Masterpieces of Indian Literature and Art (Tears of Kannaki : Annals and Iconology of the 'Cilappatikaram')

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAE553 |

| Author: | R.K.K. Rajarajan |

| Publisher: | Sharada Publishing House, Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2016 |

| ISBN: | 9789383221141 |

| Pages: | 508 (Throughout Color and B/w Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.00 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 1.62 kg |

Book Description

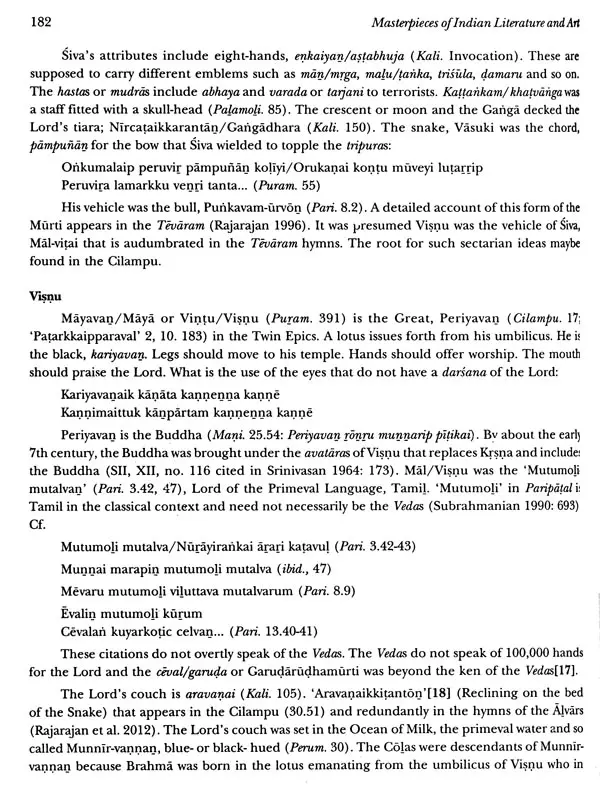

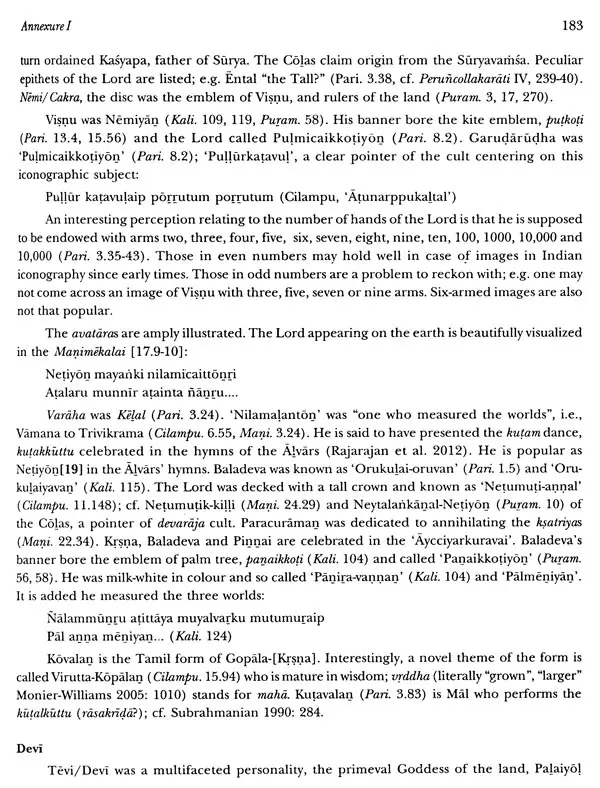

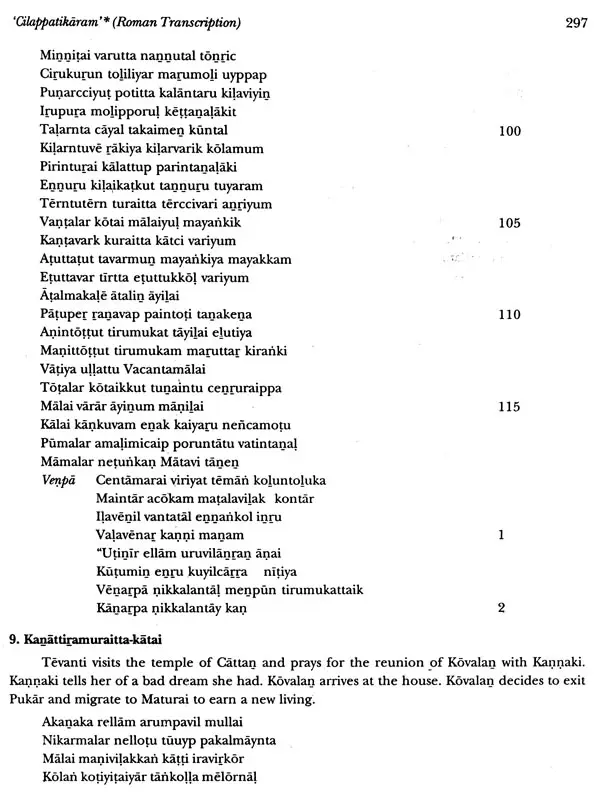

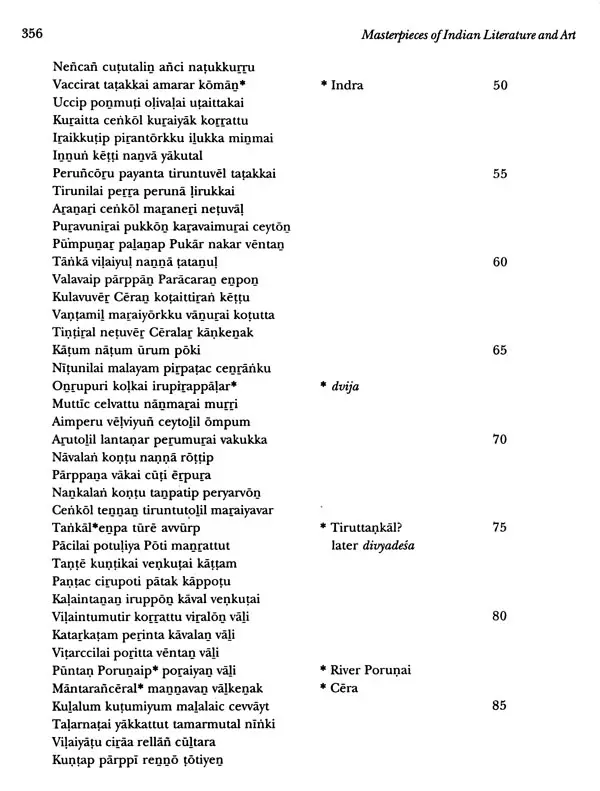

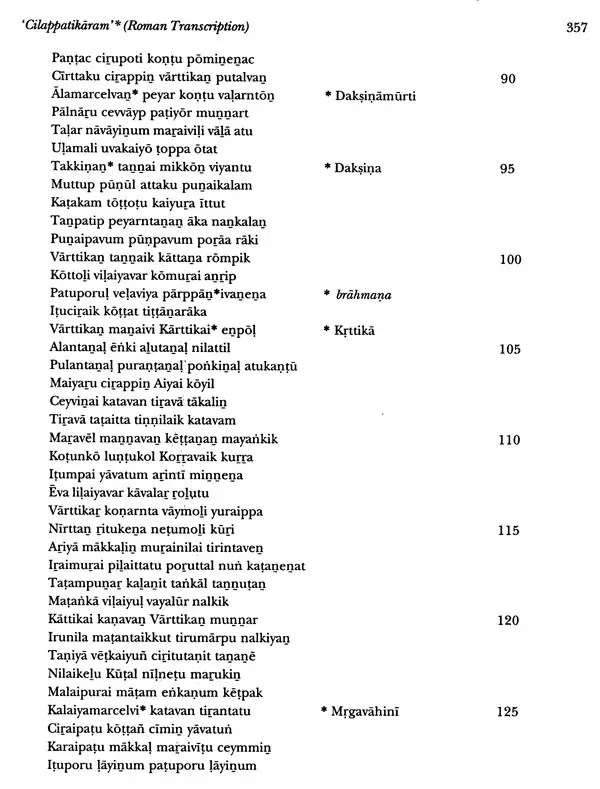

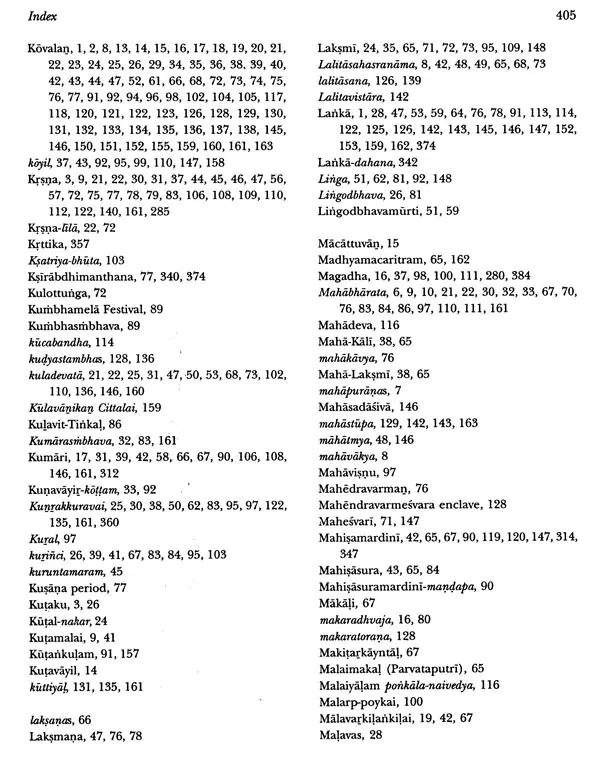

Designed in five nodal chapters, the book in two parts includes two annexure-s, glossary, bibliography (Part I), and Roman transcription of the Cilappatikaram followed by a comprehensive index (Part II), prepared by the publisher. Part I presents a copious picture of the following aspects:

Introduction dealing with formal details and date of the epic

Enumeration of the sequence of mythology of Kannaki

Iconography as may be summarized from each chapter (kataz) Iconology of ‘Kannaki and the Cilappatikar, amevents Two annexure-s dealing with 'religious imagery and architecture in Classical Tamil Literature' with special reference to Kalittokai and Manimekalai

