Mother Goddess Candi (Its Socio Ritual Impact On the Folk Life) - An Old Book

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG415 |

| Author: | Sibendu Manna |

| Publisher: | PUNTHI PUSTAK |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1993 |

| ISBN: | 8185094608 |

| Pages: | 330 (17 B/W Illustrations and 3 Maps) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 440 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

The phenomenon of emergence and spread of the cult of the Mother Goddess is regarded as one of the basic elements in the domain of the indigenous religious belief-patterns of India. Since its origin in the prehistoric times the Cult of the Mother Goddess passed through a continuous process of development and change conditioned by the nature and extent of the socio-religious spheres of the region concerned. Thus a close marriage of indigenous and modern thoughts and ideas has been effectively performed within the Mother Goddess Cult.

In the present study on the Cult of Candi, Dr. Sibendu Manna has taken up a broad-based principle to highlight the thought and action patterns of the people amongst whose midst Candi has emerged and developed through the ages. Dr. Manna has conducted painstaking field work through the adoption of different categorical methods of social science research, in a number of villages in West Bengal to examine what are now going on actually in the rural setting.

About the Author

Dr. Sibendu Manna Born: 1940

1973: Passed M.A. Examination in Bengali Language & Literature from Rabindra Bharati University.

1978: Obtained M.A. degree in Museology (with Anthropology and Archaeology as combination subjects) from the University of Calcutta. 1986: Passed B. Ed. examination from the University of Calcutta.

1991: Ph. D. (Arts) degree conferred by the University of Calcutta.

Dr. Manna, the author of this book is an enthusiastic investigator in Archaeology, Cultural Anthropology and Folklore. He has travelled widely over the different parts of south-western Bengal for collecting data on the subjects cited above, and published the results of his investigation in several articles and essays, which contain different features of Bengali Folk Culture, Folk Arts & Crafts, Archaeology etc.

As Curator, he has served 'Ananda Niketan Kirtishala' (Rural Museum on Archaeology and Folk Art & Craft). He is now working in a substantive post at Garbalia Rakhal Chandra Manna Institution (Bengali Medium School with Secondary and Higher Secondary Units), Howrah.

Life Member: Academy of Folklore, Calcutta; Bengal Library Association, Calcutta.

Preface

There is a proverb in Bengali, which means that-Where the scholars (Pandits) dare to go, there the idiot jumps such is the case of mine.

To undertake an inter-disciplinary research project like the present one, is not an easy task, because it requires uninterrupted and in-depth studies of various allied subjects. But, unfortunately, I had been out of touch with the academic studies for more than twelve years. During that period, I only availed myself of the opportunity of going through the books in the different libraries. However, in the year 1968-'69, I came in association with some learned persons, who have knowledge and experience in the academic as well as field studies. Amongst them, the person who comes to my mind first is Dr. Dulal Choudhury, D. Phil., Director, Academy of Folklore, Calcutta. Others are Dr. Rebati Mohan Sarkar, Ph. D., D. Litt., Head Anthropology Department, Bangabasi College, Calcutta and Editor, "Man In India", Ranchi, and Sri Tarapada Santra, the famous folklorist, author and the founder of the rural museum "Ananda Niketan Kirtishala" at Nabasan, p.a. Bagnan, Howrah.

With their active help and inspiration, I have gained some new vision of life and practically, they have changed my thinkings and even life-style. Lastly, I got involved in this sort of 'heavy-weight' research work. I have coined the word 'heavy-weight' because against the background of the Indian History & Culture, it seems to me really a hard task, to narrate every facet, to throw light on the every contour line of a vast picture having heterogenous elements like the cult of a female deity Candi Though knowledge knows no bounds but my efforts must have some limitation, and I am quite aware of that fact-yet, I have tried my best to show what I have experienced during the field-studies, and to describe what I have found in the secondary sources. The methodology applied here is based on the knowledge of Anthropology and Folklore. Hence, I have gone through the MSS., Books and Journals on the subjects, namely, Anthropology, Folklore, History of Religion, Art & Archaeology, History of India, Bengali Language & Literature and Sanskrit scriptures. Moreover, I have travelled a vast tract of land and villages in West Bengal, in search of field-data. It would not have been possible if I had not got the proper 'fuel' (i.e. inspiration and guidance) from the persons like Sri Santra, Dr. Choudhury and Dr. Sarkar. They are all my "friends, philosophers and guides" in the truest sense. Here it also deserves special mention that Dr. Sarkar not only supervised my dissertation but also wrote the 'Foreward' of this small book.

Over and above, Dr. Probodh Kumar Bhowmick, D. Sc., Professor & Head, (now Retired), Anthropology Department, Calcutta University, has also extended his hands of co-operation towards me on various occasions.

I convey my gratitude to all these learned scholars, whom I venerate and adore from the core of my heart.

During my studies and research, valuable suggestions were offered by Dr. Kalyan Kumar Ganguli, Ex-Bageswari Professor, Department of Ancient Indian History & Culture, Calcutta University, Dr. Somnath Mukherjee, Ph. D., Government College of Art & Craft, Calcutta, Dr. Suhrid Kumar Bhowmick, Ph. D., Department of Bengali, Uluberia College, Howrah, Dr. Pasupati Mahato, Ph. D., Anthropological Survey of India, Calcutta, Dr. Sabita Ranjan Sarkar, Ph. D., Keeper (now Retd.), Anthropology Section, Indian Museum, Calcutta, and Santosh Kumar Basu (now Deceased), Reader, Museology Department, Calcutta University.

In the present context, I would like to acknowledge my indebtedness to some of the well-wishers, friends and colleagues who have helped me in the study. Of them Sri Benoy Bhusan Roy, Librarian (now Retd.), Anthropology Department, Calcutta University, Dr. Atul Chandra Roy, Ph. D., Reader, Museology Department, Calcutta University, Sri Satyabrata Ghosal, M. Lib. Se., Librarian, Institute of Port Management, Calcutta, Sri Nirmalendu Manna, M.A., B. Corn., Garbalia Rakhal Chandra Manna Trust, Howrah, Sri Dasu Gopal Mukherjee, M.A., Lok Shiksha Parisad, Narendrapur R. K. Mission, Sri Ratan Kumar Das, Bengal Library Association, Calcutta, Sri Manoranjan Jana, B. Lib. Se., Rabindra Bharati University Library, Calcutta, Dr. Sushanta Kumar Roy, M.B.B.S., 'Niramay' Howrah, Sri Shuvendu Manna, B. Lib. Se., Howrah District Central Library, Sri Siddheswar Mandal, B.E., D.T.R.P. (Cal), Deputy Chief Engineer, Calcutta Improvement Trust, Sri Dulal Chandra Samanta, SAE, Liasion Officer (Municipality), West Bengal Housing Board, Calcutta, Dr. Kamal Kumar Kundu. Ph. D., Secretary Tamralipta Museum & Research Centre, Tamluk, Medinipur, and Safiulla Molla, M.A., Jagannathpur, (Munshirhat), Howrah, deserve special mention.

I am also indebted to Librarians and I wish to thank those at the National Library, Asiatic Society Library, Indian Statistical Institute Library, Indian Museum Library, Anthropological Survey of India Library, Rabindra Bharati University Library, (all are at Calcutta), including the Central Library, Departmental Libraries of Anthropology and Museology, Calcutta University.

During the field-studies, I got immense help from Dr. Rabindra Nath Samanta, D. Phil., Department of Bengali, Christians College, Bankura, Ms. Shyamali Ganguli (nee Ghosal), M.A., B. Lib. Se., Baidyabati, Hooghly, Sri Panchu Gopal Roy, Raspur,. Howrah, Sri Shishutosh Dhawa,.' M.A., Khakurdaha, Medinipur, Sri Niladri Mohan Sarkar, Rasa, Birbhum, Sri Jayanta Kumar Paul, M.A., Kaktiya, Medinipur, Sri Jitendra Nath Mishra, Babupara Maliara, Bankura, Sri Nani Gopal Bhattacharya, M.A., Bhadreswar, Hooghly, Sri Prabal Kanti Roy, Maldaha and Bhola Nath Chattopadhyaya, Candl Sevait Sangha, Makardaha, Howrah. Many Common villagers also helped me in various ways, during the field-work. I can not afford to forget the gratuitous services rendered by them in my project.

I shall be failing in my duty if I do not mention the roles of my most beloved parents (Late) Kanai Lall Manna and Smt. Bibha Bati Devi-their blessings and inspiration acted as the guiding force in this perilous journey. I shall also remember (Late) Madan Gopal Hazra and Smt. Anima Hazra for their substantial help. If my wife Smt. Chaitali and my daughters, namely, Km. Sharmistha, Km. Sohini and Km. Shrabanti had not shared my sweat, pain and tear with smiling. faces, I could not have achieved the goal.

I also convey my heartiest thanks to all of my colleagues and friends, specially, those at the Garbalia Rakhal Chandra Manna Institution, Howrah ; Sabuj Granthagar, Nijbalia, Howrah; Bengal Library Association, Calcutta and Academy of Folklore, Calcutta.

In fine, I am also grateful to Sri Shankar Kumar Bhattacharya of M/s. Punthi-Pustak, Calcutta, who took active pains to publish the thesis paper in the book form.

Foreword

The tradition-bound land and people of India are specifically characterized by the development of diversified beliefs and practices through time and these have gone a long way in moulding the overall perspective of the history of civilization of the country flourished in a chequered natural surroundings.

The phenomenon of emergence and spread of the cult of the Mother Goddess is regarded as one of the basic elements in the domain of the indigenous religious belief-patterns of India. Since its origin in the prehistoric times the Cult of the Mother Goddess passed through a continuous process of development and change conditioned by the nature and extent of the socio religious spheres of the region concerned. Thus a close marriage of indigenous and modern thoughts and ideas has been effectively performed within the Mother Goddess Cult.

Mother is the protector and saviour of the children-She is the person who keeps a constant and affectionate watch over Her children. The rural folk of India contribute wholeheartedly to this basic situation and the villagers here feel themselves safe and protected from untoward incidence in their day-to-day life if they are in a position to install a replica of the Mother Goddess in the village Shrine. The Mother Goddess is, therefore, seen not as a mere deity residing in the celestial world but as a guardian spirit having here abode in the hearts of the common people. It is for the well-being of the rural folk She rules over the rural setting-Her constant presence is indispensable in the villages.

The tutelary deity of the village, which is most of the time represented by the Mother Goddess, is characterized by the intermingling of variegated thought-patterns and it is for this reason close understanding of the Mother Goddess is essential in the attempt for knowing the life-philosophy of the people. The Mother Goddess, so to speak, has an all India spread and She has not only been processed in the background of the life-ways and thought-ways of the people but also She had adopted the regional sentiments as per character and contents of the regional philosophy.

The Mother Goddess, rooted to the pre-Vedic tradition, is at present seen to exert her influence in all the Puranic literature and, in a large extent, She is conspicuous in the age-old tradition of the Hindu philosophy. This long journey from the earlier pre-Vedic tradition to the latter Hindu tradition is characterized by the interacting patterns of varied thoughts and ideas belonging to both the traditions which are still seen to be reflected in the nature and extent of people's participation patterns and their looking into the different facets of propitiation as well as presence or .absence of service of the Brahmin priests in the deity's worship.

Candi is such a goddess who is seen to exert Her influence not only in the long time perspective but also in diversified forms with the performance of multifarious functions. Right from the tribal fold Candi is conspicuous to the domain of sanskritic scriptures through the indigenous cultural patterns as represented by the lower and untouchable caste groups holding lowest rung in the social ladder of the Hindu caste hierarchical system. As a natural consequence, Candi has been portrayed differently according to the thoughts and philosophy of the people concerned.

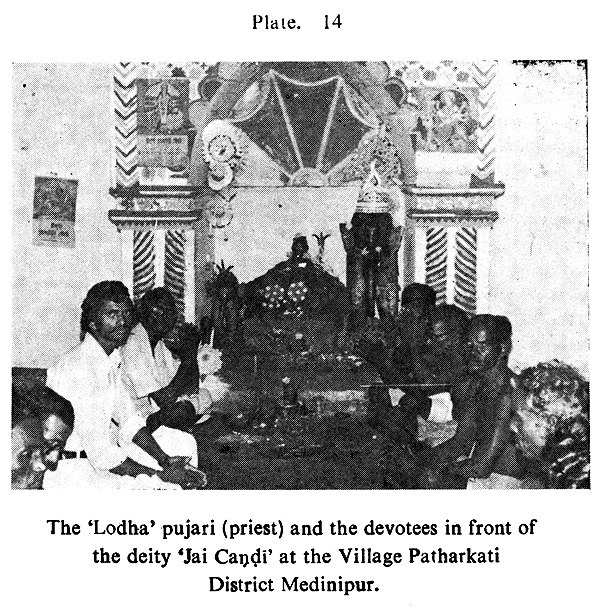

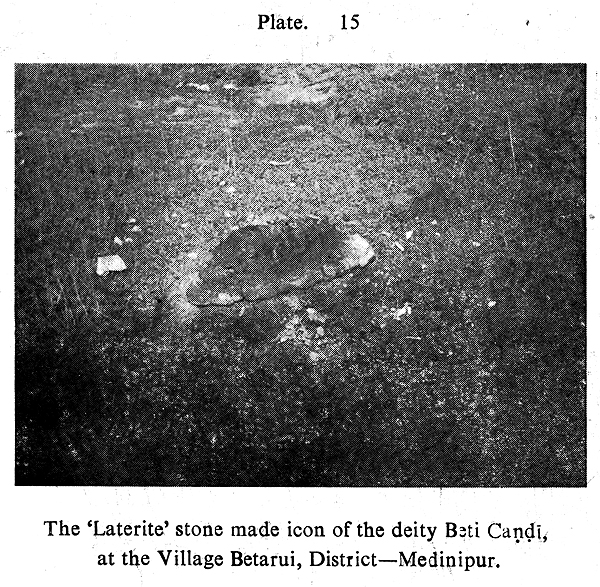

Thus the deity's representation starts from mere vermillion marked stone slabs and it ends in a finely built anthropomorphic forms characterized by the greater Hindu tradition. In some villages, She is worshipped under a tree in a comparatively lonely surrounding and in others, She is installed in a brick built temple in the very heart of the village. What is interesting to us here is that though the long spell intermixture of Great and Little traditions Candi presents herself in a variegated forms and multidimensional orientations. The socio-ritual matrix of the population perspectives closely attached to the cults of the deity of our concern can best be assessed if the different elements of t:e emergence, development, nature of propitiation and peoples' participation pattern are analysed in a systematic manner.

In the present study on the Cult of Candi, Dr. Sibendu Manna has taken up a broad-based principle to highlight the thought and action patterns of the people amongst whose midst Candi has emerged and development through the ages.

Much has been said, by the time, regarding the genesis and nature of the Mother Goddess and very little has so far been put forward about the integrated interacting patterns between the Mother Goddess and the people engaged in Her adoration.

Dr. Manna's line of study thus deviates from the stereotyped pattern; he had delved deep into the very recess of action-oriented situation of the Candi cult. The speciality of this study lies in the fact that it is perfectly based on the systematic mingling of the factual data collected both from recorded and field sources.

Besides supplying materials from different literary sources throughout the world on the origin, development and influence of the Mother Goddess.

Dr. Manna has conducted painstaking field work through the adoption of different categorical methods of social science research, in a number of villages in West Bengal to examine what are now going on actually in the rural setting.

Bengal has ever been presented herself as a fruitful field for the origin and development of various folk deities and in thousands of villages here the cult of Candi and the people have become an integrated whole for obvious reasons. The village studies thus conducted will depict the goddess Candi as a living embodiment controlling peoples' actions in every stage of their life which are evident from the running illustrations accommodated in the present treatise.

There is no doubt about the fact that Dr. Manna's two dimensional approach to highlight Candi cult proves itself efficient and effective.

This study is to be regarded not only as a valuable contribution to the existing knowledge on the subject concerned but it imparts factual guidance for the application of double-sided approach in the study of various folk deity-oriented cults influencing the life and philosophy of the people. The study .brings to light variegated social forces which help a lot in evaluating the traditional elements in rural setting in the broader perspective of Indian Civilization.

The worship of the Mother Goddess in India, from hoary past to the very recent period, represents a very significant part of Indian history and civilization. The cultural perspective of India is highly characterized by the multifarious activities of the cult of the Mother Goddess. It is so inextricably interwoven with the life and philosophy of the people that the overall exposition of the Indian tradition becomes impossible without paying considerable importance to this particular tradition-bound features of actions.

The cult of the Mother Goddess is not only related to the everyday life-activities of the people but it opens up a clear perspective of the horizon of traditions and culture of the country as a whole. In consequence of this, a close observance of the course of origin and development of the cult of Mother Goddess reveals a wonderful assimilation of broad- based heterogeneous elements, which, in the latter period have been united with each other by way forming a body of cognate legends and trend of theological and philosophical argumentation.

The archaeological perspective in India offers a broadbased scope for discovering the concrete evidences in favour of thorough existence of the cult in question during the remote period in the past. The objects recovered in the different ancient archaeological sites of Indian sub-continent are marked by the conspicuous practice of the cult throughout the prehistoric as well as historic period. The cult of the Mother Goddess was very much prevalent amongst the oldest known races like Semetic, Hellenic, Teutonic and Nordics alike, in the good old days (Dasgupta: 49: 1982). The cult in question penetrated so deeply into the life and activities of the people of India that it became the central theme of the folk philosophy of the country in question. It is traceable right from the Bronze Age with a conspicuous continuation through the various stages of Indian civilization upto the recent period. Various studies in this line reveal that with the march of time the cult of the Mother Goddess has spread throughout all the corners on the country with additions of new thoughts and ideas belonging to the indigenous cultural phases. Sometimes this phenomenon caused a great deal in inflicting changes in the cult itself. At times it witnessed conspicuous metamorphosis and thereby complications in the basic nature of the Cult.

The everknown ancient civilization in India, that flourished along the bank of the river Indus and its tributaries, is characterized by many ingenious devices both in technology and culture. The sites relating to these factors are more than eighty in number. This pro to-historic culture extended over a wide area up to Rupar in the east on the river Sutlej; to Lothal, a sea-port on the western coast in Saurashtra, and to Broach and Surat in the south. In contrast to this uniform riverine culture spreading over a large area along the river systems of the plains, we find innumerable cognate culture sites, namely, Quetta, Nal, Amri, Zhob, Kulli, Jhukar, Ali Murad, Pandi Wahi, Rana Ghundai, Sutkagen-dor, and so forth. Their culmination was at the three main centres, now known as, Chanhudaro and Mohenjodaro on the bank of the river Indus, and Harappa on the bank of river Rabi. Six and seven strata of antiquities have been unearthed respectively at Harappa and Mohenjodaro. They record the remarkable features of civilization in the soil of the Indian sub-continent since an early period of about the third millennium B.C. (Vats: 1958 : 110; Mookherjee: 1970 : 12; Pusalkar : 1951 : 169) . This civilization popularly known as "Indus Civilization" or sometimes called as "Harappan Culture". Thus India characteristically marks herself as one of the pioneers in the flourishing of the oldest civilization of the world and in this line she stands parallel to the countries like Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, Egypt and Assyria (Pusalkar: 1957: 169).

The artifacts found during the excavations at the protohistoric sites of Indus Valley belonging to Bronze Age would amply indicate the importance of the cult of the Mother Goddes in this country. Amongst the antiquities most prominently noticeable are the various kinds of female figurines, and it is ascertained that the Mother Goddess was an integral part of the 'Harappan' household cult, similar to that which prevailed in Western Asia and Palaeolithic Europe (James : 1957: 238). Further, the Nagarjunkonda in Southern India, has brought light on the remains of the Palaeolithic, Neolithic, and Chalcolithic periods. These artifacts also help to prove the ceaseless stream of the Mother Goddess in that area.

It is, no doubt, a very difficult task to state and prove as to where the worship of the Mother Goddess originated and flourished first, but it is obviously noticed that the cult in question was not only prevalent but gained conspicuous popularity in all the ancient civilization of the world. It is evidently clear through the exposition of different civilization that have been flourished in large numbers and over a wide range of the countries between Persia and the Aegean, notably in Elam, Mesopotamia, Trascapasia, Asia Minor, Syria, Cyprus, Palestine, Crete, the Cyclades, the Balkans and Egypt (Mar- shall: 1931 : 50). In fact, in India, it still constitutes a basic element of socio-religious sphere of life of the people as a whole.

In the pre-literate society, life at every point and every state was imagined to be ruled by some rhythmic process, the alteration of life and death. In the prehistoric period, religion centred and developed round the three most critical and perplexing situations with which 'Early Man' was confronted with his everyday experience-Birth, Death and Means of subsistence in a precarious environment (James: 1957: 229).

Primitive religion was highly influenced by the multiple supernatural forces-the powers and spirits that shape one's destiny; some of these were ascertained by them as benevolent and others appeared before them as malevolent (Majumdar: 1958: 406). Hence the main object of the religious concept at the very initial stage was to propitiate innumerable spirits, which were believed by the members of the pre-literate society to be closely connected with their very existence in this earthly world, and even after death. It is the case throughout the old world.

Another essential aspect of the religion of the preliterate society was that each hamlet, settlement or village thought to have been under the protection of some particular spirit who was treated as its "guardian deity" or the "tutelary deity". The concept of the guardian deity, may, in the later period, be turned into the nucleus of the formation of several folk deities.

After the introduction and gradual growth of the agriculture-based civilization, new religious concepts and movements, ideas and ideals, rites and rituals came into being and these naturally arose from people's vis-a-vis their surroundings. At that time, the life-producing mother was thought to be the central figure in the human and animal kingdom and gradually extended to the agricultural fields and meadows. Then the 'Mother-earth' was imagined to be the womb in which seeds were sown and germinated. Subsequently, the Mother Goddess was assigned a spouse to play the rule as begetter and she was clearly the chief anthromorphic object of worship, depicted either alone or in association with her characteristic emblems and accompaniments-serpents, lions, doves, shells, the double axe, some kinds of trees, and mountains, in which divinity was implicit (Zambotti: 1962: 58).

Further, the 'Mother-Earth' was essentially connected with good luck and prosperity (Dikshit: 1943 : 8). The presi.ding deities of agriculture were mainly treated as female beings, because the idea of fertility and reproduction was primarily connected with the women. As the grain-gathering was women's business, it is presumed that, agriculture was invented by the women folk (Bernal : 1969 : 93). Primitive agriculture, that is. gardening-understood as a magico-religious activity, was therefore a feminine reserve, probably from the Paleolithic onward~ (Zambotti: 1962: 58). Accordingly, the women's side of the totemic rituals for increase and reproduction of plants was emphasized and further developed (Bernal: 1969: 98). Obviously, various activities relating to that particular state of economy was controlled by the women folk. Probably all these facts led the members of the pre-literate society to form an idea of female deities or goddesses rather than male-gods (Whitehead: 1921: 150). Moreover, the fertility cult seems to have persisted right down to the classical times. As civilization developed around the shores of the Mediterranean, a paramount female goddess, the 'Great Mother', took a prominent place in almost every pantheon (Leonard: 1974: 112).

The religion of the aboriginal Indian folk did not advance beyond a crude 'animism' and. belief in the presence of the 'guardian deities' was its chief characteristic. We have got almost full-fledged knowledge about the development of the earliest society in India which is highly characterized by the various literary compositions of the Aryans, specially the Rig Vedic literatures. On the other hand, we are not so much well informed about the various internal forces which came to be associated with the different spheres of the society that flourished on the bank of the river Indus and its tributaries. It is difficult to form a clear idea about the true contents of the religion from the materials unearthed at Indus Valley sites. Further, it must be remembered that it is a great problem to draw a line between the secular and religious concepts of such an early culture (Vats: 1958: 121). Some scholars believe that the destruction of the Harappan civilization was brought about by the Aryan invaders, whose date of entry into India has been roughly confirmed between 1500 B.C. and 1000 B.C. (Cf. Robert Heine-Geldren: 1956: 136-40; Pusalker: 1951 : 197; Wheeler: 1960: 86), though the fact is still doubtful to others, as there is no concrete evidence of destruction in such ways, However, the Aryans in the subsequent period, gradually spread throughout India and introduced new special order and religious institutions, namely, "Vedism", 'Vedism' was the earliest known form of religion followed by the. Indian branch of Aryan family, and in the later period, 'Brahminism', a changed form of religion grew out of 'Vedism'. Brahminism has been modified by the creeds and superstitions of 'Buddhists' and the so-called non-Aryan people including Dravidians, Kolarians and perhaps pre-Kolarians (Monier Williams: 1883 : 2) ,

In the Vedic period, as we find in the sacred scriptures like Rig Veda the society has sharply divided into two spheres, namely, the 'Aryans' and the 'Non-Aryans'. These two divisions were highly influenced by manifold interactions. The members of the non-Aryan communities had generally been treated as the 'Dasa-Dasyu',-the dark-skinned outlandish barbarians, by the Aryan community.

The Aryan society was mainly composed of the Priests, the Warrior, the Nobility and the Common folk. It is believed that the 'caste system' was introduced by the Aryans and it became much popular in the subsequent period amongst the Indians. Scholars refer to a myth depicted in the holy writ Rig Veda (X.90) which indicates the basis of emergence of the caste" system in the then Aryan society. In the said myth, the creation of the four classes or castes, that is, Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaisya and Sudra is narrated in a brief manner. It is evident that the term 'Brahminism' refers to the fact that a definite type of Priest-caste, that is, the Brahmin took. the leading part in the sphere of religion developed in the- Aryan-speaking region (Weber: 1958: 4). Obviously, the post-Vedic period saw the growth and consolidation of the power of the Brahmins. Brahmin writers continually discussed' and defined the duties and rights of each caste and its place in the hierarchy (Srinivas: 1965: 503). It is beyond doubt that the vast community composed of non-Aryan folk was placed in the 'Sudra' category, by the Aryans. Sudras originally included the members of the pre-Aryan and non-Aryan societies, who were referred to as 'Dasas', 'Dasyus', 'Kiratas' and 'Nisadas', etc., in the subsequent period (Sengupta: 1951 : 24; Pusalker : 1951: 261).

Further, it is doubtless that the Rig Veda is the product of the highly priestly class people, who have had almost a monopoly of officials, teachers and scholars of Vedic culture in India. In the holy writ like the Rig Veda, we find not only the classification of the inhabitants but also the names of the different deities of the 'Aryan'3 pantheon, who, in course of time, were directly absorbed in the world of the vast ‘Hindu’ theogony. The characters and activities of these deities are- narrated with some glorious background in the sacred texts composed in the different periods, from Vedic to recent times.

In India, from hoary past the religion plays a dominant and vital role in the daily life of the common folk. The nature of religion in the historic period can be grouped primarily according to the philosophical views and explanations including all other aspects and characteristics, namely, Vedism, Brahminism, Buddhism, Jainism and so forth. The religions of India, in their association with the major part of her people, have conveniently accepted the name 'Hindu'. The very nature of the religion, as we find in the sacred scriptures of the Aryan' or the Hindus, namely, the Vedas, the Samhitas, the Aryanakas, the Brahmanas, etc., were, however, not the only religion practised by the Indian folk. That is, apart from the vast world of Vedic-Aryan theogony or the Hindu-Brahminical pantheon, there lies an extensive field consisting of the deities of the pre-Aryan and non-Aryan communities whose names and genealogy, characters and activities were not referred to in the Vedic literatures or such other holy writs composed in the remotest past. This fact may be explained in a way that the deities of the non-Aryan world did not hold any good position in the Aryan society during the Vedic period. But this picture has been. changed in the subsequent periods. As the time marches on, the Aryan influence began to penetrate in the different parts of the Indian sub-continent and simultaneously the Brahmins, that is, the priestly ministrants including such other high-ranking people had to accept the religious beliefs, crudest rites and cultures practised by the pre-Aryan, non- Aryan Common folk including the propitiation of primitive deities in order to maintain their own power and influence over the innumerable common people of India, irrespective of rank and status. But in fact, we hardly possess any literary source of the most ancient time, which would help us to have any clear concept about the religious dogmas and practices of the large section of the pre-Aryan and non-Aryan people of India. This trend of religion may be termed as the "popular folk religion" and it is obviously the outcome of the interaction of various belief and ideas of indigenous origin. It embraced diverse thoughts and ideas, which, in different times, gave birth to many indigenous ideas. In most of the cases this trend is not guided actually by the monastic rules. Though not bounded by the monastic rules and regulations, yet the popular folk religion has been and still remains as one of the main and vital resources of many prevalent religious beliefs, customs and cults, rites and rituals, taboos and manners in India. In fact, the religion-cultural pattern of India is mostly based on the unfolded and checkered history of the common folk, their deities, beliefs and religious faith, rites and rituals, ceremonies and festivals. Still there is an enormous scope to study the various folk deities who have the power to cater to influence on the livelihood and natural discourse of the common folk.

There is every probability that in the society of good old days, a 'faith' originated or germinated in the minds of the members of the society, merely based on the necessity and experiences of the daily life, which, in the long run, did a great deal in creating the part and parcel of the religious beliefs and practices, ceremonies, rites, rituals and cultus (Fuchs : 1963: 218). In this way innumerable female deities managed to get their conspicuous' position in the sphere of Hindu-Brahminical religion subsequently identified as the 'Sakti" or the 'Prakriti' (feminine principle) of the male-god. The female principle, that is, Sakti alias Prakriti, in the Samkhya» philosophy es well as in the Tantric religion, plays an important role with the 'Purusa' (i.e., male counterpart). During the later Vedic period and Puranic Age there was an attempt of assimilating some pre-Aryan mother goddess forms with 'Prakriti' or the female counterpart of the 'Father- God'. who, in course of time, emerges as the Supreme Being (Sinha : 1967 : 50), though there was almost no example of the ancient Aryans, whether in India or elsewhere having elevated a female deity to the supreme position occupied by the Mother Goddess (Farnell: 1911 : 95-96).

Contents

| Preface | Vii | |

| Foreword | Xi | |

| Chapter 1 | ||

| Introduction | Jan-28 | |

| Chapter II: | Cult of The Mother Goddess And Candi | |

| Genesis and Concept of the Mother Goddess | 29-36 | |

| Earth as the Replica of the Mother Goddess | 36-42 | |

| Conceptualization of the Mother Goddesses through Trees and Plants | 42-58 | |

| Chapter III: | Mother Goddess Candi As Depicted Through The Ages | |

| Mother Goddess: In the Pre-Vedic Civilization | 59-65 | |

| Mother Goddess: In the Vedic Scriptures | 65-73 | |

| Mother Goddess: In the Post-Vedic Scripture | 73-86 | |

| Chapter IV: | Candi: The Mother Goddess In West Bengal | |

| Candi : The Mother Goddess in Preliterate Society | 87-92 | |

| Candi : Popular Folk Deity in Bengali Verses | 92-106 | |

| Candi : Household Deity in Deltaic Bengal | 107-114 | |

| Candi: Goddess of Disease and Cure | 114-116 | |

| Candi: Traders' Tutelary Deity | 116-120 | |

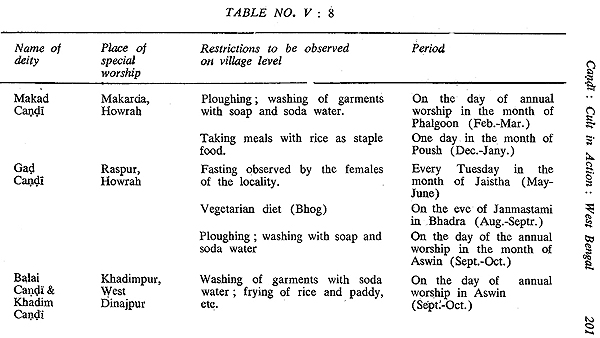

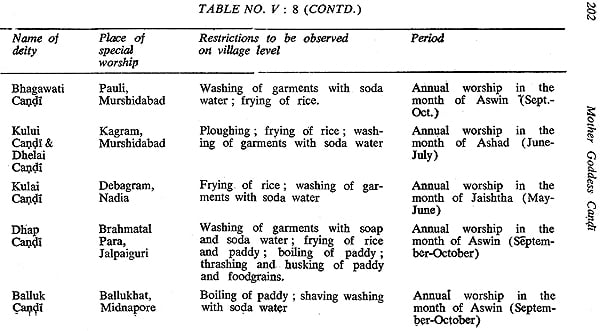

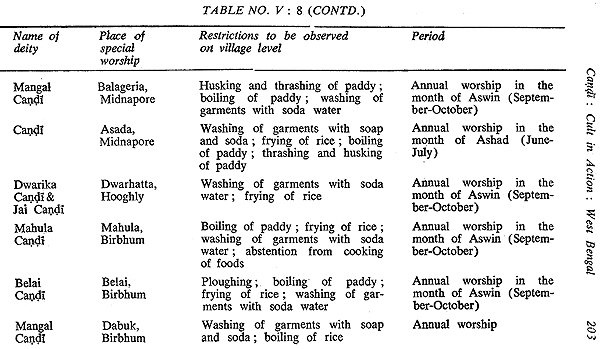

| Chapter V: | Candi Cult In Action: West Bengal | |

| Impact on the Socio-Religious Life | 121-200 | |

| Common Religious Bond | 200-206 | |

| Role of Candi in the naming pattern of village | 206-215 | |

| Chapter VI: | ||

| Conclusion | 216-239 | |

| Appendices | ||

| Notes | 240-247 | |

| Glossary of Local Terms | 248-252 | |

| References and Bibliographies | 253-270 | |

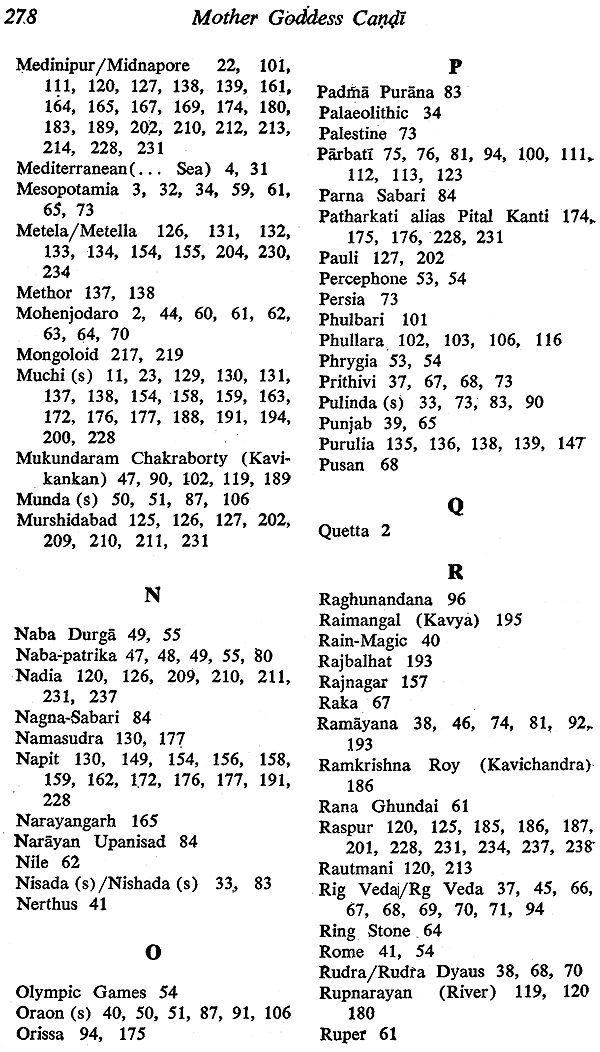

| Index | 273-279 | |

| Errata | 280 | |

| Maps | ||

| Plates |