Inquilab (Bhagat Singh on Religion and Revolution)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAS217 |

| Author: | S Irfan Habib |

| Publisher: | Sage Publications India Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9789352808373 |

| Pages: | 218 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 250 gm |

Book Description

S Irfan Habib is an eminent historian and former professor, National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, New Delhi.

Extolled for his extraordinary courage and sacrifice, Bhagat Singh is one of our most venerated freedom fighters. He is valourised for his martyrdom, and rightly so, but in the ensuing enthusiasm, most of us forget, or consciously ignore, his contributions as an intellectual and a thinker. He not only sacrificed his life, like many others did before and after him, but he also had a vision of independent India. In the current political climate, when it has become routine to appropriate Bhagat Singh as a nationalist icon, not much is known or spoken about his nationalist vision. Inquilab provides a corrective to such a situation by bringing together some of Bhagat Singh's seminal writings on his pluralist and egalitarian vision. It compels the reader to see that while continuing to celebrate the memory of Bhagat Singh as a martyr and a nationalist, we must also learn about his intellectual legacy. This important book also makes a majority of these writings, hitherto only available in Hindi, accessible for the first time to the English-language readership.

It is my pleasure and privilege to write a preface for a book, which is different from all others I have done before. It is not merely an academic exercise but an emotional and socio-political one. My own association with Bhagat Singh and his comrades goes back to forty years. It began merely as a young researcher's quest to explore the fresh and obscure dimensions of their revolutionary struggle, but Bhagat Singh has since remained a passionate ideological presence in my life.

It is a socio-political one because Bhagat Singh was committed to Inquilab or revolution but it was not merely a political revolution he aimed at. He wanted a social revolution to break the age old discriminatory practices. However, most of the eulogies have ignored his social programme, projecting him merely as an ardent anti-colonialist and nationalist, which is not inaccurate, but incomplete. Bhagat Singh going to the gallows as a nationalist is not something exclusive to him alone, two others were hanged with him and many more were hanged before him as nationalists. He is different because he left behind an intellectual legacy, a huge collection of political and social writings on burning issues of even contemporary importance like caste, communalism, language, and politics.

This book Inquilab: Bhagat Singh on Religion and Revolution is a collection of some of his writings which will further establish him as a political thinker. It is significant to read what Bhagat Singh wrote in the 1920s, particularly in the midst of seething university campuses and the spread of exclusivist politics today.

This book is not just another one on Bhagat Singh, which will celebrate him as a martyr, as most of them have done all these years. We need to establish here that Bhagat Singh was more than that, he was a prolific writer, an insightful thinker and a sensitive young nationalist who left behind a rich intellectual legacy to ponder about. During the past few years we have had a good collection of his writings in Hindi but a more exhaustive collection in English was not around. Some of his important English writings are available, which we have included here as well, but several of them brought in here are not available to English readership. This book attempts to fill that serious void.

There is no doubt that Bhagat Singh is one of the most celebrated martyrs of the Indian freedom struggle. He has left behind a legacy that everyone wants to appropriate, yet most do not wish to look beyond the romantic image of a gun-toting young nationalist. Perhaps the reason is that this is the image that was created in the official colonial records, an image we inherited and conveniently accepted as truth. Colonial records told the common masses that revolutionary activities were dastardly crimes, committed for the gratification of money and blood lust. In fact, this is clearly reflected in the contemporary consciousness, particularly that of the youth, who visualise Bhagat Singh as someone who terrorised the British through his violent deeds. His daring spirit is lauded, turning him into an icon. His posters are sold on pavements, stickers with his photo dot car windscreens. It may be heartening to see that Bhagat Singh is still loved and venerated but the question we need to ask is: do we have any clue about his politics and ideas? Even his early faith in violence and terrorism was qualitatively different from the contemporary terrorist violence. He soon transcended even that to espouse a revolutionary vision to transform independent India into a secular, socialist, and egalitarian society. He conceded in his writings that he may have pursued terrorist methods in the beginning of his revolutionary career but soon realised the significance of mass mobilisation and importance of the youth, workers and peasants. He declared in one of his last messages from prison, included here in the book `that I am not a terrorist and I never was, except perhaps in the beginning of my revolutionary career. And I am convinced that we cannot gain anything through these methods.'

He is undoubtedly an icon who is venerated across South Asia. Just a few days ago, even Pakistan called Bhagat Singh a shared hero between the two countries. During my few visits to Pakistan, I always found huge popular support among the people there, who lauded him for his ultimate sacrifice and for the ideals he espoused. What is refreshing now is the acknowledgement of this fact from a high government official, who categorically declared that 'Bhagat Singh was the Independence movement hero of both India and Pakistan. The people of the country have the right to know about his (Singh) and his comrades' great struggle to get freedom from the British Raj."

Bhagat Singh is probably the only one after Mahatma Gandhi who evokes such unbounded awe and respect. This could happen because his appeal as a martyr cuts across political ideologies. I only wish that the same was true for his intellectual legacy as 0 well. Most of us just lap him up as a martyr, but very few celebrate his political and social vision. I don't mean to undermine the sacrifice of Bhagat Singh or any martyr for that matter, but will add that he was not just a shaheed. We do great injustice to his memory when we extol him only as a martyr. Bhagat Singh left behind a corpus of political writings underlining his vision for an independent India. This little book is a collection of his writings, mostly those which bring him out as a serious chronicler of his times, commenting on several topical issues.

Bhagat Singh was a keen observer of everything happening around him, not letting anything of consequence pass without a comment. He had a short life but with an advantage that he began to read and write very early. He also had an advantage of being born in a family of committed nationalists. His uncle Ajit Singh was involved with the peasantry, founded the Bharat Mata Society and spent most of his life in exile, fighting against imperialism. His other uncle Swaran Singh spent many years in prison and died young due to tuberculosis. Bhagat Singh's father Sardar Kishan Singh was an active Congressman who also spent time in British jail. Given this background Bhagat Singh evolved early as a political being, maturing fast into a serious revolutionary thinker and commentator.

This somehow explains why Bhagat Singh evokes such boundless approbation from people who already have a surfeit of heroes. When most senior leaders of the country had only one immediate goal-the attainment of freedom, Bhagat Singh, hardly out of his teens, had the prescience to look beyond the immediate. He was no ordinary revolutionary who simply had a passion to die or kill for the cause of freedom. His vision was to establish a classless society and his short life was dedicated to the pursuit of this ideal. Of course a political revolution-removing the British-was the first step to effecting any kind of social programme, but removing the British has been popularly presumed to be the sole aim of Bhagat Singh's politics.'

This book of Bhagat Singh's writings is not exhaustive but is surely representative of his mature intellectual evolution and his sensitivity to most of the complex issues which remain pertinent even now. We have also included here manifestoes, statements, pamphlets and other such writings, which had the stamp of Bhagat Singh's ideological approval. In the end, we have incorporated some insightful excerpts from his prison diary, which can be seen as the culmination of Bhagat Singh's intellectual evolution.

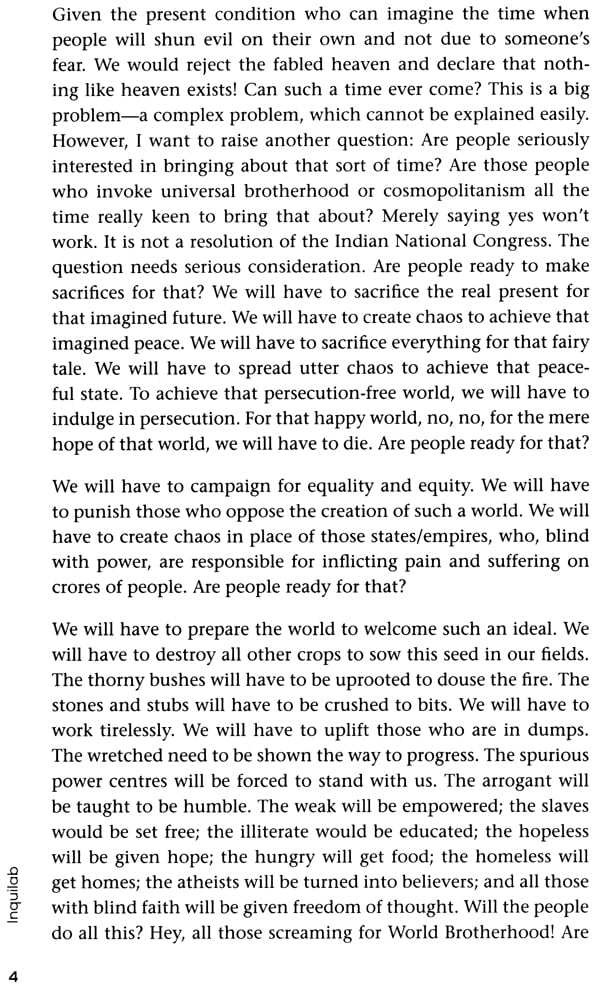

As I have pointed out before, Bhagat Singh began writing early in life. One of the articles used here was published in 1924, when he was just 17 years old, and it was on Universal Brotherhood, not a very easy subject to write on at such a young age. It is rare to find a young man conceiving an idea of universal brotherhood and articulating it in a detailed article. He imagined a world in 1924 where 'All of us being one and none is the other. It will really be a comforting time when the world will have no strangers.'3A11 those who are busy othering and creating strangers out of their own fellow citizens need to grapple with Bhagat Singh's views, instead of merely glorifying him as a martyr. He goes further to say something which should be remembered by all in India and Pakistan, if at all we accept him as our shared hero. He emphatically exclaimed that 'As long as the words like black and white, civilised and uncivilised, ruler and the ruled, rich and poor, touch-able and untouchable, etc., are in vogue where is the scope for universal brotherhood? This can only be preached by free people. The slave India cannot refer to it.' He goes further to appeal that, 'We will have to campaign for equality and equity. Will have to punish those who oppose the creation of such a world.' Perhaps he was the only one among the heroes of our freedom struggle who had this vision at such a young age.

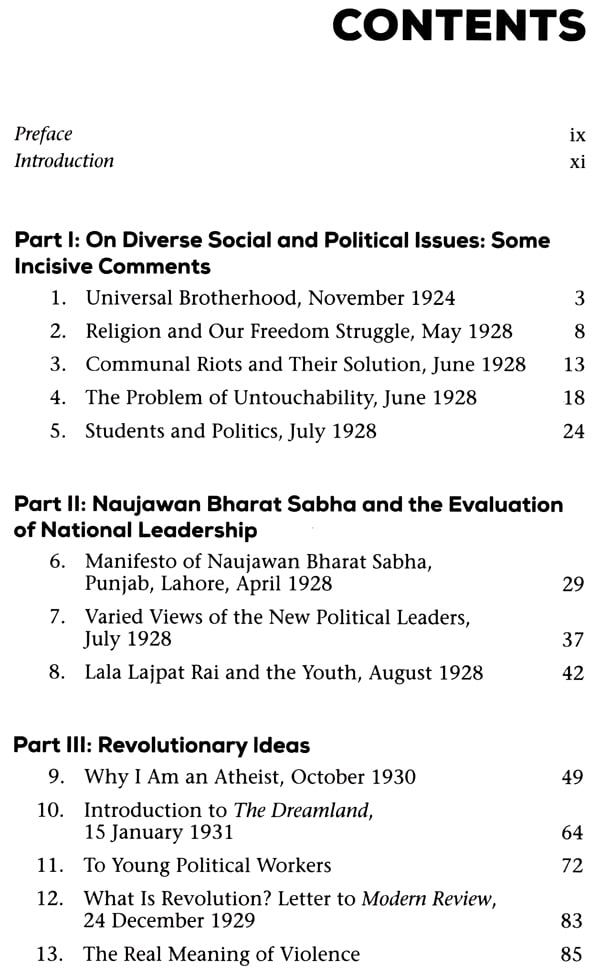

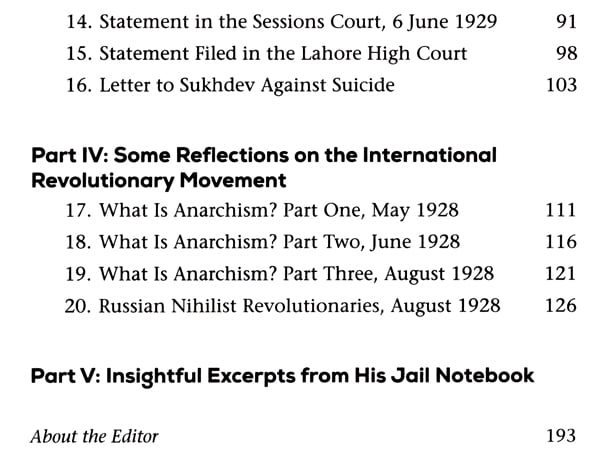

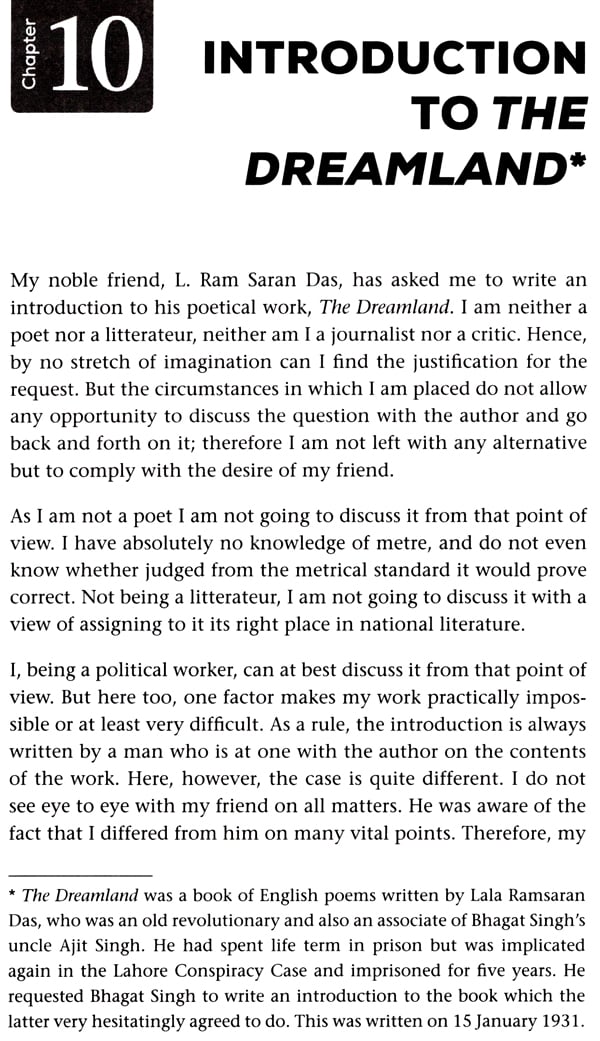

**Contents and Sample Pages**