Laments in Sanskrit Literature (From C. 1500 B.C. to C. 1100 A.D.)/ Old And Rare book

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDE568 |

| Author: | Sures Chandra Banerji |

| Publisher: | CHAUKHAMBHA ORIENTALIA, Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1985 |

| Pages: | 237 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.8" X 5.4" |

Book Description

From the Jacket:

The present work, first of its kind, is a collection of laments in Sanskrit literature since Vedic times down to the classical age, followed by translation. It spans a period of roughly 3,000 years. In the introduction, the general characteristics of the laments have been discussed. Under each head, the content, the occasion of the lament, etc, have been indicated. At the end, there is a list of grammatical solecisms and a glossary of difficult words.

About the Author:

Dr. Sures Chandra Banerji (b. 1917), a distinguished scholar, served the Dept. of Education, Govt. of Bengal (afterwards, West Bengal), as Prof. of Sanskrit and Secretary, Vangiya Sanskrit Siksa Parisat, for thirty years. He published about a hundred original papers in different Indological journals. He has to his credit thirty-six treatises, in English and Bengali, relating to various aspects of Indology, particularly Sanskrit literature. He was awarded a Rabindra Memorial Prize (1963-64) for his Bengali work on Smrti literature. His name and works have been included in 'International Writers Who's Who', London, and 'Indian Writers Who's who', Sahitya Akademi. A Life Member of Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona, he is a member of the Bibliotheca Indica Committee of Asiatic Society, Calcutta, and f the Ramakrishna Mission, Calcutta and Bharatiya Vidya Bhawan, Bombay. He was a quondam Guest Lecturer of Calcutta University.

Among his English publications are A companion to Sanskrit Literature (1971), Indian Society in the Mahabharta (1976), Flora and Fauna in Sanskrit Literature (1980), Crime and Sex in Ancient India (1980), Tantra in Bengal (1978), Sanskrit beyond India (1978), Dharmasutra - a study (1965), Cultural Heritage of Kashmir (1965), Kalidasa Kosa (1968), Sadukti-Karnamrta (ed.)(1965), Vikramankadeva-Carita (trs.)(1965), Smrti Material in the Mahabharta (1972). His Samgita-ratnakara (1380 B.S.) is a Hindi translation.

As a boy, I used to be shocked by plaintive wails, especially of rustic women, wafted through air from afar. On carefully listening to the same, I could hear the wailing woman recounting her diverse memories associated with her dear one departed to the bourne whence no traveller ever returns. Such loud laments are rare in sophisticated societies. It is considered to be an essential part of civilised conduct to control emotions before others. For this reason, now-a-day introverts are generally preferred to extroverts. In primitive societies, however, people appear to have been more free and frank before others. Consequently, they did not hesitate to express the feeling of joy or sorrow with natural vehemence. In some cases, loud lamentation was regarded as a positive evidence of one’s fond attachment to the person of whom one had been bereft for ever. A ridiculous result of this idea was that sometimes loud laments were indulged in even when the grief was not genuine or poignant.

When I got some access to Sanskrit literature, I discovered that laments constituted some of the finest gems contained in it. Moreover, I was struck by the similarity, in many respects, of these laments with those heard by me in my boyhood among the rural people. Since then I have been haunted by a strong desire to study the laments in Sanskrit. The result is the present humble work. Vast in extent as Sanskrit literature is, I have culled only the prominent laments. As far as I know, this aspect of Sanskrit literature has not yet received the adequate attention of scholars.

In an attempt to make the collection as representative as possible, it has been divide into four sections, viz. Vedic, Epic, Puranic and Classical. The reader will thus have a glimpse of an aspect of Indian life through different ages. The collection represents the period from the Rgveda to the Naisadhacarita, that is, a span of roughly two thousand five hundred years. Besides the unknown or legendary author or authors of the Rgveda, of the Epic and the Puranas, the collection places before the learned reader such masterminds as Asvaghosa, kalidasa, Banabhatta, Sudraka, Bhavabhuti and Sriharsa. Sanskrit anthologies abound in single stanzas deploring or lamenting over various misfortunes of life. These, however, have been ignored for the present purpose. At first, we have given an introduction setting forth the general characteristics and classification of the laments, the peculiarities of ancient Indian psychology and society revealed therein and then a literary estimate.

The introduction is followed by the text. Each lament is preceded by brief introductory remarks stating the occasion and the persons concerned and laying down a short account of the contents. So far as the Mahabharata is concerned, we have used the critical edition of Poona. In the case of the Ramayana, the edition of Chaukhambha has been utilised.

Then follows the translation which is as literal as possible. In the case of elliptical sentences of the original, the suggested missing words have been translated within brackets in order to make the sense complete and easily intelligible. The word ‘dharma’ occurs many times in the passages, culled by us. In the absence of a single English word, conveying the import of ‘dharma’ , we have left it untranslated. According to Mimamsa philosophy, it means that which induces a person to do something salutary. In different contexts, it means also a set of doctrines, dogmas, faiths, religious practices, duties, etc.

We have added three Appendices. In one appendix, the un-Paniniyan forms, occurring in the passages, have been collected with short comments against each form. In another appendix we have collected the technical and difficult words which may prove to be stumbling blocks to the reader of the texts. All the meanings of each such word have been written so that the reader can judge whether the meaning, stated in the translation, is appropriate or not. Some of the passages contain mythological or legendary allusions. In one appendix, brief notes on these myths and legends have been added to enable the reader to grasp the meaning of the passages concerned.

If a person weeps, every one, with a feeling heart, will sympathise with him. Let us, dear readers, wait with a sympathetic attitude, in order to listen to the laments, recorded in the tape of literature and reverberating through two millenaries and a half. Here we shall find Soka transformed into Sloka.

One may wonder why we have chosen laments as our subject, while Sanskrit literature is replete with accounts of love, heroism, devotion, and is rich in the comic element, descriptions of nature and landscapes of diverse types. So, a word is necessary in justification of the selection of this particular them.

It is a psychological truth that the karuna-rasa or pathetic sentiment touches the heart much more deeply than other sentiments of which there seven or eight (nine including Santa or the quietistic) according to Sanskrit poeticians and dramaturgists. The English poet asserts that our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thoughts. Bhavabhuti, one of the great Sanskrit dramatists, and perhaps the most masterly delineator of the pathetic sentiment, has no doubt that there is but one rasa or sentiment and this is Karuna. It is, according to him, the substratum of all other rasa which are nothing but manifestations of the one single basic Karuna. These manifestations are caused by different occasions. If this is true in life, it is no less so in literature. The reader enjoys a literary piece full of pathos; he reads and re-reads it. Herein lies the superhuman nature (alaukikatva) of Kavya-rasa. In life, no one would like the repetition of a tragic event; one would turn back from a pathetic incident.

Human heart is, so to say, like the sapta-tantri, it has several strings. Like the latter, it has several cords each of which is touched by karuna-rasa. This is the reason why we have chosen laments in Sanskrit literature as the subject of our present study. It is with a view to sharing, with the reader, the aesthetic pleasure we derive from them we have undertaken this study.

In a person’s lament we find a reflection of his heart. When a person is overwhelmed with grief or self-disparagement, he speaks from the core of his heart. In a lament, we see the inmost recesses of the human heart; the person concerned spells out his anguish without any reservation whatsoever. In our day-to-day life, we often resort to inhibitions, lies, pretensions, shams, frolics and frivolities. But, no artifical cover hides the heart of one, stricken with grief. Thus, the laments in Sanskrit literature reveal an aspect of Indian mind, and for that matter, of Indian culture.

Sanskrit literature is rich in laments from the remote Vedic period down to the Classical times. The laments are of various types, e.g., self-disparagement, mourning over the dead, pangs of separation from dear ones, etc. While requiems or dirges in the sense of special mass for the repose of the departed souls are unknown in Sanskrit literature, elegies are found is abundance. Laments are naturally very few in Vedic literature. In that age, when people had robust optimism, when they did not yet develop the spirit of servility to gods with whom their relation was one of give and take, when the philosophical doctrine of illusion did not yet grip their mind, when the philosophical doctrine of Karman did not yet kill human initiatives, occasions for lament were but few. By the time the epics assumed their present from, the above philosophical doctrines clouded human mind, they learnt tamely to submit to what was destined, and developed a sense of aversion to the phenomenal world which, as the philosophers preached, is an illusory appearance of the Supreme Sprit. The doctrine of Karman and the idea of the omnipotence of gods permeated the society of the Epic, Puranic and Classical Indian. The epics, which reflect a warlike age and which related the human story of this vast land, are naturally full of laments over the heroes killed, the beloved abducted and the dear ones separated. The avowed object of the Puranas was to preach and propagate sectarianism. The Puranic stories are mostly propagandist and doctrinaire, designed to boost the particular sects glorifying their respective deities. Some of the Puranas or their parts were compiled with the deliberate aim of saving the sacerdotal class from grave economic crisis. By the time these works were composed, Buddhism, which gave greater latitude to women and Sudras than the Brahmanical religion and the society guided by the Smrtis, posed a serious threat to the Brahmanical society. The downtrodden in the society began to embrace Buddhism in large numbers. It was, at this time, that the clever Brahmins compiled some Puranas, women and Sudras were given greater freedom in religious practices than before. They invented a net-work of Vratas fasts, places of pilgrimage, etc. in order to appeal to human sentiment, especially the sentiment of womenfolk. They also glorified gifts of various articles including the daily necessities of life-bed, umbrella, sandals and the like. They held out great rewards both in this world and in the next, which would ensue from the performance of the Vratas and the making of gifts. This ingenious device served to keep a number of women and Sudras within the Brahmanical fold and to cater to the economic needs of the Brahmanas. Such having been the background of the Puranas, there was little scope in them for the development and expression of the finer human feelings or the romantic setting which gave rise to laments.

Coming down to the classical times, we notice, in the lements, pathos tinged with romanticism. The very circumstances, under which Indumati dies causing Aja to resort to bitter lament, Cupid is reduced to ashes leaving his mourning spouse, Rati, the golden swan gliding over the placid water of the lake bemoans the lot of his family in grim anticipation of his death at the hands of Nala, Mahasveta laments over her misfortune at the separation of Pundarika, are all romantic. A different atmosphere over his ignominious plight caused by a malicious scandal in the bourgeois comedy called Mrcchakatika; it is the wonded self- respect of a noble man that gets a tongue. The laments of Suddhodana, Yasodhara and Gautami at the disappearance of Gautama in the Buddhacarita are the normal reactions to the loss of one round whom their affection centres. The mournful outpouring of Nanda in the Saundara-nanda betrays the remorse resulting from a rash act, committed under compulsion. Those of Sundari, his wife, bespeak the frustration of a young woman whose conjugal life going to be blighted.

| Preface | 5 | |

| Introduction

| 9 | |

| Section I | | |

| Gambler's Lament

| 3 | |

| Section II | RAMAYANA | |

| Laments of Dasaratha | 7 | |

| Laments of Rama | 12 | |

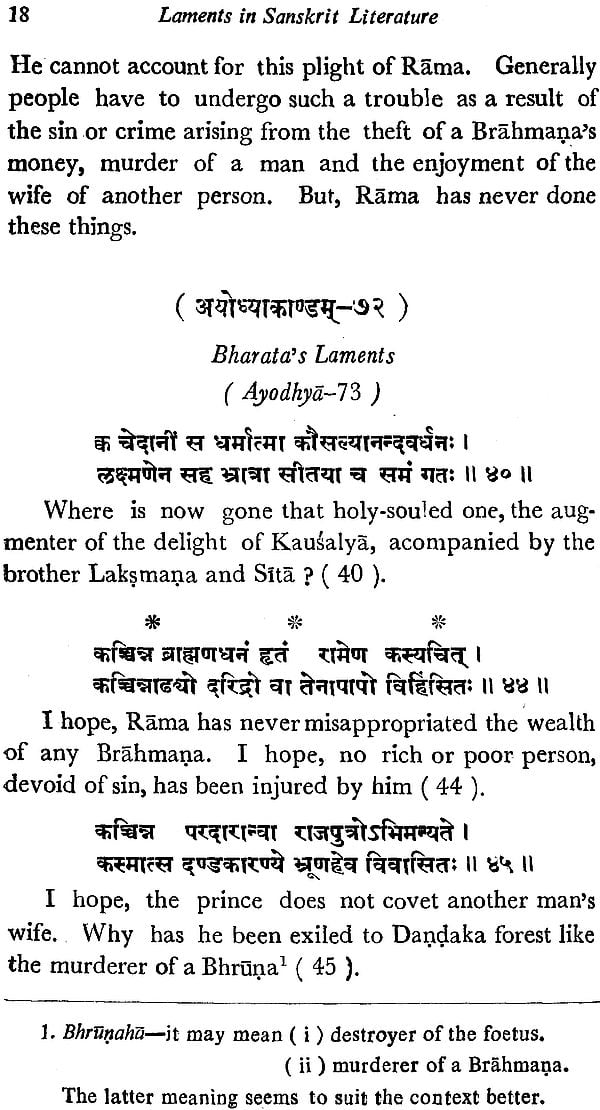

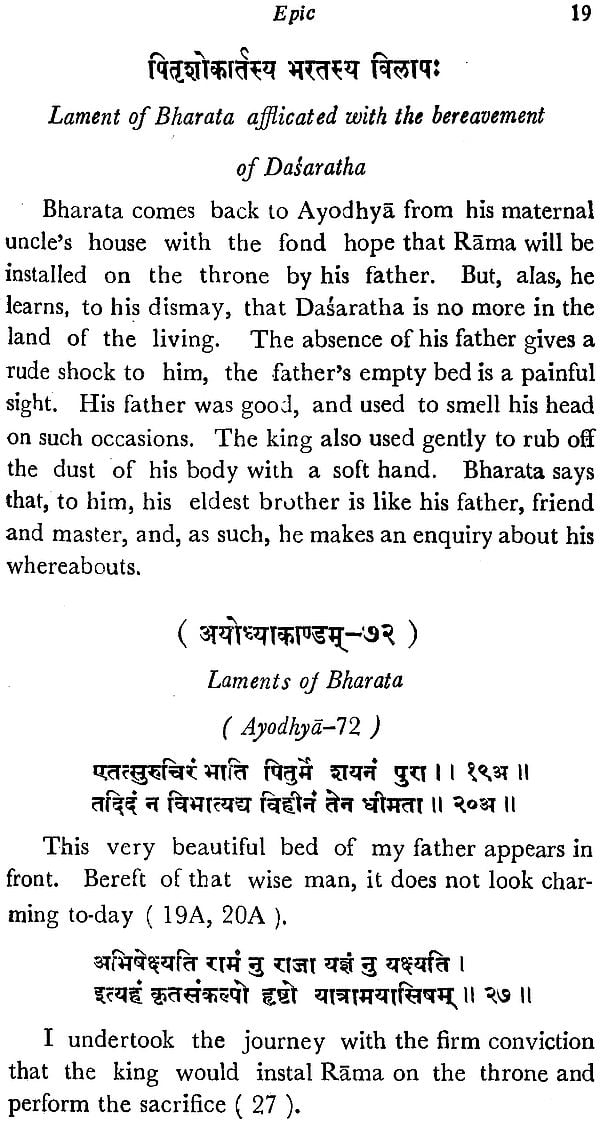

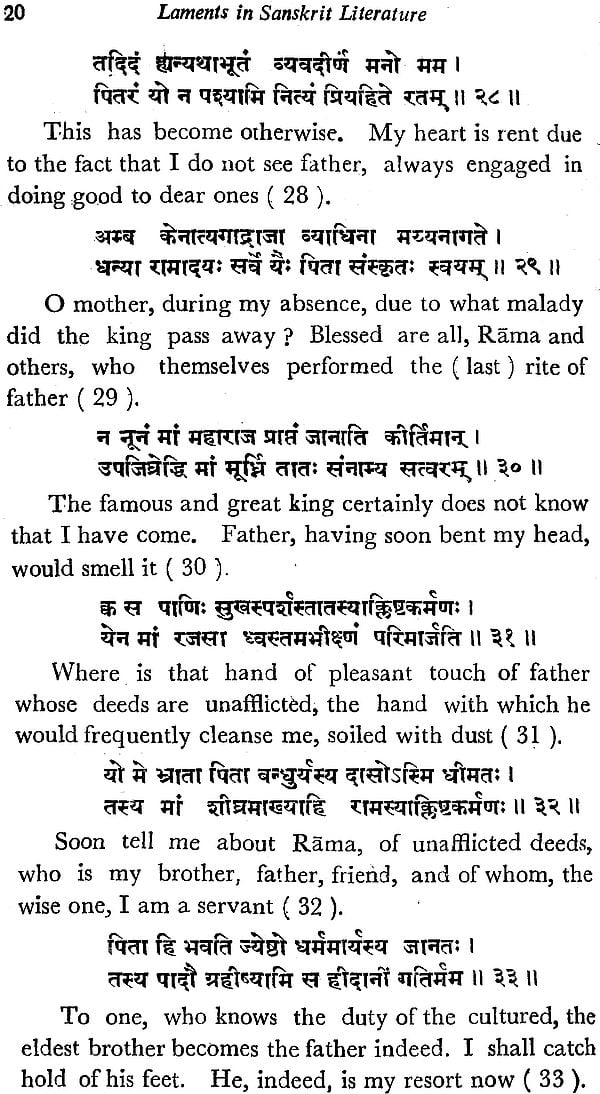

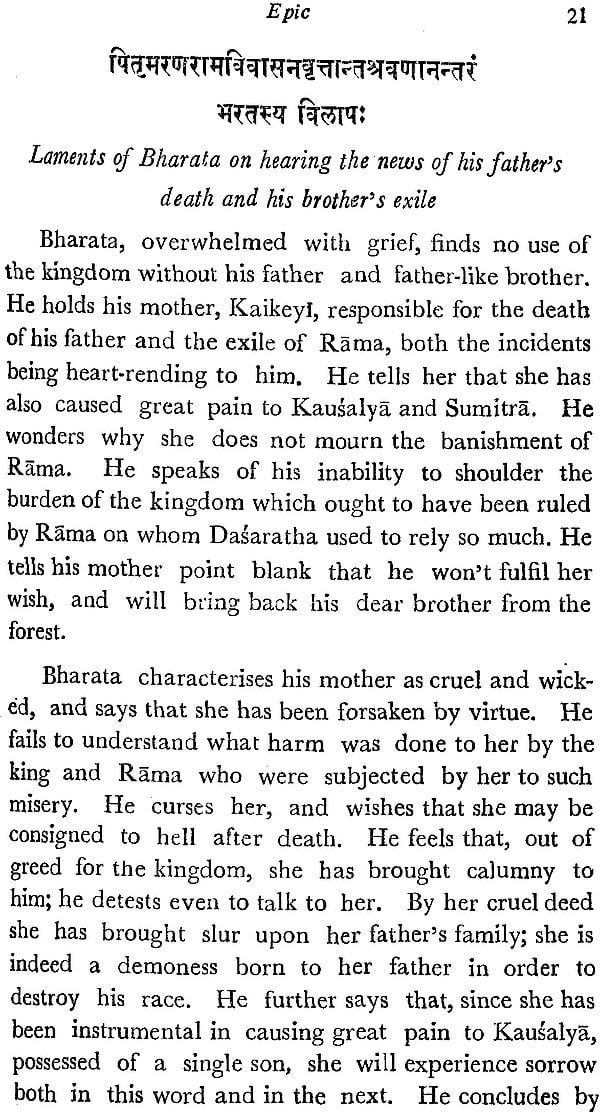

| Laments of Bharata | 17 | |

| Laments of Hanumat | 27 | |

| Laments of Citizens | 34 | |

| Laments of Andhamuni | 35 | |

| Laments of Ravana | 38 | |

| Laments of Surpunakha | 43 | |

| Laments of Kausalya | 46 | |

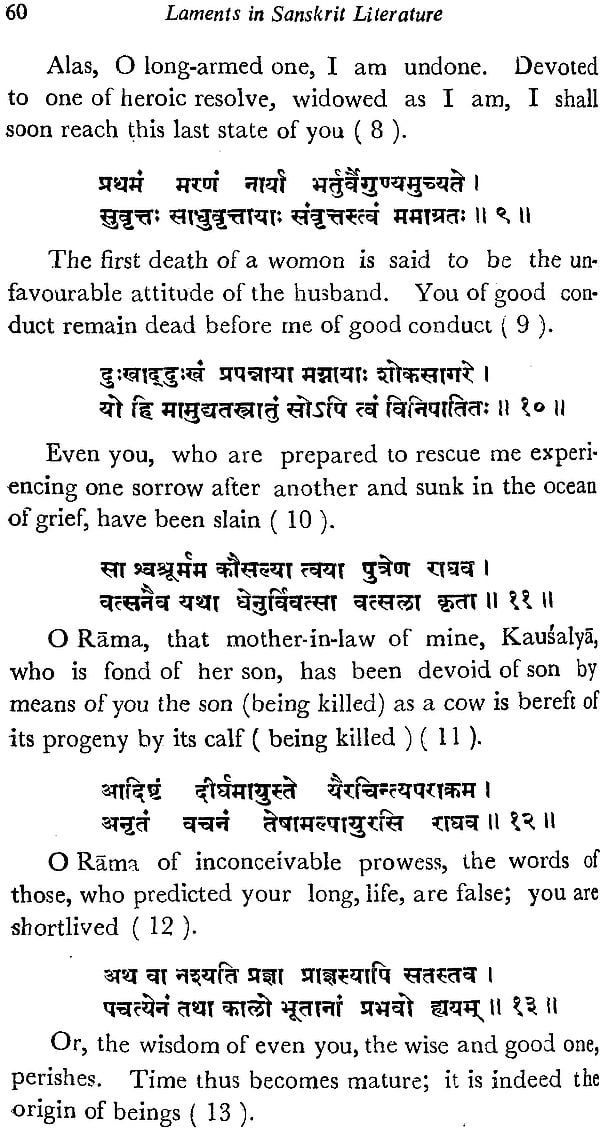

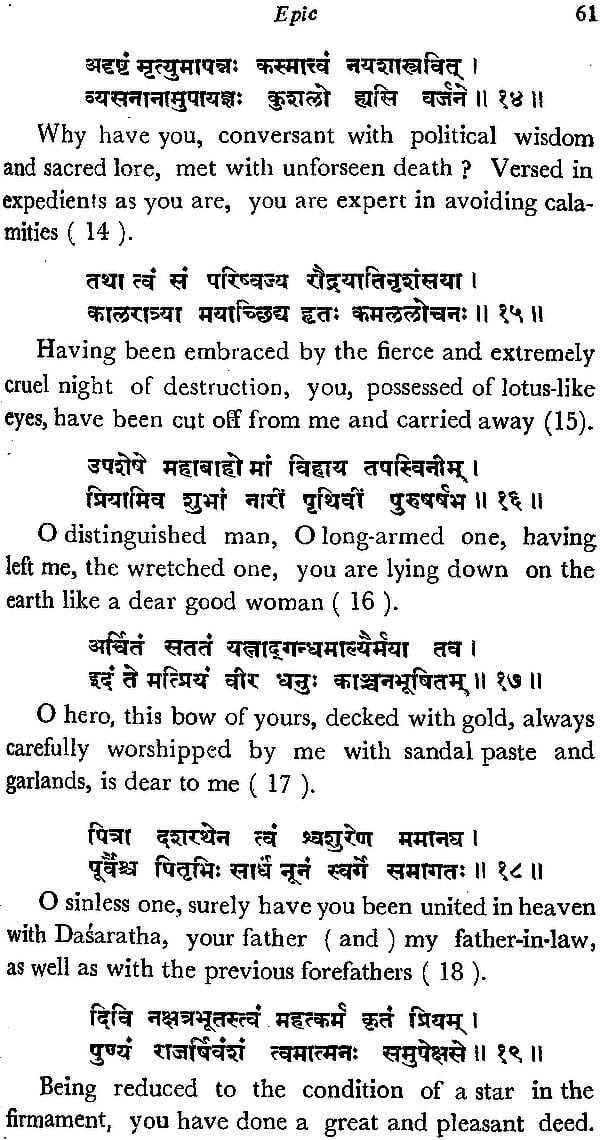