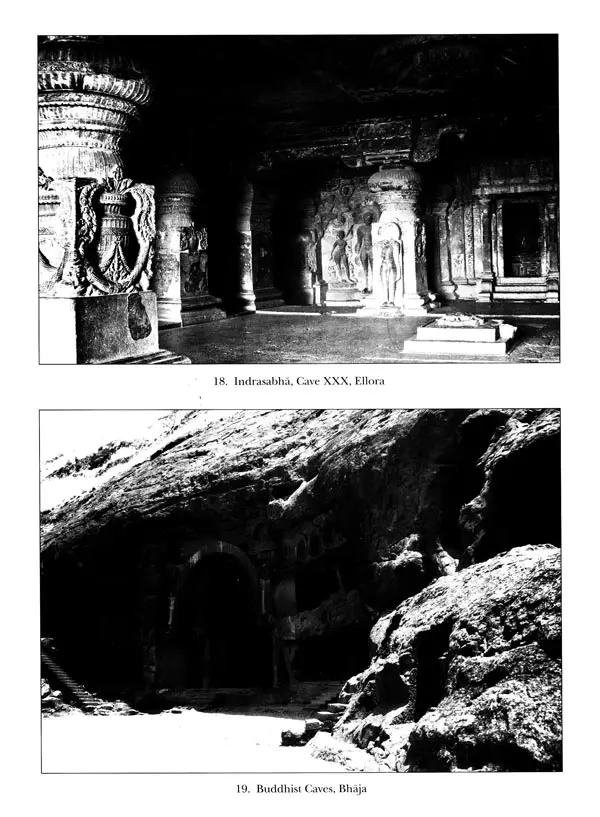

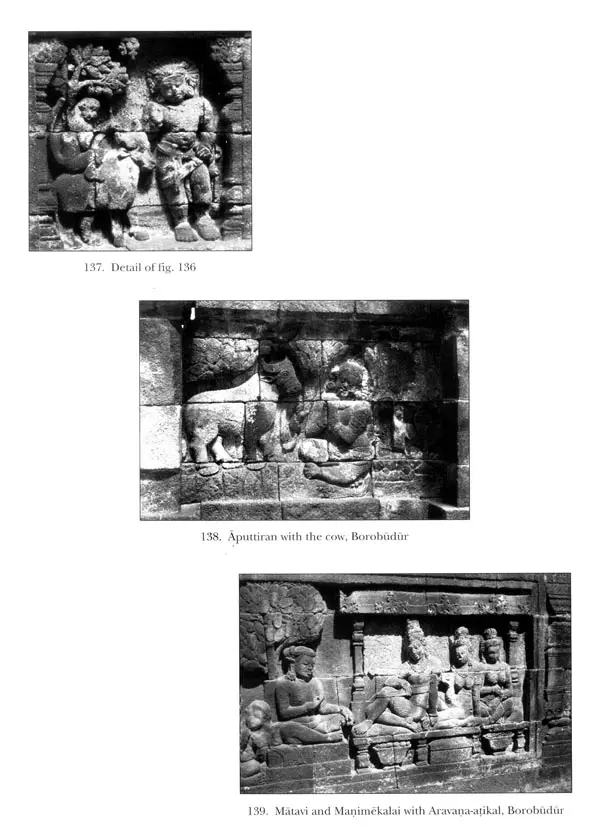

However, the main work is discussed in chapters III-V. For illustrations the author had done fieldwork from Kotumkallur in Kerala through Early Cola in Tamilnadu to Sri Lanka and Prambanan in Java.

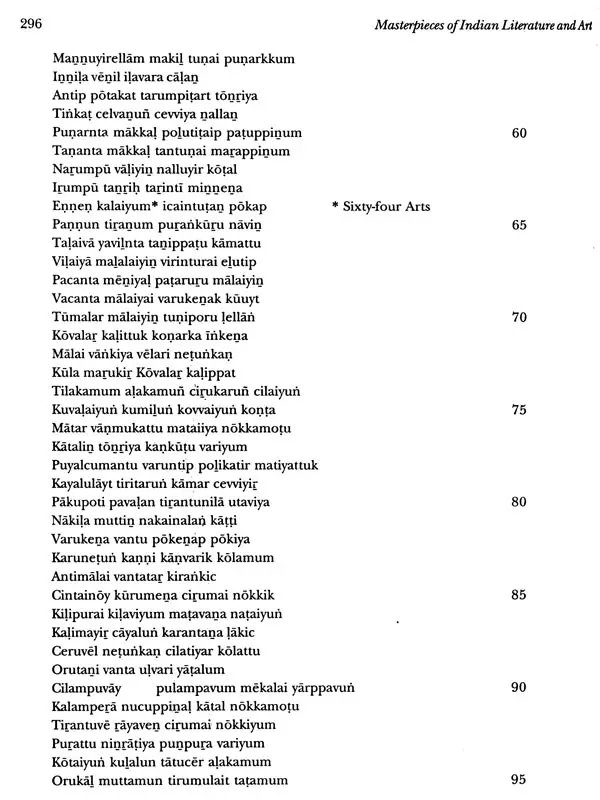

Part II of the book presents the epic in Roman transcription.

This part is evidenced by telegraphic notes within the format of the text.

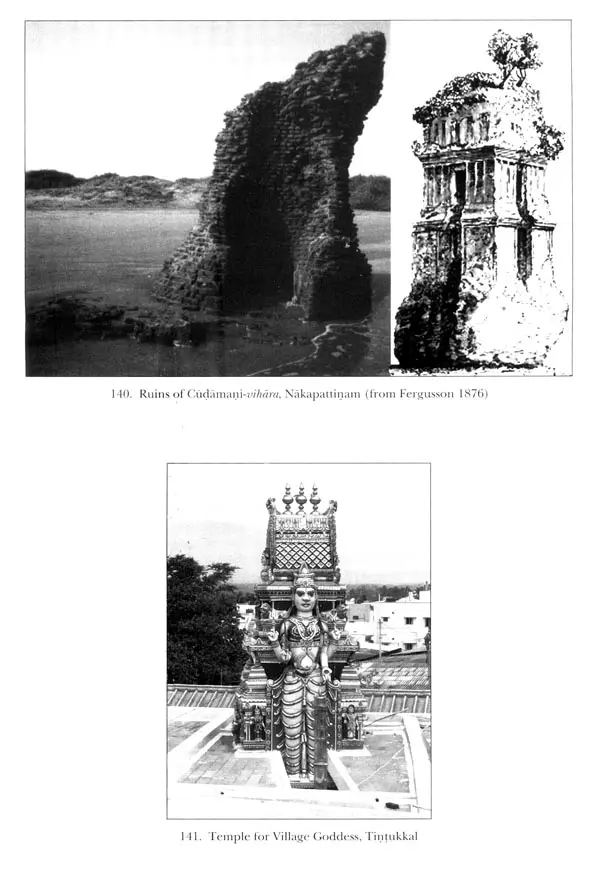

More than 140 photographic samples are presented to bring to our eyes the events that took place 2,000 years ago.

He had his basic studies in Madurai Kamaraj University and his M.Phil. & Ph.D. at the Tamil University, Thanjavur. He was post-doctoral fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Bonn) in the Free University (Berlin). He was on the teaching staff of the Eritrean Institute of Technology, Asmara and GandhigramRural University, Gandhigram for some time.

The author's Master of Philosophy thesis was on the art history Alakarkoyil temple (the historicaldivyadesa-Maliruncolai), and doctoral work on Nayaka architecture and iconography, published by the Sharada Publishing House (Delhi, 2006) in two volumes. His other publications includes Studies in Art History of India (ed. 2010), Rock-cut Model Shrines in Early Medieval Indian Art (2012), and Mindksi-SundareSvara: Tiruvilaiyatar Puranam in Letters, Design and Art (with Dr Jeyapriya, 2013).

However, the outstanding publications are in international journals published from Rome (East and West), Napoli (Annalidell' University did Napoli Orientale), Oslo (Act Orientalia) , Sheffield UK (Religions of South Asia), Berlin (Berliner Indologische Studied), Reinbek (Festschrift of Professor Helmut Nespital), South Asian Studies (Cambridge), The Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society (Bangalore), several conference proceedings and felicitation volumes.

Masterpieces of Indian Literature and Art

The Classical Phase:

'Tears of Kannaki' Annals and Iconology of 'Cilappatikaram'

It is almost a universal acclamation among scholars good at Tamil that the king of Tamil poets is Inanko-alikau, author of the Cilappatikaram. In fact the verbal meaning of the term, alanko is "prince". His epic is the subject-matter for intensive research by scholars from the east and west during the past century. It has been investigated from the point of language, literary criticism, epic qualities, sociology, anthropology, and so on. The present attempt is novel in dimension and brings out the unique features of Tamil Culture with reference to architecture and iconography or iconology. The subject is viewed in its pan-Indian setting, and singles out the idioms that are individualistic of Tamil. The book is in five chapters and annexure-s designed to trace the annals of the epic, its iconological dimensions and the representations of the theme in the sculptural art of South and Southeast Asia. No scholar had thought in these lines so far. I congratulate Dr Rajarajan for his new vision and interpretations. For example, he says how the yavanas were sentries watching the forts of the Tamil metropolises of those times and how few of them had mingled with the local population as pawn-brokers or goldsmiths. The identification of the arch-villain, the porkolla1) (goldsmith) with a Jew-yavana is a bold thesis that may invite debate from the scholarly circle. The author humorously adds the yavanas came with economy wine and returned with expensive pepper! What was purchased in India was sold ten or fifteen time higher than the original price in Athens and Rome or Constantinople, and other European mercantile cities. Europe would have starved had not ships laden with spices (first noted in the 'Old Testament of the Bible') from Pandya-Keralaputra hills moved in the Indian Ocean. Sure, the Cilappatikaram is a subject-matter for Indian Ocean studies.

To say briefly the first books is concerned with the following thematic segments and investigates the subject deeply:

A brief introduction to the history of the Tamil Twin Epics; Annals of the Cilappatikaram for a better visualization of the arguments;

Iconographical notes that are stored in the epic, chapter (i.e. katai) by chapter;

Consolidated iconological themes with particular reference to Devi-Vettuvavari', Mayon Visnu-Ayccayarkuravai', and Murukan-Kunrakkuravai': the Jain-Buddhist arauor "Guardians of Cosmic Peace" setting the roots;

An exhaustive picture of the iconology of Kannaki-Pattini that is duly illustrated from the arts of Tamilnadu (e.g. the Pumpukar Kalaikkutam); Kerala (Kotunkallur Vancaikkauam), Lanai (Mullaittivu), Cavakam (the mahastupa of Borobudur in Java), and recent additions on the Marina Beach in Chennai; needless to say these are novelties of the book;

The conclusion in poetic diction is to be chewed and digested;

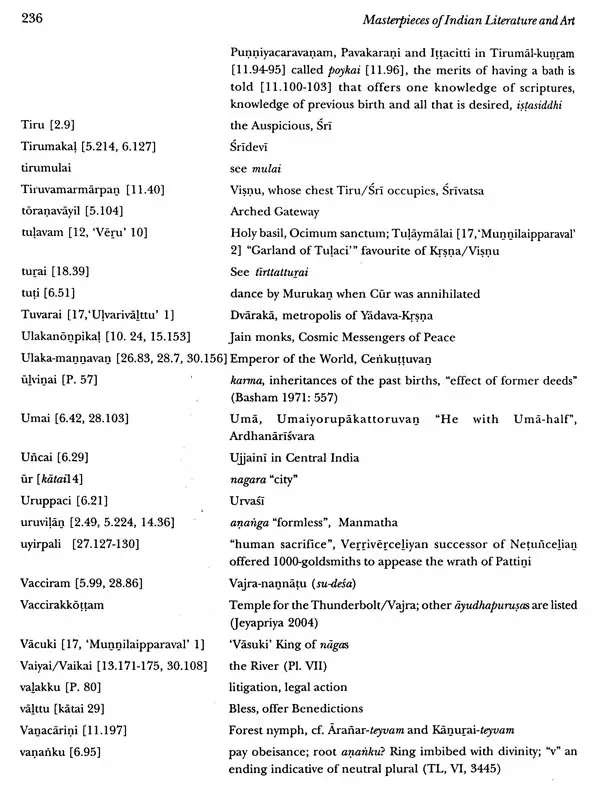

The annexure-s on the religious setting of 'Pattuppattu', 'Kalittokai' and 'Manimekalai' were papers presented in conferences organized by the Gandhigram Rural University; Glossary of Sanskrit and Tamil words with elaborate notes in English;

Rich bibliotheca "masterminds of the past" that is the result of research in the Institute fur Indiscreet Philology und Kunsgeschichteder Freien Universitat Berlin, Germany as Alexander von Humboldt post-doctoral fellow; hats off to professors AJ. Gail, Helmut Nespital, Gerd J.R. Mevissen, and Jurgen Nuess; The illustrations from South and Southeast Asian art bring to our eyes the events of what took place some 2,000 years ago!

An outstanding contribution is that the entire Cilappaikaram is recast in Roman script. Now non-Tamil scholars from any part of the globe may read the classic with his lips and estimate the cultural value of the epic in the global context of "peace and harmony". This is the nodal message of the Cilappatikaram as the lecture of the penultimate part of the epic would adumbrate.

Dr Rajarajan is a field-based scholar that is amply proved by the illustrations added. Within a short range of six months after I took charge as Vice Chancellor of the Gandhigram Rural University reprints of several articles were given to me; and these are published from Oslo, Naples and Sheffield (UK), and few from the QJMS (Bangalore), an internationally circulated homeland journal; and few more after joining the JNU.

The translations, doctoral theses, monographs and research articles written on the Tamil epics are myriad. Scholars from the Far East to the western hemisphere, especially Ceylonese seeking asylum in the US Universities (Obeyesekere 1984) have delved into the epics to cull out the symbolism; each trying to identify Kannaki if not Kovalan either in the Semitic block or the micro-island, Imam (Pattimappalai 191). In spite of all these efforts it continues to be a living problem for investigation, and research continues. The aim of the present study is to examine the Cilappatikaram, occasionally shedding light on Manimekalai and the classical Cankam corpus from the point of religious iconography with glimpses on societal orientation that may call "iconology". It is not concerned with literary excellence, linguistics or prosody. Scarce attention has been paid on iconography in few pioneering articles published in international journals from Copenhagen/Oslo: Act Orientalia, Berlin: Berliner Indologische Studied, London: Journal of the Ruyal Asiatic Society and Journal on the Institute on Asian Studies. These early studies on the iconography of the epics mainly centers on Cilappatikaram and the cult of the Pattini Goddess, Kannaki. She came to be identified with Minacs through Tatatakai, the trio called Ankayarkanni, one with fish-like darting eyes that do not wink (Brown 1947; Hudson 1993). Few studies have thrown light on dance of the gods (Kalidos 1996, 1999; Rajarajan 2000; Jeyapriya 2004).

Tamil scholars are interested in the literary excellence of the Twin Epics and few scholars of the Tamil University of Thanjavur have attended to the religious setting, philosophies, temples, the temple arts, iconography and architecture. In this respect the most deserving specialist is Prof. S.N. Kandasamy, who did his doctoral thesis in the Annamalai University relating to the philosophies of the Manimekalai [2]. He is a master that could work in Tamil, Sanskrit, and Prakrt. Even if no archaeological "monument of the Cankam or post-Cankam period has come to light, the iconographical and architectural potentialities have been ascertained in the researches of Raju Kalidos (Act Orientalia, Denmark) et al. [3]. The aim of the present' study is to present a comprehensive picture of the iconographical glimpses epitomized in the Cilappatikaram. Few surviving relics of the cult of Kannaki, supposed to be frozen remnants of her temples and the iconographical forms of the historical times that could be dated since the seventh century discussed. No temple of Kannaki or visual narratives of Cilappatikaram and Manimekalai seem to survive in Tamilnadu that could be dated in the pre- seventh century CE Few monuments identified with the fossils of Kannaki temples from Nakamalai "Snake Hill", Cimmakkal ‘Lion Stone" (East Velvety, Maturai), Kampam hills (cf. ekampam "mono- pillar", Venvelankunru of Cilampu. 29.13), and Kotunkallur (city of harsh stone) in Kerala, and the modern in Pukar (no entry [to enemies]) are examined.

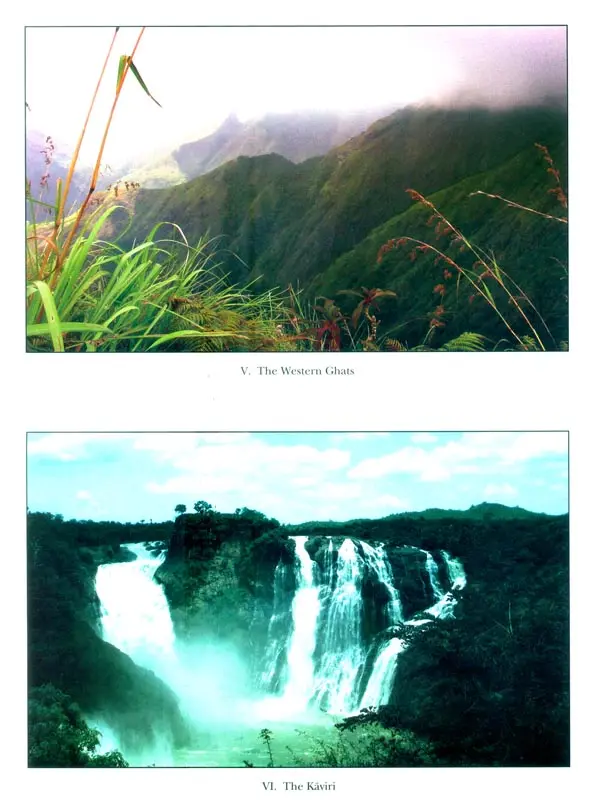

Hail the Pandya! Let the Primeval Family live long in Maturai because of the torrential water that flows in the River Vaiyai (presumably the tears of Kannaki that she shed in the Western Hills) [1].

Hail and Hail the Pandya and the Maturai country, and the Vaiyai[2]".

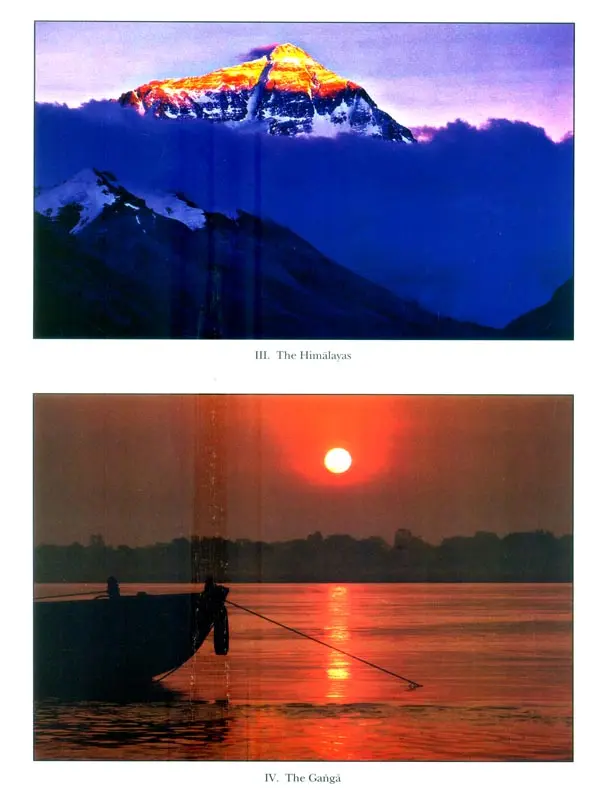

Pukar-born in the Cola country, Kannaki with her husband Kovalai.[3] migrated to the Pandyan world to earn a living, having lost their wealth to the courtesan Matavi, The Chaste Maid roamed around the Cera country due to the untimely death of Kovalan, and the blind justice of Netunceliyan. Interestingly, Kannaki is addressed 'Nirvar-kannai' "Dear, shedding water in Eyes" [20.48]; suggesting the root of her name is from Pattini, the Chaste was deified by the hill-folk, the Kunrakkuravar. Verriverceliyan of Koraki, successor of Netuficeliyan had offered 1,000 goldsmiths to appease the wrath of the Goddess (for Antiquity of Pandyas see 'Attachment'). The Cera King, Cenkuttuvan built a temple, consecrated her sculpted image with a stone brought from the Himalayas, and instituted an oriental festival. Kings of southern India and the distant eastern islands (Lanka, Svamabhumi or Cavakarrajava, and Yavana) are said to have celebrated the glory of the Goddess of Chastity and transported the cult to their respective countries.

The tears of Kannaki were shed on two other occasions earlier. On hearing the unjust murder of Kovalan, she proceeds to the mortuary and weeps lifting the corpse (Obeyesekere 1987: frontispiece). On that occasion Kovalan resurrects and consoles her not to weep. Lank adds:

Allalur rerate alluvia "in great distress she wept bitterly steeped in un surmountable grief' A Great Goddess, 'Perunteyvam' she could not bear the burden of misery, and wept bitterly:

The tears of Kannaki resulted in death of the Pandya and the destruction of his metropolis. The ethics of Valluvar would emphasize: "The tears of the unenduring miserables are the missiles that root out the wealths of those in power".

The above cited verses from the Cilampu guide us to understand the tears of Kannaki metaphorically flow in the Vaikai to fertilize the Maturai country. Reiterating the idea in a different mould, Lank says the tears of Vaikai flow torrentially that which could not be barricaded: Kannaki was wrathful toward the Pandya King because of the injustice done to her husband; and destroyed Maturai causing a conflagration. As a Goddess her wrath is appeased; and says she is the daughter of the Pandya because he was responsible for her apotheosis. She confers benedictions on all those that took part in the festival that Cenkuttuvan undertook. She not only blessed the Pandya but also the Cera, Cola, Kayavaku of Lanai, Karunatas et a1. and above all the poet, Lank who versified Kannaki's annals.

In Indian tradition it is a disgrace for the man to weep. Such a person is considered coward.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages