Goddess Lalitambika in Indian Art, Literature & Thought

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAK713 |

| Author: | C.V Rangaswami |

| Publisher: | Sharada Publishing House |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9788192698373 |

| Pages: | 296 (62 B/W Illustration) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.0 inch X 8.5 inch |

| Weight | 1.20 kg |

Book Description

The Present book attempts to study the cult of Devi Lalitambika as an individual Goddess like those of Siva, Visnu, Laksmi and others, installed independently with a long tradition and elaborate rituals, besides the highest philosophy associated with Her. The great Mother Goddess Lalita, as Her Sahasranama and Trisati, embedded in the Lalitopakhyana of the brahmanda Purana mentions, is the manifestation of a compassion besides other benign characteristics. Besides this aspect of compassion, She is also the bestower of fulfillment of all desire – worldly as well as bliss. The various forms of the Goddess although their local names are justifiably different who is worshipped by the rituals of Sahasranama, Trisati & Navavarana on the basis of Srividya and the practice of Kundalini yoga, are the representation of Goddess Lalita. She, in turn is the aspect of Mahadevi, a medieval iconographical and theological concept. Although there are a few temples of Goddess Lalita, Her abode with Seed syllables in Sricakra form are found in a number of places. This is one of Her three-dimensional forms found in a number of places.

The book consists of five chapters. First chapter is an introduction and the second deals with the Goddess in Indian Literature, which is based on Lalita Sahasranam stotra. The third chapter – Goddess in Art shows various aspects of Sricakra and the fourth one is the value of meditation as against superstitions. Besides, the value of Sri Vidya in meditation and worship of the Goddess Lalita and their several aspects are highlighted. Thousand word prayer is sung by Vasini and Vakdevis as ordained by Tripurasundari. They were communicated to Narayana or Hayagriva who subsequently imparted them to Agastya and Lopamudra. For the benefit of the reciters, the Vyakhya, i.e. single line meaning of the epithets is added in the book.

Dr C.V. Rangaswami (b.1926) had his higher education from Mysore University & Karnatak University. He served in both the universities and its colleges from 1947 to 1986 as a Lecturer in History and Archaeology and later retired as a Reader. He did his Ph.D. thesis entitled ‘The Government and Administration under the Chalukyas of Badami, under the guidance of Dr P.B. Desai, an authority in History.

In a span of 39 years (1947-86), he has published many textbooks for degree courses and more than 50 articles. His major research work with U.G.C. and ICHR are projects on ‘Revenue settlement Reports as a Source to the History of Twin Cities of Hubli-Dharwad’ & ‘Sri Lalitambika in Literature, Art and Thought. Other major research work is on Sri Pitambara Devi (Devi Bagalamukhi) in Socio-cultural Field was submitted to the ICHR, New Delhi. He has written a short book on ‘Siddha Paravatavasini Devi Bagalamukhi (Pitambara Mai)’ and edited ‘Bagalamba Sataka’ of Cidananda Avadhutaru Rajayogi, and ardent worshiper and saint at Sindhanur near Raichur district, Karnataka. At the age of 86, the author is still active in writing books and articles.

Offering my profound obeisance to Sri Lalitambika and the galaxy of scholars on Srividya and Upasakas through the ages right from Bhaskararaya Makhin, Sir John Woodroffe and others, I have made an attempt in the book to write on Lalitambika in Indian Literature, Art and Thought as an individual Goddess installed independently with a long tradition and elaborate rituals, besides the highest philosophy associated with Her, as in the case of deities like Siva, Visnu, Brahma, Rama, Krsna, Skanda, Surya, Vinayaka and their female counterparts or consorts. However, emphasis on the philosophical aspects is to a limited extent only, as much has been written on it. It is only in recent years that scholars like David Kinsley and of the Ramakrishna Order and a few others have treated the Goddess independently in their works. Although some philosophic systems and spiritual thought insist that all gods are actually manifestations of one god or one Ultimate Reality, most myths and texts deal with male, sometimes, a few feminine deities as individual beings. The Vedic saying, ekam sat vipra bahudha vadanti (the essence is one, but the sages describe it variously) indicates the importance and popularity of stotras relating gods-goddesses. Similarly, the saying in Kannada, devanobba nama halavu (god is one, but his names are many) connotes the same meaning.

Worship of the Divine Mother is a common phenomenon not only in the south but in north India also. Indeed it is possible to view it in a world perspective as Friedrich Heiler observes. To cite him, "the conception of God as Mother is as natural and ultimate as the conception of Him as Father and that it has prevailed in every part of the ancient world. In particular, the Cult of the Great Mother had a strong impact in Egypt, Israel and the countries of the Mediterranean" (Das Gabet).

It is apt here to point out that Payne has rightly commented in the Saktas that India is unique in sharing a higher reference to goddesses in its later developments than its earlier, unlike other countries where with advancing civilization, the importance of the feminine principles as a constituent of religion, has progressively decreased. Starbuck in his article 'The Female Principle' in the Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics notes that in the comparatively primitive conditions of life depicted in the Vedas, goddesses have a very minor place in the Pantheon, but after the Nation settled down to peaceful life and agricultural pursuits, the worship of the Female deities has risen to a place of supreme importance. He attributes this to the high position accorded to women in India from early times.

Hindu goddesses are different from one another. If some have strong maternal nature, others are not. The great Mother Goddess Lalita, is as Her Sahasranama and Trisati, embedded in the Lalitopakhyana of the Brahmanda Purana, mentions, is the manifestation of a compassion besides other benign characteristics. She is described as Avyajakaranamoortaye namah (name 992) and Tirodhanakarisvari (name 270 Goddesses (Lord) of preservation). Besides this aspect of compassion, She is also the bestower of fulfillment of all desires - worldly as well as bliss. She is also the bestower of sivajnana (name 727 knowledge of the Absolute).

Throughout the book, I have assumed that the various forms of the goddess although their local names are justifiably different who is worshipped by the rituals of Sahasranama, Trisati and Navavarana on the basis of Srividya and the practice of Kundalini yoga, are the representation of Goddess Lalita. She, in turn is the aspect of Mahadevi, a medieval iconographical and theological concept. The main point of difference between goddess Lalita and others is that She represents the benign form and Her ritual is also insisted on sattvikway, since the time of Sankaracarya, He advocated the Samayacara or Daksinacarya system of goddess worship and regarded Her as the Mother. He saw the Ultimate Reality (Brahman) in the Mother Divine. The Guru of Lalita rituals is Daksinamurti.

The book consists of five chapters with appendices, glossary, bibliography, index and illustrations.

In preparing the book, I made a study of the related original and secondary sources from which I derived much benefit, a list of which is given in bibliography. I also made a discussion on various aspects of the problem with Svamijis, Heads, Trustees of several temples, mathas and individual scholars, a list of which is given under acknowledgement to whom I am much grateful. This is a resume of the Major Research Report financed by the University Grants Commission, New Delhi under the scheme - "Support for Major Projects - Superannuated Teachers".

As there is a sectional treatment on the Goddess Lalita, in recent publications, I hope this book would contribute to some extent in filling up the gap and add to the existing literature.

Whatever a man undertakes to do, he wishes to complete it without any obstacle. If the wish is to be fulfilled, his own efforts are not enough. He needs divine grace for that. We must therefore worship god (fig. 1) or goddess. Of the many forms of goddesses Sri Lalitambika is one.

Worship of the Mother Goddess

Meditation and modes of worship are known as upasana which are embedded mostly in the Prasthanatrayas. Of them, the Upanisads contain the experiences of sages of ancient India who in turn taught their experiences to others. Upasana includes not only acquisition of theoretical doctrines but making it one's life-breath. The aspirant (sadhaka) could meditate on any god or goddess as he desires. As the mind gets concentrated on the personal god or goddess, the aspirant proximates nearer to the Absolute Reality (Brahman). He realises the fundamental Vedic dictum that 'Truth is one; Sages call it by different names.' Therefore, meditation lies in concentrating the mind on the Brahman for which the basic requirement for the aspirant is purity of mind. A step ahead of this stage of spiritual attainment has been shown to us by Paramapujya Sri Atmananda Svamiji, Sureban-Manihal (Ramdurg taluk/ district Belgaum), who taught us in a series of discourses that 'Bliss is one with Humanity' and the aspirant is only to realize the Upanisadic dictum that he need not attain union with the godhead by his spiritual process but he is himself the godhead. He is only to realize this by giving up adhyasa (nescience). The Svamiji taught us in the line of ancient Indian sages such as the Vedic Seers, Sri Sankara, Svami Vivekananda and Sri Ramana Maharsi of recent years. In one of the discourses at Raddera Timmapura (Badami taluk, Bagalkot district) he gave a befitting reply to a comment made by Mr. Tuchesman, a renowned spiritualist and philosopher of U.S.A. who said that Bharata (India) is non-existent since 1500 years. He observed that "Bharata is not dead (spiritually) but lives even to this day". Appendix I contains the life and work of this most unassuming compassionate, yet firm in his dialogue with his fellowmen and the founder of several institutions (asramas) in North Karnataka on the model of ancient Indian Gurukula with no accumulation of wealth and property but with the sole purpose of propagating Brahmajnana (Knowledge of the Absolute) without any discrimination of caste, sex, colour or status. He led such an exemplary life of 'simple living and high thinking' that anyone could follow and be proud of.

If meditation is not possible, one could do japa or think of the names of the deity in one's mind. No doubt, we do not know the form of god/ goddess. But He/ She has several names. Each name is full of divine implications. It is easier to utter His/ Her names and thereby attain Self-realisation. There is no other simple way. For external worship, we need props which are not required for japa. For instance, it may be recalled here that Sivapancaksari mantra mentioned in the Satarudriya of Yajurveda, as vouchsafed by the Lord Himself, could be contemplated upon by the devotee, anywhere and at any time, while he is walking in the street, where he stands, where he does service and even when he is impure, physically. The status or caste of the devotee is of no concern to the Lord.

Sometimes, it may appear that uttering the same name several times is bereft of diversifications. At least in the initial stage of sadhand, the aspirant requires variety. Thus he has the choice of uttering (parayana) various names relating to his personal deity. Texts on parayana are mainly three Lalitasaharanama Visnusahasranama and Durgasaptasati. Generally speaking, recital of Lalitasahasranama or Visnusahasranama is very common in many houses. The Durgasaptasati is recited normally during the Dasara Festival or sometimes to overcome afflictions. Among the Sahasranamas, Lalitasahasranama is the most beautiful and blissful.

In this religious art based book, an attempt is made to study the attributes of Sri Lalitambika as described in the Lalitdsahasranama and related literature and as depicted in art and also forms of the goddess in the main centres of Sakti worship or Srividya worship of South India with reference to ramifications and rituals in the Srividya/ Sakti Pithasand .K;5etrasand finally to evaluate the place of Lalita cult in thought from the point of leading a life free from disease and in perfect harmony with Nature. The study is based on the available literature on Srividya and results of Field Study in main centres of Srividyaz Sakti worship in South India.

In terms of chronology, the study is broadly based from tradition to modernity.