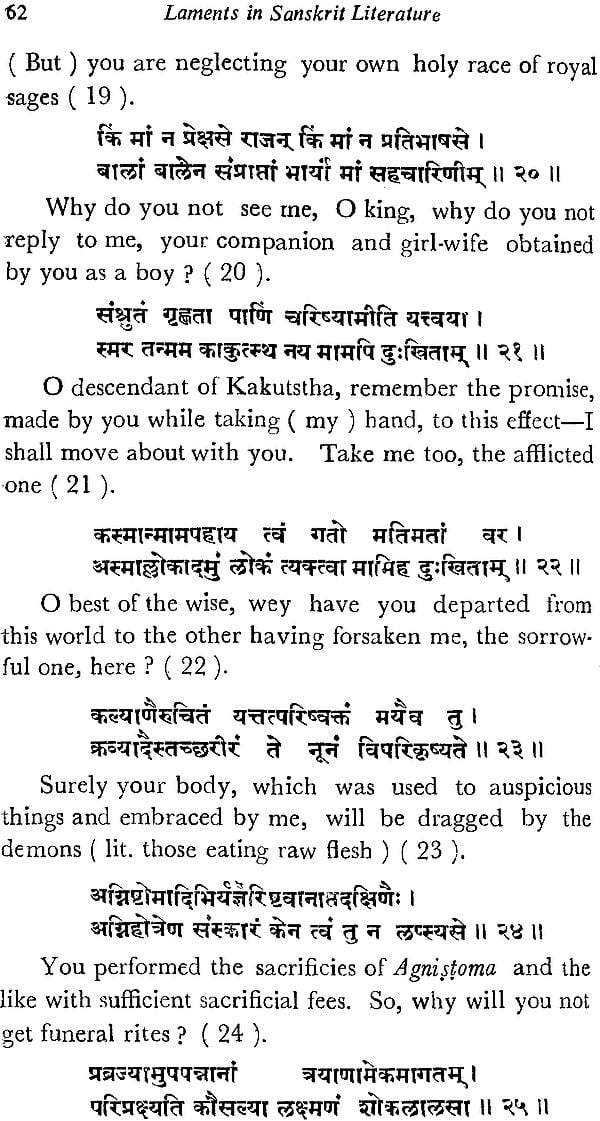

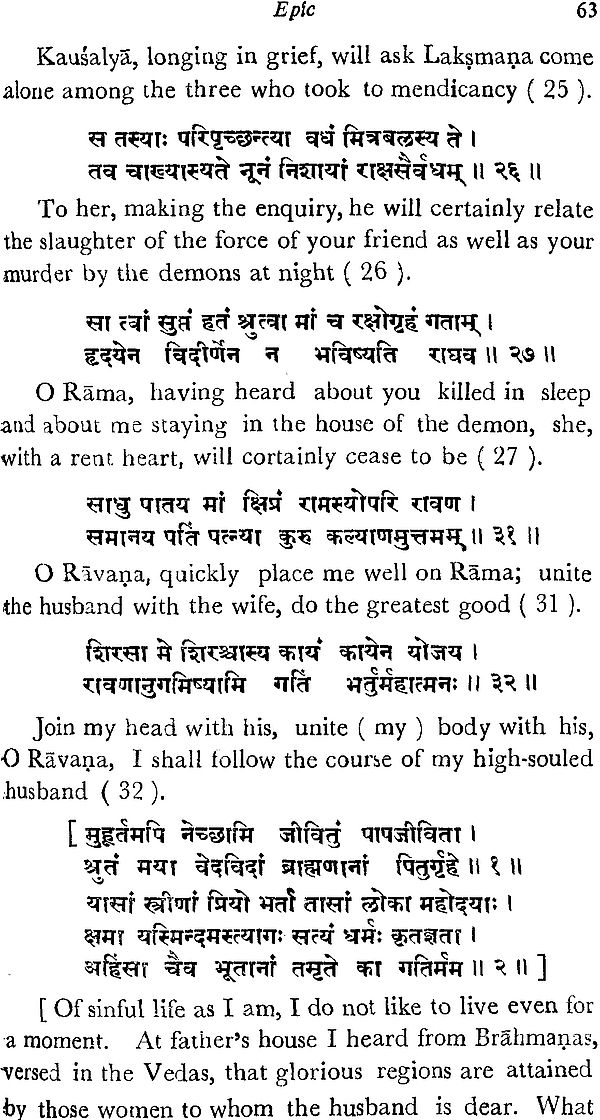

| Laments of Sita | 58 | |

| Laments of Tara | 71 | |

| Laments of ladies of the harem

| 76 | |

| | ||

| Laments of Dhrtarastra | 78 | |

| Laments of Duryodhana | 103 | |

| Laments of Yudhisthira | 110 | |

| Laments of Arjuna | 114 | |

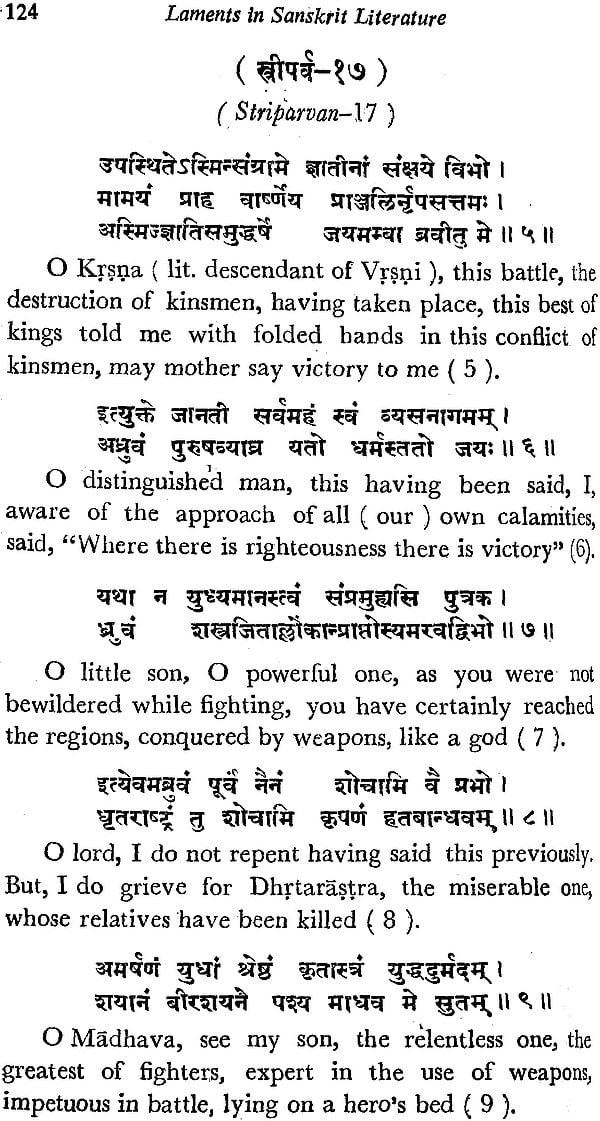

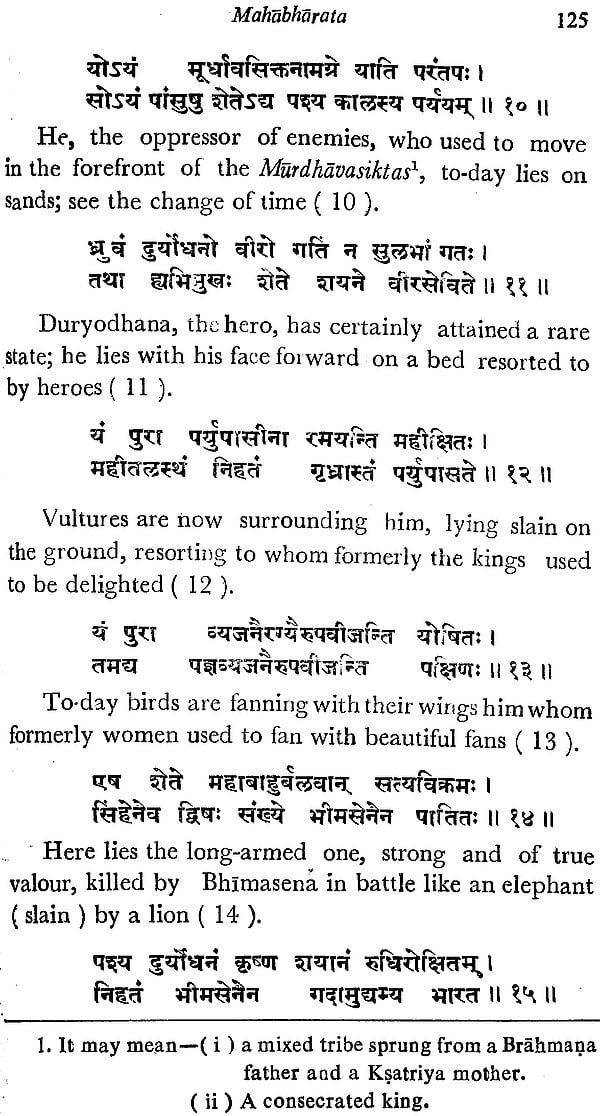

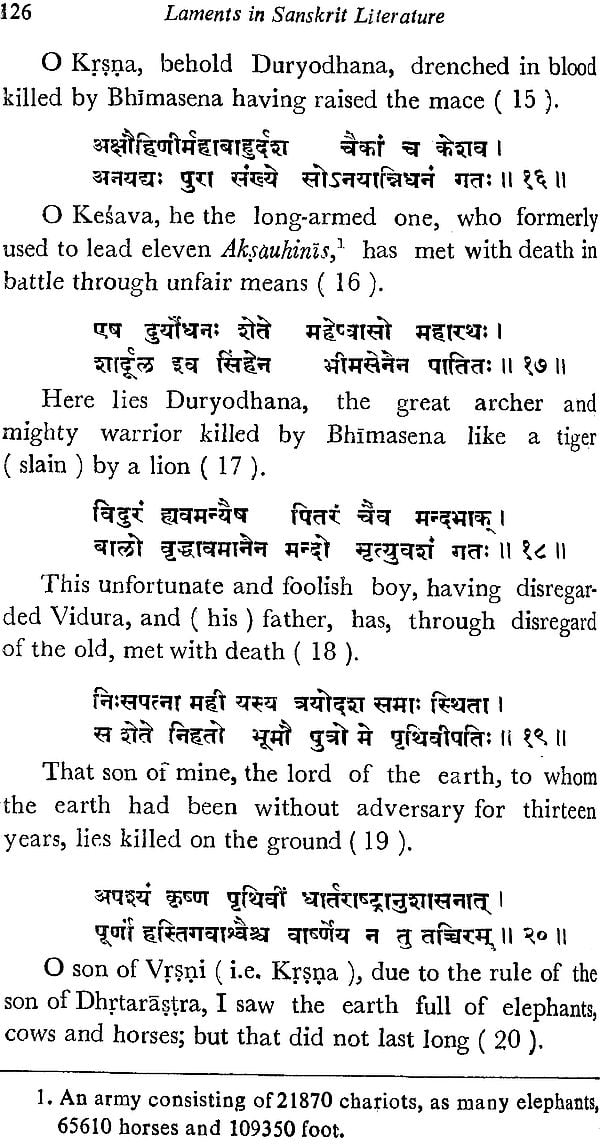

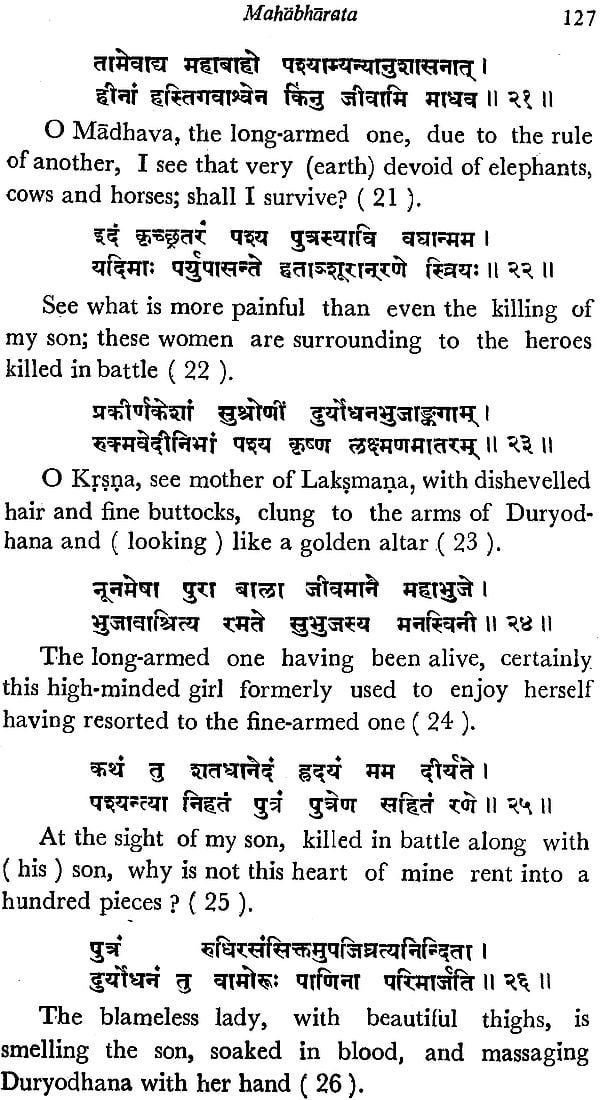

| Laments of Gandhari | 119 | |

| Laments of Damayanti

| 165 | |

| Section III | | |

| Laments of cowherdesses

| 169 | |

| Section IV | | |

| Laments of Suddhodana | 177 | |

| Laments of Nanda | 179 | |

| Laments of Gautami | 188 | |

| Laments of Yasodhara | 190 | |

| Laments of Sundari | 195 | |

| Laments of Dusyanta | 197 | |

| Laments of Aja | 201 | |

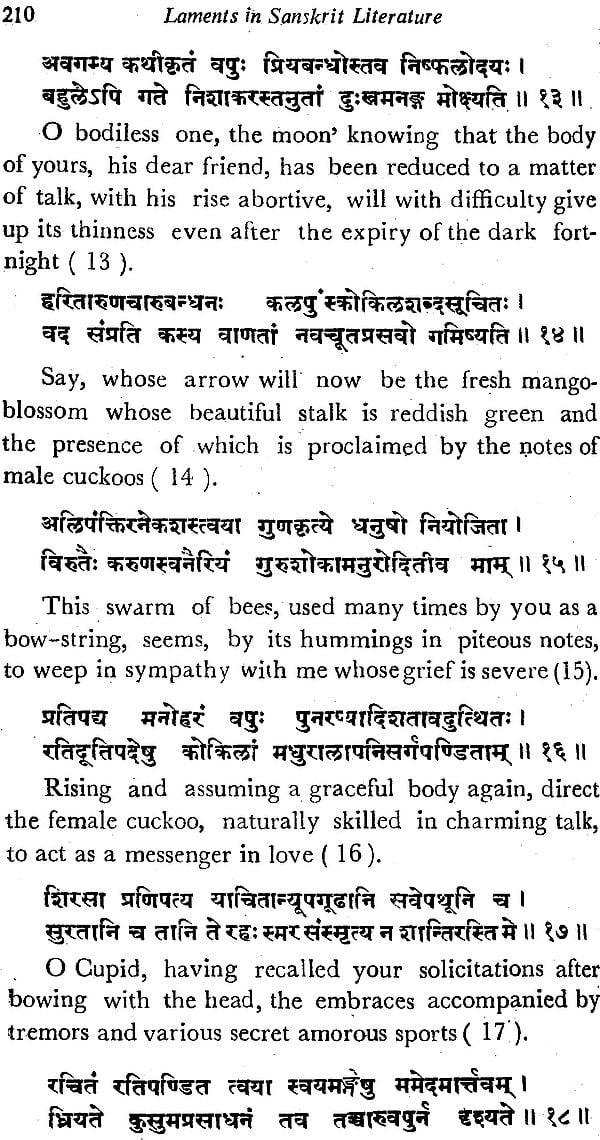

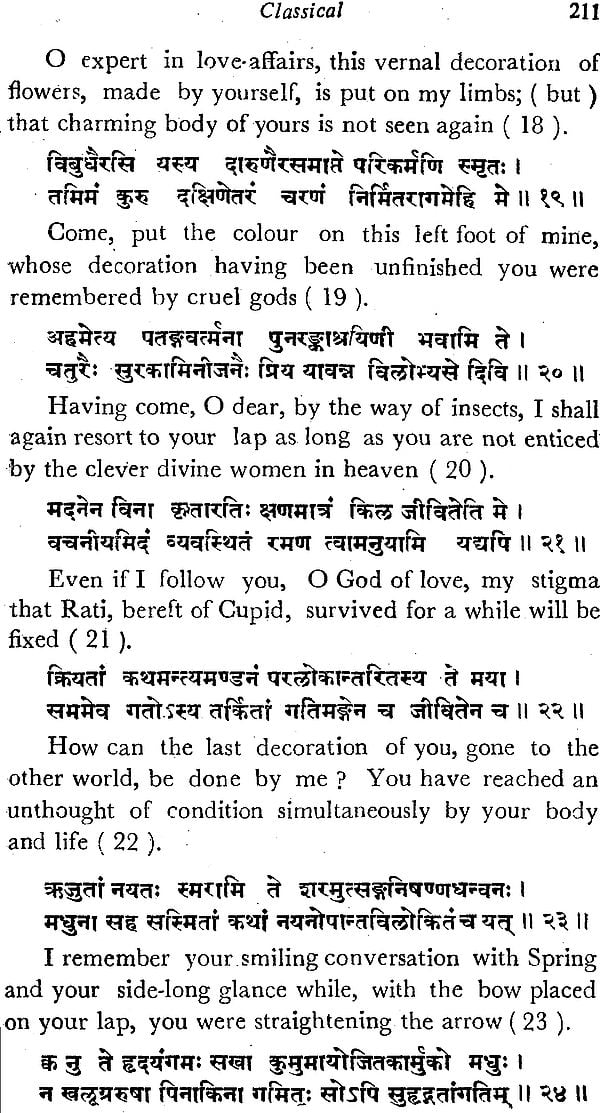

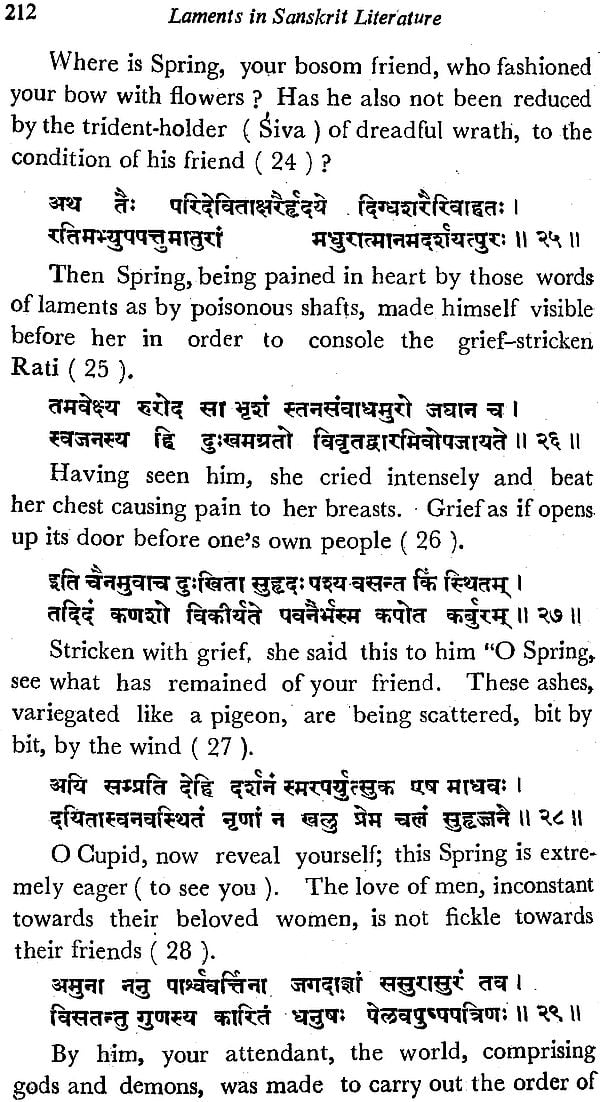

