The Hindu Rite of Entry Into Heaven: and others Essays on Death and Ancestors in Hinduism

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAQ698 |

| Author: | David M. Kinpe |

| Publisher: | MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2019 |

| ISBN: | 9788120842441 |

| Pages: | 348 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 460 gm |

Book Description

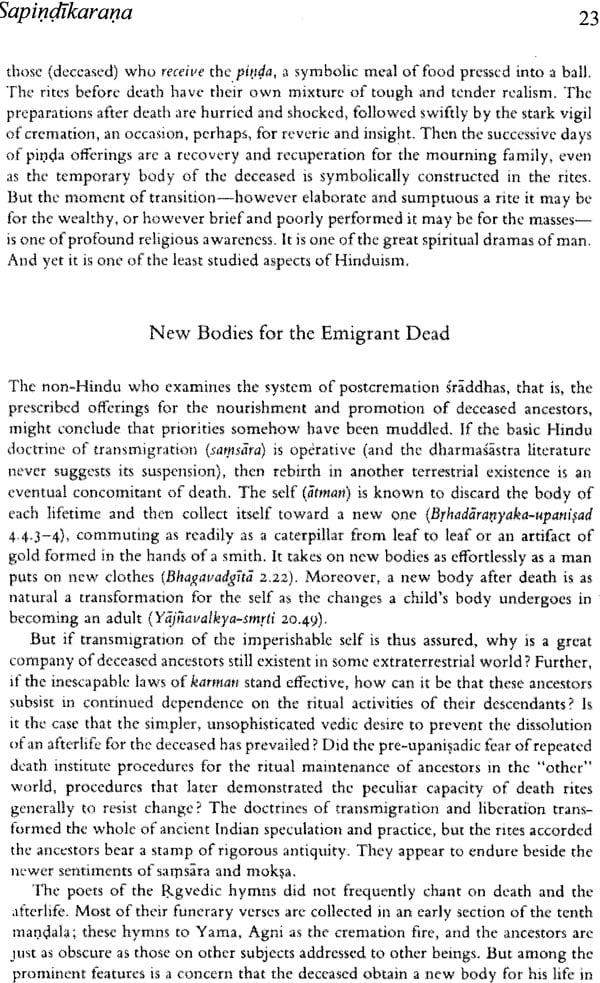

This book comprises a smorgasbord of essays on death, dying, funeral rituals, ancestor ceremonies, ghosts, and other subjects in the realm of Mrityu, the god of Death, and aparam, the Sanskrit and Telugu word for human End Time. The focus stretches from the Rig Veda to present-day Hinduism, textual and non-textual. The title of the book is that of the first essay, an ethnographic and Vedic/Classical Sanskrit textual study of the sapincla ritual that occurs on the twelfth day of a full-scale, textually accurate funeral. That field work was accomplished during a year-long study of funeral rituals in Varanasi, the ancient city of Kali where it is most auspicious for Hindus to die and be cremated in a final sacrifice of the body.

This book comprises a smorgasboard of essays on death, dying, funeral rituals, ancestor ceremonies, ghosts, and other subjects in the realm of Mrtyu, the god of Death, and aparam, the Sanskrit and Telugu word for human End Time. The focus stretches from the Rig Veda to present-day Hinduism, textual and non-textual. The title of the book is that of the first essay, an ethnographic and Vedic / Classical Sanskrit textual study of the sapinclikarana ritual that occurs on the twelfth day of a full-scale, textually accurate funeral. That field work was accomplished during a year-long study of funeral rituals in Varanasi, the ancient city of Keg where it is most auspicious for Hindus to die and be cremated in a final sacrifice of the body. Much of Hindu belief and practice stems from the personal fate of the preta, also known as the jiva, that survives obliteration of its used body. The essay was originally published in Religious Encounters with Death. Insights from the History and Anthropology of Religions, edited by Frank E. Reynolds and Earle H. Waugh (University Park & London: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1977), 111-24. It was reprinted in Religious Approaches to Death, edited by David G. White (2d ed., Dubuque: Kendall Hunt 2006), 163-77. My intentions with this field study were first to provide textual and photographic documentation of one paradigmatic ritual in the extraordinarily rich and complex social and geographic diversity of Hindu funerary practices, and second to open for inspection graddha traditions in the key period of transition from Vedic to Puranic practice. For a detailed analysis of this essay in the context of the emergent doctrine of karma and the twin processes of death and birth see Wendy Doniger 0 'Flaherty, Karma and Rebirth in Classical Indian Traditions (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980) 3-27. There are further comments on the essay by Matthew Sayers in his book mentioned above, pp. 1-8.

The need for a wide range of ethnographic studies of Hindu funeral and ancestor rituals is still a pressing one, particularly in an age when religious customs are rapidly changing and countless routines disappearing. When Indira Gandhi was assassinated on October 31 1984 worldwide television coverage of her cremation funeral was an opportunity for millions to observe orthodox practice. I was enlisted by the NBC News Network to provide step-by-step commentary. Outsider perception of that event, however, could not reveal the fact that every day in India thousands of people who consider themselves Hindus are given non-Brahman rituals including earthen and riverine burials. My curiosity about dying in India led me to engage in "hands-on" ethnography, including getting down and dirty in the grave or by the pyre amid the detailed dramas of one person's departure.

I provide here a single illustration out of scores of possible examples: Ram, a 56-year-old Kamsah, was buried in a cremation / burial ground close by the Godavari River outside the town of Rajahmundry in Andhra Pradesh. Kamsalis, Goldsmiths by trade, prefer to be known as Vigvabrahmans and consider themselves higher than Brahmans in the social hierarchy. With drums, flutes, and great ceremony Ramu was carried like a saint seated upright on a flowered palanquin topped by a scarlet canopy. I joined the street procession and with the family's permission photographed all of this colorfully detailed ceremony. I was invited to step down into the open grave to help the hired grave-digger's final task, a careful carving of a niche to prop steady the seated man's head. I cradled Ran’s head on my shoulder while the grave-digger chiseled out the exact space. Ramu's thumbs were tied together with a cord that stretched up to a stake at ground level. The grave-digger and I climbed out, Rainu's pit was back-filled, and the area received a distribution of bright red, yellow, and orange powders. The following day we all returned to that stake with a full-course dinner, a thalr bhojanam on a metal platter. All his favorite foods were poured, one dish after another, into the hole exactly above the hands of Ramu, now seated comfortably six feet underground. There was even his favorite newspaper laid out for him.

India is replete with such non-textual, virtually undocumented customs that are never curious to those who carefully send loved relatives to the other world. It is obvious too that those who keep death pollution at a far distance and never consort with those despised professionals who manage final rites (their names and faces should never be remembered) are less than eager to engage in ethnographic studies of funerals. Too many of these revered funerary customs now disappear without a trace.

The second essay in this collection is "raddha," a brief definition of a key term in Sanskrit textual traditions concerning "funeral and ancestor rituals." It appeared in the Abingdon Dictionary of LivingReligions, edited by Keith Crim, et al. (Nashville: Abingdon 1981) 713-14; republished as The Perennial Dictionary of World Religions (San Francisco: Harper & Row 1989). I include it here for the opportunity to provide a photo illustrating the elaborate provisions for the departed in raddha. The karta (chief mourner) depicted here has completed the sapirklikarana for his father on the twelfth day after death. Aided by a family priest he is now making offerings of pinda-s, water, lamps, incense, and threads for clothing that will provide satisfaction during his father's year-long journey to the other world.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages