Nyaya Sudha of Sri Jayatirtha (Second Third and Fourth Adhyayas)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM777 |

| Author: | Dr. B. N. K. Sharma |

| Publisher: | Vishwa Madhwa Maha Parishat, Bangalore |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2001 |

| Pages: | 158 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 190 gm |

Book Description

Divergence of views among purely speculative systems' of philosophy is generally due to ideological predilections which are mostly subjective. But systems of Vedanta developed in India in the medieval period are bound by their sworn loyalty to a body of revealed Texts, which restricts free movement of thought and force system builders into various ways of interpretation to make both the ends meet.

The Mimamsa Sastra has developed canons of interpretation of Sastra texts to determine their import, such as their commencement, conclusion, repetition, erttieveo: and sound reasoning (upapatti).

The fact that all system builders of Vedanta have been obliged to produce their own commentaries on the Sutras of Badarayana makes it clear that they hold the master key to the understanding of the import of their source books - Vedantavakyani hi Sutrair udahrtya viceryante. Vedantakusumaqrathanarthatvat sutranarn (S.). This makes it clear that the Sutras constitute the Vicara Sastra and their basic texts the Vicarya Sastra. In other words, the source materials of the sutras are the Nirneya Sastra and the Sutras their Nirnayaka sastra as in the case of the text of the Law and its interpretation in our Legal parlance - Sabdajatasya sarvasya yatprarnanasca Ni rnayah - as M. puts it.

This should make it clear that the Upanisads which according to S. are the sole sources of his Aupenisedem dersenern, must abide by the findings of the Sutrakara. But this is nullified in S's way of interpreting the sutras on so many crucial occasions, by defying and setting aside the findings of the Sutrakara, as at the very outset in the Anandarnayadhi. saying :

Idam tviha vaktavyam. SutraQi tu evam vyakhyeyani,

Sruti sutrayor virodhe SutraQi anyatha neyani.

Accordingly, he identifies all the five members of the Annamaya series as Kosas, material sheaths of the embodied self and elevates the Puccha Brahman as the Nirvisesa, as we have seen in Vol. 11 (pp. 15-52).

He sets great store on the essential oneness of the self of the embodied Jivatrnan with the Supreme B, at the very outset of his Adhyasa - Bhasya with the proposition Atma ca Bretime, despite Sutrakara's defining his B to be investigated, as the Author of the universe (I. 1. 2) which role he (S.) assigns to his duplicate B. - the Saquna. However, it deserves to be noted that according to the Sutrakara, B's authorship of the universe includes not only the external material world, but all the dispensations in the life and career of the Jivatrnans, their genesis and vicissitudes in life in all states, the obscuration of their Svarupa-Jnana, ananda etc. in Sarnsara by Bhavarupa ajnana, its removal and Liberation of souls by Divine grace, as explicitly stated in Sutra III. 2.5.

Had the Sutrakara intended to uphold the essential identity of Jiva and B. he would have worded his opening sutra as Athata Atma Jijnasa or Atmano Brahmatva - Jijnasa, putting his cards on the table. Instead, he makes it clear in the Dyubhvadyadhi. (I. 3. 1-8) based on MU09aka Up. (11. 2.5) that the term Svasabda in the Sutra standing for Atrna-sabda in the MU09aka, refers only to the Supreme B. and neither to insentient Prakrti nor to the Jivatrnan (Pranabhrt) which should settle the matter, especially when the Sutrakara refers to B as the one to be sought, approached and attained by the released souls! (Muktopasrpya I. 3. 2). These two sutras are sufficient to establish that the Jiva and Brahma Svarupa are entirely different and their difference persists in Moksa too. S's commentators have no doubt tried to overcome this obstacle by explaining that the Jivatrnan is excluded in the sinre Prenebbrcce not because he is not a sentient being like B. but His self knowledge in Sarnsara is conditioned and circumscribed by the limiting factor upadhi of Avidya, which is not the case with B. This comes into conflict with the strict Advaita position that B's omniscence too presupposes its being conditioned by the Upadhi of avidya - as Anandabodha has explicitly held - Sarvajnatvam api evtdyevetvem a ksipe ti, na tu pretiksipeti and does not throw it out.

S's strategical device in interpreting the Sutras is based on the principle of Adhyaropa and Apevada - First superimpose and then demolish it. But this dictum is completely falsified when we come to the concluding part of the sutras - the Journey's end which categorically debars the released souls from exercising the cosmic prerogatives of B - Jagadvyapara (IV. 4. 17). A still earlier sutra Ananyadhipatih, (IV. 4. 9) declares that the released are under the control of no other Master or Ruler over them than B., which reminds us of the RV text: Uta amrtatvasya lsanah (x. 90, 2c) - "And He is the Ruler of the immortals." Had the Sutrakara intended to rule out the existence of any Overlord over the released, he would with due regard for brevity of expression in the sutra diction, (alpaksaratvarn) have used the shorter and unambiguous Apatih (has no overlord) instead of the ambiguous ananyadhipati which S turns to his advantage of the Mukta being without a. Master or overlord - which is obviously in conflict with the wording of IV. 4. 17. To prevent this internal and mutual self contradiction, a shrewd and resourceful commentator of S puts in "Ita upari Saguna vidyaphalaprapancah", from IV. 4.8 the Sutrakara reverts to the fruit of Saquna Vidya. In that case there can be no need for S to deny any Ruler over Muktas as Saquna Mukti will not be inconsistent with there being a Ruler over Saquna Muktas and S could have left them alone.

Instead of indulging in such rigmaroles, M's bhasya tells us n two short words - Sutrarthe ucyate, giving a broad hint how, why and from whom all, he differs among earlier commentators.

The Arse Tradition of interpretation of the entire body of the Vedic corpus including the Upanisads as one single indivisible integral revelation and illumination revived by M and applied to the interpretation of the Vedic hymns, the Upanisads and the Sutras gives a long awaited corrective to the under-estimation and denigration of our ancient Vedic heritage as a crude and hopeless Polytheism of the Aryan invaders, groping in the dark thro Katheno Theism for ages, by the early Western Oriental scholars and echoed assiduously by their followers among modern Indian scholars. This should open the eyes of other traditional commentators of our scriptures as well.

The stand taken by the Rgvedic seers - Yo aevenem nemedhe eka eva (RV, X. 82.3) bringing the gods of the Pantheon, Indra, Mitra, Varuna , Agni etc. under the aegis of the one Servanamavan as the sole survivor in Mahapralaya as the ONE (tad ekam) breathing windless by its own power and named as the Jetsn in the Chan. Up. (Ill. 14. c) as brought to light by M, should now atleast open our eyes to the truth. What is noteworthy about the concept of Servanamavan is that it does not do away with the existence of the gods of the Pantheon, within their respective jurisdiction in cosmic government. This principle has been applied to the Samanvaya of Sastra in B. in their highest connodenotative application of their respective names, by M.

The swearing by the Upanisads alone as Para vidya, the Advaita school has not hesitated to exclude nearly three fourth of the Upeniseaic corpus as A- Tattva-avedaka (not truth declaring) and hence not fit to be known by seekers of Moks« - Murnuksu - ajijnasya.lt has given importance only to texts from the Upanisads which are Ostensibly in favor of Monism. Even among them, it has elevated four or five - hand-picked ones and christened them as Mahavakyas(great sentences).These have to be construed as impartite judgments in terms of a bare indeterminate pure consciousness (cinmatram) without any referents. This way of construing them has been contested by Dvaita thinkers, as innocuous and against all logical, grammatical and contextual grounds and the spirit and letter of such illustrations as have been provided in the texts themselves.

In short, a bare impartite judgement in terms of pure consciousness as cit or cinmatram, without referents would be tautological and incapable of acting as a corrective to the malady of a beginningless illusion of difference between Jiva and B. from which humanity is suffering, according to Advaita thinkers. But the fact remains that only a specific distinguishing judgment with referents (Saprakaraka jnana) can ever act as a correcting cognition against illusions. A Nisprekereks: Jnana can do no correction.

In this connection, I have raised a moot question, for the first time in the history of discussion of the Tattvam asi and other texts regarded and christened as Mahavakyasby the Advaita school alone, about the provenance of this particular designation given to them and being used as a Magic wand, to mesmerise others.

As a Research scholar, I am particularly interested in the provenance of the actual use of this designation, in the Principal upanisads, commented upon by Adi-Sankara or in his own Bhasyas on them or in his Sutrabhasya or Gita bhasya - the only three works accepted by competent modern scholars as his genuine works.

As a research scholar, I have not been able to come across any specific evidence of the provenance of the actual use of this designation or nomenclature to Tattvamasi or other texts in any of the above works which should command our attention primarily, regardless of a large number of - Sankara Apocrypha. My question is not at all concerned with the way in which Advaita interprets these texts in terms of Akhandartha (impartite judgements). That is a different matter altogether, which has to be weighed on its own merits. We should not mix up the two issues.

I am entitled to raise this question, may be for the first time. That does not make it irrelevant because no body else has done it so far. I had therefore raised this question in my work on Mahatatparya of Mahavakyas. The book was reviewed in the prestigious "Hindu" of Madras (Chennai) on 12-6-2001 by a reviewer who has signed as SR. But instead of facing the question squarely and answering it, if he can, he has simply shirked his responsibility and evaded and dodged it by irrelevant musings. I am therefore raising the question again here in the hope that some really responsible Research scholar will enlighten me with relevant texts from the sources I have named.

The study and understanding of the philosophy of the Brahmasutras as expounded by M in his BSB and AV and by Jayatirtha in his mammoth philosophical classic on the AV - the Nyayasudha have always been recognised as the highest watermark of mature Sastra scholarship, in Pandit circles. In the circumstances, it is venturesome on my part to attempt to give even an abridged English Version of their salient features and make it a readable, intelligible and useful presentation of the subject matter, to suit not only modern academic needs, expectations and requirements, but of the general readers interested in the subject, to the best of my abilities. In spite of the saying Na hi sarvadhikarikamsastram nama, I have attempted to interest and satisfy different tastes, types, orders and classes of readers. I hope my efforts to do so will be appreciated and well received by them.

This should explain the need for giving the gist of Adhi.s passed over by the AV and my parenthetical references and comments on the performance of commentators of other schools to facilitate comparative study and assessment and a reshuffling to some extent of the textual order of the Adhi.s in Adhyayas III and IV.

It is the boundless grace of my Antaryami, Acarya Madhva and of his chosen expositor Jayatirtha acting in unison which have given me the necessary physical and mental energy to take up and completed such a stupendous task at the advanced age of 93. I now humbly submit it to them, with all its shortcomings for their gracious acceptance.

His Holiness Sri Satyatma Tirtha Svamiji, the young Pontiff of the Sri Uttaradi Matha, has once again graciously come forward to have the present volume also published on behalf of Visva Madhva Mahaparisat, Bangalore, as a mark of his love of learning and affection towards me. He has placed me in a debt of deep spiritual gratitude to him. My humble and reverential pranamas at his holy feet.

A very close and sear friend of mine Sri N. S. Chakrapani (Rtd. Manager, Air India, Mumbai) of Bangalore, who has often impressed me by his remarkable insights into Madhva's philosophy, has been good enough to make a grant in aid of Rs. 20000/- towards the publication of this volume. I express my sincere thanks for his spontaneous gesture as a true Sahrdaya.

My grans daughter-in-law Sau. Asha Purandar Bhavani has once again most readily and cheerfully come forward to shoulder the responsibility of getting the Mss. of the present volume with all its difficult transliterations of Sanskrit passages, so carefully computer-typed for the Press. It is my great pleasure to record my hearty thanks to her.

My dear son Dr. Sudhindra K. Bhavani, retired Professor and Head of the Dept. of Sanskrit and Principle of K. J. Somaiya College of Arts and Commerce, Vidyavihar, Mumbai – 400077, has taken the sole responsibility of correcting and passing the proofs with his characteristic thoroughness, scholarly interest and dedication to Brahmavidya. I invoke the blessings of my Antaryami on him and his family.

| Dedication | v |

| Svamiji's Asirvacan | vii |

| Abbreviations | viii |

| Author's Preface | xii |

| Key To Diacritical Marks | xx |

| Adhyaya - II | |

| Pada 1 | |

| Introduction to Avirodhadhyaya | 1-3 |

| Smrtyadhikaranam | 3-8 |

| Na Vilaksanatva Adhi | 8-14 |

| Abhimanyadhikaranam | 14-15 |

| Asad Adhi | 15-18 |

| Bhoktrapattyadhikaranam | 19-20 |

| Arambhanadhikaranam | 20-27 |

| Itaravyapadesa Adhi. Srutestu Sabdamulatvadhi | 27-32 |

| Na Prayojanavattvadhi | 32-33 |

| Vaisamya - Nairghrnyadhi | 33-37 |

| Sarvadharmopapattyadhi | 37 |

| Pada 2 | |

| Introduction to Avirodhadhyaya | 38 |

| Racananupapatti Adhi | 28-40 |

| Anyatra - Abhava Adhi | 40-41 |

| Abhyupagamadhi | 41 |

| Vaisesika Adhi | 41-44 |

| Buddhist Schools | 44-46 |

| Jaina Adhi | 47 |

| Pasupata Adhi | 47-48 |

| Sakta Adhi | 48-51 |

| Pada 3 | |

| Introduction | 52 |

| Viyad Adhi | 53-56 |

| Matarisvadhi | 56-57 |

| Jna Adhi | 58 |

| Utkrantyadhikaranam | 58-59 |

| Prthagupadesa Adhi | 59-61 |

| Jivakartrtva Adhi | 61-62 |

| Amsa Adhi | 62-64 |

| Pada 4 | |

| Adhyaya - III | |

| Pada 1 | |

| Pada 2 | |

| Introduction to Bhaktipada | 67-69 |

| Sandhyadhikaranam & others | 69-73 |

| Na Sthanabheda Adhi | 73-75 |

| Arupadhikaranam | 75-77 |

| Upamadhikaranam | 77-80 |

| Ambuvad Adhi | 80 |

| Avyakta Adhi | 81 |

| Ahikundala Adhi | 81-83 |

| Pada 3 | |

| Introduction to Upasanapada | 84-86 |

| Sarvavedantapratyayadhi | 86-88 |

| Anandadyadhikaranam | 88-89 |

| Bhumnah Katuvad Adhi | 89-90 |

| Advaita Bhakti & Dvesa Bhakti | 90-92 |

| Aniyamadhikaranam | 92 |

| Iyad-Amananat Adhi | 92-93 |

| Na Samanya Adhi | 94-95 |

| Pada 4 | |

| Introduction to Aparoksajnanapada | 96 |

| Stutyadhikaranam | 96-97 |

| Adhyaya - IV | |

| Pada 1, 2 & 3 | |

| Introduction to Phaladhyaya | 98-101 |

| Pada 4 | |

| Introduction | 102-103 |

| Bhogapada | 103-106 |

| Doctrine of Moksa in other schools | 106-107 |

| Advaita Moksa | 108-111 |

| Appendix - I | |

| Madhva Sampradaya & Gaudiya Vaisnavism | 112-116 |

| Credentials of "Acintyabhedabhedavada | 116-120 |

| Appendix - II | |

| Post-Script tp Smrtipramanyavicara | 121-122 |

| Appendix - III | |

| Some opinions about Dr. Sharma's Works | 123-127 |

| Appendix - IV | |

| Other Published Works of the Author | 128-129 |

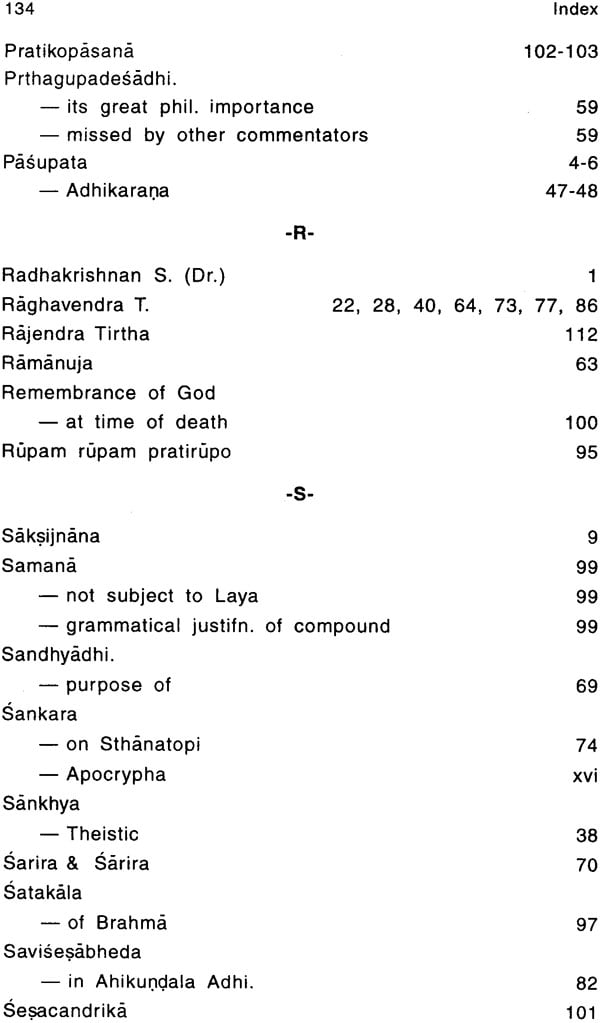

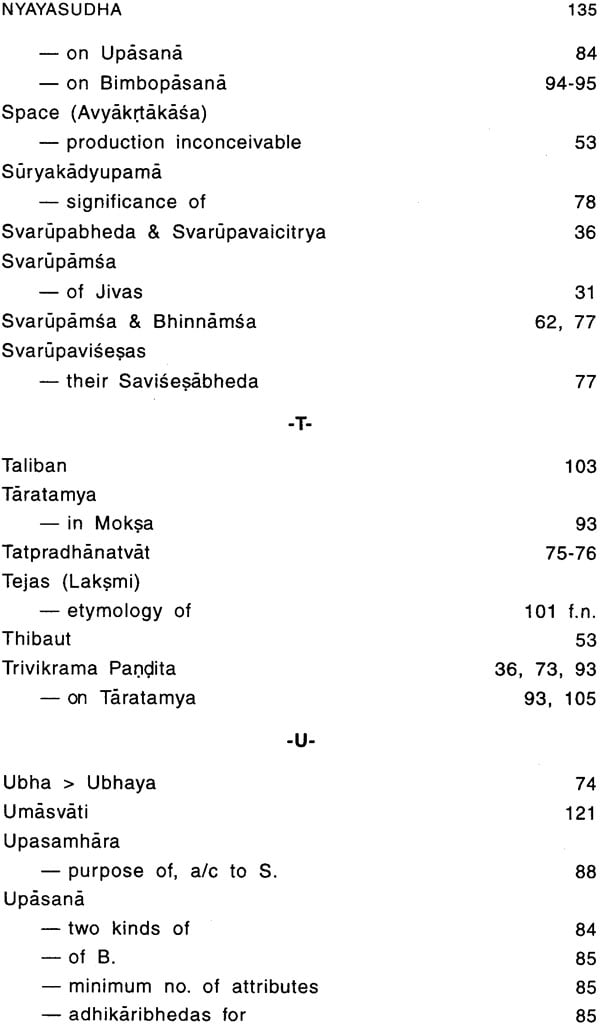

| Index | 130-136 |