Double Talk

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDE671 |

| Author: | Manjula Padmanabhan |

| Publisher: | Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2005 |

| ISBN: | 9780143032663 |

| Pages: | 102 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 7.0" X 8.0" |

| Weight | 260 gm |

Book Description

From the Jacket:

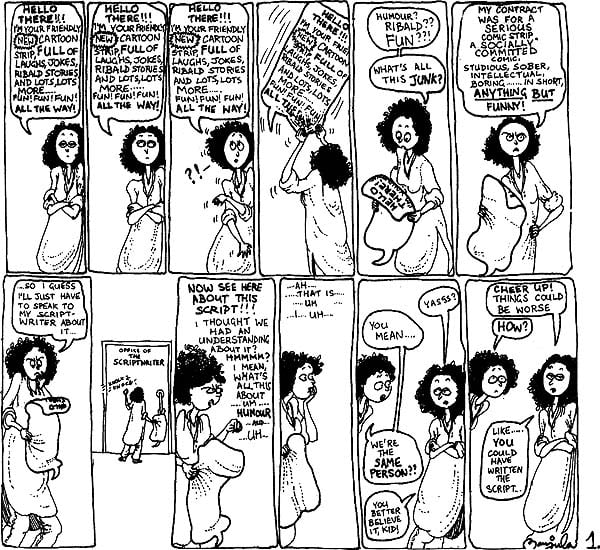

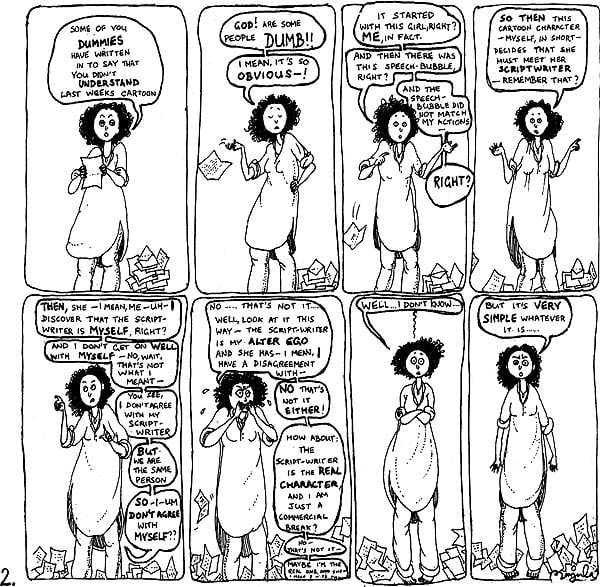

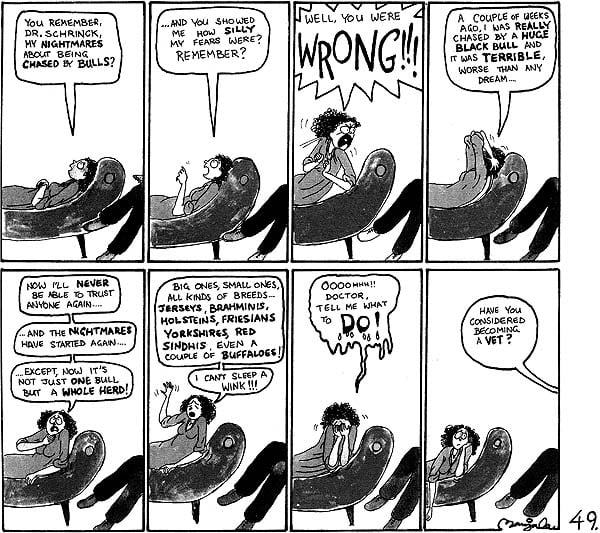

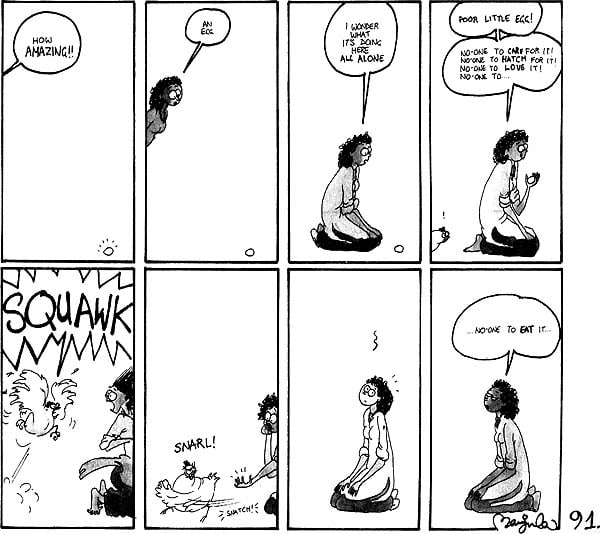

'Double Talk' first appeared in the Sunday Observer in Bombay, 1982. Suki, its central character, was a bushy-haired, baggy-clothed free spirit. With neither job nor family to tie her down, her life was uncluttered, unencumbered and always unconventional. In four years, she had just one romance, and her best friends were non-human. In the nineties, Suki was resurrected in a daily strip of that name, in the Pioneer in New Delhi, where it ran for six years. Despite all the changes that have occurred in the real world since Suki's birth, the character and the illustrations continue to bristle with their own quirky brand of humour - or lack of it: Bombay's feisty readers had strong views about the cartoon, and sent it close to sixty letters of complaint to the editor!

This book represents a selection of the strips that appeared in print between 1982 and 1986.

About the Author:

Manjula Padmanabhan (b. 1953) is a Delhi-based writer and artist. Her comic strips appeared weekly in the Sunday Observer (Bombay, 1982-86) and daily in the Pioneer (New Delhi, 1991-97). Her books include Hot Death, Cold Soup (Kali for Women, 1996), Getting There (Picador UK, 1999), This is Suki! (Duckfoot Press, 2000) and Kleptomania (Penguin Books India, 2004), Harvest (Kali for Women, 1998 and subsequently in three separate international anthologies), her fifth play, won the 1997 Onassis Award for Theatre. Manjula has illustrated twenty-four books for children including her own novels, Mouse Attack and Mouse Invaders (Macmillan Children's Books, UK, 2003, 2004).

Suki's story begins in mid-1982, in the pages of Bombay's Sunday Observer. She was twenty years old, sassy and unruly. Though she started out as my alter-ego, she quickly established her own persona: while I struggled to support myself on my earnings as a freelance illustrator and occasional journalist, she was mostly unemployed; I lived precariously as a paying guest, while she paid little attention to money, household chores or any other practical matters. In fact, it was Suki who paid my rent by ensuring a trickle of income every month.

