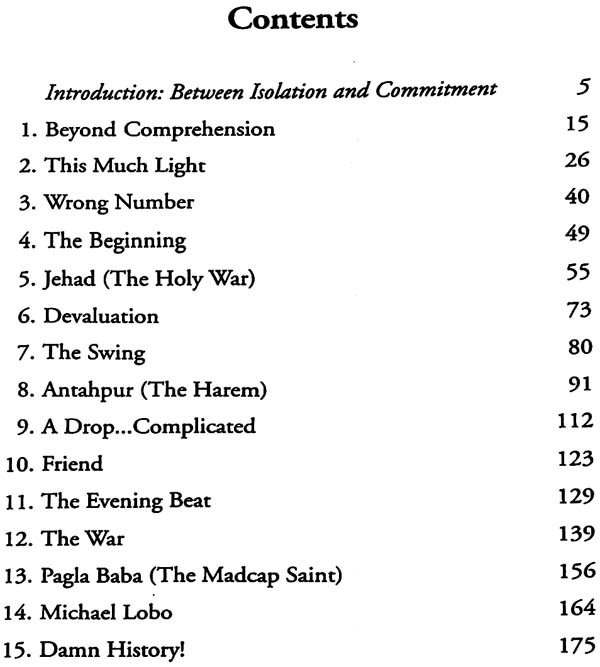

Damn History (Collection of Short Stories)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAQ475 |

| Author: | Govind Mishra |

| Publisher: | Ocean Books Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9788184303308 |

| Pages: | 184 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 300 gm |

Book Description

" So said Nirmal Verma about Govind Mishra's short stories. Another prominent short story writer of Hindi Shailesh Matiyani opined — 'Even though writing on both the worlds — the inner and the outer — Govind Mishra saved himself from the dangers of both realism and romanticism. That way he comes to belong to the tradition of not so much Jainendra, Ajneya or Nirmal Verma but that ofPremchand.'

Having created more than a thousand characters in his fiction, Govind Mishra's portrayal extends from villages, to towns, to cities, to metros and even up to foreign melieu. 'Few writers have such a big range' said Srilal Shukla of Rag Darbari fame.

`Damn History' attempts to present in English for the first time, representative stories of the author, selected from more than fifteen collections or his short stories in Hindi, 1965 onwards.

Govind Mishra, renowned Hindi novelist and short story-writer. Acclaimed in the Hindi world both for the quantity and quality of his literary output, he has till this day over fifty books to his credit including eleven novels, more than one hundred fifty short stories, five collections each of travelogues, and literary essays and one collection of poems. Of the numerous awards, he has received over the years, the prominent ones are — Vyas Samman (1998) for the novel `Paanch Aanganowala Ghar', Subramanya Bharti Samman (2000), Sahitya Academy Award for the novel `Kohre Mein Kaid Rang' (2008), Bharat Bharti (2011) and now the most prestigious Saraswati Award (2013) for Dhool Paudhon Par'.

The novel `Paanch Aaganowala Ghar ' has been published in English as 'House With Five Courtyards' by Penguin and `Kohre Mein Kaid Rang' in English by Sahitya Academy. His works have been profusely translated in other Indian languages as well.

Between Isolation and Commitment

The generation that came of age in post-1947 India finds something deeply frightening, almost nightmarish about the world it inhabits. Exposed in childhood to a frenzied idealism all around, it grew up into an atmosphere of temporary euphoria before disillusionment set in. Subjected to such different emotional vicissitudes in such a short time span, this generation has lost its capacity to be certain about things. It cannot share the smug regret of the older generation about the crisis of character that is supposed to have set in. Nor is it comforted by the younger generation's belief in what is called the total revolution. Shibboleths, slogans and propaganda leave it equally cold. Yet its uncertainty is different from the scepticism that is merely an intellectual acquisition. The groping souls that comprise this generation, when they decide to write, are often misunderstood and maligned for their lack of commitment.

But commitment in some of these cases may take the form of a concern for the man as a man and the society of which he is a part, and insofar as it transcends dogma, it may be a more genuine, though less definable commitment. This explanatory statement can command only the limited validity of a generalised observation. Also, it is subject to the constraint that no individual ever truly typifies a group. And yet there is something in the output of Govind Mishra that induces, and confirms, such a generalisation about his generation.

Deceptively simple in his choice of words and structure, Govind is a difficult writer to write about. More so because he is constantly moving on from one experience to another, from one theme to another, defying all labels at a time when labelling and grouping have become virtually indispensable for survival in the Hindi literary world which is politicised in the worst sense of the term. Govind has written about a variety of human situations that is remarkable.

What is more remarkable is an acute, cold passion of treatment that he seems to have acquired over the years. In Naye Purane Maa Baap, his first published short story, Govind uses a child to recapture the romantic sentimentality of a sad adolescent love; the writer is puerilely a part of the narrative. This mood makes its obstinate appearance in many passages of Utarti Huyi Dhoop, his second novelette. Perhaps the reason lies in the intensely personal theme chosen by Govind. But there is also a tension, a struggle to wean the writer away from the `I'. The use of the third person in the narrative does help resolve the conflict, but only partially. It is, rather, the treatment of the theme, and the act of writing the novelette, that makes the weaning possible. You may have to relive your past to be emancipated from it. Not that reliving necessarily leads to liberation; it may become an obsessive passion.

The world, as it were, began thereafter to reveal itself to Govind. The others began to appear as real autonomous beings; the others as they saw themselves and as the writer saw them. So did the specific 'universe' in which these others and the writer moved. Perception became a consciously tricky process. The writer began to grope, and to chasten. Aloofness and involvement began to co-exist, though in ever-varying proportions.

Soon, Govind Mishra reached a point where he could, with a successfully subdued passionate objectivity, capture situations that reveal the abiding and changing aspects of a man's internal and social reality in a complex, fluid 'universe'. Of course, this cold passion often makes way for a particular mood in which the writer happens to react to a given situation: it may be boredom, resignation, pathos, desperation or cruelty. These are passing moods. The increasingly dominant note is that of analytical description where the passionate involvement of the writer quietly and tenderly gives a particular piece its unity, while his abiding sense of uncertainty lets the others appear as real, and prevents him from passing judgement which seems to have become an essential characteristic of 'committed' literature.

‘Jehad' may be cited as an example. The progressive devaluation of man in modern life and his frantic attempts to maintain his dignity appear as refrain in many short stories of Govind Mishra. This trend is particularly noticeable in the world of Indian bureaucracy, a theme dealt with by Govind in his first novelette, appropriately entitled Woh Apna Chehra. The loss of a blooming, idealistic personality is as unequivocal as the resultant lapse into a patterned, corrupt one. Ending on a note of somewhat petulant submission to the fated anonymisation, Woh Apna Chehra betrays a variety of moods from anger to frustration. Not so Jehad'. Delineating with understanding and brutal restraint, the inevitable fate of a determined 'crusade' against the Procrustean system, it marks the first major success of Govind in the exercise of passionate objectivity. Having nursed his idealism in the relatively protective atmosphere of the university, the young man has joined the administrative service of the government with a determination to root out the corruption around him. The aggressiveness of the crusade soon begins to fade, as does the glow of idealism. Drawn into the vicious whirlpool of humiliation and defeat, the young man retains the illusion of crusade; perhaps the realisation of having compromised would make him hate himself. Man ordinarily does not want to be deprived of the sustenance provided by self-righteousness. In the tussle between selfishness and the `mission', the young man goes on making compromises, invariably at the expense of the mission, but with a shrewdness that would postpone a confrontation with the reality. Reading jehad' you feel the intensity of this tragic personal and social drama. But in the narrative, there is not the slightest attempt to judge either the man or the society. There is only the attempt to understand, a terrifying exercise indeed.

If the young man ‘ Jehad' makes the inevitable compromise, the overseer in Ankade' (Statistics) takes the fight to a more logical point where he is pulverised by a code of law which has been devised to maintain the status quo, and which would have nothing to do with justice. But Govind Mishra retains his impassivity. It seems as meaningless to shower encomium on the stouter-nerved overseer as it was to condemn the young entrant into the administrative service of the earlier story.

Once it has begun—irrespective of whether the individual realises or ignores this reality—the process of compromise ruthlessly inflicts revenge on man. And there is no escape from the process. It injects a poison that kills slowly and in a variety of ways. In Dost' (friend), Avamulyan' (devaluation), Seedha...Door Tak Seedha' ,` Baandh' ,Dhalaan' and `Ghaav' , to mention a few examples, Govind Mishra deals with situations where interpersonal relations are losing their depth, though the urge for such relations has lost little of its intensity. The continuing desire of man for human intimacy and his increasing inability to achieve it are, it seems, becoming the destiny of modern man. While dealing with these situations, Govind is particularly concerned about understanding the ways in which the quality and the pattern of individual life are subtly, almost unconsciously, affected by the reality of social life. In his usual deceptive style, he exposes aspects of human life where normal human urges and emotions have been so curbed and controlled by the external compulsions of survival that even under terrible emotional stresses, the reflexes of these victims of circumstances cannot recapture their spontaneity. Commercialised sex by a wife with the cognisance of her husband; resigned submission of a friend in government service to the abuse of his position by a businessman friend; the frantic effort of a father to delay the marriage of a daughter on whom he is dependent not only economically but also for an incestuous satisfaction derived from physical proximity (with the latter statement, Govind Mishra may have some difficulty in agreeing, though he will concede that his is not necessarily the correct interpretation), commitment to a projected revolution and subsequent betrayal, and so many other themes are taken up by Govind in the same spirit of passionate detachment.