The Power of The Female: Devangana Sculptures on Indian Temple Architecture

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF484 |

| Author: | Gauri Parimoo Krishnan |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| ISBN: | 9788124606872 |

| Pages: | 474 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.0 inch x 9.0 inch |

| Weight | 2.47 kg |

Book Description

Although devangana (celestial female) is a ubiquitous motif in the visual arts and architecture of India and those artistic traditions inspired by Indian aesthetics, the literature on the subject is less than abundant. Dr. Gauri Krishna, a well –known art historian now fills that lacuna with a volume that analyses the me in depth and breadth using multiple disciplinary perspectives.

The outstanding feature of this scholarly work by Bharatanatyam exponent, art historian, curator and scholar-Gauri Parimoo Krishnan is, it unravels multiple levels that contribute meaning to the celestial women, who are certainly not mere aesthetic appendages decorating temple walls. Besides reviewing the work of senior art historians, she interprets the motif of devanganas from the perspective of feminist interprets the motif of devanganas from the perspective of feminist intervention, not attempted so far, allowing different insights into the history of temple architecture and sculpture. She has brought to her study of these sculptures-practical knowledge of a dancer and the discipline of an art historian. The application of aesthetic principle of dhvanin is another major contribution. The representation of feminine power has been studied, analyzed and interpreted in a path-breaking novel way.

For the first time a study has been made in the context of semiotic analysis and the dhvani theory of Indian aesthetics to unravel the meaning of the sculptural motif of celestial woman, variously called devangana, surasundari and apsaras. The study of the typology, programming and the pattern of placement of various devangana figures on western and central Indian temples, dated between eighth to twelfth centuries, is Krishna’s contribution to the subject. The author has tried to unravel multiple levels of meaning, studying these celestial women individually and totally. This iconological study provides cultural connotations of the motif showing its continuity in the visual imagery and form of the yaksi sculptures of the earlier Buddhist and Jaina monuments.

About the Book

This book is an offering to New Art History taking the study of Indian classical sculptural art and traditional India iconography to newer heights of interpretation. Sculptures of female figures in classical India architectural traditions have enjoyed a special placement and significance. Numerous engaging images of devangana- the sura sundari, apsaras and alasakanya figures –decorate wills, ceilings and doorways of Hindu temples in India. Viewing the devangana sculptures as continuation f he uaksi sculptures of Buddhist and Jaina monuments and the concept of primordial mother goddesses of het Vedic times, this challenging work on the devangana sculptures studies the morphology, iconology and semiotic meanings of the devangana figures and their placement in monuments of Gujarat, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh between the eighth and twelfth centuries ce.

In a path-breaking effort, the work focuses not on the much-discussed erotic and sexual connotations but explores their dynamic meanings in the religious and cultural consciousness which help to symbolize “the power of the female’ in representational artistic traditions of India. For this, copious architectural and religious texts are examined. With more than 250 illustrations of temple sites and detailed sculptures, this book enquires into the imagery of these figures. A significant aspect of the research is its critiquing of the existing literature on the subject to come up with novel viewpoints and se of tool like dhvani theory, psychoanalysis and feminism t interpret the devangana sculptures.

The book will benefit young researchers, cultural enthusiasts and erudite scholars of India art and architecture focused on religious and cultural significance of India’s sculptural heritage.

Dr Gauri Krishna specializes n South Asian Art History and Performing Arts. She obtained her PhD in Art History from the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, India where she taught Art History and Aesthetics before moving to Singapore. She developed the Indian collection as the founding Curator for South Asia at the Asian Civilizations Museum and was the Deputy Director for Research and Publication at the museum. She is currently engaged in the development of the Indian Heritage Centre project of the national Heritage Board, Singapore as its centre Director working closely with the India community.

She received Singapore Government’s Commendation Medal Pingat Kepujian in honour of her contribution to the development of the Asian civilizations Museum’s collections, galleries, exhibitions ad publications. She is the recipient of research grants of het Victoria 7 Albert Museum, London; the Gurgaon; Monash University, Melbourne and the National Heritage Board.

Gauri has curated many seminal block-buster exhibitions, lectured on Ndina art and the Diaspora; published extensively in reputed journals; her major publications are : Images of the Compassion: The Art of Naina Dalal (ed. 2000); Ratan Parimoo: Ceaseless Creativity –Paintings, Prints, Drawings (ed. 2000); The Divine Within : Art and Living Culture of India & South Asia (2006); Visual and Performing Arts of Asia (ed. 2010) Her for coming edited volumes on Buddhist Art of Asia and Indian Trade Textiles will be seminal contributions to new research on Indian and Asian art.

Gauri Parimoo Krishnan represents a younger generation of art historian who have imbibed the knowledge and approach to Indian art of their peers but who have also critiqued on investigating a “ motif” in Indian art which pervades all schools and styles of Indian art, from about the second century BCE the fourteenth or fifteenth century CE. The “woman and tree” motif has been the subject of investigation by historians of Indian art ranging from Ferguson (Tree and Nature Worship) to Vincent Smith and, more importantly, Vasudeva Saran Agarawala, A.K. Coomaraswamy, Stella kramrisch as also the present writer (Kapil Vatsyayan).

The salabhanjika, known by her various names- surasundari, apsaras, madanika , alasa kany and many others- are integral to the architectural schema. They can be as bracket figures as in Sanc, they can be railing figures as in Mathura, they can hang loosely form pediments, and they can even surround the outer and inner walls of temples, Hindu and Jaina alikle, A.K. Cooomaraswamy delves into the subject, focusing his attention on water cosmology. Vasudeva Saran Agrawala classifies them into sub-categories, especially in the context of Kusna (Mathua). Stella kramrisch elucidates upon them in the context of the Hindu temples, particularly Khajuraho.

Devangan Desai investigates them within the framework of her principal argument of religious imagery. Kapila Vatsyayan examines the motif from the point of view of movement. And now Gauri Parimoo Krishnan looks at this subject anew, while maintaining continuity but not repetition. She has assiduously perused the critical analyses of her predecessors and has assiduously perused the critical analyses of her predecessors and has gone further by concentration attention on the morphology of architecture and the place and devangana sculptures within the architectural schema.

Gauri Parimoo Krishnan meticulously looks at the critical literature of the twentieth-century scholarship an re-examines some of the earlier classifications. She extends her investigation very pointedly to medieval western Indian sculptures, modeling, form and style. Here she takes into account the valuable and path-breaking work of U.P. Shah as also M.A. Dhaky. However, here there are both fresh insights, and new material.

Gauri Paimoo Krishnana commences her study with an introduction clearly outlining the scope of her study, as also the methodologies and strategies she proposed to adopt. The introduction takes in to account studies on the subject as mentioned above, but it states clearly that at the level of methodology she proposes to apply both Erwin Panofsky’s formulation in studies in iconology ( 1950) as also Anadavardhana’s theory of dhvanin (i.e theory of meaning ). She elaborates on the latter. This juxtaposition is a welcome fresh approach which will stimulate critical reflection.

Gauri Paimoo Krishnan carries her narration through seven chapters from these multiple perspectives and methodologies of interpretation. All this is brought together in the final eight chapter. Here she presents her own formulation on the iconological and semiotic interpretation of the devangana motif. She adopts the “semiotic interpretation of the devangana motif. She adopts the “semiotic method” and subscribes to the Morris’ view of semiotics. She returns to juxtaposing this with theories of Anadavardhaa. She elucidates on symbiosis, the semantically paradigramatic dimensions and returns to state that it is truly significant that the principle of dhvani in Indian literary criticism is so closely analogous to he semiotic analysis. She carries forward her argument convincingly to enunciate a “diagrammatic analysis of the devangana motif”. This diagrammatical analysis is a new and welcome theoretical formulation. I have n o doubt that the arguments given and the conclusion drawn will engage scholars in the future.

It has been a great pleasure and education for me to read this seminal impressing comprehensive study.

The discipline of art history is multi-dimensional, always inviting the scholar t undertake new journeys on age-old material. Painstaking, sincere endeavors such as this are significant milestones.

Arigourous training in the twin disciplines of Bharatanatyam and History of Art has moulded my vision to explore areas of learning still neglected and lacking in scholarly rigour. Having settled upon field-based research, I found Gujarat, the state where I was born and grew up, the most accessible. I visited a number of architectural sites in Gujarat and Rajasthan to make first –hand observations since the 1980s. Eventually, I widened the scope of my research to include adjoining areas of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, which have close cultural affinity with Gujarat.

For two decades I have been concerned with tripartite comparative analysis of dance text, its representation by an artist in painting or sculpture and its recreation in dance by a performer. At one stage, I had confined myself to Gujarat and Orissa, while the textual references focused on nrttahastas, sthanakas and caris from various texts.

The present concern is an outcome of the above focus on sculptures of the surasundari, apsaras and alasakanya that gradually became the most engaging, intriguing and challenging subject t of my study. The more I saw them, the more elusive they became. This book is a holistic inquiry into their imagery, their evolution on various India monuments and the cultural connotations associated with their placement and meaning. In attempting this, I am focusing mainly on the “content” analysis as Panofsky (in Western art history) has demonstrated, without overlooking formal and stylistic analysis of the sculptural form. Most monuments’ discussed in this book are from the eight to twelfth century CE, since the major efflorescence of devangana imagery appeared on the temple architecture during these four centuries.

I have used the term devangana to refer to the so-called surasundari, apsaras and alas kanya figures, because this term was originally used in Vrksarnava, an architectural text from Gujarat and it is the only term in my view which is devoid of any erotic or sexual prejudice. It denotes divine beauty or a beautiful divine female. Terms like surasundari, apsaras, madanika, alasa kanya refer to their amorphous and amorous characters; they are created and dissolved at will to allure the mankind with the power of their beauty.

Some are often spoken of as the dancers of Indra’s court, while some bear the connotation of divine courtesans and prostitutes. The nati, nartaki or nayika imply they are dancers or characters of a play. In the light of my interpretation, the erotic connotation or the aspect of beauty ad eroticist has been overridden by an urge to explore more dynamic meanings in the light of human cultural consciousness, “the power of the female” , which is not necessarily religious, erotic or anything trivial. Instead, I have tried t focus on their image typology, its programming and placement on the temple wall. I urge the reader to visualize what is the role of the devangana sculptures in the cultic context, what role would a chief priest or chief sthapati play in the planning of the iconographic arrangement on a temple wall. Were there specific rules and injections laid down by the sthapati or, were there specific rules and injunctions laid down by the sthpapati or, were the sculptors free to use their creative and innovative ideas in configuring the images of the devanganas?- these are some of the questions I have raised and tried to answer. Did sculptors specialize in carving devanganga figures or would the same sculptor carve a devangana, a Visnu and a Siva statue? Since many of the Silpa texts are dated later than the temples, one would imagine that they record a prevailing practice and continuing oral tradition and not theoretical prescriptive rules.

Below is an attempt to enumerate a critique of the writings of significant scholars on the salabhanjika, surasundari, and apsaras which has received some attention but not warranted a full-length book, which is why I feel this book shall fill some gaps. Using the field research material and various methodologies of the Western and Indian scholars such as Vogel , coomoaraswamy, Stella Kramrisch, V.S. Agrawala , Motichandra, C. Sivaramamurti , M.A. Dhaky,Kapila Vatsyayan, Pramod Chandra, Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty, RatanParimoo, Darielle Mason, Vishakha Desai, Vidya Dehejia, and others, I expand upon the existing interpretations and explore new avenues. The theories of “Iconology” and “semiotics” of Erwin Panofsky and Roland Barthes respectively, along with psychoanalytic approach of Freud and Jung have also lent sufficient insight into the “contextual” interpretation of a work of art. Writings of Ernst Cassirer regarding symbols formation and the philosophy of Human Culture have been a path breaker. I have tried to absorb some relevant concepts from their theoretical writings to analyses the devangana imageries in the context of Hindu –Buddhist and Jaina architecture and the evolution of their imagery from the earlier forms of primordial mother goddess figurines, salabhanjika-vrksika-yaksi, river goddess-nadi-devatas to devanganas. The theory of evolution of imagery can also be observed in the structure manner in which the American Institute of Indian studies has produced its Encyclopedia of Tempe Architecture. This methodology of Dhaky and Meiseer has provided a framework for observing comparative trends within one motif or iconographic construct or regional sculptural or architectural styles. Drawing attention to the placement of the devangana imagery on temple walls and their relation with other sculptures on the same wall and the entire edifice in the manner of Stella Kramrisch has taken my study to another plane-it has become a structured approach to deconstructing their meaning and reconstructing their function in a dynamic process. Following the trail of Kramrisch and Dhaky, I launch on this exploratory and interpretative journey armed with multiple tools from Indian and western traditions.

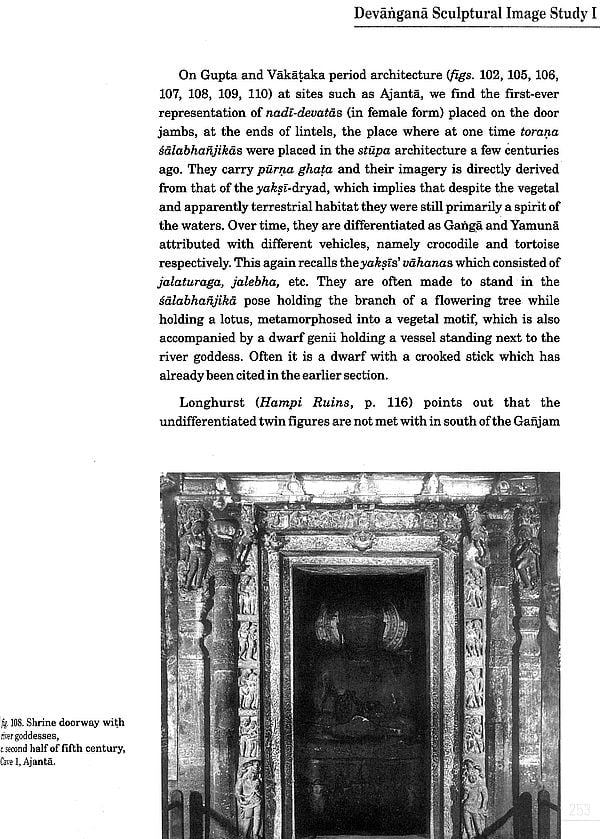

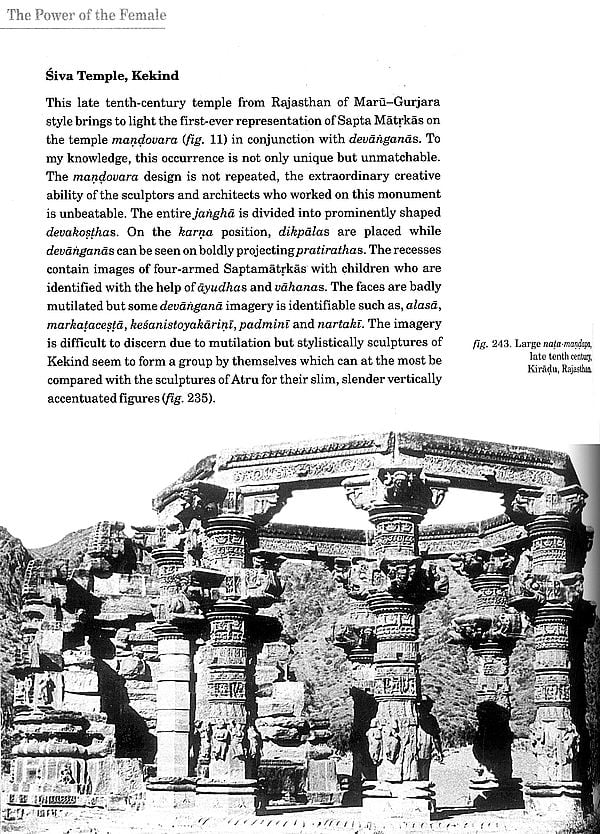

Before critiquing the existing literature and unfolding my methodological concerns, I wish to state that the present thesis attempts to perceive the apsaras/devangana sculptures as a continuation of the yaksi sculptures found on Buddhist and Jaina monument and further afar into the imageries in the Vedic texts of primordial mother goddesses such as Raka, Sininvali an Aditi. In sculptural representation of these celestial figures, one can notice that not only yaksis, and salabhanjikas, but even nadi-devatas (river goddesses ) and nayikas (heroines) played a important role in the development of their iconography. This can be observed at many sites such as Ajanta and Ellora in Maharashtra, Jagat and Mt. Abu in rajasthan, Badoli and Khajuiaho in Madhya Pradesh and Roda, Rani Vav and Modhera in Gujarat. There are some obvious iconographical representations which are found with staggering regularity on most of the Nagara style temples such as darpana (holding mirror ), alasa (longingly waiting), vasanabhramsa (removing the lower garment), kanduka-krida (playing with a ball), kesanistoyakarini (bathing beauty0, putravallabha (holding a child), sva-stana-sparsa (touching her breast), markatacesta a(veing disturbed by a monkey), vira (holding a weapon)m natipvartaki (dancing) and prasadhika (doing make-up-). Some architectural texts from Gujarat virksarnava and kisrarnava (fourteenth-fifteenth centuries ( mention a list of 32 devanganas suggesting that the details relating to this group of images was circulated within sthapati families and was known orally in many regions. I will elucidate on these devanagabasm their typology and how in a synchronic and diachronic way they coalesce into a vision of ever-changing cyclic order towards asceticism, eroticism, creativity and annihilation. It is the “continuity” and “constancy” in imagery that constitutes the raison d’etre of my inquiry.

Critique of Earlier Writings

The concept of the famine energy personified in Indian culture, thought, art and literature, is irrevocably immersed in the Indian psyche. IN ht course of the present research I found that the representation of the female, other the goddesses per se, contained connotations of verity, fertility, eroticism and asceticism that broadly oscillate between, “material” versus “spiritual” polarities. IN the process of collecting observations and interpretations of earlier scholars, I noticed that the subject of saslsabhanjika or apsaras has engaged the interest of many earlier scholars. But surprisingly their probing and interpretations have remained unidirectional.

Vogle proposed the concept of salabhanjika in literature and art to understand the evolution essentially of the “woman and tree” motif. From a seasonal festival to an allegory of fertility-the standardization of its posture, is shared by Mayadevi in the birth-giving pose on Buddhist monuments. He also noted the continuation of this motif from a community festival to an architectural motif wherein any type of imagery is classified under the term salabhanjika. Thus the term is conceived very broadly and the imagery is left fluid. Vogel enumerate literary data from Sanskrit texts, prose and verse literature like Natyasastra, Mahavamsa, Buddhiacarita and Simhasanabattisi. Vogel’s interpretation has been repeated by Coomaraswamy, B.M. and R. N. Misra in their researches on yaksa cult and Bharhut sculptures. Since the scope of their research was specific, they did not delve deeper into t he wider connotation of the salabhanjika motif, its related imagery and its continuation in later architecture.

But coomaraswamy rightly observed that the yaksis (carve on Bharhut, Saci , Mathura ) give rise to three ichnographically identical motifs, albeit differently interpreted : the Buddha’s nativity , “the asoka dohada motif in classical literature”, and the “river goddesses of medieval shrines”. He also distinguished between the gandharvis, apsaras, et. And pointed out that it was incorrect to call them merely dancing girls. Although indirectly, Cooomaraswamy was probably the first ever t hit at the continuation of yaksi salabhanjika imagery in later sculptures of surasundari, on temples architecture. I believe that the continuation or recalling of similar motifs on different monuments after a long lapse of time does not mean these had been erased from the memory of artists’ visual vocabulary of motifs an image. They may have survived in other forms to be recalled back at an opportune time when a appropriate function on an appropriate monument may have emerged.

The contribution of V.S. Agrawala to the study of yaksi-salabhanjika –vrksika motif in the light of the Sanskrit literary data is extremely insightful. In his work, begum in the 1940s on Mathura sculptures, he identified the imagery of a number of female sculptures such as sukasarika, kesanistoyakarini, veniprasadhana, asoka dohada, putravallabha, kanduka-krida and padmini. He also bought to light the numerous references from Sanskrit, Pali and Prakrt sources, Parallel motifs or imageries of nayikas as described by the poets and dramatists like kalidasa, Bana,Asvaghosa, Rajeskhara, Bhoja and others. A whole range of kridas such as udyana-kridas and jala-kridasa re mentioned by him with literary references to show the cultural context from which the imagery of a number of yaksis on Mathaura pillars was derived, He has given only stray references to alas kanya and others on later temple architecture. Agrawala does not observe any parallels or evolution in any single imagery type, e.g. kesanistoyakarini, through the centuries from stupa architecture to temple architecture. The book Indian Art (1965) treats the topic of Kusana salabhanjika at great length. The development of the motif in the post-Gupta and the medieval period has been left out.

C. Sivaramamurti, in his enormous study on Amarvati sculptures (1942), brought to light a number of references to yaksi in architectural contexts from epic and classical Sanskrit literature like the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Mahabhasya and Raghuvamsa. He also noticed the overlapping meanings shared by the imagery of yaksi, Sri and nadi-devatas, i.e. bestowing prosperity and abundance. In his subsequent book, Sanskrit Literature and Art: Mirror of Indian Culture (1955), he devoted one section to salabhanjika and stambha puttakika, which are very brief and do not provide much insight.

References to apsaras in the writings of indologists and iconographers have been found much before art historians began to study them in earnest. Vedic Mythology of A.A. Macdonell(1898) and A.B. Keith (1925) contain enormous information from the Vedic and Puranic sources on apsaras. An extensive study of iconography with supportive discussion on parallel manifestations through the ages done by T.A. Gopinath Rao (1914-16) and J.N. Banerjea (1956), have brought to light one significant observation on associating Bharhut apsaras Misakosi, Alambusa and others with the sculptures of later day Ganga and Yamuna on Hindu temple architecture. Banerjea justifiable observed that the imagery of Ganga-Yamuna could be traced to the Bharhut prototypes (apsaras) even though they are not depicted in dancing postures. Thus the “continuity” of the visual imagery an form from yaksi-apsaras to nadi –devatas was hinted at by Banerjea in 1941 in his Development of Hindu Iconography, but a systematic study was still wanting. The identification of dance postures had to wait for Kapila Vatsyana’s research on Classical Dance in Literature and the Arts (1968), which was conducted during the 1950s. Now we know that every sculpture, standing or seated, of human figures, could be identified as a sthanaka or a cari conforming to the study of sculpture an literature and the inseparable, almost “symbiotic” relationship, shared by the visual, literary and performing arts in India. A number of sculptures of hither to classified apsaras, yoksis, devanganas and surasundaris, have been discussed by her from the context of their dance postures.

The apsaras, salbhanjik concepts in literature and the arts have been dealt with independently by two scholars, namely Projesh Banerjee (1982) and U.N. Roy (1979), which harks back to the method of the recent researches of specialized nature and contain larger compilation of references from the Vedic, Puraninc and classical Sanskrit sources. Projesh Banerjee also brings in devadasis as the “daughters of e celsestial apssara” and extends the interpretation to temple ritual, but fails to project any formidable conclusions. U. N. Roy in his study on salabhanjika refers mainly to the Kusana period, and rounds off the Gupta period summarily. Although he mentions the continuation of this motif in nadi-devatas, he has made no efforts at elaborating and establishing the links. Motichandra (1973) , in his book The World of Courtesans refers to apsaras as courtesans and reduces the the level of divine prostitutes power. The book incorporates photographs of apsaras interpreted as courtesans.

At this juncture, I pause with some questions-what are the apsaras or devanganas doing on a temple? What role do they play in the architectural and sculptural programming (plan and layout) of the temple? What is the meaning of their action? Does their iconography have any meaning? Why are certain types of devangana repeated on many monuments across different regions over several centuries?

By far the most brilliant interpretation of surasundari and apsaras sculptures in conjunction with temple architecture in the light of the above question and in the larger context of the temple’s iconographical programming, has been attempted by ?Stella Kramrisch way back in the 1940s, followed by Alice Boner in the 1950s.

| Foreword by Kapila Vatsyayan | vii | |

| Acknowledgement | xi | |

| List of Photographs | xiii | |

| 1 | Introduction | 1 |

| 2 | A Medical Historical Backdrop Apsaras Imagery froom Sanskrit and Prakrt-Sources | 31 |

| 3 | Apsaras Imagery from Sanskrit and Prakrt Sources | 53 |

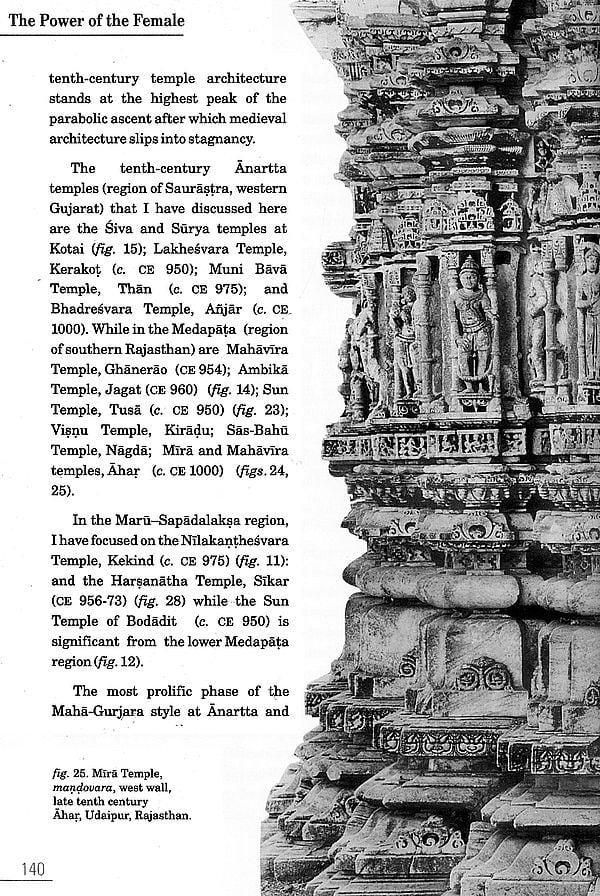

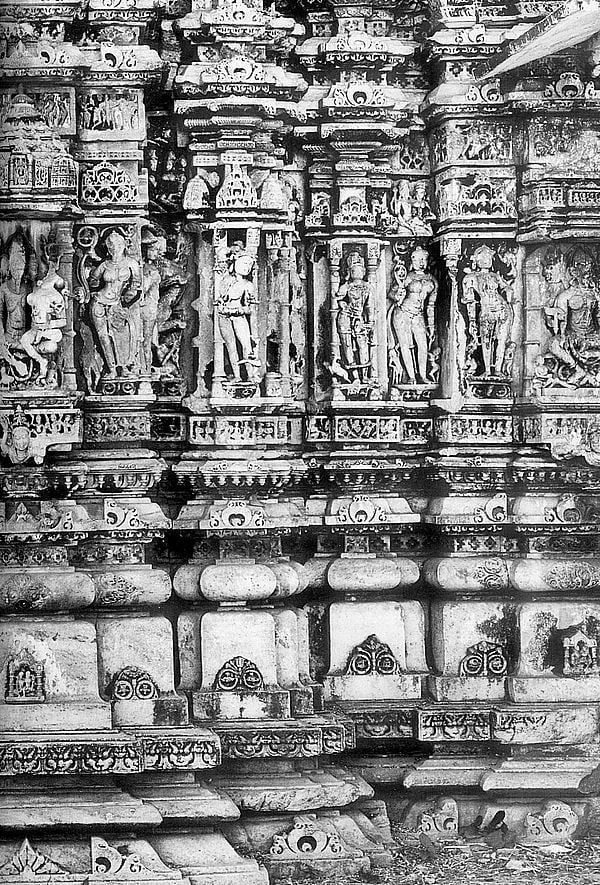

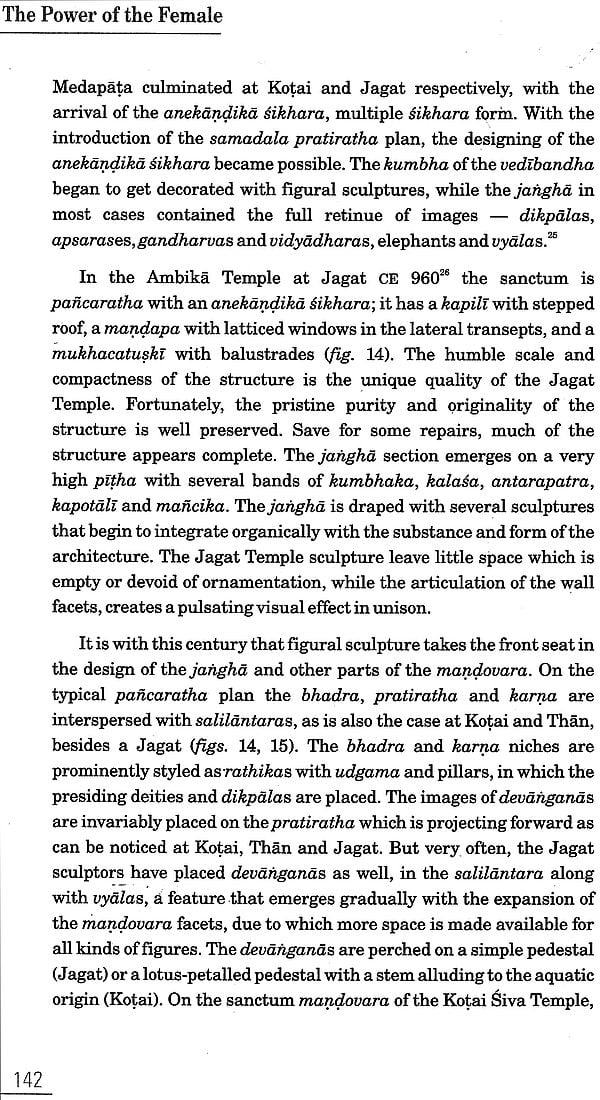

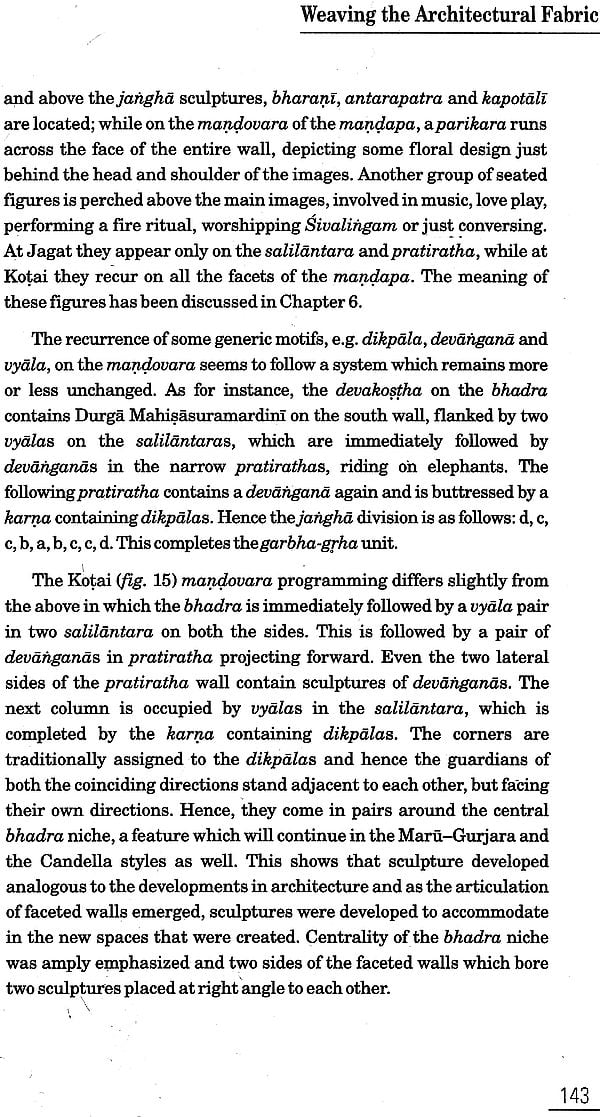

| 4 | Weaving the Architectural Fabric: Morphology of Architectural style and Placement of Devangna Sculptures | 105 |

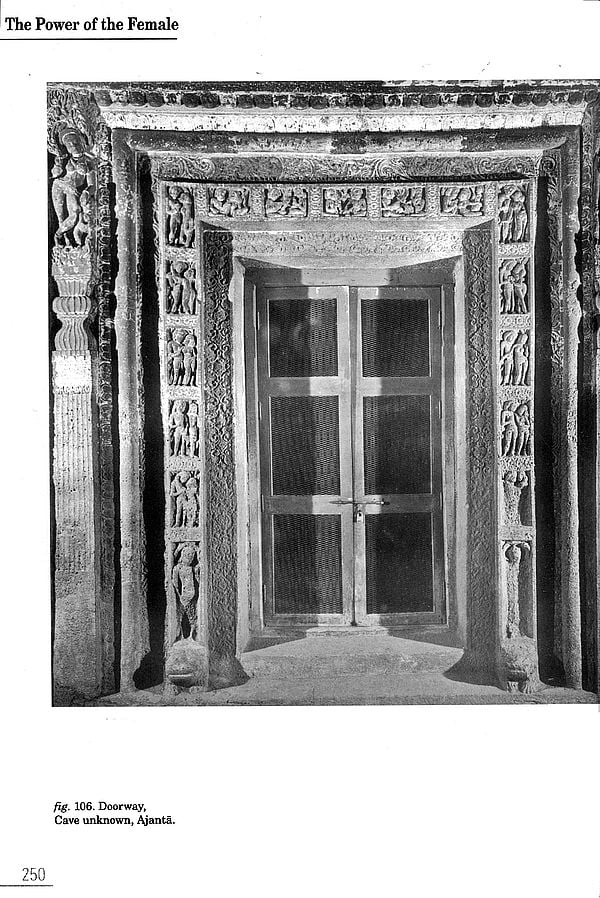

| 5 | Devangana Sculptural Image Study I: Emergence and Evolution of Individual Motif Types | 185 |

| 6 | Devangana Sculptural Inage Study II: Post-Gupta and Medieval Devanganas | 271 |

| 7 | Medieval Western Indian Sculpture: Modeling the Medieval Form and style | 357 |

| 8 | Iconological ans Semiotic Interpretation of the Devangana Motif | 377 |

| Appendix | 421 | |

| Glossary | 429 | |

| Bibliography | 433 | |

| Index | 445 |