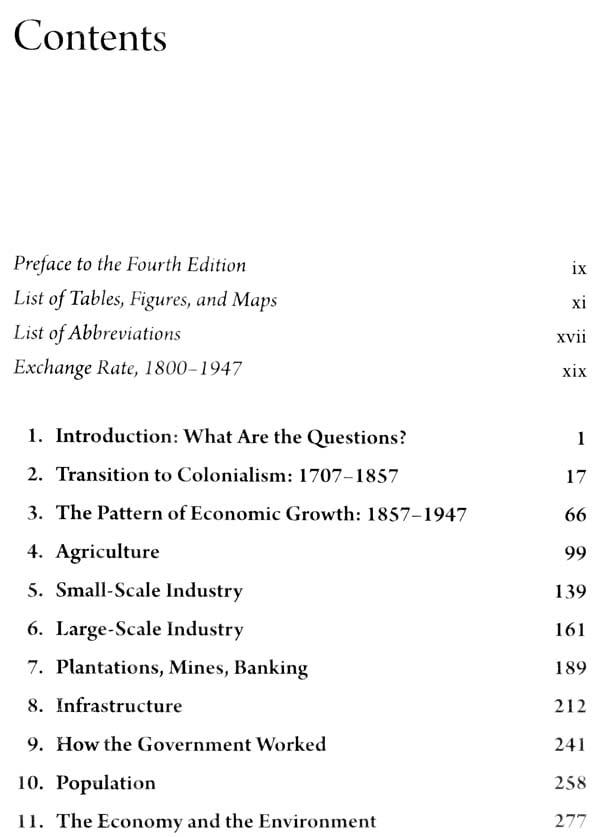

The Economic History of India - 1857-2010

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAY807 |

| Author: | Tirthankar Roy |

| Publisher: | Oxford University Press |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9780190128296 |

| Pages: | 398 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 370 gm |

Book Description

The Economic History of India, 1857-2010 claims that the roots of this paradox go back to India's colonial past, when internal factors like geography and external forces like globalization and imperial rule created prosperity in some areas and poverty in others.

Looking at the recent scholarship in this area, this revised edition covers new subjects like environment and princely slates. The author sets out the key questions that a study of long- run economic change in India should begin with and shows how historians have answered these questions and where the gaps remain.

Tirthankar Roy is professor of economic history, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, United Kingdom.

That need motivated, partly, this revision. Chapters 1 and 3 go further than before to make the general argument that economic change in colonial India was a composite of different experiences, and the task for an economic history of India is to show, not why India fell behind the world due to the actions of external and internal factors but why the same factors could generate differences within India. Chapter 13 shows how these lessons from history help us understand the present times better, when again economic growth has caused divergence and inequality within India.

Beyond sharpening the focus of the study, the revision has covered new research and scholarship, new thinking on old topics, and new questions asked recently. It has added a fresh chapter on the princely states and an almost new chapter on the environment. The years between the previous two editions of the book (2006-11) were far more dormant by comparison with 2011-18, when many studies on India appeared. The outburst is mainly due to a revival of interest in India in the economics schools of the world, matched by the response from journal editors and book publishers. The revision incorporates these developments in an area that seems to be waking up from a long sleep. The facility to cite many contemporary works made the book much shorter than the previous edition.

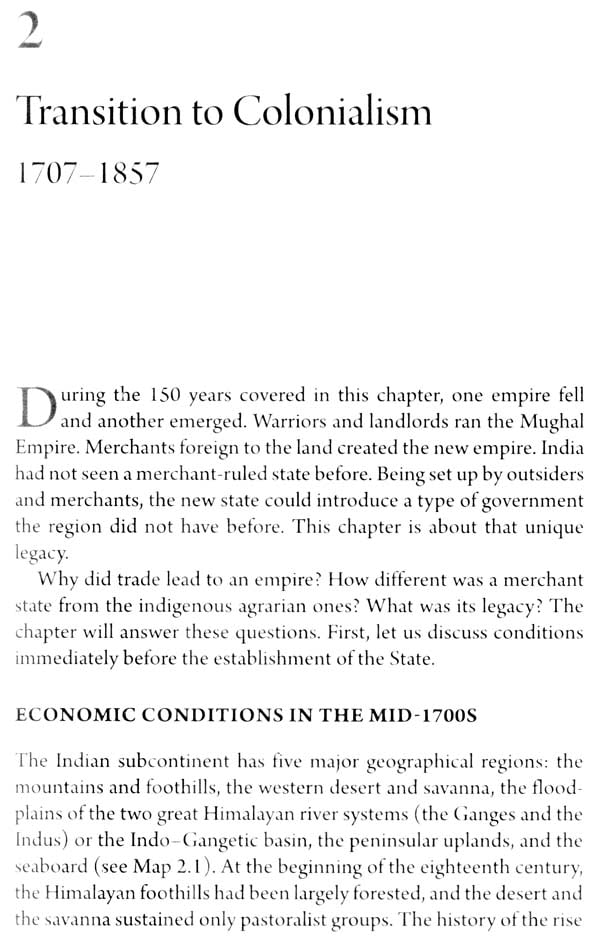

The first process, the transition to colonialism, was underway for almost exactly a century, 1757-1856. During this period, the British East India Company annexed the Indian territories that came to constitute British India. After the Battle of Plessey or Palashi in 1757, and especially after the grant by the Mughal emperor of the taxation rights of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa to the Company in 1765, the Company established a power-sharing arrangement with the nawab, or the Mughal governor, of Bengal. The partnership was an unequal one and soon tilted towards absolute control by the Company over the administration of Bengal. In 1799, the Company defeated its principal southern rival, Mysore, and in 1803-4 and 1817-18, over- came its major adversary in the north and the west, the Marathas.

In 1856, after Awadh was annexed, the British territorial campaign came to a stop.

At the end of the mutiny that took place in 1857, India became a colony of the British Crown. About 60 per cent of the land area in present India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh belonged then to British India (Table 1.1 and Map 1.1). Outside British India, there were more than 500 princely states in South Asia, nominally independent but militarily dependent on the British. They had, by then, come to terms with British hegemony, in a one-sided relationship the like of which no previous imperial power in the region could claim to have enjoyed. This relationship is sometimes called 'indirect rule, though it was qualitatively a different arrangement from the indirect rule that the European colonists developed later in Africa.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages