At the Feet of Living Things (Twenty-Five Years of Wildlife Research and Conservation in India)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UBA723 |

| Author: | Aparajita Datta, Rohan Arthur & T.R. Shankar Raman |

| Publisher: | Harper Collins Publishers |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9789394407855 |

| Pages: | 407 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 330 gm |

Book Description

IT IS A PRIVILEGE TO write a foreword for a collection of essays Lby members of the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF). Twenty-five years is but a blip in historical or, for that matter, ecological time. But it is a landmark in human lifetime. Equally so for an organization with a mission and a cause.

To work collectively for conservation and more generally for and with nature was cause for a small celebration. It was especially welcome in India a quarter of a century ago. Far-reaching economic reforms and socio-ecological and cultural shifts were remaking the landscape, generating new pressures on the environment even as growth picked up steam. To attempt to put science, mainly biology, and link it to conservation as a practice was a big leap if not a great one. Since then, the foundation has grown in numbers of scientists, staff and personnel. Individual members as well as the organization have won recognition in India and abroad.

For a quarter of a century, the collective has held together mainly due to its shared ethos, culture and structure that combine team effort with room for diversity at the level of programmes. Many key wildlife, ecology and conservation initiatives have been centered on charismatic individuals. After the Second World War, the UK (United Kingdom) saw Peter Scott set up the Severn Wildfowl Trust; Philip Wayre's Wildlife Trust in Norfolk focused on England's native fauna; and the author and naturalist Gerald Durrell had his special zoo for endangered species in Jersey in the Channel Islands. Each of these survived the demise of their founder but the vision and mission were clearly spelt out by the man who started it all. A second model has been of a group of influential individuals who banded together for a cause, as with the New York Zoological Society and the National Audubon Society in the US. India, in 1969, got its own chapter of what was then the World Wildlife Fund, whose global origins lay in the initiative of Peter Scott and many European royal families. The Bombay Natural History Society, founded in 1883, comprised British officials, Indian princes and businessmen. The Wildlife Preservation Society of India 1958 was founded by foresters who had a love for wildlife and advocated its protection in an era when shikar was a way of life.

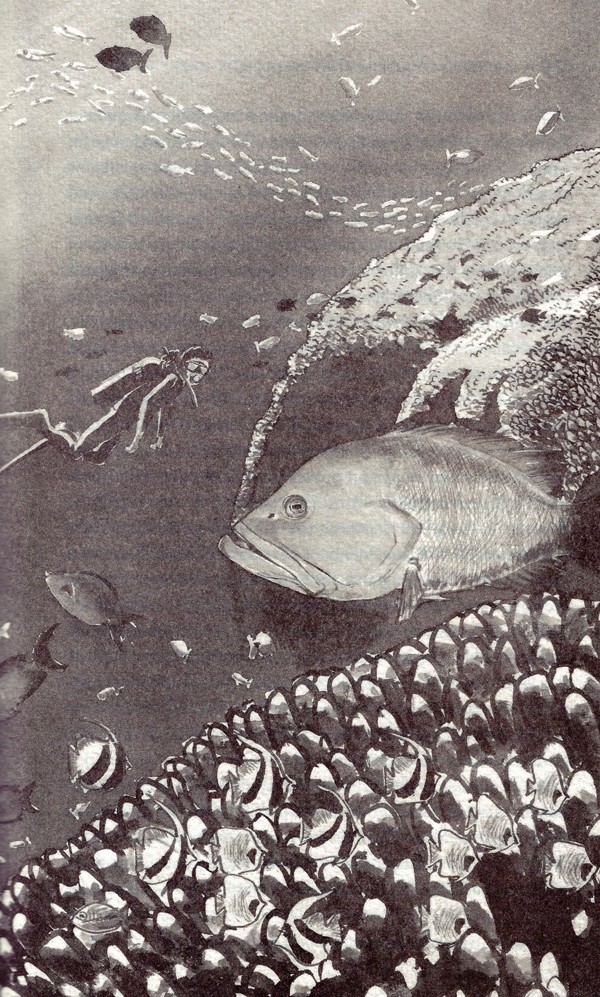

THERE ARE TWO WAYS TO be a student of nature. You can collect, preserve, dissect and describe it, accurate in every sinew and cell. Or you can breathe along with it, engage with its messiness and feel what it feels to be a thing in the world. From both these modes emerge vital truths about nature; of what it is made, what shape it takes and what makes it work. The lessons of the first are precise, replicable and unassailable. Of the second, we are not entirely sure. Its teachings are fuzzy, impalpable, even unreliable. With the first, you can chisel with algebraic purity the results of your enquiry and walk away with the certainty that when you return, an eon from now, those equations will still hold. Not so for the second. Sure, you can still write down all you have seen, thought and felt, but you can never really walk away. The student and the subject are entangled by the very act of observation. This is the wager of being a field ecologist.

The first rule of life is living. Author John Steinbeck, who explored the Sea of Cortez with his marine biologist friend Ed Ricketts, knew this well. Once you commit to being a student of the second kind, once you have sat at the feet of living things, you get to sense 'what every starfish knows in the core of its soul. Like the starfish, Steinbeck says, a true student of nature must proliferate in every direction to the limits of your potential, to leave no direction unexplored.

Steinbeck and Ricketts wandered like starfish along the shores of Baja California more than eighty years ago. The world of nature they inhabited has changed. The space for unbridled nature has shrunk to accommodate the human being's insatiable dreams of growth and progress.

We have seen a similar shrinking in India, too, made even more stark in recent decades. With species and habitats in retreat, we are witnessing a dramatic unravelling of the grand interaction that holds the world together.

Linked as we are to the entanglement, we are part of this unravelling, and it is impossible to merely sit by and watch as the strands come apart. Yet the idea that nature can be somehow bounded within exclusive protected areas, leaving the rest for humans, is a delusion. It misconstrues our place in nature, and nature's relation with the world. This vision of nature ends up limiting how and where nature can exist.

**Contents and Sample Pages**