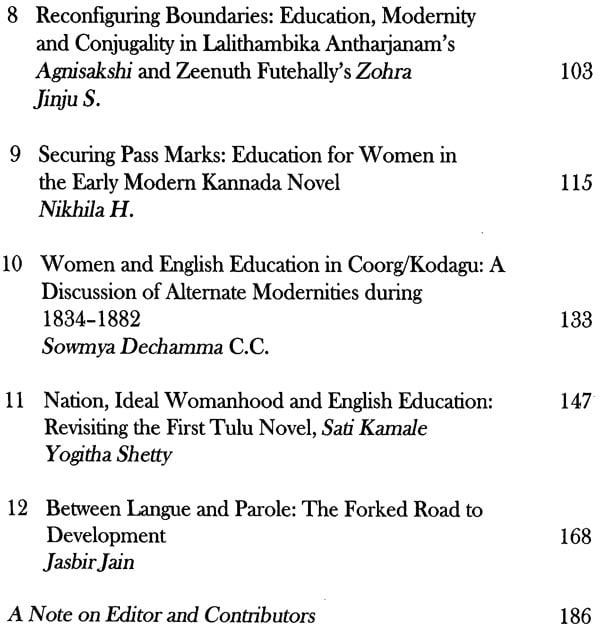

Influence of English on India Women Writers: Voices from Regional Languages

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAQ533 |

| Author: | K. Suneetha Rani |

| Publisher: | Sage Publications India Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2017 |

| ISBN: | 9789381345153 |

| Pages: | 222 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 200 gm |

Book Description

KAMALA DAS, a well-known woman writer in English and Malayalam, proclaims in her poem 'An Introduction':

I speak three languages, write in Two, and dream in one. Don't write in English, they said, English is Not your mother-tongue. Why not leave Me alone, critics, friends, visiting cousins, Every one of you? Why not let me speak in Any language I like? The language I speak, Becomes mine, its distortions, its queerness’s All mine, mine alone. (2004: 62)

This proclamation of choice and condemnation of restrictions on writing in English marks an inheritance of a long history of debates around English in India, especially in the context of women's voices and issues. English was not just a language, a medium of instruction and a colonial heritage but it also signified manners, lifestyle, politics and modernity. Rajeswari Sundar Rajan, in her introduction to her book The Lie of the Land (1993: 8) says, 'the disciplinary formation of English in India therefore needs to be contextualized within at least three broad areas: its history, language politics, and the socio-cultural scene of education. By framing it within these larger issues-which, in a sense, provide the fixes for its location-we are also enabled to see from where resistance to it is mounted, and what forms it takes'.

While it is true that the disciplinary formation of English in India, as Sundar Rajan observes, needs to be contextualized within at least three broad areas of its history, language politics, and the socio-cultural scene of education, the non-academic/popular (people’s) field of English also needs to be contextualized at least within the above three broad areas. In the academic as well as the non-academic forms/fields of English, gender played a crucial role liter-ally and metaphorically. The beginnings of the English discourse in India in the nineteenth and the early twentieth century’s, as many critics have observed and argued, seems to have been built majorly around the category of gender. Such discourse also presented con-tradictory approaches to the English argument, but they were all intricately connected. English helped in molding better family women; English provided a garb of modernity to reiterate traditional gender stereotypes; English contributed to the creation of the world of dichotomies but English also created a hope for the outcastes deprived of entry, education and employment.

Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid in Recasting Women (2010: Introduction) discuss the differentiation of language patterns by referring to William Carey, the Baptist missionary who was involved in the Orientals restoration project. He produced with the help of Indians a reader in 1801 for the students of Fort William College. It was a compendium of sketches of various castes and classes and depicted the idiomatic language, manners and customs of women, merchants, fishermen, beggars, labourers and attempted to repro-duce their speech patterns. According to this compendium, linguist-tic sophistication was proportionate to social status. Women were identified as low caste through the vulgarity of their speech while the vocabulary of higher caste women was represented as a mixture of refinement and vulgarity. The difference between vernacular and the genteel Bengali extended/represented women and men also in terms of their status even within the same family (ibid. 12-13).

The 1801 compendium not only tried to depict the linguistic scenario but also tried to define and describe the low-caste and the high-caste women based on the language that they used. Such descriptions extended to gender identities as well. It clearly made a statement about gender when it said the upper-caste women used language that was a mixture of refinement and vulgarity. Probably refinement represented their class while vulgarity represented their gender, which was common between the women of lower castes as well as the higher castes according to the compendium. The conflict between English and the Indian languages or the co-relation between the two, given their political and other statuses, began to be identified in terms of gender. As Shefali Chandra observes in her article `tendering English' (2007: 289), the masculinity of English was being constantly accompanied by the feminization of the vernacular. This article focuses on the representation and regulation that shaped the context and reach of Indian English, which is the process forming its own language of gender. The author says that `this gendered English created new codes of signification to support the matrix of colonial-national and heterosexual gender'.

English was viewed as a colonial legacy, which it was. It was also looked upon as an endorsement of colonization and the anti-English stand was considered decolonizing. People questioned, debated, adopted, manipulated and mastered over English but on the other hand admired it, followed it and owned it. English as language, education and culture was inevitably connected to education in the case of women. Jasodhara Bagchi (1993) goes a step forward to under-stand how the emphasis was shifted to sishukanya, the girl child, to mould women. She writes that education for and of girls became a recurrent theme in the writings of the nineteenth century. There was a steady growth of women's education in Bengal from the time of Vidyasagar. Education was considered to be a social space that could provide status and empowerment for women. On the other hand, there was resistance to school education for girls due to the deep rooted fear of early widowhood. Western education became a characteristic feature of the men of the rising middle classes while the girls had to face number of hurdles. Added to that, English/western education was supposed to be encouraging women to become immodest, undisciplined and un-controllable.

Education, particularly women's education, was, and still is, a major issue in India. Modem Indian literatures have discussed

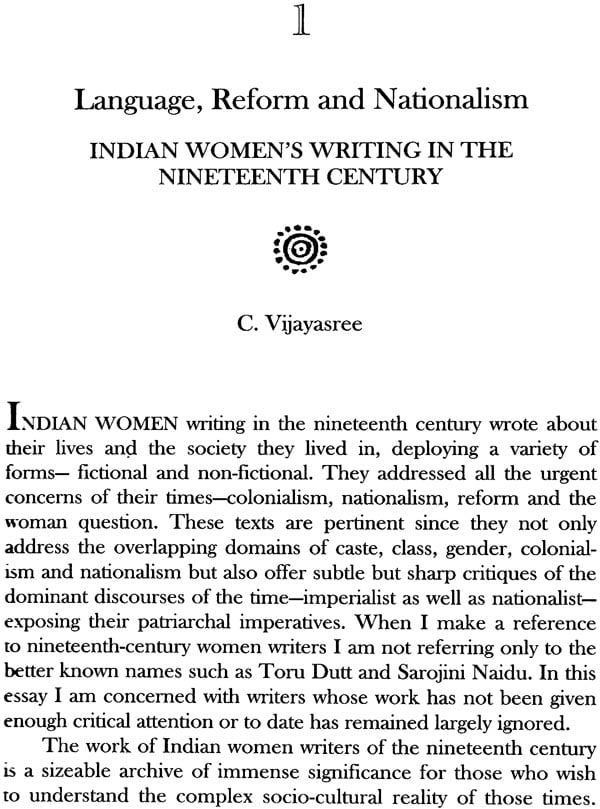

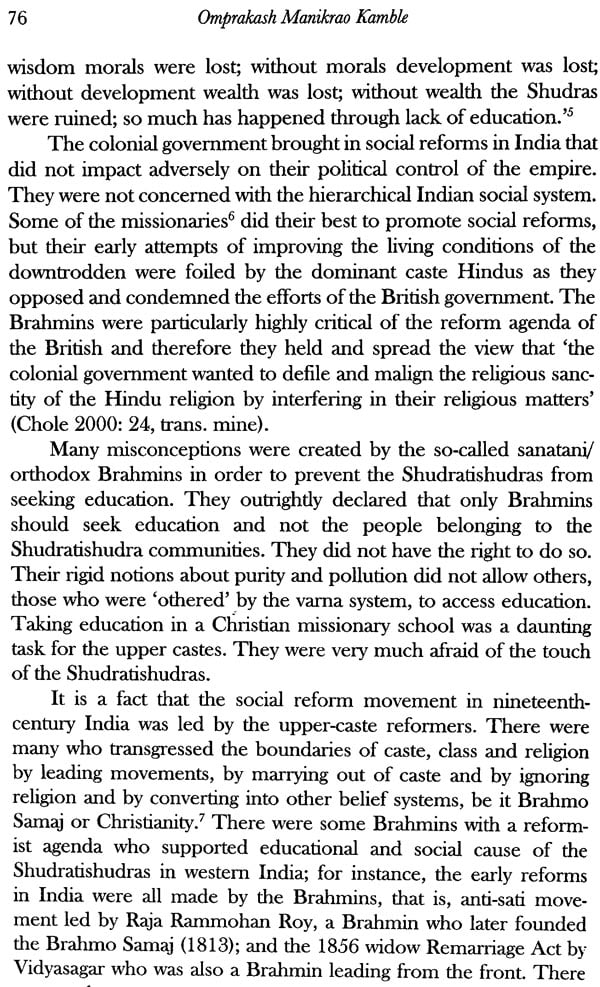

Book's Contents and Sample Pages