Purpose of the Study

The aspects investigated in the foregoing pages may be analysed as follows:

Though there are very few temples named particularly after the goddess Sri Lalitambika or Lalita as for instance, the Lalita Tripurasundari temples in Mahabalipuram and Kurtalam (Tamil Nadu), Mugur (Chamarnagar district, Karnataka), the presiding deities in most of the Srividya- pithas of South India are but the forms of goddess Sri Lalita as described in literature and prayers, although they bear, justifiably, different local names. Worship of the goddess, installed independently invariably with the Sri Cakra or Meru on the basis of the Navavarana, Lalitasahasranama, Lalita Trisati by the samayacara mode would be a significant factor to be taken into consideration in this regard. Besides this, the entire ritual of Lalita worship begins and close for the day as in Srngeri with the svastivacana in the name of Sri Mahakali, Mahalaksmi, Maha Sarasvati (the cardinal principle running through Durgasaptasati), aikya (antargata) Sri Lalita Maha Tripurasundari. The conception of goddess Lalitambika has continued from tradition to this day as can be seen, among several others, from a temple named, Lalitambika in Gadag (Karnataka) and an ivory figure with ten hands, beautifully carved, kept in the Sri Manjunathesvara temple Museum at Dharmasthala (Daksina Kannada district).

Sri Adi Sankaracarya installed and consecrated Sri Cakra in several temples all over India. While mentioning structural temples, we have to make reference to Sri Annapurnesvari temple, Horanadu (Chikmagalur district, Karnataka) where the jagati of the temple is in the form of Sri Cakra. Another instance is that of Sri Candralamba temple, Sannuti (Gulbarga district, Karnataka) where the pyramid is in the form of Sri Cakra. In Hebbur (Tumkur district, Karnataka) the Kamaksi temple is in the form of Meru prastara.

Another significant point to be noted is the Angkor Wat temple (Cambodia), which is in structural aspects is similar to Sri Cakra. In the 5th century A.D. (the Gupta period) Indian culture dispersed to south-eastern countries (Greater India) such as Java, Bali and Sumatra. Probably, the Ankorvat temple is comparable to Sri Cakra in technical structural aspects was also built in the 5th century A.D. That in structural aspects the temple is similar to Sri Cakra is also the opinion contributed for the first time by Late Dr. S. Sreekantha Sastri, Professor of History, University of Mysore, Mysore.

The Sri Cakra is primarily a yantra, the form and pattern of the deity. It is one of the three modes by which gods and goddesses of Hinduism are generally represented, namely the murti, the yantra and the mantra. The murti is the three dimensional form which can be sculptured, the yantra, a two dimensional or geometric pattern which can be drawn and the mantra, the sound form or the thought form, which can be uttered in contemplation." The dhyanamantra describes the murti. The tantric works describe the yantra and the mantra. Worship of the Sri Cakra is associated with the worship of Goddess Sri Lalita and also the highest philosophy emerging out of it, as mentioned already.

While making a note of the ramifications of the Srividya/ Sakti-pithas, ksetras and tirthas in south India, the rituals could be traced from tradition to modernity. In many of the ancient and medieval pithas, the mode of worship of Goddess Sri Lalita are according to tradition, but a modern instance," (e.g. Devi Bagalamukhi as pitambara devi) as late as the 18th century and contemporary period may be cited here as an instance in point. A great saint named Cidananda Avadhutaru (fig. 3) who carried on meditation and practised kundalini yoga, as an integral part of Lalita rituals, on the hill named Siddhaparvata (Ambamatha, near Sindhanur, Raichur district) flourished in the 18th century. He is the reputed author of several works on Devi worship and spiritualism, including the Bagalamba Sataka, Devi Mahatme and jnanasindhu. In the Bagalamba Sataka we find described not only the mode of worship of De vi Bagalamukhi and Bagala yantra but also the evaluation of the saint from the stage of a sddhaka to 'bliss'. A brief note on the life and work of the saint is given appendix II. The ritual-tradition was further continued till very recently, by a life-time Sri Devi upasaka, named Sri Paramapujya A.N. Hurakadli, popularly known as Hurakadli Ajjanavaru in his asrama at Navalgund (Dharwad district) (fig. 4). A remarkable feature of this dsrama is once again not accumulation of wealth and property, but making accessible to everyone, without distinction of caste, colour, creed, sex or status, to obtain solution to his personal problems and even to undertake meditation depending on his ability. A note on the life and work of the saint who left his mortal body in January, 1990, after a dedicated life of nearly a century in Deoi Upasana and Lokakalyana (strain oneself in achieving welfare of humanity as a whole), has been given in appendix III. As he worshipped the goddess as Gauri, the pitha could be called as Gauri-pitha.

In the book, an effort is also made to estimate the impact of Lalita cult on human thought. Apart from active participation of the common man in corporate life, largely in ancient times, but getting their revival in recent years, such as fairs and festivals, a happy trend of individuals taking to a life of meditation, is noticed. Not that the entire society is to take to meditation; it is not practicable also. For anubhava (self-realisation) is not possible to be attained in mass meetings, though guidelines may be secured. Anubhava is purely a personal experience as a result of one's spiritual attainments and cannot be experienced by others. In evaluating the practice of Lalita cult, the baseless social evils and superstitions like nude worship and other feminine social problems have no meaning. Because the matrix of rationale behind the cult is realization of 'Bliss' which is one with humanity, irrespective of social discrimination.

Furthermore, to restore values based on the country's spiritual and cultural heritage, it is necessary to recall to ourselves the need for an ethical code of conduct which would help growth of a large percentage of 'Social Citizenry'. There is ample truth in the saying daivam manusa rupena. In modern times, Nature is symbolized with god. At a critical time, full of tension and changes in lifestyle, when man is not afraid of authority or his conscience, it is necessary to make people realize the value of an ethical code of conduct by education to develop human resource. Again, at a time when the genuine basis of the rituals of Mother Goddess cult is lost sight of, and their rationale aspect overlooked, it is also necessary to emphasise that righteous living needs only a will and discipline and not excessive wealth beyond the means of subsistence or spend pompously on blind beliefs or to satisfy one's ego or become the victims of degenerated black art and Vamacara practices.

| Preface | xi | |

| Acknowledgements | xiii | |

| Abbreviations | xv | |

| List of Illustrations | xvii | |

| Chapter 1 | Introduction | 1 |

| Chapter 2 | Lalitambika in Indian Literature | 31 |

| Chapter 3 | Lalitambika in Art | 75 |

| Chapter 4 | Lalitambika in Thought | 109 |

| Chapter 5 | Epilogue: Ancient Solutions to Modern Problems | 143 |

| Conclusion | 149 | |

| Appendix I: | Life and Work of Sri Swami Atmananda | 153 |

| Appendix II: | Life and Work of Cidananda Avadhutaru, Rajayogigalu | 155 |

| Appendix III: | Life and Work of Sri Paramapujya Harakadli Ajjanavaru | 157 |

| Appendix IV: | Camundi Hill (Naksatramalika) | 159 |

| Appendix V: | List of Sakti-Pithas (108) | 163 |

| Appendix VI: (A) | Lalitasahasranama Stotram | 167 |

| Appensix VI: (B) | Sri Lalitasahasranamavali | 173 |

| Appendix VI: (C) | Vyakhya | 187 |

| Appendix VII | Navavarana Puja | 225 |

| Glossary | 233 | |

| Bibliography | 245 | |

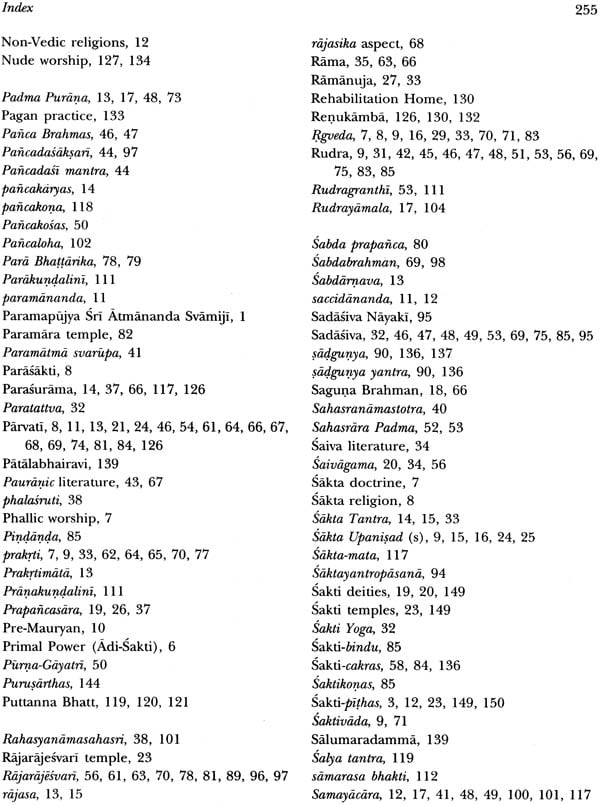

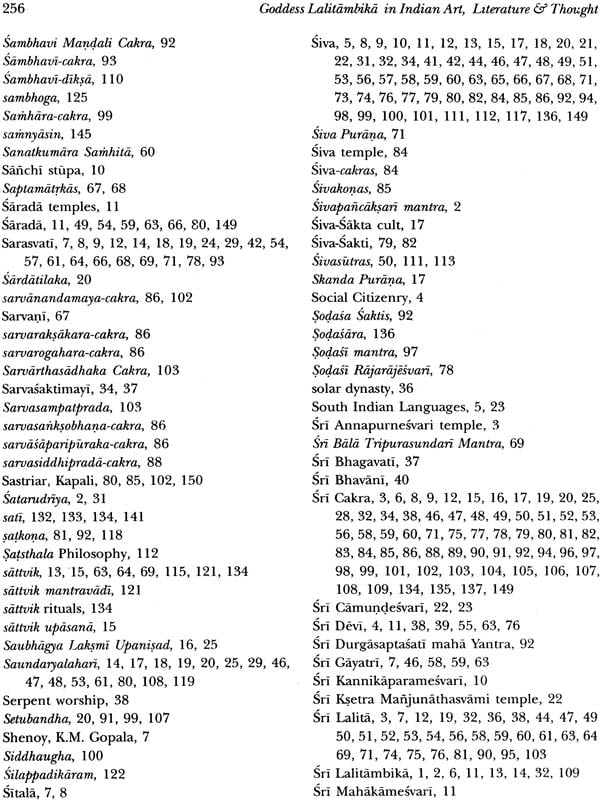

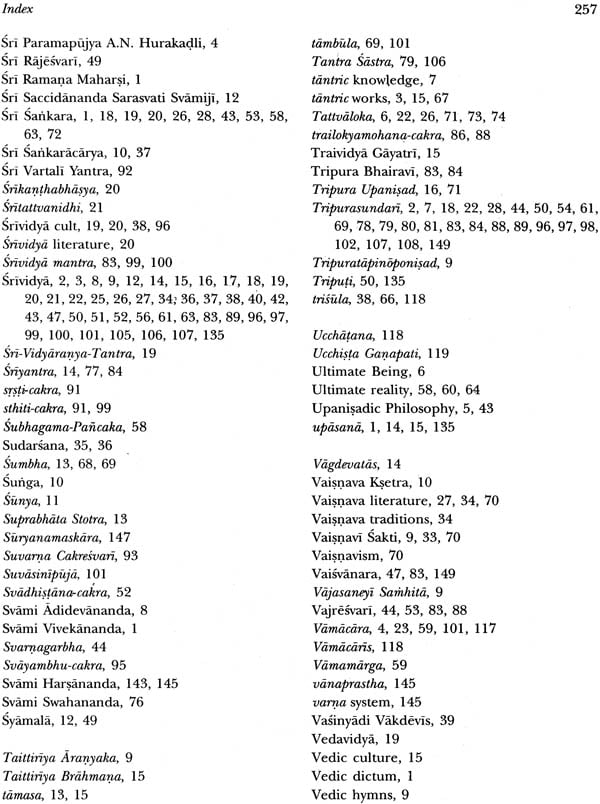

| Index | 251 |