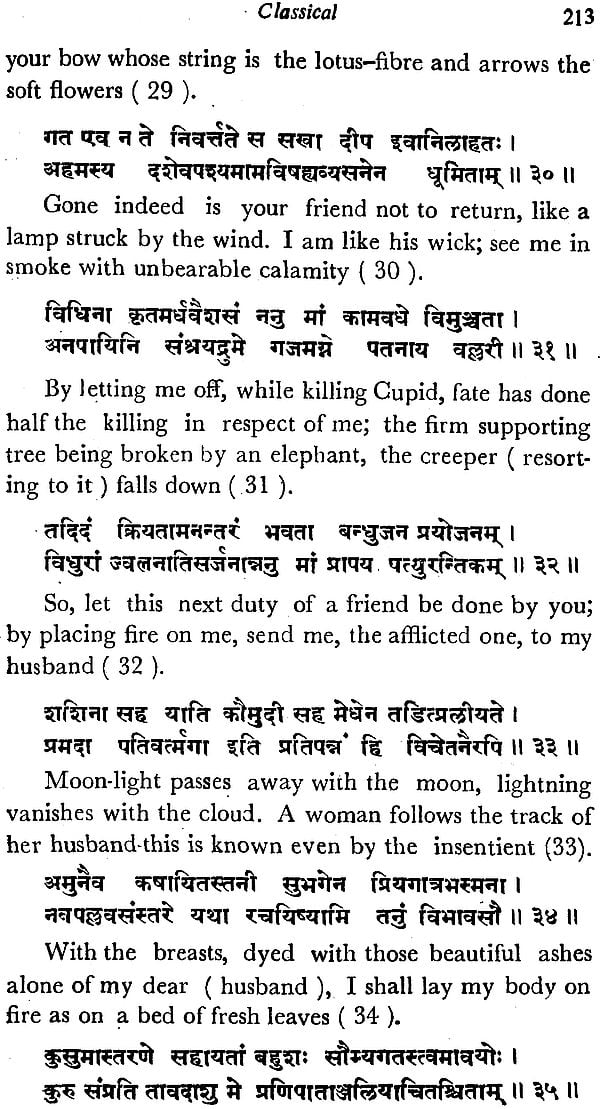

| Laments of Rati | 207 | |

| Laments of Rama | 214 | |

| Laments of Carudatta | 217 | |

| Laments of Mahasveta | 221 | |

| Laments of the Swan

| 223 | |

| Appendix I | 227 | |

| Appendix II | 232 | |

| Appendix III | 235 | |

Click Here for More Books Relating to Sanskrit Literature