The strips in this book represent two-thirds of those that appeared in print during Suki's Bombay years. I will always be hugely grateful to Vinod Mehta, founder-editor of India's first Sunday newspaper, for being so generous towards her. He put up with her antics with no complaint, from her scruffy early drawings to her always panicked last-minute arrivals at the press, and placed no restrictions on what she said, did or looked like. Such freedom is rare in journalism. It tremendously boosted my confidence as a cartoonist and illustrator.

Seeing these strips in sequence now reminds me of how much Suki changed between the first strips and the last, in late 1986. The early frames are packed tight with details and I used a .02 Rotring pen to write the speech bubbles, making the text almost impossible to read. But then the paper began to introduce colour sections. I could no longer produce the strips on time if I wanted to maintain the same level of detail. Meanwhile, the discipline of having to meet my deadlines every week gradually resulted in a drawing style that was smoother and more precise. Rather than draw the frame-lines free-hand, I used a ruler toget them straight: as so many well-organized people had discovered before me, 1 found it was actually quicker to do them neatly than to be careless and untidy. I used a thicker gauge of pen-nib so that I could do the colour-filling more efficiently. The whole drawing became bigger and clearer.

People always used to ask, 'Where do you get your ideas from?' My answer then as now, when I'm asked the same question in reference to short stories, is that I don't go looking for material. I use whatever is close at hand, from events around me, from the daily newspaper, from conversations with friends. Some of the characters in the strip were based directly on my buddies: Gautam and Anvar, for instance are real people, and they still look quite a bit like their cartoon selves.

In December 1992, Suki enjoyed a revival in the form of a daily strip in the Pioneer) New Delhi. The editor, Vinod Mehta, once more welcomed Suki to his pages, offering her top billing in the stack of strips appearing at the back of the paper. Delhi's readers were very different to Bombay's, however: more conservative, less comfortable with colloquial English. While Bombay's readers sent in about 60 letters, many of them complaining that the strip was boring, humorless and unpalatable, Delhi's readers remained silent throughout the strip's six-year run.

I'm often asked why I don't revive Suki, why there are so few indigenous comic strips in India, why there aren't more women cartoonists. My constant response is that the problem isn't one of supply or of gender discrimination, but DEMAND. Unless local strips are actively critiqued and appraised by their readers, local cartoonists will remain minor curiosities, never becoming the pop-sociologists that the best international strip cartoonists are. More than anything else, cartoonists need engaged and intelligent readers. Just like the one who's reading this book right now!