Chinese Sources of South Asian History in Translation- Data for Study of India-China Relations Through History (Vol-IV- The Golden Period of India-China Relations)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAV336 |

| Author: | Haraprasad Ray |

| Publisher: | THE ASIATIC SOCIETY |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2011 |

| ISBN: | 9788192061504 |

| Pages: | 196 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 340 gm |

Book Description

Subtitled "The Golden Period of India-China Relations" the work contains extremely important data on China, central Asia and India till the middle of the tenth century AD. Of special interest are the personal relations between Emperor Harsavardhana and the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang), the remark of the Indian Emperor after meeting the Chinese pilgrim, details about some of the accounts given by Wang Xuance, the Chinese envoy to India whose written accounts are lost now, as well as the political relations between the states of Kashmir, Tibet vis-a-vis China, and so on.

A must read for scholars and students of ancient and medieval history of Asia.

We are extremely happy to be able to present to the scholarly world the fourth volume of our project which aims at providing data on ancient and early medieval period of India-China relations from hitherto or little known Chinese sources which are both reliable and authentic. This involved the stupendous task of getting at the source materials from the large number of historical and miscellaneous writings in Chinese language in literary style. After selection of these sources-known, little known and unknown-the passages are collated, and then translated and annotated so as to bring out the historical and socio-political significance for the benefit of the inquisitive scholars and students.

In this volume, besides the relevant accounts from the official histories, we have used the additional data from Geng Yinzeng's collection which has initially formed the nucleus of our venture, as well as the volume IV of Zhang Xinglang's collectanea which is the pioneer work on the subject.

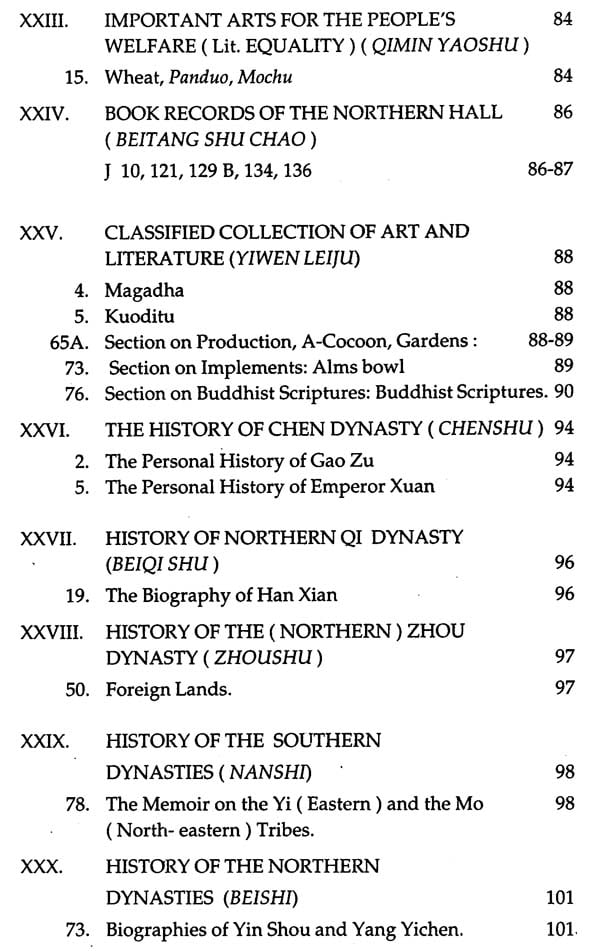

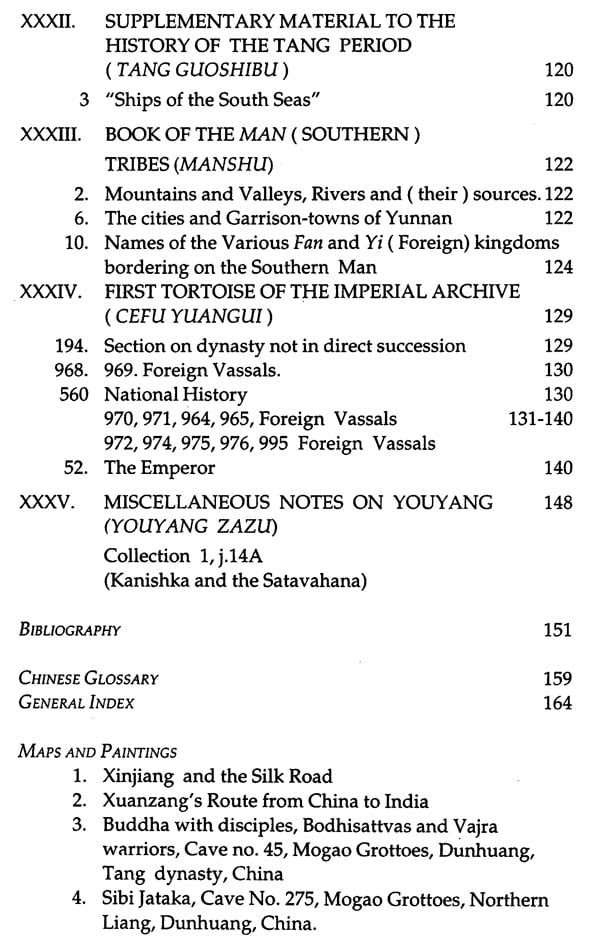

Starting with Liangshu and Suisshu we have tried to accommodate the major works pertaining to sixth century AD through tenth century. However, Cefu Yuangui, completed in early eleventh century during the Song dynasty, has been included in the volume, because it provides important reference materials about the past rulers, particularly the Tang emperors. Total works included are seventeen in number, many of which are translated for the first time.

I may mention here that it is the first time that an attempt is made in India to translate the old Chinese classics like the official dynastic histories as well as the non-official historical and semi-historical writings, travelogues, etc. in search of historical data on South Asian countries like present-day India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka as well as Myanmar and other states of South-east Asia. A lonely man in this exercise, I am trying to grapple with the intricacies of ancient Chinese, unravelling from among the vague and now-defunct expressions, the geographical, historical and other relevant data for the benefit of the concerned scholars and students.

While working on this project, I have the good fortune to consult a profound scholar like Professor B.N. Mukherjee, who, inspite of his failing health, has always suffered me in his reading-room and solved intricate problems of ancient Indian history. My friends like Professor Ge Weijun (CASS) in Beijing has always helped me ungrudgingly. Professor Ma Gang, the former visiting Professor at the Visva-Bharati helped me in translating some of the passages in this volume. I am beholden to the Asiatic Society for all the assistance and encouragement extended to me all these ten years and more in carrying out my work smoothly. I also extend my whole hearted thanks to Mr. Dilip Sen of Datacom for patiently helping me in typing and correction.

We have a sense of relief, a sort of satisfaction, in completing four volumes of the series in a little more than eight years despite limitations like scarcity of resources, tools and library facilities. The translator owns the sole responsibility for all the mistakes and inadequacies that may have cropped up in the book.

I am happy to write the Foreword for the series on Chinese Sources of South Asian History in Translation : Data for Study of India-China Relations Through History, Volume Four : The Golden Period of India-China Relations (6th Century AD-10th Century AD) by Professor Haraprasad Ray. I am very much tempted to quote the following excerpts from the Preface of this volume by Professor Ray : "I may mention here that it is the first time that an attempt is made in India to translate the old Chinese classics like the official dynastic histories as well as the non-official historical and semi-historical writings, travelogues, etc. in search of historical data on South Asian countries like present-day India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka as well as Myanmar and other states of South-East Asia."

I am sure the scholars, and researchers in the area will be immensely benefited by this volume. The Asiatic Society records its deep sense of appreciation to Professor Ray for his scholarly endeavour.

Relations between India and China certainly began with trade, not with Buddhism. The consumption habits of rich Indians were influenced by innovations from Chinas. In this trade silks and silk cloth from the land of China had a special place. The exotic nature of Chinese products was captured in many Sanskrit literary works like Mahabharata, Abhijnana Sakutalam by Kalidasa and Harsacarita of Banabhatta.

While China was enriching the material world of India 2000 years ago, India was exporting Buddhism to China, at least since the first century AD. Hundreds of scholars and translators produced Chinese versions of thousands of Sanskrit Buddhist works. Translations went on with astonishing rapidity.

The period of travail and disunity (220-581) in China coincided with the rise of Buddhism in China and contrasted with the corresponding period of political disunity and decline of Buddhism in India. The imperial Guptas under Chandragupta I, Samudra Gupta and Vikramaditya unified most of North India. The Gupta period was the era of the revival of Brahmanism; Buddhism, due to this revival and later because of Hun invasion from the northwest, gradually started being reduced to non-entity in the land of its birth.

In the meantime, India-China relations continued to flourish. Gupta style Buddhist art spread through the deserts of Central Asia and found its way to the famous cave temples like Yunkang and Dunhuang in China.

In AD 606, when the young Harsavardhana (r. 606, 647) ascended the throne of North India, China reunited under the Sui dynasty (581-618), expanded its power into Central Asia, South-east Asia and Korea. Emperor Wen (r. 581-604) was a great patron of Budhism, and for the first time propagated Buddhism as an "instrument of state policy" (Chen, 1964).3 During his rule, 2,30,000 Chinese were converted to Buddhism, 3,792 Buddhist temples were erected, 1,32,086 chapters (juan) of Buddhist scriptures were copied, and 1,06,580 new statues of the Buddhas were made`. Emperor Wen had thus laid the foundation of what we know as the golden age of India-China relations-the Tang dynasty.

The second Sui ruler Emperor Yang (r. 605-617) almost exhausted government treasury in his ambitious projects like construction of the canal and several war with Korea which led to disaffection among the people resulting in uprising and war. However, it must be pointed out that it was during his reign that in 607, a Japanese envoy, Onono Imoko visited China bearing a letter of introduction. The next year the Chinese emperor sent Pei Shiqing as his envoy to pay a return visit. During that period many Japanese scholars including the famous Takamuko Genri, came to China to study Buddhist scriptures. On returning to Japan, he played an important role in the country's reform drives.

In 617 Li Yuan (r. 618-626), one of the most powerful Sui generals, joined hands with the rebels, and finally overthrew the Sui dynasty. Six months later, he established a new dynasty known as Tang (618-907). The period of politically strong and economically prosperous Tang dynasty was not only the golden period of China, it was the period when the commercial, cultural and political intercourse between India and China as confirmed by our texts, was at its apogee.

During the major part of Tang dynasty China was politically and economically strong, an environment that favoured tremendous development of Buddhism under imperial patronage. Numerous Chinese monks and their Indian counterparts braved the hostile terrains and perilous seas for the dissemination of Buddhism.

Li Yuan, better known under his posthumous name Gao Zu, was succeeded by his son, Li Shimin, commonly known in China as Tai Zong (527-649). One of the ablest rulers of the dynasty, he had to fight against the Turkish menace from the West and the North. He won them over either through military defeats or diplomacy. The Chinese supremacy was once again restored in different parts of Eastern Turkestan (Xinjiang), namely, Kucha, Karasahr, Khotan, Kashgarh and Yarkand (Suoju). Friendly relations were established with Samarkand, Bokhara and Kashmir. Tibet had risen into political eminence in this period. The matrimonial alliance could not prevent Tibet's conflict with China and the neighbouring countries, specially over both the Palur (Bolu) states in the southern Hindukush region. Our records translated in the following pages provide us a glimpse into this political spectrum in both the Tang dynastic histories as well as other texts like FYZL, CFYG, etc.

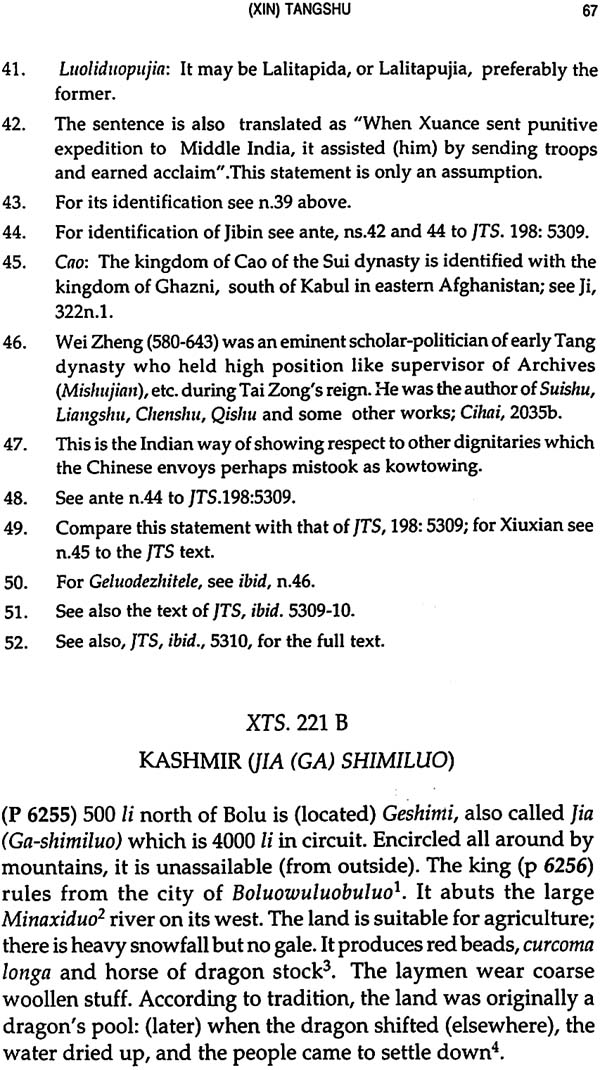

Chinese diplomatic exchanges with South India also assumed significant dimension in this period, especially during the reign of Narensimha Pota Varman. Jibin (Kapisa, around Kabul region of today), and Kashmir (present-day Srinagar area) under Chandrapida, Muktapida and others were also in intimate contact with China at the time in question (texts translated from JTS, XTS, XTS, CFYG etc. may be referred).

Tai Zong's successor, Gao Zong (r. 650-683) somehow retained authority over the conquered territories. He also annexed Korea to the Chinese empire. His widow, Wu Zetian, succeeded to the throne in 684 and reigned till 704. A very able ruler, she put down effectively the political troubles in the Xinjiang area.

The emperor Xuan Zong succeeded to the throne in 712, and enjoyed a long reign till 755. He was as great a ruler as Tai Zong. He suppressed the political unrest in various parts of Central Asia and restored the political supremacy of China over these kingdoms. He also established political relations with the neighbouring kingdoms, and carried out brisk diplomatic exchanges with them throughout his reign. Our texts bear witness to his inter-state intercourse recorded in detail specially in CFYG. After Xuan Zong's death political decadence set in leading ultimately to the downfall of the Tang dynasty. And here ends the story in this volume.

In the following pages we shall bring our readers face to face with leaders of men, the rulers, officials, the missionary-monks, both Indian and Chinese, and official historians. They will find themselves in the midst of unprecedented growth of Buddhism in China, and expansion of diplomatic and trade relations between South Asia and China.

**Contents and Sample Pages**