le, Swan Lake or Les Sylphides and set them down in some vast sports arena. I feel that Ram Gopal has thoroughly understood this point. Some experts may tell me that he has taken great liberties with the Indian classical dance. Of course he has, because he knows what our stage demands. But the essential spirit remains. Ram Gopal is a highly conscious artist and this translation is a conscious process. It works in practice and only when we know everything can we differ with him on points of detail. Like Kay Ambrose, I feel strongly that we must steer a clear path between semi-punditry and the intoxication of the oriental bazaar so very prevalent with those who see in every Indian a highly spiritual being. This book will help enormously in such clear thinking.

I would like to close on a personal note. Many years ago a common friend sent me a letter about Kay Ambrose. She was a ballet enthusiast and would like to sketch dancers. Of course I ignored it. Practically everyone seems to be a ballet enthusiast and wishes to sketch dancers. Then she rang me up and asked to see me. She had an attractive voice and I consented. I am glad that she had an attractive voice.

Preface

It is both customary and sensible to preface a book on dancing with a clear and brief description of the distinguishing features of the dance with which the book deals. In this case it should be explained without further ado that the four main schools of classical Indian dancing do not lend themselves easily to either brevity or clarity, which is why the rarely available books on even one style of Indian dancing usually have the effect of confusing instead of enlightening the reader.

Here I have done my best to prepare a book in which the four schools are treated with the greatest possible clarity and economy, and in their relation to one another. It must be observed that each separate school has a tradition of several thousand years, and that the history of each one is inextricably involved with the tumultuous and colourful history of the vast sub-continent of India. The main problem has been how to give clear and brief information concerning such a confused and romantic subject as that of the dances of India; if one attempted to include everything, the length of the work would obliterate its main object; yet if one left out those features relating to religion, mythology, art, environment and foreign conquests, which have made the dance what it is, one would risk being guilty of painting only half a picture.

So I have evolved a policy to solve this difficulty. There are many excellent books available concerning Indian art, philosophy, history and so forth, and in most of them are references to other books. I have added a small bibliography at the end of this volume containing a list of the most readily understandable works, contented myself with giving only the barest and most necessary outlines of Indian history that I can command, and have made sketches of just those bronzes, sculptures, murals and miniatures which are indispensable to an under- standing of the dance-and which will give the reader an obvious clue as to how he may continue to study the Indian dance on his own account. I have tried to avoid difficult words and names wherever possible; the reader can accustom himself to such terms at his leisure, with the aid of the works described.

RAM GOPAL

In the year 1939 I had seen various performances described as Indian dancing, and these performances affected me so that I had to be dragged by discerning friends to see the performance of Ram Gopal. I knew that there had been a great and ancient classical dance-tradition in India, but after seeing the only available demonstrations of Indian dancing in London I had been forced to the conclusion that Anna Pavlova's Indian informants were quite right when they told her the classical' styles were no more. I was prepared to admit that some of the dancers I had seen were genuinely Indian, but the classical style I had hoped to see was not in evidence.

An ancient classical dance-style has a force which is immediately perceptible in the theatre, and contrary to "intellectual" belief it almost invariably attracts the general public. In the same way that people are consciously attracted to any film which features the incomparable Greta Garbo-because they know that in her performance they are sure of a certain standard of entertainment-so they are attracted, but instinctively this time, by a great classical dance-style. They saw Ram Gopal, and even before he had the chance of explaining in public that his country's classical dances had survived, as he did on his return to Europe in 1947, they knew that this must be so from his dances, and flocked to admire and learn. Accompanied by raving friends, and braced against possible disillusionment, I went to a performance at the Aldwych Theatre in 1939.

Ram Gopal was then a youth who had even by that time been round the world and earned considerable fame, with solo performances at first and then the little group and orchestra which we saw at the Aldwych. Physically a stripling, the maturity of his dancing was an absolute indication that here, very much alive, was the classical dance of India, which had been thought to be extinct. I lost no time in making the acquaintance of the boy Ram Gopal, and thus my education in Indian dancing began.

Even the most unobservant reader, on glancing through these pages, must be conscious that this book is Ram Gopal. I have used his library, his collection of arts and antiques, I have been led by him through the nerve-centres of the dance in India (and these are often remote and well hidden). Ram Gopal has tirelessly performed dance-sequences over and over again, and by virtue of his extreme patience appears in the large majority of the technical sketches, all of which he corrected himself. I should like to place on record that even as the present renaissance and prosperity of the Indian dance in India as in the Western hemi- sphere is due to the faith, courage and unremitting labours of Ram Gopal, so the very existence and vitality of this book are due to him; whereas the mistakes (and there must be quite a number by the very character of the work) are mine, the lucky illuminator and scribe.

Bharata's Natya Sastra, the ancient treatise on drama, music and dancing, is the most complete Sanskrit work which remains to us in the great Sanskrit centres of India. All the fragmentary dance-dramas and styles existing to-day in both the south and the north of India are to a certain extent linked to this monumental treatise so clearly laid out in the Sastra, which is described .more clearly later on.

All the four dance-styles as mentioned above are incomplete aspects of the Natya Sastra. Many movements of gesture, expression and choreography have been lost through antiquity. The gurus or masters of the Indian dance to-day all have their own personal opinions and views concerning the original dance. For instance, the Kathakali dance-drama of Malabar has developed contrary to some of the precepts of the Sastra and is condemned by many Sanskrit professors as a result; but the deviations are carefully considered, and with a local purpose, and may therefore be considered healthy. In dancing, it is lack of principles of any kind, or meaningless adherence to pedantic traditions, which cause damage and limitation.

The four main schools are dealt with in turn in the course of this book. I believe that even the casual reader, in giving a cursory glance to the drawings, will get a strong impression of the essential precision which governs Indian dancing, and rid himself of the confused idea so carefully imparted by danseurs orientales that the Indian dance consists mainly of snake-like movements of the hips and arms. The charm of the book should also disembarrass him of the impression given by the self-styled "critic" of Indian dancing, that it is an esoteric entertainment and hard to enjoy.

PRACTICAL INFORMATION

All Indian dancing is divided into certain categories, and those which concern only certain styles will be dealt with as the occasion arises. Here we can mention the terms tandava and lasya, which are sometimes superficially translated respectively as masculine and feminine dances; this is rather misleading. Tandaua should imply a vigorous dance, lasya a soft one, and, except where otherwise stated, both aspects may be performed by both sexes. For instance, to illustrate the situation for Westerners, the male role in Us Sylphides might well be in the lasya category, with its soft and poetic flavour; whereas a brilliant technical solo for a ballerina might equally well be tandaua. The terms refer to execution, not gender, although naturally a girl performing certain tandaua dances such as those connected with the powerful cosmic solos of Lord Siva represents a sad infringement of taste (see Natanam Adinar, pages 56-57). Also the construction of the female bosom prevents a girl from taking the Nataraja pose correctly (see page 19): she should only do so in a devotional and not a representational spirit.

Mohiniattam is a dance-style which is wholly and typically lasya. It was prevalent in Malabar right up to the late 'twenties, and it is very largely composed of a fusion of the Tanjore temple-dance and the Kathakali: dance-style of Malabar. Tanjore and Malabar are geographically close.

The neck-movement-"Rechakas" is one word for it-is characteristic of all Indian dance-styles and consequently it tends to be exaggerated by amateurs, but it should be performed with subtlety. There are several varieties of this movement, the head gliding from side to side either slowly or quickly with the shoulders immobile. Its main functions are: emphasis of mood or time; rhythmical embellishment (as an entrecbat in the ballet); or purely decorative. No particular virtuosity is needed to perform the neck-movement; it is not a matter of developing extra muscles so much as discovering for oneself where the requisite muscles are situated, and controlling them accordingly.

Bare feet are a feature of Indian dancing, and here is one of the means by which the genuine Indian dancer can be recognised. Slap-slap-slap go his feet on the floor; he wears bells round his ankles, to be sure, but he must be able to maintain a clearly-defined rhythm without them which should be clearly audible. He often practises without bells in the same way that a ballerina practises without her blocked shoes to strengthen her feet.

The Natya Sastra says: "The Bells should be made of bronze or copper or silver; they should be sweet-toned, well-shaped, dainty, ;with asterisms for their presiding deities, tied with an indigo string, with a knot between each pair of bells. At the time of dancing there should be a hundred or two hundred for each foot, or a hundred for the right foot and two hundred for the left ... "-the latter is probably a practical solution to the fact that most dancers will stamp harder with the right foot than with the left one. And to-day dancers do not always tie their bells; mounted on a leather strap, or sewn to velvet-lined silk is quite common.

Investiture with bells is a great ceremony for every dancer and makes the adoption of a professional life inevitable.

Abbinaya and bhava cover gesture and expression. There are nine basic movements of the head, eight glances of the eye, six movements of the eyebrows, four of the neck, and at least four thousand single and combined gestures of the hands, specific postures for the body, the legs-specifications for everything, and each with its special name. But it is more practical to consider the complete study of this monumental technical curriculum as being in the province of the pundit, or scholar, and to enjoy the delights of Indian dancing with just those rudiments of technique which will increase our pleasure.

Any writer, armed with a good dictionary, can find enough complicated words to make himself seem clever. Using this method, a certain number of unprincipled persons have frightened off many good and intelligent citizens who would wish to study the elements of the Indian dance, by inferring that "the whole thing rests on understanding the gestures" and that this will involve dull, hard and difficult work. This should be contradicted at once, and unmasked as one of the methods used by the fake-critic to conserve the field of Indian-dance criticism and authority to himself. Gesture-language is a delightful art, as will be seen from the few examples on pages 70-71, and once one gets the general idea, easy to follow. If the reader wants further information on this subject, let him procure a copy of The Mirror of Gesture, being original texts translated by Ananda Coomaraswamy and Duggirala Gopalakrishnayya.

Contents

|

| Part I |

|

|

| Introduction | 5 |

|

| Foreword | 8 |

|

| Author’s Preface | 9 |

|

| Chapter |

|

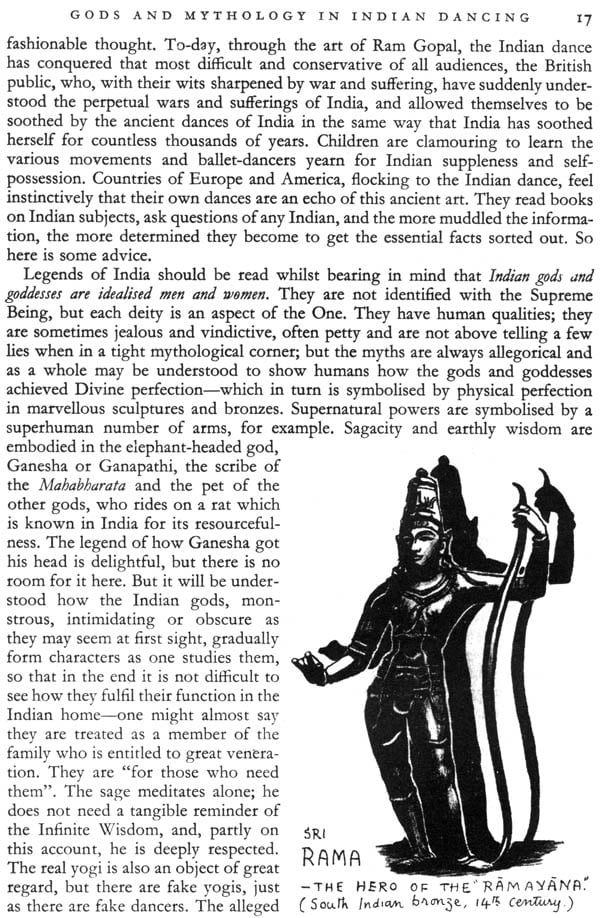

| I. | Gods and Mythology in Indian musical instruments | 16 |

| II. | Indian Music | 26 |

|

| Part II |

|

| III. | Bharata Natya, The ancient temple dance of the Tanjore | 30 |

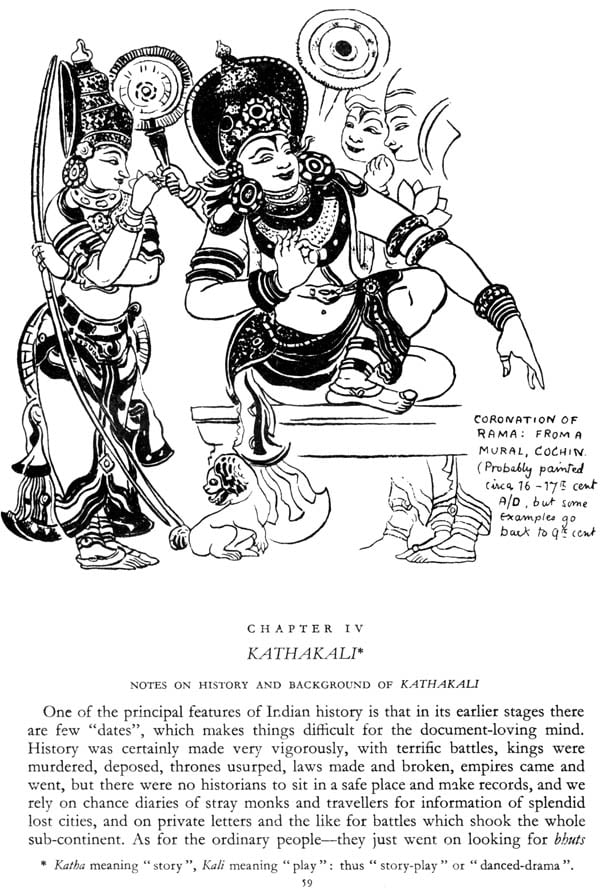

| IV. | Kathakali, The Dance-Drama Of Malabar, South India | 42 |

| V. | Kathak, the whirling dance from the North-East | 84 |

| VI. | Dance of Manipur and Assam, fron the North East | 86 |

| VII. | A Patchwork Of India Folk-Dances | 88 |

| VIII. | Dances of Ceylon | 88 |

| IX. | Costumes of India | 90 |

|

| Bibliography | 95 |

|

| Index | 96 |